Front Note by Sachi

On April 23, I received an unexpected email from a German scholar from Hamburg. It read as follows:

“Vanakkam! I am a research scholar working on Tamil at the University of Hamburg, Germany. I am currently working on a research article about C.N. Annadurai’s critique of the Kambaramayanam. In the course of my research, I came across your interesting article on this topic published on the website of the Ilankai Tamil Sangam

“Vanakkam! I am a research scholar working on Tamil at the University of Hamburg, Germany. I am currently working on a research article about C.N. Annadurai’s critique of the Kambaramayanam. In the course of my research, I came across your interesting article on this topic published on the website of the Ilankai Tamil Sangam

(http://www.sangam.org/2007/09/Kambar.php). Thank you very much for sharing your views on the topic!

In your article, you are mentioning three rebuttals of Annadurai’s “Kamparasam”. You also state that you have one of these (Kambarasathukku Savumani) in your possession. Since these texts are very hard to come by, I was wondering if you were willing to share a scan of this book with me….”

The last sentence quoted above touched me deeply. This particular booklet, ‘Kambarasathukku Savumani’ [Death-bell to Kambarasam] was an un-dated 32-page rebuttal of Anna’s 1940s polemic, ‘Kambarasam’ [The Taste of Kambar]. I picked this booklet from the collection of one of my deceased elderly kin Mr. V. Govindapillai’s library when I visited Point Pedro more than 40years ago – long before the Sri Lankan army-LTTE conflict began. Apart from losing their lives, Eelam Tamils had lost so many cultural treasures, since the 1981 planned vandalism of Jaffna Public Library by the Sri Lankan armed forces.

As I have reached 62 last week, I felt that there is a need to post the print materials collected by me for the past 40 year or so, for the benefit of Tamil diaspora as well as to the scholars interested in Tamil affairs. Many my paper collections are yellowing, and some of the magazines or newspapers in which the original materials appeared had become defunct for various reasons. But the onslaught of half-baked scholarship on LTTE and Eelam Tamil nationalism fills quite a number of pages in peer-reviewed journals. One appropriate defense to spurious scholarship is to transcribe and post original materials in the electronic media.

To commemorate the defeat of Eelam Tamil nationalism in 2009, time permitting, I plan to do this laborious work at occasional intervals. To begin this series, I provide two items here. Sentences or phrases that appear within parenthesis are as in the original. The spelling of the names of peoples and places appear as they appear in the originals.

Item 1: V. Prabhakaran’s interview to Indian journalist Ms. Anita Pratap, which appeared in the Time magazine (International edition, April 9, 1990). This is a 25th anniversary feature. As I have written previously in many occasions, none of the four star- five star military generals of Sri Lanka or the military deserters like Gotabhaya Rajapaksa could boast of fighting with the Indian army for 30 months. Only Prabhakaran hold this record for leadership in Sri Lanka.

