Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Conceptualization of an IslandThe ultimate resistance to power-sharingby N Malathy

Studies The long, bloody and intransigent civil war in the island, its protagonists and its causes have been subjected to innumerable studies. These studies can be grouped into two broad categories. One category includes the studies of the many peace negotiations and the attempts to resolve the issues over a period of two decades and the other is the anthropological studies of Sinhalese, Tamils and the LTTE. The second category, that is the anthropological studies on all the three entities, has not received much attention. Whatever fascination each of these three sectors when put under the anthropological microscope may afford, some light has indeed been thrown on the perplexing issue of the Sinhala resistance to sharing power. Any international players who have attempted or are going to attempt to intervene to resolve the causes of this civil war must pay attention to this phenomenon and the cultural conceptualizations that are fueling this Sinhala resistance to power-sharing. Resistance to share power Simply put, why do the Sinhala people resist sharing power? A fairly standard response from an educated member of the Sinhalese will go something like this. The island belongs to all the people in this island and no part belongs to any particular group. Therefore, their argument goes, devolving power on a geographic basis is against the principals of equality. They will then add that past discriminations against Tamils were small steps taken to redress imbalances that were built up during the colonial times. They will also say that there is really no ethnic problem in the island but only a terrorist problem. How do the Sinhalese convince themselves of this line of argument in the face of massive electoral support shown by the general Tamil populace to the LTTE (terrorist) demands? This is the all-important understanding needed by any international players wishing to intervene to resolve the conflict. This understanding must take into account the existing view of the Sinhalese about themselves as the chosen people on a chosen land, the unearthing of “evidence” in the early to mid-20th century that strengthened this view and the early misleading conclusions contributed by western scholars with the limited information that was/is available. The monks’ legends T

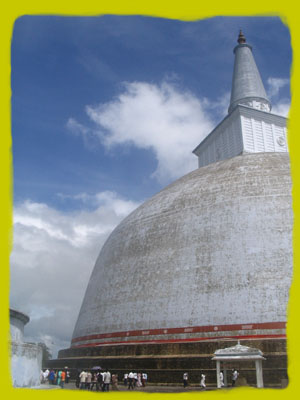

In pre-colonial eras, the monks’ stories that formed the basis of the Sinhala’s views of themselves depicted the Sinhalas as the people descended from a unique Lion (Sinha) dynasty from northern India when Vijaya and his friends arrived, civilized the island and established a great agro-civilization in it. The monks’ chronicles further add that Buddha himself came here after the Sinhala civilization was established and chose the people and the land to nurture Buddhism. There are many monks’ legends that reinforce this idea in different ways. Ones that have had a prominent place in contemporary times are, Vijaya, the original man himself, and Prince Dutegemunu, who defeated a Tamil king from the north. These legends knitted together to form a profound view of the Sinhalese as a people of the land who must face the challenges posed by “outsiders.” Metamorphosis of the legends into a rational view Part of the colonization process was to introduce western education and the accompanying precision of thought to the island people. This naturally challenged some of the monks’ stories about the origin of the Sinhalese and the visit by Buddha, etc. The origin thesis that was so deeply embedded into the culture has a staying power surpassing rational education; however, it needed to be wrapped with a veneer of rationality. Yet, the real challenge to this profound belief of a people about themselves came from the Tamils who asked for power sharing in the government. It is this rather than the need for precision of thought that ruffled Sinhalese feathers because the first needs to be dealt with only at an intangible level, while the second demanded the physical abolition of the core belief of a people. As the pressure from Tamils built up over the decades the defensive walls put up to protect the Sinhalese from abandoning their core beliefs were also reinforced, but in accordance with the rational thought that was now demanded in the international arena. The wherewithal of this latest defensive wall includes the defenses stated earlier about the island belongs to everyone, etc. Another refrain that came to be quoted regularly is the 2500 history of the island culture, referring to the landing of Vijaya, the “Adam” of the Sinhala people. This refrain, in particula,r is noteworthy because it harps back to the monks’ stories while hiding the irrationality embedded within it. Also worthy of note is the manner in which the Sinhalese subconsciously have started to refer to Sinhalese when they really mean the citizens of the island, the Ceylonese. This reference reveals much of the thought process of the Sinhalese that are indeed being hidden behind a veneer of egalitarianism. It is this all-subsuming Sinhala consciousness embedded in the monks’ stories and later presented wrapped in a rational scheme that forms the basis of the Sinhala intransigence towards devolving power. Depiction of the Tamil struggle as only a terrorist problem was an additional coat of paint given to the Sinhala veneer of rationality by the international community. Sharpening of the concept through parliamentary politics One can now insert the story of parliamentary politics into this scene to understand the failed attempts at resolving the issue, starting with the Dudley-Chelvanayagam Pact onwards. Indeed, the first two broken pacts that were signed and then abrogated were well-intentioned by the Sinhalese leaders, Dudley Senanayake and SWRD Bandaranayke, who both had a strong Ceylonese identity. With the insertion of two-party parliamentary politics and the sharpening of the Sinhalese identity, all subsequent failed efforts by Sinhala leaders to resolve the Tamil issue were half-hearted and were forced by India first, then later by the international community. Western blindness or Tamil-Sinhala friendship black spots A comment made by Terresita Schaffer, a former US ambassador to Sri Lanka and considered an expert in USA on Sri Lankan affairs, in a discussion in the American Public Eye radio immediately after the Norwegian-brokered peace process was on the cards is worth noting because it exemplifies the poor understanding of the cultural forces at play among the Sinhalese. She commented that there were many friendships between Tamils and Sinhalese, but there were many black spots in these friendships, referring to the avoidance of any serious discussion of the Tamil issue in these friendships. She was suggesting that these friendships must start to explore the serious issues. She, of course, had no idea about the impossibility of this project. As western nations attempt to intervene more and more deeply in this conflict they must make take on board this powerful and persistent concept in the minds of the Sinhalese of the undivided island that works at a very subtle level. This cultural mindset lurks behind the sophisticated arguments and thus remains very difficult to grasp. |

||

|

|||

he legends of the Sinhala people are different from other people’s legends in that it is a chronological history of State and Buddhism. When this was presented to western scholars they were impressed by its coherence and its exceptional subject that was different from the legends of other peoples which were mostly about gods. When archeology was initiated in the early to mid-19th century and spectacular ruins were uncovered, everyone was in agreement that the Sinhala Buddhist legends were indeed not without basis. This attitude of the western scholars reinforced the Sinhalese views about themselves. The discovery was emotionally more potent than it would have been otherwise, for it was a great cure to the wounded honor of a people subjected to white racism for centuries.

he legends of the Sinhala people are different from other people’s legends in that it is a chronological history of State and Buddhism. When this was presented to western scholars they were impressed by its coherence and its exceptional subject that was different from the legends of other peoples which were mostly about gods. When archeology was initiated in the early to mid-19th century and spectacular ruins were uncovered, everyone was in agreement that the Sinhala Buddhist legends were indeed not without basis. This attitude of the western scholars reinforced the Sinhalese views about themselves. The discovery was emotionally more potent than it would have been otherwise, for it was a great cure to the wounded honor of a people subjected to white racism for centuries.