Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 18: The First Sinhalese- Tamil Riftby T. Sabaratnam, December 18, 2010

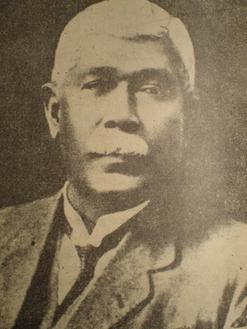

Manning Reform Arunachalam was overjoyed at the founding of the Ceylon National Congress. He felt satisfied that his dream of creating a united Sri Lanka had borne fruit. He gave vent to his satisfaction in his presidential address when he inaugurated the Ceylon National Congress on December 11, 1919 at the Public Hall, Colombo. He proclaimed:

He concluded his address quoting from the ‘Karaniya Metta Sutta’,

The Sinhalese and the Tamils were also overjoyed. I quoted last week the comment made by the Ceylon Daily News. The newspaper called the Congress a “great advance” and said that all those who worked to bring it into existence had reason to be proud of its achievement. Indu Sathanam reflected the satisfaction of the Tamil people. It said,

Arunachalam’s presidential address to which Colombo newspapers gave prominence created a stir in Jaffna. The progressive sections of the youth welcomed it. It strengthened the progressives in the Jaffna Association who supported Sri Lankan nationalism. That group was proud that the Tamils were giving the lead to the growth of Sri Lankan nationalism. But the others were still not sure whether that attempt would succeed. They were convinced that unless strong safeguards were built into any constitutional arrangement the Sinhalese would grab the state power and marginalize the Tamils. For the next two years it looked that Arunachalam’s dream of building Sri Lankan Nationalism had worked. Sinhalese and Tamils stepped up their agitation for constitutional reform under the guidance of the Ceylon National Congress. The unity between the two communities grew stronger. Indu Sathanam reflected the new optimism and enthusiasm thus:

The feeling that Sinhalese and Tamils belong to the Sri Lankan nation grew among the leaders and the people of both communities. The Ceylon National Congress submitted to the British government the resolution adopted in the December 11, 1919 inaugural conference. Arunachalam had great hopes of building Sri Lankan nationalism. He started a daily Tamil newspaper ‘Desanesan’, the first Tamil daily published in Sri Lanka. He and E.V. Ratnam appointed Natesa Iyer, a Tajavoor Brahmin, who later became a trade unionist and a member of the Legislative Council, as the editor.

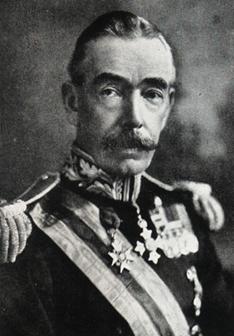

The paper took up the cause of the plantation workers and Natesa Iyer published a series of investigative articles exposing the miserable conditions under which Indian Tamil workers lived and worked. The paper though short lived created an impact by campaigning for the building of Sri Lankan nationalism and the abolition of the Thundu System. Arunachalam’s dream of building a united Sri Lanka based on Sri Lankan nationalism was dashed with the announcement of the reconstitution of the Legislative Council in August 13, 1920. When Governor Sir William Manning (1918-25) forwarded the resolutions of the Ceylon National Council and the various representations made to him for the consideration of the Colonial Secretary he wrote, "Every community shall be represented and while there is a substantial non-official majority, no single community can impose its will on other communities if the latter are supported by the official members." The Secretary of State for Colonies, after considering the representation of different sections of opinion, procured an Order-in-Council, of August 13, 1920, reconstituting the Legislative Council. There were to be a total of 37 members - 14 officials and 23 unofficials. Eleven of the unofficials were to be elected on a territorial basis and five others to represent the Europeans, two for Burghers, one to represent the Chamber of Commerce, two nominated seats were given to the Kandyans and one each to the Indians and Muslims. For the first time, in the history of Sri Lanka it had an unofficial majority of nine members. Of the 11 elected seats the highly populated Western Province was allocated four and the other provinces one each. The seats allocated to the Western Province were: Western Province South A seat, Western Province South B seat, Colombo West seat and Colombo Municipal seat which was also called Colombo Town seat. Manning conceded in his reforms the demand of the Ceylon National Congress that unofficial members should form the majority in the Legislative Council. He did not concede the demand that all unofficial members should be elected territorially. He permitted only 11 unofficials to be territorially elected and eight through communal electorates. He also favoured the Kandyans with higher representation. When the time for the election for the territorial seats arrived, Arunachalam was prepared to file his nomination papers for the seat of Colombo Town. Immediately, a Sinhalese militant group headed by F. R. Senanayake which had gained control of the Congress started a campaign against him. That group had also managed to oust Arunachalam from the Congress presidency and had elected James Peiris for that post. F.R. Senanayake and his brother D.S. Senanayake, friends of Anagarika Dharmapala, came into prominence through the Temperance Movement. Arunachalam began to lose faith in the Sinhala leaders soon after the inauguration of the Ceylon National Congress. His efforts to mould the Ceylon National Congress on the lines of the Indian National Congress which rose above regional nationalism and interests were resisted by the group led by F.R. Senanayake. Arunachalam later said they refused to rise above Sinhala nationalistic interests. They viewed every issue from the stand of Sinhala nationalism. The breaking point came before the 1921 Legislative Council election. Arunachalam asked Peiris and Samarawickrama that Colombo Town seat be allocated to him in accordance to the agreement reached during the formation of the Ceylon National Congress. They turned down Arunachalam’s request saying that the acceptance of his request would mean the acceptance of the principle of communal representation. When pressed further they said that the pledge given in their capacity of presidents of the association which existed at that time had no binding on them as officials of the Ceylon National Congress. H.C. Pereira, an influential member of F.R. Senanayake group, went a step further. He argued,