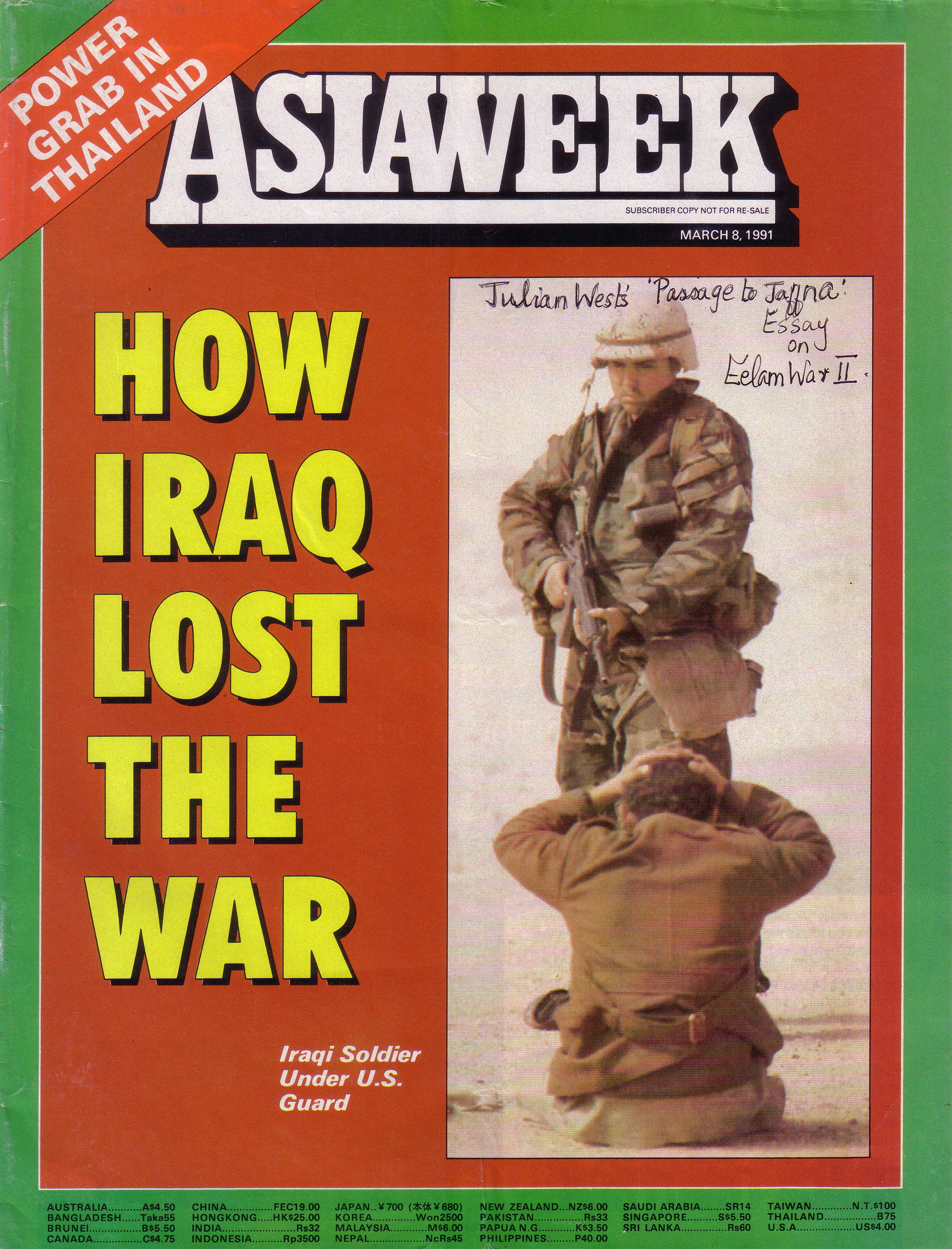

Item 2: Julian West’s essay ‘Passage to Jaffna: Enduring the Agony of Sri Lanka’s War’, which appeared in the Asiaweek (Hongkong) magazine, March 8, 1991. This, 3,100 word essay, I consider as one of the poignant description of Valvettiturai bombing in January 1991, when Americans were engaged in Gulf War crisis with Saddam Hussein. The chief combatant of Prabhakaran was tough-talking Mr. Ranjan Wijeratne, the then Deputy Defense Minister in President Premadasa’s cabinet. He had cautioned Jaffna Tamils, in a press conference, “We don’t want to harm civilians. But they must understand that it is dangerous to live in those areas where the LTTE are operating. They must use their common sense and move out of Jaffna.” Within two months, Mr. Wijeratne lost his life tragically in a well-planned road bombing operation in Colombo. Check the date of Asiaweek magazine’s cover March 8, 1991, scanned nearby. When this issue appeared in the newsstands, Mr. Wijeratne was not among the living (He was killed on March 2, 1991!). Some readers may enjoy the chuckle line in Julian West’s essay about his description of two LTTE Tigress women Malini and Nishanti: “They are shy of me – although they are the ones with the T-81 Chinese assault rifle. Both have received military training and fought the Sri Lankan army in several battles. ”

