Ilankai Tamil Sangam28th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

The Indo-LTTE War (1987-90) An Anthology, Part 12

| ||

|

What will become of the accord with India? Mr Jayewardene says it is a fixture. The limited self-rule it promised to Tamils in the form of a provincial council for the north and east is now functioning. Only the Tigers, of all the separatist fighters, remain on the loose, but they now seem weak as kittens because of the presence of the Indians. Those close to Mr Premadasa say he may replace the accord with a ‘friendship treaty’, whatever that means. He may then ask the Indians to start pulling out. This, he hopes, will keep the JVP quiet. Perhaps. But the real aim of its Marxist leaders may be to force a revolution in which it can come to power. Mr Premadasa’s promises of peace, an end to poverty, and the removal of the Indian forces without resurrecting the Tigers, will be hard to keep. Mr Jayewardene, still the ‘old fox’ at 82, will be watching attentively as he shuffles slyly to the sidelines. |

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

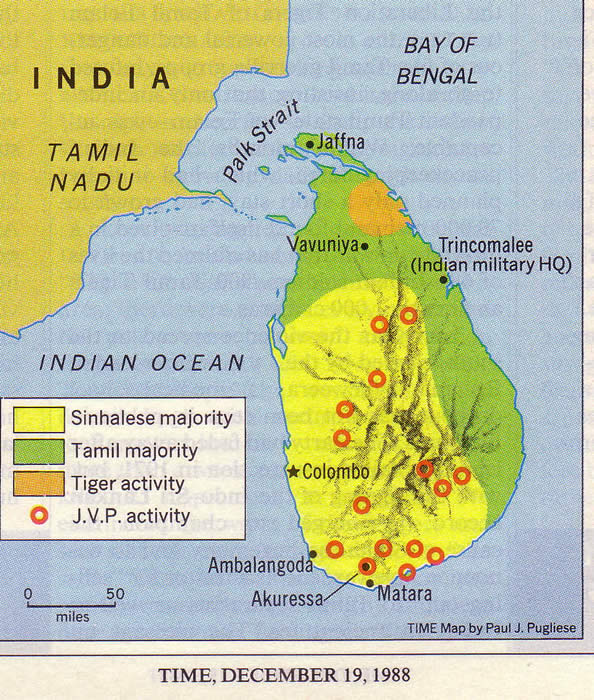

The second executive Presidential election was held on December 18, 1988. The main contenders in this election were Ranasinghe Premadasa (UNP) and Sirimavo Bandaranaike (SLFP). Notably, both pledged to the voters that if elected they would send off the Indian army from the island. The prevailing atmosphere in the island during December 1988 was distinctly different from that of October 1982, when the first executive Presidential election was held. Apart from the presence of the Indian army, other leading indicators were as follows: (1) Emergence of the LTTE in the North-East regions of the island and the JVP in the Southern regions. (2) Simultaneous eclipse of the TULF in the North-East. (3) Temporary ascent of EPRLF, the puppet regime of Indian mandarins and intelligence peddlers.

From Part 1 to Part 11 of this anthology, I have assembled cumulatively 99 newsreports and commentaries. I would assert that more than 98 percent of these publicly available materials have been either selectively or inadvertently ignored by Sri Lankan president J.R. Jayewardene’s biographers Professors K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins [vide, J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka, vol. II, Leo Cooper/Pen & Sword Books, London, 1994], to present their protagonist in a good light, and to project the LTTE as the ‘bad guys.’ Nevertheless, the documented record speaks otherwise. Presented below, for Part 12 of this anthology, are 10 news reports and commentaries that appeared in December 1988.

In variance to the previous 11 parts where I have selected materials from either weeklies (Time, Newsweek, Economist, Asiaweek, and Far Eastern Economic Review) or monthlies (South), I have included a commentary by Barbara Crossette that appeared in the New York Times of Dec.18, 1988. Note that the Time magazine issue of the same date reported that by then, “681 Indian soldiers, 900 Tamil Tigers and nearly 1,000 civilians” had died in the Indo-LTTE war. The same issue also featured short ‘box profiles’ on the thoughts/predicaments of seven Sinhala and Tamil individuals. Among these seven, two (B.Y.Tudawe and Theepan) were well recognized in the island. Tudawe was a Communist Party MP for Matara and the Deputy Minister of Education, from 1970-77. Theepan is “a Tamil Tiger field commander.”

Manik de Silva: Merged – for now. Far Eastern Economic Review, Dec.1, 1988, pp. 36-37.

Anonymous: Enter Hydra. Economist, Dec. 3, 1988, p. 28.

Anonymous: Slide Into Anarchy. Asiaweek, Dec. 16, 1988, p. 29.

Barbara Crossette: Blood, alienation and chauvinism accompany Sri Lankans to polls. New York Times, Dec. 18, 1988.

Ron Moreau: Sri Lanka’s Killing Spree – Can anyone govern? Newsweek, Dec. 19, 1988, pp. 37-38.

Lisa Beyer: Edge of the Abyss – A surge of savagery that chokes off all reason. Time, Dec. 19, 1988, pp. 28-33.

Manik de Silva: The killing Campaign. Far Eastern Economic Review, Dec. 22, 1988, p. 23.

Sri Lanka Correspondent: Democracy’s Day of Courage. Economist, Dec. 24, 1988, p. 33.

Michael S. Serrill: Patching an Old Feud. Time, Dec. 26, 1988, p. 23.

Anonymous: Breakout – An explosive prison escape. Time, Dec. 26, 1988, p. 24.

Merged – For Now

[Manik de Silva, Far Eastern Economic Review, Dec.1, 1988, pp. 36-37.]

Sri Lanka’s major obligation under its 1987 accord with India was completed on 19 November with a council election for the temporarily merged Northern and Eastern provinces where Tamil separatists have been fighting a five-year long war. Yet, despite a surprisingly high 63% voter turnout, the credibility of the new council remains in question because the dominant guerilla group refused to contest the election.

Also in question is the permanence of the merger. The Eastern Province is populated in almost equal proportion by Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims, and a referendum must be held there within a year to determine whether the people wish to remain linked – and therefore dominated – by the predominantly Tamil north.

Whether the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) refusing to contest because they opposed the accord itself, the 36 northern seats went uncontested to an alliance of the relatively less influential Eelam People’s Revolutionary Front (EPRLF) and the Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front. The EPRLF also contested seats in the east against the two year-old Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, and the ruling United National Party (UNP).

Predictably, the EPRLF, which was backed by India, and the Muslim Congress carried the province, with 17 seats each, with the UNP winning a solitary seat. It was clear that Muslims had voted for the congress and the Tamils for the EPRLF. The Sinhalese, resentful of the merger and unhappy about the lack of protection from attacks by the Tamil separatists, appeared to have largely ignored the election.

As both the LTTE and the militant Sinhalese Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in the east had tried to frighten voters away from the polls, the 50,000-strong Indian Peace Keeping Force, in Sri Lanka for 15 months now to help implement the 1987 accord, worked hard to ensure minimum disruption. The Indians stressed that the election was conducted entirely by the Colombo government with their troops only providing security and, where requested, some logistical assistance.

With the presidential election due on 10 December and the majority of the non-Tamils in the Eastern Province perceived to be opposed to a continuing north-east link, many observers in Colombo expect President Junius Jayewardene, who is not seeking re-election, to quickly announce a date for the referendum in the east. The Indians who perceive Tamil aspirations as strongly pro-merger would not favor any delinking. Questions are already being asked about whether the Indians would cooperate in holding a referendum in which their interests might lose out.

The Muslim Congress, with its strong showing in the east and its less spectacular successes in winning Muslim votes in earlier provincial council elections elsewhere, is preparing to use its leverage with both the UNP and the main opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) to carve out a Muslim majority provincial council in the east, for it does not favour a merger either. The congress has thus far backed the SLFP’s presidential candidate, Sirima Bandaranaike, but may now offer its support to whoever it can wrest concessions from in the parliamentary election that mus follow the presidential poll.

