Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

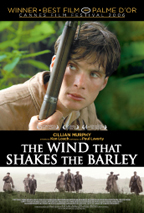

History, Bloody Historyby A.O. Scott, The New York Times, March 16, 2007

But in watching ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley,'' his new film (which won the top prize at Cannes last year), it is possible to appreciate both Mr. Loach's passion and his sense of nuance. Set in Ireland in the 1920s, the film paints history in stark colors and observes as they blur and bleed. Mr. Loach and Paul Laverty, the gifted screenwriter with whom he regularly collaborates, leave no doubt as to who the villains are in this tale. From the start, when they raid an Irish farm, the British irregulars known as the Black and Tans are as brutal and sadistic as Hollywood Nazis. The atrocities they commit have an immediate radicalizing effect on the film's hero, Damien (Cillian Murphy), who abandons his plans to study medicine in London to join the armed uprising against the British. Injustice, in Mr. Loach's world, tends to be a simple matter. It resides in the unprincipled, dehumanizing exercise of power -- whether wielded by capital, the state, or an army of occupation -- against those who have none. The complications arise, and the arguments start, when the powerless try to fight back. Brutal as ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley'' is in depicting British acts of violence, it does not flinch from showing the harsh, sometimes heartless tactics of the Irish Republican Army flying columns. Among the most painful scenes are the executions of an informer and later a landlord, killings that foreshadow a turn from insurrection to civil war. Radical though he is, Mr. Loach is hardly a romantic, and the deep humanism that informs his best work -- a category in which ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley'' surely belongs -- is insulated from sentimentality by the sense that history is a long, bruising fight, a chronicle of compromise and defeat as well as of tentative triumph and provisional hope. He is also, as anyone steeped in the history of the modern left must be, acquainted with the factionalism and disunity that bedevils those who see themselves on the side of the angels. ''Land and Freedom'' (1995) examined this theme in the context of the Spanish Civil War, in which anarchists and communists at times fought each other as fiercely as they fought Franco. The logic of rebellion in ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley'' has a similarly grim implacability. You start out fighting an obvious, odious enemy, and you will end up killing your friends. It's an old story perhaps, but Mr. Loach and Mr. Laverty tell it with enthralling -- and devastating -- economy and force. Beauty too. Mr. Loach and his cinematographer, Barry Ackroyd, use the grays and greens of the cloud-cloaked Irish countryside as a moody palette. Sometimes the human figures stand out in bold relief against the flat sky; at other moments they are wrapped in fog and smoke. Mr. Loach has always populated his films with superb actors (his knack for discovering them is uncanny), and the quality of the performances he elicits serves as a check against his more schematic polemical impulses. Mr. Murphy, fine-boned and ferocious, gives Damien a gentleness and sensitivity that shades toward fanaticism. He is a purist, an idealist, and therefore marked for a tragic destiny, either as monster or martyr. His performance is perfectly complemented by that of Padraic Delaney, who plays Damien's brother Teddy, a brave soldier but also a fatefully pragmatic politician. Between them is the marvelous Orla Fitzgerald as Sinead, a perfectly believable incarnation of an indomitable Irish woman. In 1921, after several years of fierce fighting, the Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State, an event that split the Republican movement and unleashed a period of factional bloodletting, the Irish Civil War. The consequences of this strife propel ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley'' through its terrible final act, which is all the more chilling for being dramatized with such precision. Afterward it comes almost as a shock to recall that the Republic of Ireland today is a prosperous member of the European Union, and that even the Northern Ireland seems to have moved beyond sectarian violence. But the history presented in ''The Wind That Shakes the Barley'' hardly feels like a closed book or a museum display. It is as alive and as troubling as anything on the evening news, though far more thoughtful and beautiful.

| ||

In Ken Loach's movies -- he has made more than 20 in the last 40 years -- characters frequently argue about politics, which is only fitting, since the films themselves are political arguments. There is no point in combing through Mr. Loach's work for hints of ideological significance. Ideology -- Marxist, anti-imperialist, aligned with the perceived interests of the powerless and the marginal -- is the engine that drives his stories. The clarity and force of those stories is considerable, but their bluntness sometimes sticks in the craw of critics, who often scold Mr. Loach for lacking subtlety.

In Ken Loach's movies -- he has made more than 20 in the last 40 years -- characters frequently argue about politics, which is only fitting, since the films themselves are political arguments. There is no point in combing through Mr. Loach's work for hints of ideological significance. Ideology -- Marxist, anti-imperialist, aligned with the perceived interests of the powerless and the marginal -- is the engine that drives his stories. The clarity and force of those stories is considerable, but their bluntness sometimes sticks in the craw of critics, who often scold Mr. Loach for lacking subtlety.