In 2006, much anti-LTTE propaganda was made by LTTE’s opponents about the banning of LTTE as a terrorist organization by European Union (EU). Uncle Sam’s State Department ambassadors in Colombo were preaching ‘globalization mantra’ and living in unified Sri Lanka as the panacea for Eelam Tamils. The irony of it is that, now in some member countries of EU, separatism has taken a firm root. We hear separatism cries in Scotland (United Kingdom), Belgium and Italy, not to mention Spain. Please refer to the Wikipedia entry ‘List of active separatist movements in Europe’ [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_active_separatist_movements_in_Europe]

This trend indicates that Prabhakaran’s spirit is still alive in other European countries as well.

A Tiger Changes Stripes

[Interview by Anita Pratap: Time, April 9, 1990, pp. 14-15]

For almost two decades the legendary Vilupillai Prabhakaran, 35, has fought for a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka. He battled first the Sri Lankan and now the Indian army to a standstill. Emerging from his jungle hideout for the first time in more than two years, the guerrilla leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam says he is ready for elections.

Q: What made you confront India?

Prabhakaran: India claimed to have intervened in Sri Lanka to secure Tamil interests. In actual fact, India came to secure its own interests. There was never any genuine attempt to understand and solve our problems. India deliberately aggravated Sri Lanka’s ethnic crisis. It destabilized Sri Lanka [by training and arming Tamil militants, including the Tigers] so that it could play a dominant role in bringing Sri Lanka within its sphere of influence.

What I can’t forgive is the way India claimed to have intervened to protect the Tamils and then launched this war against our people. On the third day after the war started, I sent an appeal to India to stop the attack because of the civilian casualties. But India mistook it as a sign of weakness and pressed ahead with the offensive, thinking they could crush us.

Q: But isn’t it true that India has consistently stood for a united Sri Lanka?

Q: But isn’t it true that India has consistently stood for a united Sri Lanka?

Prabhakaran: India used this excuse to impress the world that it was the protector of Sri Lanka. By adopting this line, India ensured that other powers were excluded from interfering in this region.

Q: You knew India was using the Sri Lankan Tamil problem to pursue its interests, but didn’t you also use India by taking advantage of Indian training and arms?

Prabhakaran: Yes, we also used India. We were aware of India’s strategy but made use of the opportunity to strengthen ourselves militarily.

Q: What gave you the courage to take on the world’s third largest army?

Prabhakaran: India failed to secure the release of twelve of my area commanders who were arrested by the Sri Lankan security forces. [When the captives later swallowed cyanide] their suicides made me determined to confront the Indian army. Some of my top colleagues cautioned me against it and wondered how long the LTTE could hold out. I gave them the Viet Nam example – a small nation can fight a superpower with determination and dedication. When I was deciding to fight, the thought of winning or losing didn’t bother me. What you have to assess is whether you have the will to fight. People cannot give up their cause, their rights, for fear of defeat.

Q: Is there a lesson in this for India?

Prabhakaran: That however formidable a military power you may be, you cannot impose upon a people anything against their will.

Q: What guerrilla technique was most useful to you?

Prabhakaran: We used land mines to great effect. They caused a lot of Indian casualties.

Q: What did you consider were the Indian army’s main strengths and weaknesses?

Prabhakaran: Their strength – and their weakness – was their huge manpower. It created difficulties for us. It restricted our mobility. But because they came in large numbers, they suffered many casualties. Also, they wasted a lot of time, energy and money on providing logistical support. Another major weakness was that the Indian army was not motivated. The soldiers didn’t know why they were fighting. They were confused. They came to protect Tamils, and then they had to kill them.

Q: And what in your judgment were the LTTE’s own strengths and weaknesses?

Prabhakaran: Our strength – and our weakness – was our overconfidence. Sometimes our cadres took impossible risks, like ambushing an Indian patrol at a point where there were no escape routes. This cost us casualties. We were sometimes careless. But also because of our overconfidence, our boys carried out some amazingly brave attacks.

