Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

The Anglo-Boer Warsby Boer-War.com, accessed March 6, 2007

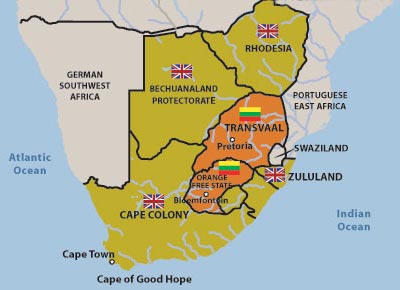

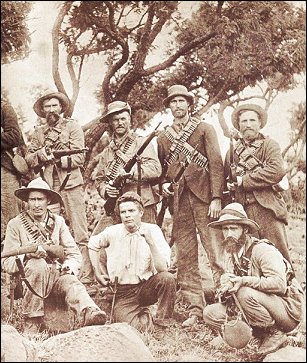

The First Boer War The first clash was precipitated by Sir Theophilus Shepstone who annexed the Transvaal (the South African Republic) for the British in 1877 after the Anglo-Zulu War. The Boers protested and in 1880 revolted. The Boers dressed in earthtone khaki clothes, whereas the British uniforms were bright red, a stark contrast to the African landscape, which enabled the Boers to easily snipe British troops from a distance. After a British force under George Pomeroy-Collery was heavily defeated at the Battle of Majuba Hill in February 1881 the British government of Gladstone gave the Boers self-government in the Transvaal under a theoretical British oversight. The Second Boer War

There was continued pressure on the Boers, as following the discovery of gold in the Transvaal in 1885 at Witwatersrand Reef there was a rush of non-Boer settlers, uitlanders. The new settlers were poorly regarded by the Boers and in return there was pressure to remove their government. In 1896 Cecil Rhodes sponsored the ineffective coup d'etat of the Jameson Raid and the failure to gain improved rights for Britons was used as an excuse to justify a major military buildup in the Cape. There was another reason for the British intention to take control of the Boer Republics: there was at the time an attempt made by the Transvaal Republic to link up with German South West Africa, a possibility which the British, with an eye to the coming clash with the Empire of the Germans, determined to thwart. The Boers, under Paul Kruger, struck first. The Boers attacked into Cape Colony and Natal between October 1899 and January 1900. The Boers were able to successfully besiege the British garrisons in the towns of Ladysmith, Mafeking (defended by troops headed by Robert Baden-Powell) and Kimberley and inflicted three separate defeats on the British in one week, December 10 to 15, 1899. It was not until reinforcements arrived on February 14, 1900 that British troops commanded by Lord Roberts could launch counter-offences to relieve the garrisons (the relief of Mafeking on May 18, 1900 provoked riotous celebrations in England) and enabled the British to take Bloemfontein on March 13 and the Boer capital, Pretoria, on June 5. Boer units fought for two more years as guerrillas, the British, now under the command of Lord Kitchener, responded by constructing blockhouses, destroying farms and confiscating food to prevent them from falling into Boer hands and placing Boer civilians in concentration camps. The last of the Boers surrendered in May 1902 and the war ended with the Treaty of Vereeniging in the same month. 22,000 British troops had died and over 25,000 Boer civilians. The treaty ended the existence of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as Boer republics and placed them within the British Empire. But the Boers were given £3m in compensation and were promised self-government in time (the Union of South Africa was established in 1910). The Boers referred to the two wars as the Freedom Wars. Concentration Camps

These camps had were originally set up for refugees whose farms had been destroyed by the British "Scorched Earth" policy (the burning down all Boer homesteads and farms to stop the aid of Boers). Then, following Kitchener's new policy, many women and children were forcibly moved to prevent the Boers from re-supplying from their homes and more camps were built and converted to prisons. This relatively new idea was essentially humane in its planning in London but ultimately proved brutal due to its lack of proper implementation. This was not the first appearance of concentration camps. The Spanish used them in the Ten Years' War that later led to the Spanish-American War, and the United States used them to devastate guerrilla forces during the Philippine-American War. But the concentration camp system of the British was on a much larger scale. There were a total of 45 tented camps built for Boer internees and 64 for black African ones. Of the 28,000 Boer men captured as prisoners of war, 25,630 were sent overseas. So, most Boers remaining in the local camps were women and children, but the native African ones held large numbers of men as well. Even when forcibly removed from Boer areas, the black Africans were not considered to be hostile to the British, and provided a paid labour force. A delegate of the South African Women and Children's Distress Fund, Emily Hobhouse, did much to publicise the distress of the inmates on her return to Britain after visiting some of the camps in the Orange Free State. Her fifteen-page report caused uproar, and led to a government commission, the Fawcett Commission, visiting camps from August to December 1901 which confirmed her report. They were highly critical of the running of the camps and made numerous recommendations, for example improvements in diet and provision of proper medical facilities. By February 1902 the annual death-rate dropped to 6.9% and eventually to 2%. |

|||||

|

||||||

There were two Boer wars, one ran from 16 December 1880 - 23 March 1881 and the second from 9 October 1899 - 31 May 1902 both between the British and the settlers of Dutch origin (called Boere, Afrikaners or Voortrekkers) who lived in South Africa. These wars put an end to the two independent republics that they had founded.

There were two Boer wars, one ran from 16 December 1880 - 23 March 1881 and the second from 9 October 1899 - 31 May 1902 both between the British and the settlers of Dutch origin (called Boere, Afrikaners or Voortrekkers) who lived in South Africa. These wars put an end to the two independent republics that they had founded.

The conditions in the camps were very unhealthy and the food rations were meager. The wives and children of men who were still fighting were given smaller rations than others. The poor diet and inadequate hygiene led to endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery. Coupled with a shortage of medical facilities, this led to large numbers of deaths — a report after the war concluded that 27,927 Boers (of whom 22,074 were children under 16) and 14,154 black Africans had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all, about 25% of the Boer inmates and 12% of the black African ones died (although recent research suggests that the black African deaths were underestimated and may have actually been around 20,000).

The conditions in the camps were very unhealthy and the food rations were meager. The wives and children of men who were still fighting were given smaller rations than others. The poor diet and inadequate hygiene led to endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery. Coupled with a shortage of medical facilities, this led to large numbers of deaths — a report after the war concluded that 27,927 Boers (of whom 22,074 were children under 16) and 14,154 black Africans had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all, about 25% of the Boer inmates and 12% of the black African ones died (although recent research suggests that the black African deaths were underestimated and may have actually been around 20,000).