While Bandaranaike is already committed to doing away with the provincial councils, which were only set up this year, should she win the election, it is clear that the SLFP is willing to concede considerable provincial autonomy to Tamil- and Muslim- majority areas to resolve the ethnic strife that has torn Sri Lanka society and its economy apart. Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, the UNP presidential candidate, has slowly distanced himself from Jayewardene’s arrangements with India – under which the provincial councils were to be formed – and both he and Bandaranaike tell election rallies that if elected they will secure an Indian pull-out. But with the Indians having failed so far to disarm the LTTE, and Sinhalese militants creating havoc in the south, an immediate Indian withdrawal would hardly be practicable.

Any Colombo government has to also be conscious of the fact that the Tamil separatist war was able to assume the proportions it did because of the Indian factor in the equation. The Tamil separatists enjoyed extensive support from the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu and both trained and staged raids from there until the 1987 accord, when New Delhi deprive them of logistical and other support. A future Sri Lankan Government proposing to tinker with the accord cannot be unconscious of the inherent dangers of such an action.

While the northeast election was being concluded, the southern militants continued their rampage in the majority Sinhalese areas. A spate of selective killings disrupted public transport in many areas with bus and train operators refusing to work for fear of attack. Electrical sub-stations and power lines were sabotaged causing extensive blackouts in some parts of the country and troops had to be deployed to ensure essential services continued and to bring frightened employees to work.

*****

Enter Hydra

[Anonymous, Economist, Dec.3, 1988, p. 28.]

Surely there must be something to report about Sri Lanka that is not wholly gloomy? Well, there’s the tea crop. It is unusually good this year. Unfortunately, much of it is likely to stay on the plantations. The roads from the tea-growing areas to the capital, Colombo, where the tea would be auctioned, packed and exported, are unsafe. Some gets through, escorted by soldiers, but a lot of it will never reach the teapot.

The tea is a metaphor for all of Sri Lanka, a country with an abundance of good things to offer the world, cash crops, precious stones, textiles, free-trade zones and tourism, but all of them stymied by a civil war that is getting more terrible each day. It is now taking on the character of Hydra, the monster of Greek mythology that grew two heads when one was cut off.

Sri Lanka’s only monster used to be the Tamil Tigers, who have been fighting tooth and claw for a separate state for the minority Tamils in the north-east of the country. Sri Lanka has not quite cut off the Tigers’ head, but it has shooed them into the jungle with the aid of soldiers from India. But by bringing in the Indians, and be offering political concessions to the Tamils, it has created a second monster.

The People’s Liberation Front, generally known by the initials JVP (for its Sinhalese name, Janata Vimukthi Peramuna), claims to speak for the island’s Sinhalese majority. It is bitterly opposed to the provincial autonomy offered to the Tamils of the north-east, and to the presence of 50,000 Indian soldiers in Sri Lanka, who came in as part of a deal designed to bring peace to the Tamil areas. The Front has declared war on the government of President Junius Jayewardene for doing this deal, which, it says, has put Sri Lanka under India’s thumb.

Like the Tigers, the Front has a philosophy which is unlovely and implausible mixture of Marxism and racism. Its aim is to disrupt the country so much that the government will collapse. It has frightened the drivers of the tea lorries and destroyed the tourist trade. The Front is as brutal as the Tigers. Since the government signed the pact with India in July 1987 it is believed to have killed more than 600 people, mostly government supporters. In a 24-hour period this week it shot dead 15 people. In the rural areas of southern Sri Lanka, where most Sinhalese live, its word has become law. It forbids people to go to work; so there is no public transport, shops run out of supplies, hospitals have no medicine and there is a shortage of cash because banks do not open.

The JVP’s target now is Colombo. Its posters went up in the capital this week decreeing that all activity should stop on December 5th. From that day even private cares will not be tolerated on the streets. The order will remain in force until December 19th, when a presidential election is due to be held. It seems the Front plans to make that election impossible.

It looks fairly impossible anyway. Were the country not near anarchy it would be a straightforward choice between Mr Ranasinghe Premadasa, the candidate of the ruling United National Party, and Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the candidate of the main opposition group. After 11 years of United National Party government under Mr Jayewardene (who is retiring), Mrs Bandaranaike would probably win. She is a former prime minister and has the right background; all but one of Sri Lanka’s governments during the 40 years since independence have been headed by someone from one of the great political families, the Senanayakes and the Bandaranaikes. She is of high caste (as important to Buddhist Sinhalese as it is to Hindu Tamils), while Mr Premadasa is of low caste.

Such rationalities no longer seems to matter as much as they did even a couple of months ago. Mrs Bandaranaike has hinted that she might pull out. She suspects that the government may be fixing the election. In Colombo suspicious opposition people mutter that 1.2m illegal voting slips have been prepared to stuff the ballot boxes. The story is a symptom of the malaise in Sri Lanka, a once rather decent country where previous elections have been mostly fair. Mr Jayewardene sought to counter the rumour this week by agreeing that foreign observers could monitor the election.

Or Mr Jayewardene may call off the election, believing that it will end in chaos (even though the soothsayers claim it will be auspicious for Mr Premadasa). He would then continue as executive president, perhaps calling a parliamentary election, a popular move as there has not been one since 1977.

Assuming the presidential election goes ahead, the winner, whether Mr Premadasa or Mrs Bandaranaike, will come to office on a promise to scrap the deal with India. Not only would the Indian soldiers be asked to go home, removing from Sri Lanka its most disciplined group on the side of law and order, but one of Mr Jayewardene’s greatest achievements would be endangered. This was the highly successful election in November of a Tamil-run provincial council for the island’s northern and eastern districts. Voters turned out in great numbers, despite a demand from the Tigers for a boycott. The council, which once seemed a hopeless dream, has now appointed a terrorist-turned-democrat as provincial minister. If the council collapsed, any hope of peace for the north-east would be over.

These are agonizing times for the 82 year-old Mr Jayewardene. He acted courageously in bringing in the Indians and pressing ahead with some kind of Tamil self-government. The army is stretched to run even essential services, but Mr Jayewardene has declined to impose martial law. He may not despair, but he finds it difficult to know what else he can do to hold his little country together. Getting rid of Hydra took all the strength and guile of Hercules.

*****

Slide Into Anarchy

[Anonymous; Asiaweek, Dec. 16, 1988, p. 29]

Once a familiar figure, the postman in Sri Lanka’s Southern Province has been replaced by a stranger with a mail-bag in one hand and an automatic rifle in the other. The postal service is one of the many institutions taken over by the army as the country continues its slide into anarchy. According to the latest official figures, 439 people were killed in a 30-day period recently, most of them by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front). The JVP has vowed to bring the government to its knees.

Civil administration in 20 of the island’s 26 districts has been crippled as thousands of frightened administrators and clerks obeyed the terrorists’ call for a nationwide boycott. More than 200 senior government officials in the Southern Province were taken into ‘protective custody’ by the army. ‘They are essential to keep the services running,’ explains Col. Vipul Boteju, coordinating officer in the Hambantota district. ‘We had no alternative but to force them to work.’ Ex-soldiers and officers are being recruited to meet mounting manpower needs. Army technicians are being trained to take over computer systems in major banks and the international airport. Others are being taught to run the petroleum refinery, overseas telecommunications, power stations and the television and radio networks.

Troops battling the insurgents have been given wide emergency powers. ‘If we didn’t strengthen units in the south, the country would be in chaos,’ National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali told Asiaweek. President Junius Jayewardene has appointed Maj.-Gen. Cecil Waidyaratne as head of the First Division in charge of the all-out offensive. The division includes officers who planned the May 1987 invasion of the northern Jaffna peninsula held by Tamil separatists. Officers say troops have overcome qualms about fighting fellow Sinhalese. But according to another army source, overzealous soldiers are repeating mistakes made in fighting the Tamils. He says recruits from the south, sickened by what they see as indiscriminate slaughter, are in a mutinous mood.

The opposition has urged Jayewardene to hand over power to a caretaker government before the Dec.19 presidential elections to defuse the crisis. Instead, he has promised to dissolve Parliament on Dec.20 and bring forward the general elections by six months to Feb.15. ‘An opportunity should be given to the people to elect a new parliament so that the new president will have the benefit of the views of the electorate,’ Jayewardene explained.