Q: The Indians say they fought this war with one hand tied behind their backs because they wanted to minimize civilian casualties.

Prabhakaran: If they could indulge in such atrocities against our people with one hand tied behind their backs, I shudder to imagine what havoc they would have unleashed if both hands had been free. They used every technique – aerial strafing, dropping 250-kg bombs, artillery bombardment, harassment of civilians. These are excuses peddled by a defeated army.

Q: Some 6,000 Tamil civilians were killed in the war with the Indian army. Was it worth it?

Prabhakaran: Yes. We have proved that we will not allow any force to interfere with the freedom and independence of our people.

Q: But what have you gained?

Prabhakaran: I have gained self-confidence, courage and the support of my people.

Q: What made you start negotiations with Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa?

Prabhakaran: Our people thought India would give us Tamil Eelam [a separate Tamil state]. Instead India [reached an agreement] against our will. So we thought it would be better to talk to the Sri Lankan government and work out a better deal. Besides, LTTE will not allow a foreign force to intervene and dominate our people. Premadasa articulated the same viewpoint. He was determined to end the foreign intervention.

Q: Now that the Indian army has gone, many fear that confrontation with the Sri Lankan government – your historical enemy – is again inevitable.

Prabhakaran: We have had a long history of state oppression against our people. Earlier, the Tamils negotiated and were repeatedly betrayed, and so the armed struggle was born. If the Sri Lankan government resorts to state oppression against the Tamils and Muslims, then we will fight. But we hope the current peace will continue.

Q: How sincere do you think Premadasa is about solving the problems of the Tamils?

Prabhakaran: We started the negotiations on the basis of trust. We have that trust.

Q: How serious is the LTTE about participating in the provincial council elections?

Prabhakaran: We are very serious. We want to show India and the world that we are the authentic representatives of the people.

Q: Have you given up the demand for an independent Eelam?

Prabhakaran: We have not.

Q: Then what are you talking to Premadasa for? How can you enter the democratic mainstream if you still cling to your separatist cause?

Prabhakaran: We are entering the political mainstream. Our demand for self-determination will not be an impediment for us to enter the political process.

Q: Many people feel that your peace talks with Premadasa are only a tactical move.

Prabhakaran: We have not cheated or betrayed anybody. At the same time, if we are cheated or betrayed, we will react. But if somebody trusts us, then we will reciprocate.

********

Passage to Jaffna: Enduring the Agony of Sri Lanka’s War

by Julian West [Asiaweek, March 8, 1991, pp. 13-22]

I crawl into a sandy hole in the ground, preceded by a small boy. Hardly able to breathe inside the concrete-walled bunker, sand trickling through the palm-trunk supports above my head, I try to imagine what it must have been like – pressed in here with 30 or 40 freightened people – during the Sri Lankan Air Force bombing raids three weeks earlier.

People sometimes stuff their ears with cotton wool to deaden the sounds of bombardment – described as one of the most frightening aspects of a raid – although the bunkers are almost sound-proof. Barely a few paces away the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean lap noiselessly, sole reminder of the once – timeless beauty of Valveddithurai on Sri Lanka’s northern shore. [Note by Sachi: Mr. West’s geographical knowledge is a bit murky here. Indian Ocean do not reach Valveddithurai shore! What he meant was Palk Strait.]

At midday on Jan.20 an air force helicopter flew over the town, dropping leaflets warning people to move out within 48 hours. Three hours later, as people cowered in bunkers, the first bombers arrived. They were accompanied by helicopter gunships and shelling from Palalai military base, 10 km away. That night, flares from naval vessels offshore lit up the town. Four days of continuous bombardment later, after more than 250 bombs had been dropped, Valveddithurai was virtually reduced to rubble.

Emerging from the bunker, I am greeted by the same desolate scene that shocked survivors. Whole streets are destroyed. Barely a house is left undamaged. Valveddithurai, birthplace of Tiger guerrilla leader Velupillai Prabhakaran and a well-known smuggling area, has been bombed several times during this seven-year war. In the latest attack, 500 houses and two large schools were demolished and more than 100 other buildings, including two historic Hindu temples, were irreparably damaged. A Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) camp less than a kilometer away was untouched.

