Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by Sachi Sri Kantha

|

Long stretches of the narrow island of Mannar look like Vietnam did 15 years ago, after defoliation by American napalm. Many groves of palmyrah and coconut palm lie black and charred; others have been attacked with saws and cleared. The Sri Lankan government claims that the palm forests are routinely cleared this way every year. But the civilians of Mannar say that the Sri Lankan army, engaged in a harsh and often arbitrary campaign of terror here in the north, is bent on transforming all of the island into a huge sand dune so that it can establish a defence frontline and deprive ‘the boys’ – the Tamil terrorists – of cover. Mannar is 22 miles from India where six Tamil separatist groups have established training camps. Hope is in short supply on the island especially in the predominantly Tamil north, as the battle between ‘the boys’ and the ill-disciplined army slide into civil war. Civilians live in constant fear. More than 160 have been killed in Mannar district by rampaging security forces since December 4. As the excesses of the largely Sinhalese army continue, the lines between the community which it represents – the 75% of the island’s population who are Buddhist Sinhalese – and the 20% who are Hindu or Christian Tamils, appear irrevocably drawn. Every village on the way to Mannar has burned-out homes and shops. A hospital lay in ruins. Nervous, arrogant soldiers dragged passengers from trucks and buses in their search for weapons... We saw evidence of the massacre of December 4 all around us. It began early in the morning when three army jeeps hit a landmine. One soldier was killed and three were injured. Thirty soldiers then went on a six-hour rampage around Mannar. They attacked the central hospital, stopped vehicles and shot the occupants dead on the spot. They lined up 15 employees of a post office and killed eight. They opened fire on peasants in fields, attacked a convent and stripped nuns of watches, gold crucifixes and chains. At the end, nearly 150 people lay dead; 20 are still missing, mostly young male Tamils taken to army camps.

|

Twenty two years have passed since the ‘Anuradhapura Massacre’ of May 14, 1985, in which LTTE killed a total of 146 Sinhalese men, women and children, for the first time in a location beyond the boundaries of Tamil homeland. This aggression has been identified as a paradigm shifting event in recent Eelam Tamil history, which signaled to the world for the first time that the (1) the Sri Lankan parliament’s legislative role in providing a pragmatic solution for the Sinhala-Tamil conflict had lost its value; and (2) the run-of-the mill Sinhalese politicians trapped to their tub-thumping oratory faced a new generation of daring Tamil militant leadership which hardly bothered about oral pyrotechnics.

What those who write today about this massacre in 1985 forget to relate are its precedents in a brutal military campaign against the mostly Tamil-speaking civilian population of the Mannar region.

Time magazine, in a hastily written article notable for its incomplete details in various aspects, covered the Anuradhapura Massacre as follows in 395 words; the author byline was missing.

Tamil Terror: Blood flows at a Buddhist Shrine

[Time magazine, May 27, 1985]

Sri Lanka seemed gripped by madness last week as a series of violent attacks resulted in the slaughter of more than 200 people. The killings began when separatist guerrillas belonging to the country’s predominantly Hindu Tamil minority hijacked a bus and headed for Anuradhapura, a city largely inhabited by Buddhist Sinhalese. As the guerrillas drove into the city’s crowded main bus station, they opened fire with automatic weapons, killing about 100 men, women and children. Then they drove to the Sri Maha Bodhiya, a sacred Buddhist site, and fired indiscriminately into a crowd that included nuns and monks. The rebels continued on to Sri Lanka’s northwest coast, attacking a police station and a game sanctuary on the way, and may have escaped by boat to India, where the Tamil Nadu state is home to 50 million Tamils. The macabre ride resulted in the massacre of 146 people.

By attacking the Sri Maha Bodhiya, the site of a sacred 2,200-year old bo tree said to have grown from a sapling of the tree under which Buddha found enlightenment, the guerrillas seemed almost eager to provoke retaliation. It did not take long. In the bloodiest strike, assailants boarded a ferry off the northern coast of Sri Lanka, near Jaffna, and hacked 39 Tamils to death with axes, swords and knives. The Sri Lankan navy has denied accusations that it was involved in the slaughter; the same day, police surprised Tamil rebels hiding in a cave in the Eastern province and killed 20 guerrillas.

The week’s death list was evidence of the growing struggle between the island’s 2.6 million Tamils and its 11 million Sinhalese. Over the past two years Tamil guerrillas have stepped up their attacks on troops in an effort to force the government into granting them an independent homeland. The Tamils claim that in the 27 years since Sri Lanka achieved independence from Britain, their political rights have been gradually eroded by the Sinhalese majority. Last week’s Tamil rampage through Anuradhapura was the guerrilla’s first major attack on unarmed civilians.

As the violence becomes more widespread, the country is growing increasingly angry at the government of President J.R.Jayawardene, who seems paralyzed by the rebel challenge. Indeed, at week’s end Jayawardene, who is both the Defense Minister and the Commander in Chief of the armed forces, had not even visited the site of the Anuradhapura massacre.

Mannar Massacres by the Sri Lankan Army

The Time report missed some important aspects of the incident.

First, the “separatist guerrillas” were not identified by organizational name. In 1985, the international newsmedia, including Time magazine, couldn’t identify LTTE clearly from its rival claimants who also angled for recognition as Eelam Tamil separatist guerrillas.