The move is unlikely to assuage the JVP, which is disrupting presidential campaigns with bomb attacks. Among the latest victims were Devabandara Senaratne, vice-president of the opposition Sri Lanka People’s Party, and two supporters. Tourists and expatriates are fleeing the country in the countdown to the polls. The government has vowed not to let up on its military campaign. Declares a senior cabinet minister: ‘Even if [the media]stand on their heads and shout about human rights, we’ll go ahead. If not, there will never be peace in this country.’

*****

Blood, Alienation and Chauvinism Accompany Sri Lankans to Polls

[Barbara Crossette; New York Times, Dec.18, 1988.]

Dharshanie is only 22. Her brother is a soldier. But that does not dampen the fire in her that turned her against one of Asia's oldest and most resilient democracies. ''At the moment, I don't think that democracy exists in this country,'' she said as she settled down with two fellow Sri Lankan students to explain what has brought them to the brink of violence, even revolution. ''Look at the adult generation we have,'' she says. ''They are calling it a democracy and shooting schoolchildren. This is the kind of government our parents have put in power to protect us.'' Opposition Grows Rapidly

Darshanie, a Colombo University student, and her colleagues, Kumar and Gamini, are part of a rapidly growing phenomenon deeply troubling to Sri Lankans of almost every political persuasion: the drift of the country's ethnic Sinhalese youth, children of the majority, into a violent opposition coalescing around a shadowy group called the People's Liberation Front and the more ruthless, armed Patriotic People's Movement.

With a presidential election scheduled Monday, the movement this weekend has threatened to shut down Sri Lankan cities and towns with a campaign of terror and to cut off the hand of anyone who votes. A bus was set on fire in the center of Colombo today and a gasoline bomb was thrown at a shop. No one asserted responsibility for the incidents, but it was widely assumed here to be the work of Sinhalese extremists. To counter this threat, the Government of President J. R. Jayewardene, which held its last Cabinet meeting today, is planning to impose a nationwide, round-the-clock curfew after the voting Monday, a senior official said tonight.

The curfew is expected to be in effect for at least 36 hours while the votes are counted and the next President is sworn in. Posters went up in some Colombo neighborhoods today ordering citizens to stay home from midnight tonight until Monday night. Voters run the risk of being shot, as they were in provincial elections earlier this year. Troops and militias equivalent to a national guard have been sent to populated places all over Sri Lanka to try to provide security for voters.

Three candidates are running for president: Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa of the ruling United National Party; Sirimavo Bandaranaike of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, a former prime minister, and Ossie Abeygoonasekera of the United Socialist Alliance, a group of left-wing parties. The leading contenders are Mrs. Bandaranaike and Mr. Premadasa.

The People's Liberation Front contends that the Government in Colombo gave too many concessions to the Tamil minority in a July 1987 peace agreement aimed at ending the five-year insurrection by Tamil guerrillas in the north and east. Tamils make up about 18 percent of the population. In 1983, Tamil rebels launched their violent campaign for greater autonomy from the Sinhalese-dominated Government. Sri Lanka's radical students call themselves Marxists. But this is a new Marxism, said Kumar, who belongs to the student wing of the People's Liberation Front. Their movement, whose hero is Lenin, is nevertheless anti-Soviet and anti-Chinese, the students said, adding that of the Communist countries, only Cuba and Vietnam help them. Maoist and Perhaps Fascist

Many Sri Lankans describe the People's Liberation Front, led by a former Maoist, Rohana Wijeweera, as neo-fascist. For many, the militant chauvinism enshrined in the mottos of the front - ''First Motherland, Then Education'' and ''First Motherland, Then Work'' - poses a far greater danger to Sri Lankan unity and development than the Tamil rebellions.

Many Sri Lankans believe that the Sinhalese-first movements formed by some Buddhist monks and Roman Catholic priests as well as those of the university students have been coopted by the more dangerous and ruthless political tacticians of the People's Liberation Front. The students reject this. Their politicization began, they say, on education issues, like opposition to private higher education and a change in examination procedures, and mushroomed after Indian troops arrived in Sri Lanka last year under an agreement between the two countries aimed at ending the Tamil insurretion. When Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi came to Colombo to sign the accord, Darshanie said, ''I wondered why the honor guards didn't spit in his face.'' A young sailor did hit the Indian Prime Minister with his rifle.

Loss of Nationhood Alleged : To many Sinhalese, most of whom are Buddhist while most Tamils are Hindu, the country has lost its sovereignty to Hindu New Delhi. Paradoxically, many Tamils now battling Indian forces share this view. ''We are anti-Government,'' Dharshanie said. ''We are anti-accord. We are anti-Indian. If the J.V.P. has the same attitude, we can't help that,'' she said, referring to the People's Liberation Front by its initials in Sinhalese. Older Marxists are among those most disturbed by the emergence of this new left. The students accuse traditional Communists of reporting regularly and falsely to Moscow about their activities. ''There is a phenomenon here that we have not fully studied: the phenomenon of Pol Potism,'' Pieter Keuneman, leader of the Sri Lankan Communist Party, said in an interview Friday. Pol Pot was the Communist leader of Cambodia from 1975-79. He is blamed for the deaths of more than a million Cambodians. ''This Pol Potism came out of Maoism, the Red Guard movement and so on,'' Mr. Keuneman said, adding that what is happening in Sri Lanka ''is not on a massive scale like in Cambodia.'' ''But,'' he said, ''it's the same thing: young people who don't know very much, who enjoy power, who enjoy dressing up and playing soldiers.''

Escaped Death Himself: Mr. Keuneman said that assassins of the new left killed 185 Sri Lankan Communists in the last year. Two days before the interview in his small office here, Mr. Keuneman escaped an attack by gunmen. In some cases, the assaults by the Patriotic People's Movement have been carried out with extreme brutality. ''If there's a chap you don't like,'' he said, ''you go around and kill him. You kill his children. You chop their heads off. I would call it savage, but the savages are much more civilized.''

Mr. Abeygoonasekera, a presidential candidate being fielded by a coaltion of leftist parties including the Communists, has survived three grenade attacks in the last few weeks. By the end of the campign on Friday night, he was more or less in hiding. To combat rising Sinhalese terrorism, which includes the intimidation of shopkeepers and public service employees, the Sri Lankan Army and its paramilitary support groups last month were given wide powers that critics label ''state terrorism.'' These powers include the right of police officers above a certain rank to dispose of bodies without post-mortem examinations.

Students have compiled files on murders they say have been committed over the last month by security forces or vigilantes. They bring the case studies, illustrated by photographs of mutliated bodies, to foreign reporters, asking for help in publicizing their cause abroad. Asked about the reported atrocities of the Patriotic People's Movement, the students say that someone had to take up arms ''to protect the people'' from the Government and from the Indian troops.

*****

Sri Lanka’s Killing Spree – Can Anyone Govern?

[Ron Moreau, Newsweek, Dec.19, 1988, pp. 37-38.]

On a grassy hill overlooking a stream where white egrets wade, a pile of human bones lies smoldering in a heap of ashes. Villagers say that Sri Lankan soldiers dumped four bodies one night and set them ablaze in this spot near the town of Kaduwela, just east of Colombo. They say the victims were probably suspected members of the Sinhalese revolutionary group, the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), who were picked up by the military in one of its nightly house-to-house searches – and then executed. ‘Why did the Army kill rather than jail them?’ asked one young man. ‘I think it’s a warning not to cooperate with the JVP’, a friend answered.

Terror is nothing new to the Indian Ocean island of Sri Lanka, where the struggle between ethnic Sinhalese and Tamils has claimed thousands of lives since battles erupted in 1983. But with each passing month the nation’s mightmare deepens as the once sporadic violence becomes common place and any semblance of law and order evaporates. The JVP, which bitterly opposes the Indo-Sri Lankan peace accord intended to grant limited self-rule to the Tamil minority, has killed more than 600 government and treaty supporters since the pact was signed in July 1987. Recently it has turned its guns on opposition politicians in a savage attempt to disrupt the upcoming presidential election.