Valveddithurai was one of the most densely populated towns in Sri Lank. Ten thousand people lived in a 1.6 km coastal strip. The tightly packed houses collapsed on to each other lack a pack of cards. Miraculously, only ten people were killed and 20 seriously injured. Forwarned by the leaflets and the first round of attacks, 90% of the population left for neighbouring villages. The rest hid in bunkers. Almost every house in Jaffna Peninsula has one, which accounts for the relatively low mortality rate in recent bombings.

‘We have been attacked since 1984, so we’re quite used to it,’ says Dr. K. Shanmugasunderam, head of the Valveddithurai Citizens Rehabilitation Committee, who recites statistics of destruction from his ‘mobile office’, a straw shopping bag.

Not much is left of Valveddithurai. A family shifts rubble from the ruins of their home. Another couple with a small child attempt to cook a meal on the square-meter patch of floor that remains of their house. I ask the man what they intend to do. ‘We’re hoping some aid organization will help us rebuild. This is our land and though it’s small, we don’t want to leave it.’

The destruction of the historic Sivam Kovil and Muttiaramman temples, twin Siva and Shakti temples more than 200 years old, has offended the residents deeply. ‘How would you feel if a temple in your area was destroyed?’ asks Dr. Shanmugasunderam. ‘I cannot express it in words. But I feel it in my heart.’ At his insistence we take our shoes off and tiptoe among the broken glass and brick shards carpeting the floor. He informs me that, had a bomb not just desecrated the temple, non-Hindus like myself would not be allowed in.

Valveddithurai people are intensely proud of their seafaring history. They are especially proud of having produced Mr. Prabhakaran, their ‘son’, and are vehemently pro-Tiger. ‘We have not lost our hearts, despite the massive destruction,’ says Dr. Shanmugasunderam. ‘We feel we can stand again. We’re fighting for our freedom and we’ll fight till we reach our objective.’ Ironically almost the only intact edifice is the town fountain – four brightly painted, cartoon-like tigers rampant.

On Jan. 30 air force bombers attacked a crowded market in Pudukudiyiruppu, a village south of Jaffna Peninsula with a 90% refugee population, killing 22 people and seriously wounding thirteen. ‘Three Siai Marchetti bombers swooped down on the market at 5:30 pm – exactly the time most people are there,’ says an observer. ‘A child had to have both legs amputated. Later we found an arm. Pudukudiyiruppu was a precise target. There were no LTTE nearby.’

Throughout the night patients were relayed to Jaffna General Hospital by the Red Cross and the Tigers, a five-hour journey along cratered dirt roads and by ferry. In the casualty ward, a man with the saddest eyes I have ever seen tells me he has lost his wife in the raid, leaving him with their seven-year-old son.

The same week a refugee camp housing 40 families in a girls’ school, 10 km from Jaffna town, was also bombed. Two people were killed and four wounded. A fourteen-year-old girl lost her leg. On the road south, at an ancient shrine to the Hindu elephant god, Ganesh, bombs killed a man, his baby daughter and a ten-year-old boy.

Bombing raids on the north have intensified since Jan. 10, the end of a Tiger-proposed ten-day ceasefire. The LTTE was beleaguered by bad weather, adverse international opinion and a crackdown on its activities in India’s Tamil Nadu State. The army, believing the Tigers were weakening, did not want the ceasefire. ‘Strategically that was the time to hit them,’ says a colonel in the northern command.

Outside observers believe the intensity of the present campaign signals two things. ‘Under the cover of the Gulf Crisis,’ says a Tamil lawyer, ‘the armed forces are engaging in military operations of an indiscriminate and reckless nature.’ The other indication is that the army is working to a deadline, which some observers think may be June this year. North of Vavuniya, a town 140 km south of Jaffna, Sri Lankan forces hold only Palalai air base, Elephant Pass and Kankesanthurai naval base. They have therefore resorted to aerial strikes – most damaging to civilians.

