Ilankai Tamil Sangam28th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

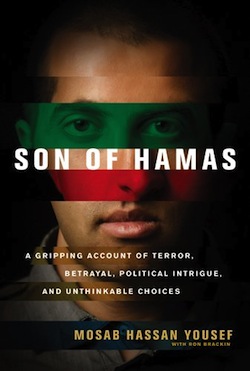

'Son of Hamas'

Israel’s Informers by Dan Ephron, Newsweek, May 10, 2010

I had a chance a few years ago to put the question to a senior official in Shabak, the Israeli security agency in charge of maintaining order in the West Bank. The official, who had just retired, said Shabak kept lists of every Palestinian in every town and village and ranked them in order of their potential usefulness. A Palestinian apt to be particularly well informed—the head of a clan or the brother of a top militant—would appear near the top of the list. Alongside each name, Shabak officials would write something about the person’s personal life that could be leveraged in recruiting him as a spy. One might be waiting for permission to have his child treated in an Israeli hospital. Another might have a grudge against a certain clan known to be involved in suicide attacks. When agents needed informers in a certain area, they would consult the lists and go to work. Mosab Yousef’s name must have appeared near the top of one of these lists. As the son of a Hamas founder, he knew many of the group’s political and military leaders. He was privy to their discussions and was occasionally in attendance when critical decisions were made. When Israel arrested Yousef in 1996 for buying guns, an affable Shabak agent set about recruiting him. The result, described in Yousef’s intriguingly detailed but also unabashedly self-serving memoir, Son of Hamas, was a decade-long career as a spy for Shabak during which Yousef comes around to siding largely with Israel in its conflict with the Palestinians, helps foil suicide attacks, and eventually converts to Christianity. His account underscores the role intelligence played (alongside construction of the security barrier) in eventually suppressing the second intifada. The most interesting passages of the book reveal an aspect of intelligence work almost never discussed publicly: the way an agency woos informers and gets them to betray their own community. Yousef’s Shabak handler, Loai (the name he’s given in the book), does it mostly through charisma and persuasion. He speaks to Yousef in perfect Arabic, shows an astonishing familiarity with Yousef’s life in the West Bank, gives him money for college and clothes, and cultivates him for a long time before asking for anything in return. All along, Loai frames the work Yousef does for Shabak as a blow against zealots on both sides of the conflict and a boon for peace. “What the Israelis were teaching me was more logical and more real than anything I had ever heard from my own people,” Yousef writes. “Nearly every time we met, another stone in the foundation of my world view crumbled.” Though Son of Hamas is primarily an account of one man’s undercover work, it occasionally comes across as a story about the complicated relationship of fathers and sons. Yousef repeatedly professes admiration for his father, Hassan Yousef, and maintains that his work for Shabak helped keep his father off Israel’s targeted-assassination list (though not out of jail). But he’s contemptuous of the way his father rationalizes suicide attacks. Eventually, Yousef grows tired of the double life, quits Shabak, and moves to the U.S., where he completes his conversion to Christianity. When he tells his father by phone from California that he’s no longer a Muslim, the elder Yousef cries in his jail cell. In a subsequent call, Yousef delivers the news that he’d been a spy for Israel. The response this time: stone-cold silence. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chapter One — Captured — 1996 I steered my little white Subaru around a blind corner on one of the narrow roads that led to the main highway outside the West Bank city of Ramallah. Stepping lightly on the brake, I slowly approached one of the innumerable checkpoints that dot the roads running to and from Jerusalem. "Turn off the engine! Stop the car!" someone shouted in broken Arabic. Without warning, six Israeli soldiers jumped out of the bushes and blocked my car, each man carrying a machine gun, and each gun pointed directly at my head. Panic welled up in my throat. I stopped the car and threw the keys through the open window. "Get out! Get out!" Wasting no time, one of the men jerked open the door and threw me to the dusty ground. I barely had time to cover my head before the beating began. But even as I tried to protect my face, the heavy boots of the soldiers quickly found other targets: ribs, kidneys, back, neck, skull. Two of the men dragged me to my feet and pulled me to the checkpoint, where I was forced onto my knees behind a cement barricade. My hands were bound behind my back with a sharp-edged plastic zip tie that was cinched much too tight. Somebody blindfolded me and shoved me into the back of a jeep onto the floor. Fear mingled with anger as I wondered where they were taking me and how long I would be gone. I was barely eighteen years old and only a few weeks away from my final high school exams. What was going to happen to me? After a fairly short drive, the jeep slowed to a halt. A soldier pulled me from the back and removed my blindfold. Squinting in the bright sunlight, I realized that we were at Ofer Army Base. An Israeli defense base, Ofer was one of the largest and most secure military facilities in the