Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

The Forgotten Landby Rukshan Fernando, The Sunday Leader, April 29, 2007

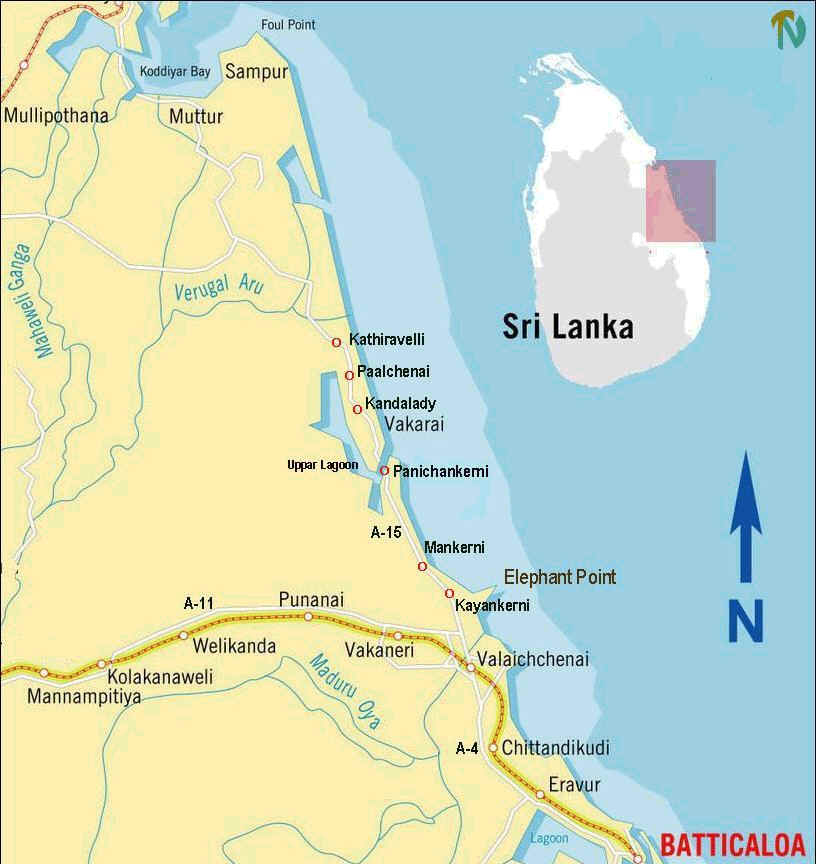

The road to Batticaloa from Colombo seemed longer and more arduous than it was a few years ago. I felt sorry to see the military personnel standing in the scorching sun on the main road between Welikanda and Batticaloa at regular intervals; but they were also a chilling reminder of the undeclared war going on. Long lines of vehicles and people at checkpoints manifest the fears of security forces of a sudden attack, while for the Tamil youth, the checkpoints posed the fear of being arrested on suspicion under the emergency regulations. In most camps, tents and some basic temporary shelter have been provided, and water and latrines were available. Rations were also being provided, although irrationally in some cases. Some government servants, such as grama sevakas, as well as NGOs, UN agencies and some enthusiastic and committed military officials seemed active and overstretched in providing assistance to displaced people. One man from Muttur, who is at the Palameenmadu camp, asked us to intervene with authorities to get "permission" for them to go back, as they didn't have any means of livelihood. "Our children ask for ice chocks and want to eat fish; but we have no money to buy them," he said. Another displaced man in the Satharakondan 1 camp, also from Muttur, said that they were pawning the only belongings they had, like gold chains, to find money. Appalling conditions At the Sathorakondan 1 camp, provisions were also not distributed based on the number of children and the age of the children, and thus, families with a large number of children and with older children, were facing food shortages. In one camp visited by our team, lunch consisting of rice and pumpkin curry was served at 5 p.m with no signs of any dinner. Tough conditions About 200 families from Vakaneri are located in tents on individual plots in a site at Alankulam, on the main road to Batticaloa from Welikanda. According to reports we received, this land belongs to Muslims, and the local Muslims reportedly had distributed leaflets asking the displaced to leave. The displaced people seem to have the support of the Karuna Group, who had asked them not to move out, and poor people seemed to be caught in between the groups. Vulnerable to recruitment Children at Sathorakondan camp have to walk about three miles to get to the school. We visited the camp the evening before schools were expected to reopen and learnt that children above 15 years have not been provided uniforms. Another man in Panichchankerni, near Vaharai, told us that his children will not be going to school, as the school has been damaged and he thought his children couldn't possibly walk the six miles up and down daily to a school in Vaharai. One and half days was enough for me to see several young boys with guns. It was evident to me that gun totting children (and men) were all over the town. Restrictions removed Military officials we met seemed keen on providing as much assistance as possible to the people who had returned, and seemed to be coordinating the provision of rations to people. The hospital, damaged in the recent fighting, had also started functioning. But all was not rosy in Vaharai. On the way to Vaharai, we saw people living in tents and in damaged houses around Panchenkerni. Some of them told us they had not been getting rations in the same manner as people in Vaharai. Military presense A colleague who was taking photos of the Kadiraveli school, which had been damaged by shelling was asked by the military why he was taking photos. Double standards with regard to journalists was clearly visible - a journalist from a leading English daily had been refused permission, while another journalist, who I saw travelling on the back of an army pick up, told me that he had always had access to Vaharai. Ominous sign On the way to Vaharai, on both sides of the narrow road, we saw more people living in tents, in some cases, close to their shattered houses. In Vaharai, I saw an abandoned office of EHED Batticaloa, while on the bank of the Verugal River, I saw a pre school which had been built by EHED Batticaloa, both of which are occupied by the military now. Almost all displaced we spoke to had fears of going back to damaged houses, having had their property looted and means of livelihood such as fishing gear and harvests destroyed. But everyone told us they want to go back to their own village, but they will only go back when their safety and security are guaranteed. Retaliation against civilians Another woman told us that when her 28 year old nephew and some other young men had gone back to Muttur at the request of security forces, they had been arrested in the middle of the night within a church premises, detained and tortured and had been released on bail due to the efforts of church leaders. In one camp in Arayampathy, we received a report of the arrest of a young male IDP by the STF on suspicion of him being a LTTE cadre, when he had returned to his village in Kokkadichcholai in order to check on the safety of his belongings. Humanitarian workers fear another round of forced resettlements, particularly to Eechilampathu and Vavunathivu. Sense of helplessness There is no doubt Batticaloa is facing a humanitarian crisis of gigantic proportions. The government is doing something, but clearly falling way short of its responsibilities. UN agencies, NGOs and church groups seem to be doing their best, but the prevailing atmosphere of hostilities and threats to humanitarian workers doesn't help them. Most people had no resources to visit an office in town, did not know where and how to lodge a complaint. The Human Rights Commission must come forward more proactively to play a protective role, in particular, to inquire into disappearances and abductions and undertake visits to places of detection, and putting in place mechanisms to ensure that human rights assistance is available and accessible to the persons concerned, including those in camps. What is also shocking is the apathy being shown by Sri Lankans in the rest of the country to this huge humanitarian and human rights crisis that has unfolded in the east. --------------------------------

|

||

|

|||