The army claims it only bombs known Tiger targets. But it admits that its aircraft – single-engine Siai Marchetti training planes, adapted to carry two bombs; Chinese Y-8s and Y-12s; and British Avros, small passenger planes from which homemade bombs are pushed out – do not permit accuracy. ‘We do not have the sort of equipment the Americans have,’ says an army spokesman. ‘Ours is just a ‘look and see’ operation. However we sometimes wonder if it’s worth killing civilians just to get 20 terrorists.’

The bombs – oil drums with gelignite or sometimes inflammable gas and rubber tyes, which stick to the skin like napalm – have no ballistic stability. ‘If you look up you can see them twisting and turning as they fall’, says the colonel. ‘Sometimes we ourselves are mortally afraid of where they’re going to land.’ The forces accidentally bombed two of their own men recently.

Infiltration of the Tigers among civilians also creates inevitable casualties. ‘The LTTE has taken over so many houses, if the Sri Lankan government wants to bomb them, it will have to bomb the whole peninsula,’ says an exiled Tamil MP in Colombo. Deputy Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne told a recent press conference: ‘We don’t want to harm civilians. But they must understand that it is dangerous to live in those areas where the LTTE are operating. They must use their common sense and move out of Jaffna.’

I have come to Jaffna by accident – perhaps the best word to describe a 280 km journey across battle lines and through a free-fire zone. I had intended to branch off westward. But once through the Sri Lankan army checkpoint, I keep going up the long road north. To deter attacks from helicopter gunships or stray bombers, I paste a banner reading PRESS in large letters across the roof of the car. And hope for the best. Journalists have no permission to visit Jaffna.

Past the Sri Lankan army checkpoint at Vavuniya, I enter a 1.6 km no-man’s land before the Tiger checkpoint. About 3,000 people are waiting in line, bound for Colombo. Many have waited five or six days. It is midday. There is no shade. The temperature is in the 30s.

Each morning around 8:30 people run from the Tiger checkpoint to queue at the army checkpoint. Each afternoon most are sent back. I am told the army is processing an average of ten people a day. Meanwhile these people, who have already made an arduous two- or three-day journey to Vavuniya, have to sleep out or under trucks, sometimes in the rain. They have no food and are at the mercy of bicyle vendors selling rice packets at four times the normal price. There is no water, no lavatory. ‘Now you see what we, as a minority, have to go through,’ says a salesman.

‘Conditions here are inhuman,’ says Mr. Kulasekeram, a thin, middle-aged clerk in the Land Commission Department, returning from a visit to his family. He whispers to me: ‘Some ladies have not urinated for two or three days.’ A man with throat cancer is going to hospital in Colombo. Later, I discover, a heart patient who waited at the checkpoint for five days has died.

I last visited Jaffna seventeen years ago. Then, as now, it seemed another country – separated from the rest of Sri Lanka not only by a causeway across a lagoon, but by language, culture, religion and vegetation. Jaffna is an arid, hot, sandy spit of land where brittle palmyra trees stand sentinel against a burning sky, like huge fans. At night, in the dry atmosphere, the sky is brilliant with stars.

Jaffna people – Tamil-speaking Hindus – have been conditioned by their sparse environment. They are hard-working and thrifty, with a high percentage of doctors, lawyers and engineers. Geographically and culturally the people of Jaffna are closer to south India. Valveddithurai is only 30 km from Tamil Nadu, half the distance to the nearest Sinhalese town. Their isolation from the mainly Buddhist south was entrenched by a Sinhala-only language policy, introduced in the 1950s, designed to favour a Sinhalese work-force. That confirmed their minority status – they comprise 18% of the island’s 17 million population – and germinated the present separatist war.

As a Jaffna religious leader explains: ‘Under the British we were all equal. They found Tamils hard-working and dependable, which is why there were so many English schools in Jaffna – for employment. After the British left, our youth found no avenue of employment. The only work here is coastal fishing or farming.’