Secondly, details about how many “guerrillas” were there in that hijacked bus which “headed for Anuradhapura” were missing.

Thirdly, who led the ‘attack force’ was not stated. Later it came to be known that the leader of that Tamil guerrilla operation in May 1985 was not a Hindu, but a Catholic Christian – Lieut. Col. Victor (Marcelline Fiyuslas, from Panankattikoddu, Mannar) the then LTTE commander of Mannar zone. Eighteen months later, Lieut.Col. Victor attained martyrdom in the battlefield in Adampan, Mannar, on October 12, 1986. As per a profile which appeared in the LTTE’s official organ ‘Viduthalai Puligal’ [Issue 11, November 1986, p. 4] Victor was aged only 23 at the time of his martyrdom. I provide this information for the benefit of academics like Prof. Robert Pape of the University of Chicago, who feel somewhat reluctant to face the truth that there have been/are Christian leaders and Black Tigers in the LTTE.

|

| Lieut.Col.Victor (1963-1986) |

Fourthly, though the anonymous scribe for Time magazine had slanted the report with the spin that the Tamil guerrillas had conducted the Anuradhapura raid “to provoke retaliation” by the Sinhalese, facts recorded by other reporters and commentators during the first four months of 1985 noted the opposite.

Even now, in almost all the recorded retellingz of this Anuradhapura massacre in books and websites, the Sinhalese-slanted version of what appeared in Time magazine in 1985, is regurgitated. But, what in the first place would have given the impetus for the LTTE’s then commander of the Mannar zone, Lieut. Col. Victor, to ‘attack Anuradhapura’ has not been described.

When studying the randomly scattered published reports prior to May 14, 1985, one would be blind to not see a pattern to the Sri Lankan army’s targeted destruction of the serenity and livelihood of the Mannar region and the hapless state in which the predominantly Tamil-speaking Hindus, Christians and Muslims were placed during the second half of 1984 and the first four months of 1985.

I provide below the transcribed texts of five news reports/commentaries pertaining to this period in chronological sequence. Among these five reports, four had the bylines of Mary Anne Weaver, Michael Hamlyn, Steven Weisman and K.P. Sunil. The Economist magazine, as per its editorial policy, didn’t identify its correspondent; though in all probabilities the contributor appears to be Mervyn de Silva, who was the Economist correspondent in Colombo. While Weaver, Hamlyn and Sunil have specifically addressed the plight of the Tamil residents in the Mannar region, Weisman provided a more balanced summary of the then tense situation in the Tamil homeland of the island than the anonymous Economist correspondent.

(1) ‘Tamils hit by scorched-earth blitz’ by Mary Anne Weaver [Sunday Times, London, January 27, 1985, p.9]

(2) ‘Gloves off’ by the anonymous correspondent [Economist magazine, February 9, 1985]

(3) ‘Letter from Sri Lanka: Finding a safe way in rough country’ by Michael Hamlyn [London Times, February 15, 1985, p.32]

(4) ‘A Centuries-Old Struggle Keeps Sri Lanka on Edge’ by Steven R. Weisman [New York Times, February 17, 1985]

(5) ‘Exodus’ by K.P. Sunil [Illustrated Weekly of India, March 24, 1985, pp.14-17]

Among these five, Indian journalist K.P. Sunil’s account on the eyewitness descriptions of Tamil victims of the Sri Lankan army atrocities in the Mannar region was mind-boggling, if that is the appropriate phrase for the outrageous savagery of devilish minds; Tamil teenage boys and even a pregnant mother and her fetus tortured and killed by (1) eye gouging with the serrated edges of a broken bottle (2) killing alive by bundling the victims in gunning bags and setting fire (3) slitting a pregnant woman ’s stomach with knives.

After providing the complete texts of the above-stated five reports for archival purposes, for comparison I also present the extremely sanitized versions of the same Mannar massacres, as recorded in two books by Sri Lankan historians (K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins) and a historian wannabe (Rajan Hoole).

(1) Tamils hit by scorched-earth blitz

[by Mary Anne Weaver. Sunday Times, London, Jan.27, 1985]

Long stretches of the narrow island of Mannar look like Vietnam did 15 years ago, after defoliation by American napalm. Many groves of palmyrah and coconut palm lie black and charred; others have been attacked with saws and cleared.

The Sri Lankan government claims that the palm forests are routinely cleared this way every year. But the civilians of Mannar say that the Sri Lankan army, engaged in a harsh and often arbitrary campaign of terror here in the north, is bent on transforming all of the island into a huge sand dune so that it can establish a defence frontline and deprive ‘the boys’ – the Tamil terrorists – of cover.

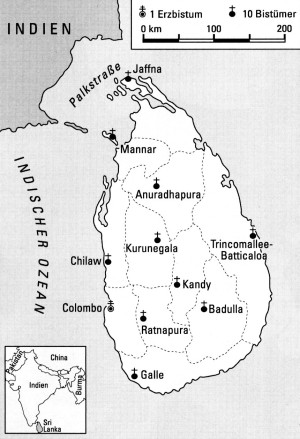

Mannar is 22 miles from India where six Tamil separatist groups have established training camps. Hope is in short supply on the island especially in the predominantly Tamil north, as the battle between ‘the boys’ and the ill-disciplined army slide into civil war. Civilians live in constant fear. More than 160 have been killed in Mannar district by rampaging security forces since December 4.