Outgoing President Junius R. Jayewardene has counterattacked with a vengeance, imposing draconian emergency regulations and unleashing his 40,000 – man security force – bolstered by shadowy paramilitary groups known as ‘Green Tigers’, who terrorize government opponents. In the northern provinces where the Tamils are in the majority, uncompromising Tamil guerrillas of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) separatist organization continue to battle 60,000 Indian peacekeeping troops sent in under the terms of last year’s treaty. The resulting islandwide slaughter is claiming more than 20 victims every day. ‘People are scared to death,’ says one Western diplomat in Colombo, ‘and the government is fighting for its life.’

Early last month the JVP dramatically escalated its war against Jayewardene. Through death threats spread by letters, posters, word of mouth – and by selective political murders – JVP rebels have cast a pall over life in southern Sri Lanka. JVP-ordered hartals (strikes) closed schools, government offices, private shops, markets, banks and gas stations and brought bus, train and truck service to a halt. Plantations that supply export-earning tea, rubber and coconut have ceased production, and food shortages have become commonplace. Many civil servants, bus drivers, truckers, dock workers and plantation owners who didn’t comply with the warnings to stop work were killed. The extremists beheaded student leaders and policemen who refused to cooperate and even exhumed and beheaded the corpses of victims if families didn’t follow humiliating funeral rites prescribed by the JVP.

The strikes and mindless violence have disrupted the lives of more than half of Sri Lanka’s 16 million people. Hardest hit is the island’s Sinhalese deep south. There, hundreds of disaffected, unemployed youngsters who have migrated from the countryside to dead-end urban lives have drifted to the JVP. The hartals destroyed the southern coast’s lucrative tourist industry, forcing the government to evacuate some 5,000 European tourists and to cancel at least 18 charter flights due in over the winter tourist season. But the rebels seem unmoved and refuse to end their reign of terror unless the peace accord is scrapped; Indian troops are sent home; Sri Lanka’s Parliament, provincial and local assemblies are dissolved, and the presidential election is postponed until the JVP is ready to participate.

24-hour curfews: Clearly unwilling to meet any of those demands, Jayewardene sent in the Army last month with orders to shoot any demonstrators or curfew violators. While the security forces quickly restored the capital of Colombo to a rough equivalent of normality, bringing law and order to southern towns and villages where the JVP is entrenched was more difficult. But the government’s forces did have some success. The Army and police killed dozens of pro-JVP demonstrators and perhaps hundreds of suspected JVP guerrillas. House-to-house sweeps during 24-hour curfews have resulted in the arrest of more than 1,000 JVP suspects.

The Army and its loyal paramilitary groups are indulging in their own brand of terror. In the tiny southern village of Ampitiya, journalists last week ran across the bodies of three teenage boys who had been taken from their homes. Each had been shot in the head. Sri Lankan human-rights activists also report an alarming number of missing persons among JVP suspects who are believed to have been detained in the security forces’ sweeps. Some, like those found near Kaduwela, are thought to have been executed and their bodies quickly burned or buried to prevent identification.

Unfortunately, neither of the two main presidential candidates – Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasaof the ruling United National Party (UNP) or former socialist prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) – is publicly addressing the country’s deep-rooted problems. Premadasa, who has taken over Jayewardene’s UNP’s powerful urban political machine, has tried without success to blame Bandaranaike for the violence and is promising Sri Lanka’s legions of poor the equivalent of $83 a month in welfare payments – something the nearly bankrupt government can ill afford. And while saying that he opposes the Indo-Sri Lankan peace treaty, he has spoken only vaguely of a ‘phased and orderly’ Indian troop withdrawal. Bandaranaike, 72, is slowing down but still manages to draw large, enthusiastic crowds. She blames the government for the breakdown in law and order, vows to cut food prices and to write off the debt owed by poor farmers. She also promises to scrap the Indo-Sri Lankan accord and send Indian forces home.

‘Fascist beasts’: Neither candidate dares mention what should be the campaign’s major issue: how to deal with the JVP. ‘Both major candidates are trying to appease the JVP,’ says a Western diplomat. ‘They wrongly think they can co-opt it.’ Only the third presidential candidate leftist Ossie Abeygunasekera, has shown the courage to publicly denounce the JVP extremists, whom he has called ‘fascist beasts’. For his candor, JVP gunmen attacked one of his election rallies two weeks ago with machine guns and grenades, killing his deputy and several supporters.

In the end, the JVP’s terror tactics probably won’t stop the election – but they may help to decide the winner. While most Sri Lankan political analysts predict that public sentiment favors Bandaranaike – if only out of frustration with the UNP – her traditional strongholds are those very areas of the south now dominated by the JVP. If the JVP succeeds in forcing large numbers of voters to stay home there, Premadasa could win since his UNP machine is likely to get out the vote in the cities.

But no matter who wins, the next president must somehow face up to the JVP challenge. And with neither candidate voicing a coherent political and economic program to combat the causes of JVP extremism, there’s little room for optimism. ‘No one is proposing solutions,’ says one pessimistic Western diplomat in Colombo. ‘I’m afraid that no matter who wins, the prospects are not bright for Sri Lanka.’

*****

Edge of the Abyss: A surge of savagery that chokes off all reason

[Lisa Beyer, Time, Dec.19, 1988, pp. 28-33.]

[Note by Sachi: This feature contained short ‘box profiles’ on the thoughts/predicaments of seven Sinhala and Tamil individuals. Among these seven, two (B.Y.Tudawe and Theepan) are well recognized in the island. Tudawe was a Communist Party MP for Matara and the Deputy Minister of Education, from 1970-77. Theepan is “a Tamil Tiger field commander.” These ‘box profiles’ are provided at the end of the main text.]

In most of the country, one would hardly have known that Sri Lanka was nearing the end of its first presidential election campaign in six years. One morning in Ambalangoda, a coastal town south of the capital of Colombo, the presidential candidate of the ruling United National Party (UNP), Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, was just about to arrive, yet there were no crowds to greet him, no supporters waving party banners. The streets were practically deserted, and all the stores closed.

The reason was plain, unadulterated fear. The militant People’s Liberation Front (JVP), which opposes the government of President J.R. Jayewardene, had ordered a ‘curfew’, an edict Sri Lankans have learned to take seriously ever since the JVP launched a terror campaign against the regime, killing anyone who defied their writ. Security forces in Ambalangoda, however, had their orders: open up the town. Soldiers and policemen moved up and down the streets, using the butts of their rifles to smash locks off shuttered storefronts and arguing with residents to persuade them to come out of hiding. Cowering in his shop on a side street, one storekeeper was close to hysteria. ‘The army says open, the other side says close. I am in the middle. I can’t think, I can’t even speak I am so afraid,’ he whispered. ‘Please don’t mention my name or this shop,’ he added. ‘I’ll be a dead man if you do.’

There are plenty of dead men – as well as women – in Sri Lanka to prove the point. The island country, once South Asia’s success story, has been carried on a bloody tide to the edge of disintegration. More than 10,000 have perished since the first violent confrontations five years ago between majority Sinhalese and minority Tamils, who demand greater autonomy in the north and east, areas where they predominate. Since then, the conflict has spread, pitting not only Tamils against Sinhalese but rivals in each group against one another. The Sinhalese-chauvinist JVP, which describes itself as Marxist-Leninist, opposes recent concessions to the Tamils and bitterly resents the presence of Indiean peacekeeping troops, who since last year have been helping to suppress antigovernment Tamil guerrillas. JVP gunmen have wantonly contributed to the bloodletting by killing at elast 600 UNP supporters plus uncounted others, and are gaining momentum. In the south, where the JVP is strongest, more than a dozen people are killed every day in the deadly give-and-take. Having spurned invitations by the government and the parliamentary opposition to join the democratic process, the JVP poses a serious threat to the success of the presidential election on Dec. 19, as well as of parliamentary balloting promised for mid-February.

The savagery, on all sides, has reached the point where it chokes off all reason. ‘The JVP, who say they want to save us, are killing us,’ says a Sinhalese tea-plantation owner in Galle. Indian troops release a young Tamil so badly beaten and tortured that he remains hospitalized a week later; he has been forced to sign a statement saying, ‘I was not ill-treated during my stay.’ Families of JVP victims are forbidden by the killers to acknowledge the deaths with any of the traditional signs of mourning, not even a funeral procession. In Colombo the JVP orders public-sector workers to stay home from their jobs, with the result, perhaps symbolic, that 500 inmates escape from the Angoda Mental Hospital.