Then, Jaffna society seemed conservative and strict, caste-bound and enclosed. Young people were brought up to study. Girls were kept indoors, in the kitchen, until marriage.

I find Jaffna changed forever. The palmyra trees and sandy wastes are still here. But in the last seven months an estimated 20,000 buildings in the peninsula have been wholly or partly destroyed. The walls of those left standing are cracked, ceilings have collapsed, barely a window pane remains.

A shortage of petrol and its prohibitive cost – $10 a litre, thirteen times more than in the south – has grounded the black Austin A40s and Morris Minors that once chugged solidly down the Jaffna lanes. Now a relay of bicycles ferries kerosene and other essentials the 280-km round trip from Vavuniya. Women, dressed as if for a wedding in astonishing red and gold saris, perch on the crossbars of bicycles, like birds of paradise, bound for destinations kilometers away. Only the Tigers drive vehicles.

After sunset most houses are in darkness. Kerosene costs ten times the Colombo price and matches are unavailable. ‘We have been in the dark for the last ten months,’ says Mr. Kulasekeram. ‘Our children can’t study anymore.’ There is no firewood or gas for cooking. Cash is short: banks receive insufficient money for their needs. Telephone lines were cut long ago.

Less than a third of the food needed by Jaffna arrives. Lorries are detained at Vavuniya for months, waiting for transport permits. An official says only 3% of food intended for the area has been delivered in the past three months. ‘People are on the brink of starvation,’ he says. ‘They’re dying in silence.’ Food sent by the government from Colombo by ship, under the Red Cross flag, often returns unloaded because of high seas or attacks around the military camp at Palalai.

Once a ship arrived packed with sanitary towels. ‘There were thousands of sanitary towels in Jaffna,’ confided a nun. ‘We don’t need sanitary towels, we need food. People are living on one meal a day.’

In the airy, rambling Jaffna General Hospital, a doctor tells me they lack essential drugs, dressings and surgical instruments. ‘Operations are often delayed because of lack of oxygen,’ he says. ‘Also, we don’t have enough oxygen for follow-ups, so some people die.’ Half the 1,015 beds cannot be used because of bomb damage.

The face of society, too, has changed. Most of the middle class and professionals have emigrated to Canada or Australia. Since last June 125,000 refugees have gone to Tamil Nadu – swelling the number there to 200,000. More Tamils now live in Greater London – 60,000 – than in Colombo. In the peninsula 250,000 are displaced.

Most astonishing of all to some older Tamils is the emergence of a young guerrilla movement – the Tigers. ‘No one was as shocked as we were when our boys went to war,’ says a Tamil government servant. ‘The traditional set-up of our society has changed.’ Notes a Tamil lawyer in Colombo: ‘The under-35s now constitute the ruling class.’ As Mr. Anton Balasingham, the LTTE’s amiable political spokesman, says: ‘We are running the law and order here. We are the civil administration.’

At the LTTE’s administrative offices, people wait to have domestic and land disputes settled and to get exit permits to leave the north. Armed cadres stroll in and out, but the atmosphere is relaxed. Small uniformed boys run errands, though the office is also staffed by dedicated civilians. ‘It’s very difficult for us to live now,’ says Sarojini, a 38-year old woman in a blue sari, who works as a translator and whose fourteen-year-old son is a cadre. ‘But we don’t care about the food. We want freedom.’

In a real sense, the LTTE is like a large family. Many Jaffna people have relatives in the Tigers, and call them ‘our boys’. Their monkish disciplines are admirable, if austere: no smoking, no drinking, no marriage until a certain age and number of years of service. They have revolutionized the role of women in Jaffna, giving them equality, as fighters, and striving to eliminate dowry and caste systems.

Malini and Nishanti, tiny but stocky Tigresses, represent the new Jaffna woman. Wearing combat fatigues, their hair tied up in braids – the regulation Tigress hairstyle – two two area leaders giggle, hold hands and clasp each other’s knees as we wheel down the road in a trishaw. They are shy of me – although they are the ones with the T-81 Chinese assault rifle.