F.R. Senanayake branded Arunachalam "an egoist who had an exaggerated notion of his importance and an extremist in politics". His group started a campaign saying that Sinhala electorates should elect real Sinhalese. The Ceylon National Congress announced the candidature of James Peiris for the Colombo Town seat. Arunachalam was intensely distressed over this betrayal. He was nearing his seventies by that time. He announced his resignation from the Ceylon National Congress and returned to Jaffna a disappointed man. Sir. A. Kanagasabai and A. Sabapathy, the two nominated Tamil members in the Legislative Council also resigned. All the Tamil members in the Ceylon National Congress too resigned. That was the first instance Tamils resigned en masse from a national organization. Their resignation reduced the Ceylon National Congress to a Sinhala organization. The election was held in March 1921. Peiris was elected uncontested for the Colombo Town seat and his brother-in-law H.A. de Mel was elected uncontested to Colombo West. W.W. Rajapaksa was elected uncontested to the Western Province A seat and E.W. Perera won the Western Province B seat. Of the 11 seats for which the election was held F. Duraswamy won the Northern Province seat and E.R. Tambimuttu won the Eastern Province. The other nine seats went to the Sinhalese. With the nomination of Ramanathan by the Governor the number of Tamils in the Legislative Council rose to three. With the nomination of two Sinhalese their number rose to 11. Some historians blame Manning for the break up of the Ceylon National Congress. Some others blame the two brothers-in-law, James Pieris and H.L.de Mel, for that disaster. Those who blame Manning say that he deliberately devised a hybrid system of territorial representation to exploit the Sinhala - Tamil rivalry. They also say that he exploited the caste difference among the Sinhala people and the rivalry between the Kandyan Sinhalese and the Low Country Sinhalese. They argue that Manning had formed an aversion to the Ceylon National Congress because he realized that the rooting and growth of Sri Lankan nationalism would pose a threat to the British rule. They blame the Manning Reforms for suppressing the emerging nationalist consensus. K.M. de Silva is of such a view. He deals with that aspect of the story in his A History of Sri Lanka in the section Ceylon National Congress in Disarray (pages 484-491). He said,

Some accuse the brothers-in-law for Arunachalam’s resignation from the Ceylon National Congress. They say their greed for political power was the real cause for the trouble. Still others blame F.R. Senanayake’s racism. Former Secretary General of the House of Representatives Sam Wijesinghe is one who blames the brothers-in-law. In an Arunachalam memorial speech he said,

The rift between the Sinhalese and the Tamils was commented on by several newspapers published in Colombo and Jaffna. Indu Sathanam headlined its editorial, “Rift between the Sinhalese and Tamils”. It said the Sinhalese leaders had totally refused to allocate the Western Province seat to the Tamils which they pledged to do. It portrayed the impact of that action on the Tamils thus:

The feeling of frustration caused among the Tamils by this incident was commented on by the other Jaffna newspapers also. The Hindu Organ then the most popular paper said in its editorial,

The Morning Star and Uthaya Tharakai too wrote editorials reflecting the frustration of the Tamils. The Morning Star said,

Arunachalam in an interview to The Times of Ceylon of December 14, 1921 recounted the events that led to his resignation from the Ceylon National Congress. He said that only those who had been in the inner councils of the reform movement could know the difficulty with which all communities were brought together on a common platform, the ceaseless toil and tact that were needed to remove ancient prejudices and jealousies, to harmonize dissensions and to create the indispensable basis for mutual trust and cooperation. He added,

Peiris and Samarawickrama wrote to Manning saying that Arunachalam withdrew because his ambition to be in the Legislative Council could not be achieved. Arunachalam denied that accusation, in the reply he sent to the governor. He said,

The breaking of a solemn pledge for the sake of benefitting James Peiris created a deep rift between the Sinhalese and the Tamils which affected deeply the course of the history of the country. That also strengthened the hands of the ‘communal representation’ group within the Jaffna Association. Sabapathy and Kanagasabai adopted a stronger stand in support of their demand for communal representation. The influence Indian nationalism had on the Tamil people weakened considerably. That was the time the Jaffna Association was divided into the ‘communal representation group’ and the ‘progressive group’. The ‘communal representative group’ which was also called the “safeguard group’ consisted of elderly conservative men who followed the Ramanathan- Arunachalam line of approach: building a united Sri Lanka within which the interests of the Tamil people should be safeguarded through communal representation. They were also influenced by the Indian independence movement to a certain extent. The ‘progressive group’ was made up of vibrant youngsters mostly the products of Jaffna College and graduates of Madras and Calcutta universities, centres that were in the forefront of the Indian independence movement. They entertained the vision of building a united independent Sri Lanka. The ‘progressive group’ was disappointed when Arunachalam resigned from the Ceylon National Congress. Arunachalam was engaged in a prolonged war of words with his former Sinhala colleagues before he formed the Tamil Mahajana Sabhai. He accused the Sinhala leaders of self interest and of failure to realize the importance of building Sri Lankan nationalism. Arunachalam said in a statement that the most devastating effect that the breaking of the pledge would have was the profound distrust the Tamils may develop about the Sinhala leaders. He said,

The Tamil Mahajana Sabhai was formed at a meeting held in Jaffna on August 15, 1921. Representatives of all organizations in the Jaffna district and other parts of the country were invited. The Ceylon Observer reported that meeting in detail. It said,

In his address Arunachalam said the meeting had brought all Tamils under one banner to serve the aspirations of the Tamils as a whole. W. Duraisway proposed the first resolution. Its text:

Uthaya Tharakai, in its editorial, welcomed the formation of the Tamil Mahajana Sabhai. It said,

Members of the Jaffna Association attended the inaugural meeting of the Tamil Mahajana Sabhai in full strength. Its president Sabapathy was elected one of the vice presidents. The progressive wing of the Jaffna Association joined the Tamil Mahajana Sabhai in the hope that it would serve Arunachalam’s ideal of promoting Sri Lankan nationalism. Among those who joined were: Handy Perinbanayagam, C. Balasingham, S. Balasundaram, P. Kandiah, T.N. Subbaiah, M.S. Eliyathamy, Kalai Pulavar Navaratnam, T.C. Rajaratnam and P. Nagalingam. They were soon disillusioned. Nagalingam with whom I worked in the Lanka Sama Samaja Party in the 1956 and 1960 general elections told me that they made continuous efforts to get Arunachalam back on track: his goal of Sri Lankan nationalism. They found that he could not get over the effect of the betrayal by his former Sinhala colleagues. They found that his health too was affected by the trauma he underwent during the struggle he had in the Ceylon National Congress. The progressive youth group found to their astonishment that the Tamil Mahajana Sabhai was also slipping into the hands of the Kanagasabai-Sabapathy ‘communal representation’ group that dominated the Jaffna Association. It also took up the demand for communal representation. The ‘progressive group’ pressurized Arunachalam to correct the situation and get back to his wider perspective of serving the Tamils and the country. Arunachalam who had not completely abandoned his wider view was uncertain about the course he should follow. Under heavy pressure from the progressive youth he decided to form another organization to serve his wider view of serving the Tamils and the country. He founded the Ceylon Tamil League on September 15, 1923. In Tamil it was named Ilangai Tamil Makkal Sangam. Addressing the inaugural sessions Arunachalam said,