Still another chapter in the slaughter has opened up in recent weeks: counterguerrilla vigilantism. In the Sinhalese-dominated south, the JVP itself has become the target not only of the security forces but also of death squads that operate with the government’s unacknowledged support. In Tamil territory, the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), invigorated by its victory in provincial elections, has linked up with Indian troops to murder and terrorize Tamil rivals. Violence has become so endemic through much of the country that when passersby see a corpse along the roadside – no uncommon sight these days – they merely stop to check whether it is someone they know, then move on. ‘We are becoming another Lebanon or another Cyprus,’ says Ronnie de Mel, who resigned as Finance Minister earlier this year to join the opposition. ‘We are in a state of anarchy.’

The economy lies devastated. From 1977 to 1983, Sri Lanka’s growth rate averaged 6%: by last year it had slid to 1.5%. Inflation is estimated at 15%, unemployment at 20%. Foreign investors, once drawn to the country’s prospering free-trade zones, are having second thoughts. Electricity is out in much of the south, and train service was cut off throughout the country last week. Most universities have been all but shut for two years. In the north, Tamil newspapers report that more than two-thirds of their advertising revenue comes from death notices or from travel agencies offering to arrange emigration.

In such a climate, an election campaign seems out of place, perhaps even irrelevant. In Colombo campaigning is fairly calm by normal standards, but in the south, UNP officials are transported to rallies by helicopter and are constantly surrounded by guards. Few Sri Lankans risk being seen at political rallies, which have been declared off-limits by the JVP. In the town of Akuressa, a JVP stronghold, barely two dozen people showed up for an appearance by Premadasa.

Since September, an opposition coalition led by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party has not campaigned in the south at all because, unlike the incumbent party, it does not have the military’s full protection. The SLFP’s presidential candidate, former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, is further frustrated because all her organizers in the south fled after talks with the JVP broke down last month and the JVP declared the party ‘banned’. The Sri Lanka People’s Party, a weak third contender, has been hit even harder: early this year its leader, Vijaya Kumaranatunge, was murdered by the JVP. Two weeks ago, at a rally in Colombo, automatic-weapons fire and hand grenades downed three more SLMP supporters but missed the party’s new leader, Ossie Abeygoonasekera.

Such is the tumult surrounding the campaign that in the run-up to polling day, politicians are wondering aloud whether the turnout will be large enough to give the election legitimacy. Having declared the balloting unacceptable, the JVP is expected to order a boycott. When the organization did that in local elections in the Southern Province last spring, only 27% of those eligible turned out to vote. Many analysts suspect that Jayewardene or his successor may use the security system as a pretext for scrubbing the February parliamentary elections.

The contrast with the last presidential election, when the country was still at peace and something of a model for developing democracies, could not be sharper. ‘I remember in the 1982 presidential campaign driving myself and never thinking about security,’ says Education Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. ‘Today I can’t move without a car in front, loaded with security men, and a car behind.’ Five years ago, discontent among the predominantly Hindu Tamils, who make up 12% of Sri Lanka’s population of 16 million, over discrimination by the mainly Buddhist Sinhalese erupted into violence when Tamil guerrillas attacked an army patrol and killed 13 soldiers. Nationwide riots resulted, and enraged Sinhalese massacred as many as 2,000 Tamils.

India, home to 55 million Tamils who support their cousins in Sri Lanka, was outraged. Indira Gandhi, then Prime Minister, ordered her intelligence organization, the Research and Analysis Wing, to intensify the training and arming of Sri Lankan Tamils in India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu. Ever greater violence soon became the order of the day.

A peace accord signed last year by Jayewardene and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi offered hope of a solution, but only briefly. Under the agreement, Jayewardene promised Tamils a measure of local rule for the Northern and Eastern provinces while Gandhi dispatched troops to keep peace and disarm the Tamil guerrillas. New Delhi miscalculated: Velupillai Prabakaran, the leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the most powerful and dangerous of five Tamil guerrilla groups, refused to go along, insisting that only an independent Tamil state – or Eelam – was acceptable. Within months, the Indian peacekeeping force, which had initially planned only a short stay, had grown to 70,000 men and found itself involved in a hit-and-run war that has claimed the lives of 681 Indian soldiers, 900 Tamil Tigers and nearly 1,000 civilians.

Last year the violence spread to the south, carried by the JVP, whose leader, Rohana Wijeweera, a medical-school dropout, has not been seen in public in five years. The party had faded away after leading a failed insurrection in 1971, but, with the signing of the Indo-Sri Lankan accord, re-emerged to champion the cause of Sinhalese hegemony and to denounce Jayewardene as a traitor for ‘selling out’ to Tamil separatists as well as India, an ancient foe. The message hit home particularly in the south, where Sinhalese chauvinism and distrust of New Delhi run deep and where thousands of educated but unemployed young people are receptive to the party’s Marxist appeal. In some southern areas, 6 out of 10 young men are thought to be JVP supporters.

The JVP has grown so quickly that in recent months practically the entire 33,000-man Sri Lankan army, including 9,000 of the 12,000 men normally stationed in the north, has been deployed to the central west and south to help contain the virulent guerrillas. The effort has not gone well. Sympathy or fear makes much of the rural south JVP country. The price of disloyalty is still high: in the small village of Thihagoda, the bodies of a woman and her adult son – deemed government sympathizers by the JVP – were found in their homes, their heads smashed by hammer blows.

The JVP makes life miserable in other ways as well. Last month it tried to put pressure on the Jayewardene government by calling a general strike. In most Sinhalese areas, the stoppage lasted only a few days, but in the south it continued to sputter along as late as last week, trapping workers in a dangerous dilemma. The JVP has warned bus drivers, for example, not to do their job, and killed several of them to underline the point. Government orders, on the other hand, require the drivers to work, and soldiers have forcibly escorted many behind the wheel. Still, few buses, the main means of transportation, are on the roads.

Strikes in ports and a shortage of fuel have led to transportation problems that in the past month have nearly doubled the price of a pound of rice, to about 30 cents. In the south most government offices, including the courts, either are shut down or have ceased to operate effectively. Says a community leader in Matara, a major town in the south: ‘The ordinary man is pushed by terrorists one way, the government the other. We are fed up with both sides but also at their mercy.’

Some southerners are striking back. One morning in Matara, the bodies of two men apparently linked to the JVP were discovered on the streets with signs reading THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS TO SO-CALLED REVOLUTIONARIES. Local citizens say that only a group working with the government’s connivance could have broken the nighttime curfew to dump the bodies. Corpses marked with similar signs have begun to show up daily throughout the south.

Local strongmen aligned with the UNP are behind some of the killings. ‘The JVP was about to take over this area; there were attacks every night, and the police were helpless,’ a plantation owner in the south told TIME last week. To protect himself, he ‘worked out an understanding’ with security forces and took matters into his own hands. In little more than a week, men employed by him killed 25 suspected JVP members. ‘We eliminated the worst of the buggers and sent a shock wave through the JVP,’ he said. ‘They know that we are on the hunt.’ Ironically, some wealthy Sinhalese have hired former Tamil guerrillas to lead their private death squads. ‘They know what they are doing,’ says a satisfied customer.

The government denies any connection with vigilantism, but does admit to using other methods of intimidation, such as rounding up hundreds of young men for interrogation, then holding htem in indefinite detention: according to official figures, 4,000 are currently in custody. Colombo has granted police and soldiers emergency powers, allowing them to shoot demonstrators and burn bodies without an inquest, and is pushing a controversial bill that would protect security-force members against prosecution stemming from ‘antiterrorist’ acts. JVP activists say the killings and security sweeps have impaired their operations but have not stopped them.

In the north and east, Indian and Sri Lankan forces have had greater success against another foe, the Tamil Tigers (LTTE). Since the Indian army went into action, the number of LTTE fighters has declined from an estimated 3,000 to about 1,000. With their former training and logistics bases in southern India closed by New Delhi, the Tigers are finding it much more difficult to move arms into Sri Lanka. How much they have been weakened was demonstrated by their failure to disrupt elections in November for the new Northeastern province council, an institution created under the Indo-Sri Lankan accord to give Tamils more autonomy. Although the Tigers threatened to kill anyone who dared to vote, some 60% of those eligible cast ballots.