As the excesses of the largely Sinhalese army continue, the lines between the community which it represents – the 75% of the island’s population who are Buddhist Sinhalese – and the 20% who are Hindu or Christian Tamils, appear irrevocably drawn. Every village on the way to Mannar has burned-out homes and shops. A hospital lay in ruins. Nervous, arrogant soldiers dragged passengers from trucks and buses in their search for weapons.

The army in the Tamil north now numbers 3,600 men, but they are ill-trained and ill-equipped. ‘The authority of the army is confined to the frontiers of our camps’, Brigadier Salin Seneviratne, an ex-Sandhurst man who commands in Jaffna, told his superiors in a confidential memorandum last month.

The army in the Tamil north now numbers 3,600 men, but they are ill-trained and ill-equipped. ‘The authority of the army is confined to the frontiers of our camps’, Brigadier Salin Seneviratne, an ex-Sandhurst man who commands in Jaffna, told his superiors in a confidential memorandum last month.

‘We are despised here,’ one of the northern commanders told me. ‘We just cannot cope with the situation. Every week soldiers go amok. I’ve literally had to slap men from the ranks, and lock up large numbers to prevent them going on a rampage’.

The tiny market place of Mannar city is testament to the soldiers’ presence. Barricades, barbed-wire fences and burned-out oil drums litter the centre of the market, which soldiers razed to the ground in August after Tamil separatists ambushed an army convoy 30 miles away.

‘Everyone lives in dread here,’ said Hilary Joseph, a Roman Catholic priest. ‘No one sleeps at home at night. They are all in the jungle. Two priests have been killed by the army since the end of December. There is a regular priest hunt.’

We saw evidence of the massacre of December 4 all around us. It began early in the morning when three army jeeps hit a landmine. One soldier was killed and three were injured. Thirty soldiers then went on a six-hour rampage around Mannar. They attacked the central hospital, stopped vehicles and shot the occupants dead on the spot. They lined up 15 employees of a post office and killed eight. They opened fire on peasants in fields, attacked a convent and stripped nuns of watches, gold crucifixes and chains. At the end, nearly 150 people lay dead; 20 are still missing, mostly young male Tamils taken to army camps.

‘It took three days just to transport all the bodies,’ one social worker said. ‘There is no longer any petrol, no longer any movement. Life is dying here.’

At Talaimannar about 250 fishing boats were tied up by 11 in the morning, their working day ended. Two months ago, the Sri Lankan government imposed a naval ‘surveillance’ zone off the northern coast which limited fishing to close inshore. The result is a catch of minnows – and destitution for 1,200 fishing families.

Nobody has been permitted to leave the village since November, and we were the first visitors allowed in. ‘We are living in a state of siege,’ said one fisherman. ‘But it doesn’t matter. We will do whatever is necessary to continue to help the boys’.

(2) Gloves Off

[Economist magazine, Feb.9, 1985]

The Sri Lankan government seems to have abandoned its efforts to reach a settlement with the Tamils. It is not seeking to revive the long drawn-out negotiations with the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and the Sinhalese and Buddhist parties which collapsed in December, and as a result the moderate TULF has moved closer to the Tamil extremists who demand a separate state in northern Sri Lanka. The government now seems to be concentrating on a military victory. In a warlike gesture on February 1st it banned Sri Lankan newspapers from reporting military action against the Tamils.

However it is hard to see how the government can achieve any sort of settlement, military or political, unless it has the cooperation of India. The leader of the TULF, Mr Appapillai Amirthalingam, who says that the Sri Lankan government is turning all Tamils into militants, was in Madras at the beginning of February talking to the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOT), one of the groups fighting the Sri Lankan army. PLOT is negotiating with other militant groups – there are seven main ones – to try to set up a joint military command. India could help Sri Lanka by closing down bases in Tamil Nadu, where Tamil guerrillas train and where many Sri Lankan Tamils have sought sanctuary, but it is unwilling to alienate Indian Tamils.

Sri Lanka has around 11,000 troops, of whom 3,800 are deployed against some 5,000 Tamil guerrillas. Its soldiers are indifferently equipped and not used to fighting insurgents. A request for $100m of military aid from the United States was turned down when the American envoy Mr Vernon Walters visited Sri Lanka in December. America wants Sri Lanka to come to terms with the Tamils, even at the risk of upsetting the majority Sinhalese. The British have also refused to lend money to buy arms, though Sri Lanka is buying naval gunships from a British firm to help prevent guerrillas crossing from India.

The government is also trying some Israeli West Bankery, settling Sinhalese in Tamil areas in order to change the population balance. But this provocative action is likely to enourage more violence. In November, Tamils murdered around 80 Sinhalese who were living on land the Tamils believe belong to them.

(3) Letter from Sri Lanka: Finding a safe way in rough country

[by Michael Hamlyn. London Times, Feb.15, 1985]

The first checkpoint was seven miles outside Madawachchiya on the road to Mannar. A soldier waves us down. His officer – no badges of rank, but he spoke such good English that he had to be an officer – asked for our ID. A section of his men was arranged in attitudes of defence in the bushes and buildings around.

At the next checkpoint in the village of Murunkan, the officer asked me if I had any video cameras with me. I did not realize why until a few days later when it was reported that three British journalists had been arrested in Jaffna district for filming with such a camera. News such as that presumably travels fast.