This address reflected the struggle that was going in Arunachalam’s mind. He was talking in the same breath about serving Sri Lanka and about Tamilakam. But he did not live to explain his views. He went on a pilgrimage to the Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu. He died in Madurai on January 9, 1924. 1924 Reforms The new Legislative Council met in June 1921. James Peiris, the president of the Ceylon National Congress which was not satisfied with the reformed council, moved an amendment to the Order-in-Council of 1920. He placed the resolutions embodying the proposals of the Ceylon National Congress for the consideration of the Legislative Council. Peiris attacked the 1921 reforms on two grounds: the veto power of the governor and the retention of communal representation. He proposed that the council should have 45 members, of whom six were to be officials, 28 territorially elected; communal and minority representations to be retained with slight alterations; an elected Speaker; the Executive Council should have three official members and three unofficial members chosen from the members of the Legislative Council; the repeal of the governor's powers to stop debates and other changes. E.W. Perera, spokesman of the Ceylon National Congress, made use of the debate to attack the extension of the scheme of communal representation. He called it a return to tribalism. He insisted that the system of communal representation should be done away with. Ramanathan in his reply said territorial representation was suited only to countries with a homogeneous population and not to Sri Lanka where more than one race lived. In his reply he said,

The five communities Ramanathan referred to were : Tamils, Muslims, Indians, Burghers and Europeans. Ramanathan continued,

Ramanathan then explained why they asked for communal representation. He said,

Following the resolution moved by James Peiris, Ramanathan drafted a joint-memorandum with the help of leaders of other minority communities and submitted it to Manning. In that joint- memorandum Ramanathan advocated communal representation. He claimed that his scheme would enable” the voice of the minorities to be heard in the council”. He added, “It is a scheme to safeguard the interests of the Tamils and other minorities in the country.” Ramanathan told the press the reason behind his decision to present a joint- memorandum thus,

Manning forwarded to the Secretary of State for Colonies the resolution passed in the Legislative Council and the memoranda submitted by Ramanathan and others with his note on March 1, 1922.which contained the following passage:

Clause 52 provided that if the Governor deemed the passing of any bill of paramount importance, only the votes of the official members and the nominated official members, not those of the unofficial members needed to be taken into account for the bill to be passed. The Secretary of State replied on January 11, 1923 that he agreed with the Governor that … in view of the existing conditions and the grouping of population in the colony, representation must for an indefinite period of time be in fact communal, whatever the arrangement of constituencies may be , and that of all the elected members were in form returned by territorial constituencies would none the less be in substance communal representations. The two statements (highlighted by me) and Manning’s clever strategy employed in the 1924 reforms to balance the numbers of the representatives of the Sinhalese and the minority communities altered the demand of the Tamils from communal representation to balanced representation. While the ‘communal representation’ group of the Jaffna Association adopted Manning’s bait youths of the ‘progressive group’ saw through it. The youth took up the failing Ramanathan-Arunachalam conviction on Sri Lankan Nationalism and led the Tamils on the wrong and fruitless path. Tamils suffered politically owing to their misdirected enthusiasm in the 1920s and 1930s. It cannot be totally ruled out as wasted years. Tamil society underwent a revolutionary change. Next: "The Birth and Death of the Jaffna Youth Congress" ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Index Chapter 2: Origins of Racial Conflict Chapter 3: Emergence of Racial Consciousness Chapter 4: Birth of the Tamil State Chapter 5: Tamils Lose Sovereignty Chapter 6: Birth of a Unitary State Chapter 7: Emergence of Nationalisms Chapter 8: Growth of Nationalisms Chapter 10: Parallel Growth of Nationalisms Chapter 11: Consolidation of Nationalisms Chapter 12: Consolidation of Nationalisms (Part 2) Chapter 13: Clash of Nationalisms Chapter 14: Clash between Nationalism Intensifies Chapter 15: Tamils Demand Communal Representation Chapter 16: The Arunachalam Factor Chapter 17: The Arunachalam Factor (Part 2) Chapter 18: The First Sinhala - Tamil Rift Chapter 19: The Birth and Death of the Jaffna Youth Congress |

|||||

|

||||||