West Bank. As we moved toward the main building, we passed by several armored tanks, which were shrouded by canvas tarps. The monstrous mounds had always intrigued me whenever I had seen them from outside the gates. They looked like huge, oversized boulders. Once inside the building, we were met by a doctor who gave me a quick once-over, apparently to make sure I was fit to withstand interrogation. I must have passed because, within minutes, the handcuffs and blindfold were replaced, and I was shoved back into the jeep. As I tried to contort my body so that it would fit into the small area usually reserved for people's feet, one beefy soldier put his boot squarely on my hip and pressed the muzzle of his M16 assault rifle into my chest. The hot reek of petrol fumes saturated the floor of the vehicle and forced my throat closed. Whenever I tried to adjust my cramped position, the soldier jabbed the gun barrel deeper into my chest. Without warning, a searing pain shot through my body and made my toes clench. It was as if a rocket were exploding in my skull. The force of the blow had come from the front seat, and I realized that one of the soldiers must have used his rifle butt to hit me in the head. Before I had time to protect myself, however, he hit me again, harder this time and in the eye. I tried to move out of reach but the soldier who had been using me for a footstool dragged me upright. "Don’t move or I will shoot you!" he shouted. But I couldn't help it. Each time his comrade hit me, I involuntarily recoiled from the impact. Under the rough blindfold, my eye was beginning to swell closed, and my face felt numb. There was no circulation in my legs. My breathing came in shallow gasps. I had never felt such pain. But worse than the physical pain was the horror of being at the mercy of something merciless, something raw and inhuman. My mind reeled as I struggled to understand the motives of my tormentors. I understood fighting and killing out of hatred, rage, revenge, or even necessity. But I had done nothing to these soldiers. I had not resisted. I had done everything I was told to do. I was no threat to them. I was bound, blindfolded, and unarmed. What was inside these people that made them take such delight in hurting me? Even the basest animal kills for a reason, not just for sport. I thought about how my mother was going to feel when she learned that I had been arrested. With my father already in an Israeli prison, I was the man of the family. Would I be held in prison for months and years as he had been? If so, how would my mother manage with me gone too? I began to understand how my dad felt — worried about his family and grieved by the knowledge that we were worrying about him. Tears sprang to my eyes as I imagined my mother's face. I also wondered if all my years of high school were about to be wasted. If I indeed was headed for an Israeli prison, I would miss my final exams next month. A torrent of questions and cries raced through my mind even as the blows continued to fall: Why are you doing this to me? What have I done? I am not a terrorist! I'm just a kid. Why are you beating me like this? I'm pretty sure I passed out several times, but every time I came to, the soldiers were still there, hitting me. I couldn't dodge the blows. The only thing I could do was scream. I felt bile rising in the back of my throat and I gagged, vomiting all over myself. I felt a deep sadness before losing consciousness. Was this the end? Was I going to die before my life had really even started? From Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable Choices, copyright 2010 by Mosab Hassan Yousef. Published by SaltRiver, an imprint of Tyndale House Publishers Inc.

| ||

During the second Palestinian uprising, which I covered from 2001 to 2005, I often found myself wondering how Israeli intelligence officials knew so much about the inner workings of Hamas and the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. The groups, instigators of dreadful violence against Israel, operated in small cells in utter secrecy. Yet on more than 200 occasions during the intifada, Israel managed to find and kill their top operatives in pinpoint strikes, often by firing airborne missiles at their cars as they traveled from one safe house to another. “Targeted assassinations,” as Israel described the killings, required real-time information from people high enough in the ranks of these organizations to know the whereabouts of the most sought-after fugitives. How could Israel have recruited so many well-placed informers?

During the second Palestinian uprising, which I covered from 2001 to 2005, I often found myself wondering how Israeli intelligence officials knew so much about the inner workings of Hamas and the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. The groups, instigators of dreadful violence against Israel, operated in small cells in utter secrecy. Yet on more than 200 occasions during the intifada, Israel managed to find and kill their top operatives in pinpoint strikes, often by firing airborne missiles at their cars as they traveled from one safe house to another. “Targeted assassinations,” as Israel described the killings, required real-time information from people high enough in the ranks of these organizations to know the whereabouts of the most sought-after fugitives. How could Israel have recruited so many well-placed informers?