It was true that the ministry had said there were no restrictions on my traveling in the north, but it proved to be difficult to find a car hire company and a driver prepared to risk taking me.

They were nervous about Tamil rebels who might kidnap me or blow up the car. They were also, more justifiably perhaps, afraid of the reaction of the Sinhalese troops engaged in putting down the Tamil separatist rebellion in the north. Murunkan, after all, is where two months ago more than 100 people had been brutally murdered by the security forces.

In the end, however, we were a reasonable combination. The Tamil extremists seemed unlikely to want to inconvenience the Western press, which has been giving them and their cause a good deal of valuable publicity, and the Sinhalese soldiery were prepared to be friendly with a Sinhalese driver even though he may have had some sympathy for the militants, having served a prison sentence himself for taking part in an earlier uprising in the south of the country.

At the Murunkan checkpoint the officer gave us a piece of advice. ‘Be careful’, he said. ‘They are all terrorists here, They are all thieves, they are all robbers. In any case, be sure to leave before six o’clock. There is a curfew then.’ The local inhabitants warmly reciprocated these sentiments, accusing the Army of being robbers and murderers. They accused those manning the Murunkan checkpoint of extorting bribes for allowing passage and helping themselves to items from luggage they searched.

There was also a fierce dislike of the attitudes shown by the Army and police towards the locals. ‘They make us go there, come here, and talk in the most offensive language,’ one local dignitary said. ‘They made one servant go and stand neck-deep in the middle of a pond for no reason; they were just amused to do it.’

The Roman Catholics – Mannar has a 60 percent Catholic population – were incensed a few days ago when the provincial head of an order of teaching monks, responsible for the whole of South Asia, a learned and distinguished man, and a Tamil, was, as they described it, ‘scolded with filth’ when he had to pass the checkpoint dressed in his long white cassock.

Priests are not popular among the soldiery as they have been loud and vociferous in their condemnations of Army barbarism. ‘I could take you off and kill you and burn your body,’ the security man was alleged to have screamed at the holy man. ‘And it wouldn’t be the first time.’

The locals believe it is all part of deliberate policy to terrify them into submission. In August last year, a gang of soldiers went berserk in the town after a rebel attack and burnt down a number of shops in the Grand bazaar.

The military commander, appalled by what was going on, according to local legend, prevented further soldiers from leaving camp by drawing his revolver and threatening to shoot, not them but himself. He has since been replaced by a man, the locals say, who has not made any expression of regret. When citizens complained about the massacre of villagers in a dawn raid, the only answer they got was that they must learn to cooperate with the armed forces and pass on any information about the extremists.

(4) ‘A Centuries-Old Struggle Keeps Sri Lanka on Edge’

[by Steven R. Weisman. New York Times, February 17, 1985]

Colombo: The grisly reports come in from the countryside almost daily. Army convoys are blown up by a bomb or land mine. Civilians are slaughtered in retaliation. In recent weeks, the violence on this beautiful tropical island nation off the southern tip of India seems to have reached new heights.

The Tamils, an aggrieved ethnic minority, are battling a government dominated by the Sinhalese majority and are increasingly demanding independence. In response, the Government has shopped around the world for arms and has pressed its military grip on the country. But the violence has increased. By official count, more than 500 soldiers and Tamil and Sinhalese civilians have been killed in the last two and a half months. An estimated 2,500 died last year.

For centuries, there have been hostilities between the Sinhalese and the Tamils. In recent years, violence erupted as Tamils protested moves by the Government to establish Sinhalese as the official language and make it harder for Tamils to obtain government jobs or get into schools. Now a cycle has become established in which each new massacre provokes another and pushes both sides into increasingly irreconcilable positions.

A turning point came in December when negotiations involving various factions collapsed abruptly. President Junius R.Jayewardene had offered the Tamils some autonomy in the northern and eastern parts of the island, but his proposal also called for the central government to retain police powers in those areas. After leaders of the moderate Tamil United Liberation Front rejected Mr.Jayewardene’s proposal, he withdrew it angrily and now is saying he will not negotiate with anyone who continues to advocate a separate Tamil state, a position that seems to rule out any new talks.

Analysts say that with the Sinhalese community so upset over the violence, Mr. Jayewardene, who is deemed a moderate by many, has less latitude than ever to achieve peace. The President and his United National Party came into power in 1977 with promises to help the Tamils, but since then he has felt it politically necessary to impose restrictions on them. Many analysts say now that it was a blunder for Tamil leaders to reject the Jayewardene proposal outright, giving the President an excuse for not dealing with them.

Placating his political foes is only one of Mr. Jayewardene’s problems. Another is curbing the excesses of his own army. So many hundreds of Tamil civilians have died in rampages by the police and army forces in recent months that even some in the Government question whether the President has lost control of the military.

The worst problems have occurred in the drier scrublands of the north peninsula, particularly the city of Jaffna, where the Tamils predominate. Last fall, spokesmen for guerrilla groups that have espoused a Marxist-Leninist line talked openly of driving the army out. Accordingly, the Government established a harsh ‘security zone’ through the peninsula in which all civilians need permission to drive cars or even use bicycles.