Both have received military training and fought the Sri Lankan army in several battles. Initially, they explain, girls were involved in political work, but six years ago they insisted women be allowed to fight. They were first given AK-47 and M-16 assault rifles. Later they carried heavy weapons like rocket-propelled grenade launchers, bazookas and machine guns.

Malini says she and fourteen other women halted the advance of Indian Peacekeeping Force troops on Jaffna town in October 1987. ‘We didn’t have uniforms then, so we were wearing skirts and blouses. The Indians didn’t notice us, although we were carrying guns. They thought we were just a group of young girls. I ordered the girls to lie down and from there we started firing.’

Malini, 28, is postponing marriage. ‘Getting married and having children is not a problem. But so many of my sisters have died so I have a responsibility to continue the struggle.’ So far 106 women Tigers have died in the war.

Nishanti, 22, joined the LTTE in 1987. Like many Tigresses she ran away from home to join, knowing her parents would stop her. They had hoped she would go to university. ‘I joined not to fight against the enemy but to liberate myself,’ says Nishanti. ‘I’m opposed to the dowry system. Now I wouldn’t accept a man who wanted a dowry. Although Tamil women can choose to work and be free, all these aspirations come to nothing in the end. Women are enslaved by traditional systems and male chauvinism.’ As women guerillas, they experience unheard-of freedom.

Yet the Tigers’ domination of Jaffna society, often through fear – real and imagined – gives them a sinister complexion. More than once I’m told I cannot photograph a poster or a hospital ward without ‘permission’. Jaffna now has no political parties, no trade unions, no non-governmental organisations. Newspapers are controlled. ‘It has become a society with no political freedom,’ says a Colombo Tamil professor. ‘The intelligentsia, formerly an important component of society, has been subjugated.’

Still, support for the Tigers in Jaffna seems genuine, even fierce. Indiscriminate bombings and an economic blockade on the north have inevitably driven people into the Tigers’ arms. ‘Young people are still joining the LTTE,’ says the exiled politician. ‘They feel if they are going to die anyway in bombing raids, they might as well fight for their rights.’ Adds the lawyer: ‘I don’t see how the government can ever win back the confifence of people who feel so alienated. People from Jaffna feel the government has crossed a certain moral threshold which forfeits its right to claim the allegiance of those citizens.’

Meanwhile combat continues. The week after my visit Minister Wijeratne declared: ‘We’re fighting a war and we’re fighting it to a finish.’ Mr. Balasingham claims the LTTE would prefer ‘a political solution to a political problem.’ But with its leader, Mr. Prabhakaran, in the role of jungle fighter and hero, and with an entire generation of Tamil youth indoctrinated as guerillas or sympathetic to the Tiger cause, the leap from warfare to politics looks impossible. Mr. Balasingham says there is ‘now no alternative but to fight for an independent state.’

‘The civilian population is fed up with this war,’ says a Tamil observer. ‘But there is no space for them to speak out. There are very few rational voices. The situation is so dismal, one hardly sees any light at the end of the tunnel. It’s like a bad dream.’ Replies the army colonel when I ask him how long this war might last: ‘I think foreign correspondents can expect work in Sri Lanka for a long time.’

*******

“History is always written by the winners. When two cultures clash, the loser is obliterated, and the winner writes the history books-books which glorify their own cause and disparage the conquered foe. As Napoleon once said, ‘What is history, but a fable agreed upon?”

― Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code

My hearty thanks to Dr. Sachi for his noble mission which is very timely considering the fact that winners write history, it is the need of the hour wherein we go through a phase of temporary setback. Our future generations need reliable sources to learn the unbiased history.

[…] From Sachi’s Files – Chapter 1 by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 17, 2015 […]

History authorises the victory and glosses over the means in which the winner achieves victory. History is a construct; a perception; and the folly is that it repeats itself. Hope Sachi will not trip over the wires of folly!

Thought of correspondent Haifu is well received. I’d add that history is also foggy. I’d try my best to bring some clarity.