Both Colombo and New Delhi are well aware that they must eventually deal with the Tigers on a political level. A lawyer whose father-in-law was killed by the Tigers acknowledges that ‘any settlement that excludes the LTTE will not bring peace.’ But no political steps have been taken. In their attempt to erase the Tigers as a military threat, Indian troops are being assisted by a Tamil group, the EPRLF which was shattered two years ago when the Tigers killed some 400 of its cadres. Now the EPRLF, which unlike the Tigers accepts the peace accord and the Indian presence, is getting its revenge. Initially, its alliance with the Indian army was covert, with hooded EPRLF men identifying Tiger suspects rounded up in security sweeps. The hoods came off after the EPRLF won a majority in the November council vote, having been the only significant Tamil party to defy Tiger orders and contest the election. Now Indian troops are openly arming, deploying and sheltering members of the front.

The rebirth of the EPRLF has given the Tamil conflict a new, viciously internecine aspect, resulting in a daily toll of people killed by ‘unidentified gunmen’. The EPRLF, indiscriminately targeting not only Tiger fighters but also civilians thought to be sympathetic to them, has killed some 200 over the past three months. Says Vallipuram Pararajasingham, a doctor in the northern town of Vavuniya: ‘Today I am afraid to smile at anyone on the street. If I smile at a man who happens to be an EPRLF member or supporter, I am marked by the LTTE. If I smile at a man who has LTTE connections, I am marked by the Indian army and the EPRLF.’

Some civilians say they have been brutalized by Indian forces. Each time there is an attack on an Indian base or outpost, surrounding areas are cordoned off and large numbers of civilians are arrested and, by some accounts, beaten. Indian military officials deny the allegations of mistreatment.

The public’s anxiety over the abuses committed by Indian soldiers and EPRLF hitmen is compounded by the fact that neither force is accountable to anyone. ‘Whom do we turn to for justice when the killers are the rulers?’ asks a Tamil notary public in the Jaffna peninsula. The police force in the Northeastern province has disintegrated, and courts have not functioned for more than two years. Even if Tamils had someone to complain to, most would be too frightened to do so. ‘We don’t dare to open our mouths except to eat,’ says the uncle of an EPRLF victim.

To many Sri Lankans, the presidential election offers the only hope, if a slight one, of a diminution of the terror. Both the UNP and Bandaranaike’s SLFP sought to stop violence in the south by talking the JVP into participating in the balloting. Last May the government lifted a 1983 ban on the JVP and Prime Minister Premadasa went so far as to make the disingenuous claim that no one knew for sure that the party was responsible for the killings attributed to it. The JVP responded with more assassinations. During the fall, it linked up briefly with the SLFP-led opposition alliance – a bizarre marriage considering that a Bandaranaike government, in putting down the JVP’s 1971 revolt, killed as many as 16,000 of its people. The relationship ruptured last month when the JVP insisted on the election boycott.

On one issue, the UNP, SLFP and JVP share the same position, at least publicly: the Indians must go. The ruling party plans to maintain the Indo-Sri Lankan accord – notwithstanding the fact that presidential candidate Premadasa has opposed it from the start – but would like to send home the Indian forces as soon as possible. The SLFP originally maintained it would abrogate the pact and eject the Indians, but is now ruling out any unilateral changes. Both parties know that the Sri Lankan army is not equipped to fight both the Tamils in the north and the JVP elsewhere. Premadasa and Bandaranaike, a senior government official told TIME last week, ‘privately assure us that what they are saying is election rhetoric, but we have to wait and see what they will actually do.’

Bandaranaike’s party argues that its prescription for peace lies in a political compromise – more local authority for the Tamils – that should end the security problem in the north, thus the need for the Indian presence. Clearly, a solution will not be nearly so simple, although some observers believe that the departure of Jayewardene and a change of government would improve chances for peace. Argues the opposition’s De Mel: ‘Mrs Bandaranaike hasn’t lost her credibility the way this government has. She can deal with these equations de novo.’

The election is difficult to call. But if JVP intimidation leads to a low turnout, the ruling party should benefit, since the voters most likely to stay away are those in JVP-controlled areas, where SLFP support is strongest. But if the turnout is low and the margin of victory is narrow, the winner, whoever it is, will not be able to claim a clear mandate.

Another uncertainty is whether the mercurial Jayewardene will deliver on his promise to dissolve Parliament the day after the presidential vote in preparation for the February balloting. Postponement of those elections – the last parliamentary vote was in 1977 – would create tremendous discontent, which the JVP would surely exploit. ‘If we miss this chance for democracy, it will result in anarchy and probably a military government,’ says Anura Bandaranaike, Sirimavo’s son and the SLFP’s leader in Parliament.

Even if the elections are a success, the worst of the violence may be still to come. Says a Western diplomat in Colombo: ‘Whoever wins, somebody is going to take off the gloves and start bashing a lot harder.’ Given the seeming intractability of the several conflicts in their country, Sri Lanka is left to wonder whether it will ever regain its tranquility. Says Education Minister Wickremesinghe: ‘The media, the legal sector, the top players in government, all the institutions have been affected by the psychosis of fear. Even if all the guns are put away, this country will never be the same again.’ [Reported by Edward W.Desmond/Matara, and Anita Pratap/Jaffna]

[Note appended: “Names in quotation marks have been changed.”]

Box Profile 1: ‘Sarath’ a Sinhalese army sergeant

He is only 27, but he has the expressionless look of a man inured to death. Having fought the Tamil Tigers for five years in Jaffna, he lost ‘at least 30 friends,’ was wounded twice in mine blasts and killed ‘a lot of Tigers’. When will it end? ‘I really don’t know,’ he replies. ‘Maybe when we have a military government.’ Three months ago, his infantry unit was transferred south to take on the JVP. Looking across the empty streets of a town under a JVP curfew order, he says, ‘These people observe the curfews because they are afraid. We can’t protect every person in every house.’ He dislikes running buses, delivering food and filling the gap in basic services. Most of all, he hates fighting a shadowy enemy, going on ambushes that yield nothing, only to have morning reveal that the JVP has killed nearby during the night.

Box Profile 2: ‘Mallika’, a Sinhalese schoolteacher

The pain in the frail young woman’s face is as startling as a gunshot. Clutching her arms and pressing her lips together in an effort to hold back the tears, she tells her story, desperately, to a lawyer. Two days earlier, her husband, a merchant in a southern town, disappeared on a trip to a neighboring village. A witness saw him being stopped by what appeared to be an army patrol, though it may have been local vigilantes wearing army uniforms. After a brief discussion, the armed men got in a jeep and told her husband and his companion, another man from the village, to follow them. They drove off, and have not been heard from since. ‘I have no idea why they took him,’ she says in a strained, soft voice. ‘We don’t have anything to do with politics.’ The lawyer has checked with police and the military but has found no record of her husband’s being arrested.

Box Profile 3: B.Y.Tudawe, a Sinhalese Communist Party official

He leans forward and pulls back his shirt collar to reveal nine bumps at the base of his neck. ‘Shotgun pellets,’ he says, ‘from the first time the JVP tried to kill me.’ His forearm carries a piece of shrapnel from the second time. Despite the two near escapes, he is one of the few politicians to remain in Matara, a southern town where the JVP seems to strike almost at will. Because Tudawe is a member of the provincial council, the police provide him with four armed guards. ‘This is my place of birth, but I cannot even go out of the house without these gunmen.’ Sitting under portraits of Lenin and Buddha, Tudawe says he will stay in Matara to look after party members. He is determined to resist the JVP effort ‘to kill off all the leftists so that they can say they are the real leftists.’ This makes him a top target.

