Ilankai Tamil Sangam28th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Big Oil in Tiny CambodiaThe burden of new wealthby Seth Mydans, The New York Times, May 6, 2007

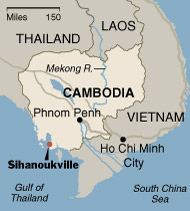

Exploratory drilling began two years ago, and the oil giant Chevron says it has found potentially huge deposits off the southern shore. The company has not made the results known, but together with other likely deposits nearby and with mineral finds being explored onshore, experts say, Cambodia could be a resource-rich nation. Top officials, including Prime Minister Hun Sen, have been feeding the excitement this year, offering extravagantly optimistic estimates that the oil money could start to flow within two to three years. But all of this is not necessarily good news. For many struggling countries, like Nigeria and Chad, oil has been a poisoned bonanza, paradoxically dragging them into deeper poverty and corruption in what some call the oil curse. “This will be a watershed event for this country one way or another,” said the American ambassador, Joseph A. Mussomeli. “Everyone knows that it will be either a tremendous blessing or a terrific curse. They are unlikely to come out unscathed.” Indeed, this is a land that already suffers many of the symptoms of the oil curse, even before a drop of oil has been pumped. With its tiny economy, weak government institutions, widespread poverty and crippling corruption, Cambodia seems as ill-suited as any country to absorb the oil wealth widely expected come its way. Its people remain traumatized by the mass killings by the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979, when 1.7 million people died, and by the decades of civil war, brutality and poverty that have followed. Now, 28 years after the ouster of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia is fitfully approaching the start of a trial of a handful of surviving leaders that could bring some belated healing. Coming together, the impending trial and the approaching flow of oil mark a transition in Cambodia from its still-raw past to a suddenly more challenging future. “I do believe this is Cambodia’s last best chance to take its place in the world and the region,” Mr. Mussomeli said. “If not, they’re going to be a basket case into the next century.” Cambodia has six potential fields in the Gulf of Thailand, more than 100 miles off Sihanoukville, as well as several other fields in areas that are disputed by Thailand. Onshore, mining companies have found deposits of a variety of minerals, primarily bauxite and gold, that could add to the country’s riches. The rush of foreign countries whose oil companies have staked claims includes China, which controls one of the six potential fields in the gulf. China has become Cambodia’s biggest commercial investor, its biggest aid donor and its hungriest consumer of raw materials, pushing ahead with major hydropower and road-building projects. In early 2005, in the first of the six Gulf of Thailand fields to be explored, Chevron said it had found oil in four out of five wells. Two more rounds of exploratory drilling have followed. A company spokeswoman, Nicole Hodgson, said in late April that those results were being analyzed and would be announced later this year. She declined to estimate the size of the field. If used wisely — as Prime Minister Hun Sen promises it will be — oil wealth could be the salvation of this country of 14 million, where 35 percent of the population lives on less than 50 cents a day. Over all, it could dwarf a small-scale economic recovery that reached 10 percent growth last year, based mostly on garment manufacturing and tourism, as well as construction and agriculture. Money from oil could help build clinics and schools and roads and irrigation canals and bring electricity to the 82 percent of Cambodians who now live without it. Or it could be sucked up by a small, powerful elite that already devours most of the wealth and bring on the symptoms of the oil curse: a breakdown in government services, economic stability and social order. “We will try our best to make sure that the oil income is a blessing, not a curse,” Mr. Hun Sen said. “These revenues will be directed to productive investment and poverty reduction.” But he has made other promises, like vowing to crack down on illegal logging and corruption, that did not seem to have been backed with muscle. Vast stands of timber and deposits of gold and precious gems have disappeared with little benefit to the people. Government buildings have been sold for profit. The tourist concession at the country’s most famous killing field has been leased to a Japanese company. Ticket fees from the national symbol, the Angkor temples, mostly go into private hands. Transparency International, a private monitoring agency based in Berlin, recently ranked Cambodia 151st out of 163 countries in its annual report on perceptions of corruption. To avoid the worst consequences of sudden wealth, it seems, Cambodia must change its ways. But the men in power may not be prepared to resist the temptations that have overwhelmed some other oil-rich nations. “If we look at the past, it’s not too good,” said Sok Hach, president of the Economic Institute of Cambodia, a private research group. “I still hope those people in charge can change. But if things don’t change, I’m really afraid Cambodia will collapse.” Looking into the future, Ian Gary, an oil and mining expert with the aid group Oxfam America, said “the nut of the problem” was something that was already the case in Cambodia: “an influx of money going straight into the hands of the central government, where there are few checks or balances.” An oil-rich government, happy at its trough and free of the need to collect taxes, may ignore its constituents. Economic disparities could lead to social unrest, political instability and violence. “The record is extremely poor,” Mr. Gary said. “We’ve seen over time that there are greater incidences of civil war and conflicts in oil-rich states, that development indicators are low, and there is often negative growth.” Even with the best of will, small economies may not be prepared to absorb the windfall, said Purnima Rajapakse, deputy head of mission in Cambodia for the Asian Development Bank. An economy centered on oil may cause other industries — like garments in Cambodia — to wither, adding to joblessness and poverty. There are signs that Cambodia may already be turning down the wrong path, some experts said. Transparency is crucial to the proper management of oil money, and the government has so far released little information. Mr. Sok Hach said he was frustrated by his inability to get more facts and figures about the oil finds for his economic analyses. “The oil will start in two or three years; it’s tomorrow,” he said, “and the government does not want to release anything."

| ||

SIHANOUKVILLE, Cambodia, April 27 — Still clawing its way out of the ruins of its brutal past, Cambodia has come face to face with an extraordinary new future: It seems to have struck oil.

SIHANOUKVILLE, Cambodia, April 27 — Still clawing its way out of the ruins of its brutal past, Cambodia has come face to face with an extraordinary new future: It seems to have struck oil.