Charges against Army

In addition a ‘prohibited zone’ was placed among the entire northern coastline, barring entry by anyone. The head of the Jaffna Citizens Committee, R. Balasubramaniyam, said in an interview that the zones had deprived 40,000 fishing families of their livelihood. ‘We have had indiscriminate arrests, indiscriminate killing, unprovoked shootings, theft of jewelry and valuables by soldiers and the rape of women,’ Mr. Balasubramaniyam charged.

A senior Government official declared that Mr. Jayewardene was ‘anguished’ by what the official termed ‘the most undisciplined army in the world outside Africa’. The irony, he said, was that while preventing an immediate revolt by Tamils, the army’s excesses seemed to be sowing the seeds of revolt and resentment in the long run.

The Buddhist Sinhalese make up about three-quarters of the population, while the Tamils,who are Hindu, make up less than a fifth. But the army is about 95 percent Sinhalese, the result of packing by a Government increasingly concerned about loyalty in times of stress. Experts say that the problem with the army is less a question of its posing a political challenge to Mr. Jayewardene than of being unable to control fierce anti-Tamil feelings among the soldiers.

Help from India

Mr. Jayewardene, meanwhile, is trying to boost the army’s morale and strength. He brought in Israeli and British experts to train a separate police task force and has reportedly ordered helicopters, gunboats, small arms and armed personnel carriers from Britain, Belgium and China. Government officials deny reports that there were any arms requests of the United States. In any case, the official position of the Reagan administration is that Mr. Jayewardene must solve his problems politically, and be more willing to turn to one party that can help greatly – India.

There seems little question that the Tamils in Sri Lanka are deriving sympathy and sanctuary, and probably training and supplies, from the nearly 50 million Tamils who live in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi officially opposes an independent state for Tamils in Sri Lanka, partly because it would set a dangerous precedent for India’s dealings with its own independence-minded groups. But like his mother, the late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Mr. Gandhi is also reported to be reluctant to dissuade Indian Tamils from helping their fellow Tamils in Sri Lanka. Some Indian officials acknowledge that Mr. Gandhi could probably act to suppress some of the aid from Tamil Nadu, but they say he would be unlikely to move without some comparable gesture from Mr. Jayewardene. There is talk of a meeting between the two leaders, but nothing has been set.

(5) Exodus: Special Report

[by K.P.Sunil. Illustrated Weekly of India, March 24, 1985, pp.14-17]

Big Font Introduction

Every day, thousands of terrified Tamils flee Sri Lanka. Traumatised by the genocide unleashed by the army, and a cruel civil war that has scarred the emerald isle and taken the republic to the very brink, these people have abandoned their homes and homesteads, painfully built over the years. Their destination is across the Palk Straits. In India. Where they seek refuge and hope to rebuild their shattered lives. In the process, these refugees have created a situation not unlike the Bangladesh crisis. K.P. Sunil reports from Rameswaram on the boat people.

The Report Proper

[Notes: the dots in the text are as in the original.]

‘They are not human beings’, wailed an aging woman. ‘They are brutes…worse than animals…man-eaters…’ She was not airing a personal opinion. But voicing the sentiments of thousands of others, who, like her, have braved innumerable hazards during a perilous crossover from the island republic of Sri Lanka to the more hospitable shores of India. They are Tamils. Sri Lankan citizens who have lived for ages on that country’s soil. People with no roots here, now looking up to India for asylum on humanitarian grounds. Refugees from the violence and repression directed against them by the Sinhalese people and the Sri Lankan government through its security forces.

Rameswaram, a small coastal town in Tamil Nadu, is teeming with thousands who cross over in large numbers each day. In little fibre glass boats. In precarious country vessels. In large motorized launches. Entire villages of Tamils – old men and women, youth, children – are all coming to India, bearing marks of months of agony and suffering. The trauma, both physical and mental, is there for all to see in their drawn faces and hunted looks. For they are people who have witnessed their womenfolk being raped. People who have seen their kith and kin tortured and killed. People who have lost their all to the marauding Sinhalese mobs and military. Victims of an ethnic conflict that has converted Sri Lanka from a soothing Shangri La on the Indian Ocean to a maelstrom of violence.

|

| Security forces' actions in Mannar, 2006 |

Forty five year old Parvathy looks much older. She used to work as a maid in a rich Tamil’s house near Pesaalai in north-western Sri Lanka. She was deserted by her husband years ago, soon after their daughter Lakshmi was born. Lakshmi is now 16 years old. Last month as the two were working in the kitchen they were shocked to see the house suddenly filled with army men. (The men were away at work). The jawans pushed away the children, trampled on them with heavy regulation boots and set about gang-raping the women. Parvathy and Lakshmi, unnoticed in the kitchen, jumped out of the window and ran away. Parvathy, thereafter, became a nervous wreck. She was scared stiff to even venture close to her employer’s house and does not know what happened to them. Lakshmi and she starved for days without work. And when neighboring fishermen started talking of escaping to India, managed to join them and cross over in a little plastic boat – meant for 6 persons into which over twenty had got in. They had absolutely no belongings and looked up to India – its people and government – for help. ‘I will never go back even if things become quiet there. I would rather lead a poverty-stricken life in India. I am willing to work. If you people try to send me back to Sri Lanka I will run away.’