Box Profile 4: Theepan, a Tamil Tiger field commander

When he first saw Sri Lankan troops rounding up young Tamil men five years ago, he made up his mind: the only future was Eelam, an independent Tamil state. Theepan – his nom de guerre – joined the Tigers. ‘We are elated to fight the Indians,’ he says proudly. ‘The whole world admires us for the fight we have given the world’s fourth largest armed forces.’ The killing is difficult to accept, he admits, but he cites Hindu texts that justify taking life in a ‘sacred cause’. His family has suffered because of his commitment. Indian soldiers beat his father when they came looking for the guerrilla leader, but Theepan, 25, shrugs it off. ‘I don’t let my personal feelings get in the way.’ On a string around his neck he carries two vials of cyanide, which, like many Tigers before him, he has vowed to swallow rather than be captured alive.

Box Profile 5: ‘Gunarathinam’, a retired Tamil teacher

When his son, a top student, did not pass his grade-ten exams, Gunarathinam became suspicious. Then he found two grenades in the 14 year-old’s room and knew that the boy had joined the Tigers. ‘I had always dreamed about sending him to the Indian Institute of Technology in Madras,’ he says, adding sadly, ‘but we all have to contribute to the salvation of our community.’ When his son was captured by Indian troops a year ago, the youngster immediately took the cyanide escape route. Indian soldiers threw his body on the family’s front porch. Recalling that moment, Gunarathinam, 61, breaks down. The mother, still crazed by grief, hears dogs barking: perhaps an Indian patrol is prowling nearby. ‘Please go,’ she sobs to her visitors. ‘If they see you in our house, they will shoot us.’ But part of Gunarathinam is already dead.

Box Profile 6: ‘Nimal’ a Sinhalese JVP organizer

In 1983, when he decided that the established political parties ‘were saying one thing and doing another’, Nimal joined the JVP though not as a fighter. He took a one-week course in socialism taught by a JVP activist in his southern village, the only formal education he has had beyond secondary school. Today he is responsible for indoctrinating JVP recruits. Talking in urgent, impatient tones, Nimal, 33, insists that Sri Lanka’s problems began with the intervention of India, acting as an ‘agent for American imperialism.’ To him, the future is clear: ‘There are only two solutions to Sri Lanka’s current troubles – independence [from Indian intervention] or death.’ He admits that the JVP has done a lot of killing, but ‘never of innocent people.’ Three of his friends have been killed by the security forces, but he is not afraid.

Box Profile 7: Jayamani Marianayagam, a Tamil mother

Her 17 year-old son was practicing You Are My Rock, O Jesus on the organ in Jaffna’s St.Mary’s Church when a gun battle between the Tigers and the rival EPRLF erupted outside. A wounded Tiger stumbled into the church, his enemies in pursuit. They grabbed young Jayamani. The boy’s body was found that night near the church, his legs broken, his finger nails missing, his head half blown away. Jayamani, 41, cried the night away, holding the remains of her son. ‘No mother should ever have to face the tragedy of seeing her son like that.’ She is terrified that her two younger boys, 15 and 13, will also become victims or join the Tigers to seek revenge. Her husband works as a waiter in a West German hotel. She wants to take the children and join him, but last year a travel agency cheated her out of the family savings.

*****

The Killing Campaign; Violence dominates Countdown to Presidential Poll

[Manik de Silva, Far Eastern Economic Review, Dec.22, 1988, p. 23.]

Even as the countdown began for the 19 December presidential election, regarded as the most crucial in recent Sri Lankan history, the killing continued. Both in the troubled north and east, where Tamil separatist guerillas have taken on the Indian army, and in the southern Sinhalese districts where subversive and counter-subversive activity is rife, there is a frightening daily toll of lives. According to the latest official tally, the 30 days ending 15 November had seen a total of 112 political killings in the Sinhalese south. In the north and the east, 32 people were killed during the same period.

Since then, there has been an average of about six political killings every day in the southern districts, with fewer deaths in the north and east. The presidential campaigns of the two principal contenders – Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, 64, and former prime minister Sirima Bandaranaike, 72 – are taking place in an environment of unprecedented disruption.

Meanwhile, the third candidate, Ossie Abeygoonasekera of the Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya (SLMP, or People’s Party), barely escaped two attempts on his life at election rallies. He is the only candidate to publicly accuse the Sinhalese Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP, People’s Liberation Front) of responsibility for the violence that is widely attributed to it.

Premadasa says that there is no proof that the JVP is responsible for the killings and the disruption, while Bandaranaike, whose Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) once announced JVP-backing for her candidature, alleges the violence is caused by retaliatory hit squads set up by the ruling United National Party. The issues are clear for voters. Both Premadasa and Bandaranaike have pledged to send the Indian Peace-Keeping Force of 50,000 troops back home. Bandaranaike is committed to scrap the 1987 Indo-Sri Lanka peace accord while Premadasa says he will replace it with a friendship treaty. Premadasa, who distanced himself from the accord at the time it was signed by retiring President Junius Jayewardene, has subsequently visited India to mend fences. Bandaranaike also is all too conscious of the geopolitical realities. Only Abeygoonasekara backs the accord.

Premadasa, who does not hail from the well-educated land-owning or professional elites from which post-independence Sri Lanka has traditionally drawn its leaders, has made a strong pitch as the ‘common man’, aware of the problems and aspirations of ordinary people. Bandaranaike says that he can hardly be a common man after 10 years as prime minister.

Both have pledged to restore law and order, the issue that can swing the election to see an end to the killing and the economy-sapping disruption. Bandaranaike has refrained from saying that she smashed the JVP in 1971 when it rose against her government, Premadasa discounts the government’s failure on the law-and-order issue by saying that no powers are vested in him.

All three candidates were stumping in the predominantly Tamil Northern Province during the last week of the campaign. On 9 December, National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali told parliament that Bandaranaike’s son, Anura, and Kumar Ponnambalam of the All-Ceylon Tamil Congress, an SLFP ally in the Democratic People’s Alliance (DPA) which has been forged to back Bandaranaike, had secret talks with leaders of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the dominant Tamil separatist group, on 6 December. Bandaranaike and Ponnambalam confirmed the meeting, but said many of the details in Athulathmudali’s statement were incorrect.

While saying that Athulathmudali, too, had once attempted to meet the LTTE through Ponnambalam’s intercession, they were silent on the substance of the talks and whether any deal had been swung. But within 48 hours of the SLFP-LTTE meeting being publicized, the government claimed that communication intercepts of contacts between the LTTE leadership and its ranks revealed that the LTTE had told its cadres to back Bandaranaike on 19 December.

Many observers in Colombo believe that despite the best efforts of the two major contenders, Abeygoonasekera may get more Tamil votes in the north and east than either Premadasa or Bandaranaike. There are links between the SLMP and the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) which won last month’s election to run the temporarily merged Northern and Eastern provinces. The EPRLF is trying to reach an accommodation with the LTTE, which boycotted and tried to prevent voters from participating in the provincial council elections.

Premadasa’s supporters hope that a poverty-alleviation programme, a major plank of his platform, offering food stamp families – there are 7 million food stamp recipients in the country – a monthly dole of Rs 2,500 (about US$ 75) per family for two years could win him many votes. Premadasa said that the payment would enable each family to build up a nest egg of Rs 25,000 in two years and launch small income-generating enterprises with it. The SLFP has denounced the scheme as a promise that cannot be kept as the country would never be able to afford it.

Many observers believe that a low voter turnout would be advantageous to Premadasa while a high turnout could carry Bandaranaike to victory. The SLFP leader agrees with this assessment and in recent speeches has been exhorting her supporters to vote early and without fear. At the last three national elections, the voter turnout was 80%, but the recent provincial council elections, boycotted by the SLFP and disrupted by the JVP without any SLFP protest, saw many people who might otherwise have voted, stay home.

Government intelligence expected subversive action – which has crippled much of the country outside Colombo and placed as much strain on the electoral system as the economy – to peak in the final week’s run-up to the poll.