Sarojini, clutches an empty plastic bag to her bosom. It is the only possession she has in this world. Until recently she had been an agricultural worker in the village of Maanthai, barely 10 kilometers from Mannar. Only four kilometers away from Maanthai is army camp. The scene of several horrendous deeds. Sarojini was returning home from the fields one evening. With her was her 14 year-old nephew. As they stopped at a wayside shop for a drink, they heard the sound of approaching army jeeps. One of which screeched to a halt in front of the shop. An armyman in uniform jumped out and came towards them. He shouted at the boy to hold out his hands, palms facing upwards. There were calluses on the palms, the gain of toil on the fields. The armyman felt these. ‘So you are a little Tiger cub, are you?’ he thundered. The boy stuttered a denial. Reaching into the shop the man took out a soda water bottle. He broke it against a railing and using its sharp edges gouged out the screaming boy’s eyes. He swooned in a pool of blood. None of the passers-by dared to help – the other armymen stood waiting for exactly such a move, guns in their hands. Sarojini passed out. When she regained consciousness she learnt that the boy had bled to death. The boy had been her only relative.

There were rumors that some persons in the fishing village of Pesaalai some distance away were likely to make a break for safety. To India. Sarojini walked all the way to Pesaalai. And from there managed to get into a boat bound for India. She landed at Rameswaram, clutching a little plastic bag to her bosom – her only worldly possession. She shudders at the thought of going back. ‘Never,’ she shrieked. 'The place is a mad house. The people are raving lunatics. If you people don’t want us here in India, shoot us. Kill us. But please don’t send us back.’ But not all refugees wish to stick on here. There are others who are willing to go back when normalcy returns. When the atmosphere of fear is removed. People like forty year old launch-owner Yograj Nanattan of Pesaalai for instance.

Yograj is a reasonably well-to-do fisherman. He had been scared by the atmosphere of doom that hung over the entire Tamil area. And so he moved with his family to India. In his own motor launch. Carrying with him all his movable possessions including a color TV set. He had been unaffected by the riots until recently. But then the Sri Lankan authorities issued an order. No fishermen could go fishing more than 100 meters from the shore. Those violating the order were shot by the navy. This order virtually strangled the fishing community who had to live without a catch for days. All their meager savings had been used up and the only way out was to flee the country. Yogaraj started in his launch. In addition to his family members, there were about thirty others, mainly fishermen, who worked under him. ‘I shall go back when peace returns’, says Yograj. ‘I shall start my fishing operations once again. But all of us look up to India now. You have to ensure that peace returns to our land. Our boys, the Tigers, are valiantly fighting to make our land free. We want India to support them. That is all we ask from you.’ When asked about his opinion of India, Yograj was philosophical. ‘Well, the people here are good…very kind. The government is also doing its bit for us, though not much. They are only giving us some utensils, a mat and some other basic articles. You see, I am a reasonably well-to-do person there and am accustomed to much more. I am not asking for luxuries but your government could do a bit more for us.’ He is indifferent about India’s own impoverished economy. He waves aside the large body of Indians who exist below the poverty line. ‘We have suffered a lot. We have lost everything we possessed. You should help us.’

Fortunately, not all the refugees are dissatisfied with the treatment meted out to them. ‘We are refugees’, says Selvaraj – a shop owner from Talaimannar. ‘We have been virtually chased away from our own land and should be prepared to face anything here. The Indians have been very kind to us. We will not overstay our welcome. We have come here only because of the military excesses against us and are quite willing to go back as soon as northern Sri Lanka becomes peaceful.’

Selvaraj too had a tale of woe to narrate. He had been a shop owner in Talaimannar dealing in varied goods from provisions to cosmetics. He had under him a number of Tamil boys to mind the shop. He recalls that last December some army personnel came to his shop. They asked him and his boys to show them their identity cards, which, when shown, they promptly tore up. Then they started beating the boys with belts and laathis claiming they were Tigers. They hit Selvaraj accusing him of harboring dangerous terrorists in his shop. And finally departed taking one of the boys with them. It was later learnt that this boy had been taken to the Talaimannar military camp for terrorists, reputed to be one of the worst places of torture in the land.

Selvaraj, making use of several political connections, ultimately obtained an order from President Jayewardene himself permitting him to visit the boy. Brandishing the order, Selvaraj went to the dreaded camp. The authorities, on seeing the letter, asked him to first sign a document stating that he had met the person concerned. Then they asked him to leave. ‘I have got an order from the president saying that I can meet this boy. So you must let me see him,’ he demanded. ‘Yes’, laughed the officials. ‘And we have got it, in your own handwriting that you have already seen him. Now you may go.’ Realising the futility of the situation, Selvaraj went away. Two days later a military jeep stopped outside Selvaraj’s shop. The body of the boy was thrown out of it and the vehicle sped away. Selvaraj was struck dumb. He deserted his shop and with his family and employees went to Pesaalai. From there, he obtained seats in a launch at the rate of Rs.50 per head and fled to India. ‘I liked Sri Lanka’, he says. ‘My business was good. And I shall be happy to go back as soon as peace returns to the place. Until then, we are at your mercy.’