*****

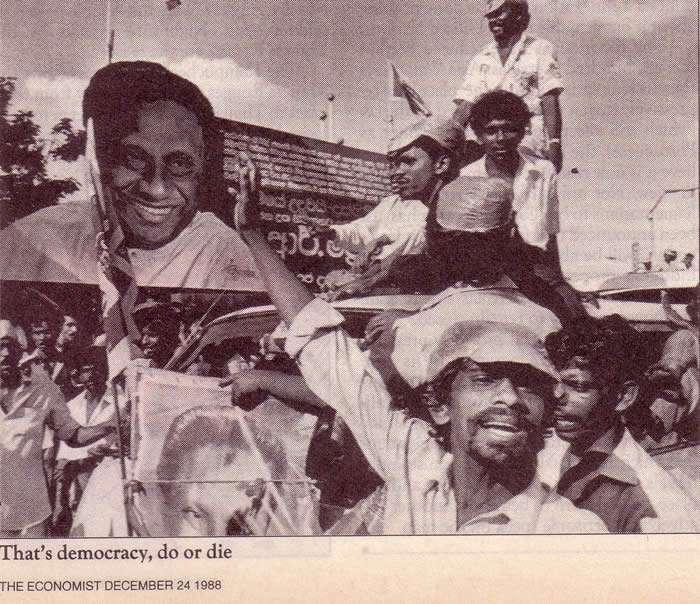

Democracy’s Day of Courage

[Sri Lanka Correspondent, Economist, Dec.24, 1988, p. 33.]

There cannot have been an election like it, certainly never in Sri Lanka. People risked their lives to vote, and 18 were shot dead, either queueing at the polls or returning from them. Gunmen attacked 20 polling stations. Fifty stayed closed because the staff were afraid to turn up. Yet there was a turnout of 55%, well down from the 80% or so of previous elections, but a brave effort by a democratic-minded people determined not to surrender to gun law.

Mr Ranasinghe Premadasa, the successful candidate, and thus Sri Lanka’s next president, said as he cast his own vote on December 19th that this was a contest between the ballot and the bullet. ‘I am sure that the ballot will win.’ He was right. Mr Premadasa won a more personal battle. Although most commentators had predicted a close contest, the best guess was that 72 year-old Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, of the opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party, had the edge. The argument was that Sri Lankans wanted a change, if only to see whether an entirely new administration could end the country’s communal troubles.

For ten years Mr Premadasa has been prime minister, under the outgoing president, Mr Junius Jayewardene. If that was a liability, a worse one appeared to be that he belonged to a low caste, that of the laundrymen. He grew up in a rundown area of Colombo, without the benefit of an expensive education provided by wealthy parents. Sri Lanka’s previous leaders, including Mrs Bandaranaike, a former prime minister, have been of high caste. Nevertheless, the 66 year-old Mr Premadasa tipped the balance, winning 50.4% of the votes. Mrs Bandaranaike got 44.9%. The candidate of the left-wing People’s party, Mr Ossie Abeygoonasekera, who survived two assassination attempts during the campaign, picked up the rest.

Mr Premadasa’s intense campaigning and the United National Party’s superior organization won him support across the country. He even did well in the southern rural districts where the gunmen of the People’s Liberation Front, or JVP (for Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna), are most active and did their deadly best to stop the voting.

All that was left for Mrs Bandaranaike was the anti-government vote that had built up over five years of unparalleled unrest in Sri Lanka, plus the support of white-collar suburbanites prepared to forgive her for the shortages that marred her government of 1970-77. It did not do. Mrs Bandaranaike suffered the ignominy of losing her hometown of Balangoda. She did not turn up for the formal results and left for the country in a sulk, saying the election was unfair.

One of the new president’s first problems, when he takes over on January 2nd, will be to decide what to do about the JVP, the anti-government Sinhalese terror group which is believed to have killed more than 600 people over the past year. In his victory speech, Mr Premadasa appealed to it to talk to him in a friendly fashion. He is perhaps the only major politician to have escaped criticism from the JVP. The Front appears to have made a distinction between the executive president, Mr Jayewardene, whom it has tried to kill, and Mr Premadasa, whom it has praised as a ‘patriotic leader’.

The Front and the president-elect have a common cause in their anti-Indianism. Mr Premadasa was against last year’s India-Sri Lanka agreement which brought 50,000 Indian troops to the north and east to disarm Tamil guerrillas seeking a separate state. The JVP calls them the invading forces of the Indian imperialists. Mr Premadasa promised to make the Indians go. This should please the Front, as should the dissolution of parliament announced on December 20th. The country’s first parliamentary election in 12 years will be held on February 15th.

What will become of the accord with India? Mr Jayewardene says it is a fixture. The limited self-rule it promised to Tamils in the form of a provincial council for the north and east is now functioning. Only the Tigers, of all the separatist fighters, remain on the loose, but they now seem weak as kittens because of the presence of the Indians. Those close to Mr Premadasa say he may replace the accord with a ‘friendship treaty’, whatever that means. He may then ask the Indians to start pulling out. This, he hopes, will keep the JVP quiet. Perhaps. But the real aim of its Marxist leaders may be to force a revolution in which it can come to power.

Mr Premadasa’s promises of peace, an end to poverty, and the removal of the Indian forces without resurrecting the Tigers, will be hard to keep. Mr Jayewardene, still the ‘old fox’ at 82, will be watching attentively as he shuffles slyly to the sidelines.

*****

Patching an Old Feud: Gandhi’s Beijing visit aims to end decades of mutual mistrust

[ Michael S. Serrill; Time, Dec. 26, 1988, p. 23]

Excerpts:

Only 18 months ago, Indian and Chinese troops were massing along their disputed Himalayan frontier in what threatened to become another military face-off between the world’s two most populous nations. Last week the two powers were preparing for a new and, it was hoped, more pleasant era of bilateral relations: New Delhi and Beijing were laying the groundwork for a five-day visit to China this week by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the first such call by an Indian leader in 34 years….

A cynical view holds that Gandhi would welcome an opportunity to offset his unsuccessful effort to gurantee a settlement in the Tamil-Sinhalese confrontation in neighboring Sri Lanka. His July 1987 attempt to resolve the conflict through an agreement with President Junius Jayewardene helped spark a bloody reaction by Sinhalese militants, who resent what they consider India’s infringement on Sri Lankan sovereignty. India’s 70,000 – member peacekeeping force on the island now finds itself embroiled in a guerrilla war that has left nearly 700 Indian soldiers dead, along with 4,300 Sri Lankans….[reported by Sandra Burton/ Beijing and Anita Pratap/ New Delhi].

*****

Breakout; An explosive prison escape

[ Anonymous; Time, Dec. 26, 1988, p. 24]

The break should not have been that easy. Air force guards, armed with automatic rifles, were on alert in the watchtowers of Colombo’s high security New Magazine Prison. The inmates, members of the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), the violent Sinhalese group that seeks to overthrow the government of President Junius Jayewardene, were locked up in two cellblocks inside. Suddenly two flares arced over the compound, and prison security unraveled, permitting the second biggest jailbreak in Sri Lankan history last week.

As about 20 gunmen opened fire on the New Magazine guards from a lane outside the walls, the doors to the blocks housing JVP detainees opened. Several prisoners charged out to place an explosive device near the prison wall and detonated it electronically, blasting open a 5-ft. hole. Within minutes, 221 prisoners ducked through and ran 80 yds. Across a stretch of cleared land. They scaled a second 6 ft.-high brick wall, then scattered in all directions, leaving behind six men who were shot dead by soldiers. By midweek the government claimed that 15 more escapees had been killed and 35 recaptured by security forces, who imposed a curfew on parts of the capital as they searched for escapees.

The mass break was the fourth by JVP militants in just two months; in earlier escapes, 162 members of the extremist group had gained freedom. Last week’s carefully planned effort had all the markings of an inside job, and authorities quickly launched an investigation into the affair. While the possibility of JVP infiltration of the police and the armed forces has worried the government for sometime, the jailbreaks heighten the threat to the Jayewardene regime: the JVP now has more muscle behind its vow to use terror to disrupt presidential elections scheduled for this week to determine a successor for Jayewardene.

To underscore their determination, JVP terrorists killed at least 85 people last week, mostly in the south of the island, and warned newspapers to avoid publishing articles on the impending vote. Security forces and anti-JVP vigilantes continued their own counterterror action, which claimed about 40 lives last week. Saying that elections could not take place in the midst of the killing, opposition leaders met with the President and urged him to cancel the balloting. Jayewardene was determined that the voting would go on as scheduled, but the sudden restoration of 165 cadres to the JVP’s ranks was a painful setback. ‘The situation was bad before,’ said a senior government official. ‘Now it is much worse.’

*****

[Error.] |