Eujeniu Kulas, a 27 year old youth was one of the most vociferous of the refugees at Mandapam. ‘Young men cannot walk the roads of Sri Lanka,’ he said. ‘They think that all young Tamils are Tigers and terrorists. The Tigers are gaining in strength and the Sinhalese are terrified of them. The army and police are unable to accomplish anything against the terrorists. That is why they are directing their wrath against us. We are innocent. But we are Tamils. Even children are not spared. Children, they say, are the Tigers of the future. In Mannar, some months ago they rounded up about 10 boys, and herded them in a truck to a nearby camp. They disappeared thereafter. According to information received from Tamils who have managed to escape from the camp the boys were bundled in gunny bags and set afire. Alive. Using petrol and old car tyres. This is how cruel they are. A pregnant woman was accosted on the streets by a police patrol. ‘You have a Tiger cub inside you. We will finish him,’ they shouted. They slit the woman’s stomach with knives. The woman screamed. She bled to death in front of several persons. But none dared to come to her help. We could not stand it any longer. We did the only thing we could do – cross over to India. We will go back. We will work hard and make our land the best in the world. We are capable of that. But first we should have a land which we can call our own. Our boys (the Tigers) are doing their best to make this dream come true. And we also look up to you Indians for help. Don’t believe a word of what they say over the Sri Lankan radio. Except the time mentioned at the beginning of a programme all the rest are blatant lies.’

A. Royton was an 18 year old student at the St. Xavier’s College in Mannar. He is today a refugee in the Mandapam camp, having given up his studies to flee to India. To be away from Sinhalese atrocities. ‘We are not safe even in the college chapel’, he says. ‘A Tamil father in the chapel of a neighboring college was killed by army men within the holy precincts itself. His crime was that there were several boys in his room. They were his students. But the army men claimed that they were terrorists. These boys were brutally tortured. And shot dead. They first slit the veins on their forearms with blades. They started bleeding and screaming in pain and fear. Then they were lined up against a wall and shot. They are inhuman, these army personnel. I ran away from my hostel. I walked for three days through the jungles, avoiding the main roads which are used only by army vehicles. I went to Talaimannar where my father is a revenue official in the government. He took me and my younger sister to Pesaalai from where boats were going to India. He stayed back with mother and sent us in one of them. We now look up to you to bring our parents safely across.’

Dharmakulasingham is a journalist. The Mannar district correspondent for two Sri Lankan Tamil newspapers – the Colombo-based Dhinapathi and the Jaffna-based Eelanadu. He has crossed over to India by boat from Pesaalai with his wife, Jeevabhavani, and his two daughters. As a journalist he had been in close touch with the Sri Lankan situation and was able to provide a comprehensive picture. ‘It all started with the Tigers’ attack on the Chavakachcheri police station near Jaffna in the third week of November last year. It completely destroyed the morale of the Sri Lankan armed forces. Ever since they have been trying to regain their confidence. By attacking innocent Tamils all over the place. They are too scared to take on the Tigers. All the so-called terrorists shot by the police and army are actually innocent Tamil youths. When the parents of those killed came forward to receive the body of their dead son, the authorities made them sign a paper stating that they were receiving the body of their son who was a terrorist – a Tiger. Most people were uneducated and used to sign the paper without even knowing the contents. Then flourishing this signed statement the officials periodically visit the houses of the victims saying that they suspect more terrorists to be hidden there. They harass and rape the women and torture the children. And shoot anyone who dares to protest.

‘You people will shudder at some of the atrocities and tortures perpetrated by those lunatics. They used to line up small school boys on the ground and trample them. And rejoice as the poor chaps scream and writhe in pain. Youths are herded into large gunny bags and sewn up. Then they pour petrol over the bundle and burn it along with its live contents. Women are beaten up mercilessly and gang-raped. After their lust has been satisfied they were shot like dogs. Many people, unable to tolerate the atrocities any longer fled to the jungles. Then the army helicopters come into operation. They spray acid over the forests. This begins to burn the skin and unable to stand it any longer the people come out of the forests only to be shot by waiting troops.

‘Most of us who have come to India have experienced little difficulty on the way. Nobody tried to intercept us. Maybe the navy wants us to leave Sri Lanka forever. Then they can loot our belongings and do whatever they want without even a token protest. Also, the fishermen transporting us are experts. They know the lay of the waters extremely well. They brought us along a route which had shallow waters throughout. No navy vessel would dare to come to those areas as they would run into navigational problems and also their vessels may get grounded.’

The internal problem of Sri Lanka has suddenly become an Indian dilemma. Every refugee is being fed for a few days at state expense. They are being supplied with two sarees, two dhotis, uniforms for children, basic utensils, a hurricane lantern, a mat and a blanket (totally valued at over Rs.650 per set). Fortnightly doles of Rs.55 for the head of each family and Rs.27.50 for each additional member (slightly less in the case of children), are also being made with which to subsist. Special ration cards are issued and under it they are provided with rice at 57 paise a kilo (market price around Rs 3.50 per kilo) and firewood at 40 paise a kilo (market price Rs.3.00 a kilo). And all this is certainly going to be a major drain on India’s tottering economy.

According to Naresh Gupta, the special officer in charge of the refugee camps in Rameswaram and Mandapam, the government is taking steps to avert some of the contingencies by issuing family identity cards (with photographs). ‘This would enable authorities to identify families at the time of repatriation’, he said. Another safeguard taken is to send batches of about 1,000 refugees to every district in Tamil Nadu to reduce the concentration of refugees in any one area. But these procedures are again fraught with difficulties. Several hundreds of families had already been dispatched to the various districts even before the issue of identity cards. How are they to be enumerated? What can be done to prevent unscrupulous elements from tagging on to the refugees to derive governmental benefits? What is the fate of children who are born after landing in India? (One woman, Monica Croos, had already delivered a baby boy at the Mandapam camp hospital on February 16. The number of pregnant women in the camp is so large that an entire block close to the hospital has been set aside for them.) Also charges of corruption and misappropriation of funds meant for relief work by the officials have been reported to the press by the refugees themselves. In the present uncontrollable situation, what can be done about such charges? These and other posers stare us in the eye and solutions are not easily forthcoming.

In the meantime, the Sri Lankan government has accused India of harboring terrorists (Liberation Tigers). Of providing them with refuge for conducting training camps. Of providing them with weapons and firearms to be directed against the government. All these charges have been repeatedly and emphatically refuted by the Indian government. And while all these accusations and counter-accusations are going on, more and more innocent lives are being lost. More and more persons are being displaced. India is being swamped with refugees. Persons with Sri Lankan citizenship and identity cards issued by the Sri Lankan government. On the other hand lakhs of stateless plantation workers who should have been repatriated to India long ago (under the Srimavo-Shastri Pact) still remain in Sri Lanka. With no hope of salvation in the near future.

Extremely Sanitized Versions of Mannar Massacres

How have the historians and historian wannabes of the blessed island masked and dodged the Mannar massacres by the Sri Lankan army, which precipitated the Anuradhapura massacre by the LTTE? Here are two examples.

In their hagiography of President J.R. Jayewardene who was holding the reins of government at the time, Professor K.M. de Silva and Dr. Howard Wriggins attempted to exonerate the Sri Lankan army by passing the blame onto the LTTE. Even Mannar was not mentioned. To quote,

“…the LTTE embarked on a vigorous campaign against the Sri Lankan forces and attacks on softer targets such as Sinhalese peasants in isolated settlements, as well as a ruthless programme of eliminating its Tamil rivals. They seldom directed their attacks against the security forces in open confrontations. When they did so, their attacks were generally easily repulsed. But one of the consequences of such confrontations was that quite often civilians were killed, either caught in a cross-fire or, on occasion, by soldiers on the rampage seeking to avenge the loss of their comrades in unforeseeable and lethal land-mine blasts. The LTTE, for its part, demonstrated its ability to strike deep into Sinhalese territory when, in May 1985, a raid into the town of Anuradhapura, the administrative centre of the North Central Province, left 150 civilians killed.” [J.R.Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: From 1956 to his Retirement, vol.2, Leo Cooper/Pen & Sword Books Ltd., London, 1994, p.618]

It seems that for these two academics, those Tamil-speaking Mannar peasants who suffered at the hands of Sri Lankan army were not “soft targets.”

Rajan Hoole, in his 2001 version of the Sinhala-Tamil conflict, deceptively condensed the Mannar massacres in merely two sentences. For one who has a predilection for painting the LTTE’s misadventures/failures and purported bickerings among ranking LTTEers in micro detail, it is doubtful that Hoole was totally naïve of the Sri Lankan army’s atrocities in Tamil land. To quote,

“The end of 1984 and early 1985 saw two major attacks by TELO, the Tamil group that was most closely cultivated by India. One was on Chavakacheri police station and the other on a troop train. There were throughout this period regular massacres by the Sri Lankan Forces. At Vattakandal in the Mannar District 40 civilians were killed at an army post and other civilians were forced to drink the blood of the dead.” [Sri Lanka – The Arrogance of Power: Myths, Decadence and Murder, 2001, p.214]

Given the evidence that the Mannar massacres perpetrated by the Sri Lankan army had been highlighted in the British and Indian print media by Mary Anne Weaver, Michael Hamlyn and K.P. Sunil so vividly, it is somewhat laughable to believe that Prof. K.M. de Silva and Rajan Hoole were oblivious to the Mannar massacres. One should infer that by downplaying the Sri Lankan army atrocities against Tamil civilians, Hoole was merely playing the role of partisan historian.

That the Sri Lankan army and police were being specially trained since 1982 in what is euphemistically termed as ‘counter-terrorism’ [but in reality annihilating, mutilating and murdering Tamil civilians] has been noted by de Silva and Wriggins in the succeeding paragraph to the one quoted above. They state,

“The Sri Lanka government began to divert an increasing proportion of its annual budget to the expansion and equipping of its armed forces. Total defence expenditure, as a percentage of total expenditure, rose from 3.0% in 1982 to 3.80%, 4.81% and 9.77% in 1983, 1984 and 1985 respectively. Along with this there was an escalation of military action against the Tamil separatist groups in the north and east of the island. The Sri Lankan armed forces were now better equipped and better trained than before. Much of the training was done in Pakistan, while small groups of Israeli and British mercenaries honed the skills of special counter-terrorist units in the army and police.” [p.619]

What has not been highlighted by historians K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins in this paragraph was whether the ‘skills of special counter-terrorist’ operations learnt by the Sri Lankan armed forces also included eye-gouging with the serrated edges of a broken bottle, killing civilians alive by bundling the victims in gunny bags and setting them afire, slitting a pregnant woman’s stomach with knives and bleeding young boys to death by slitting their arm veins with razors.

© 1996-2025 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.