Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

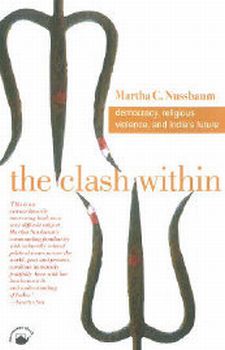

The Clash Withinby K. N. Pannikkar, The Hindu, Sept. 11, 2007

Bane of Fundamentalism The main purpose of this book “is to bring to the attention of people generally a complex and chilling case of religious violence (Gujarat 2002) that does not fit some common stereotypes about the sources of violence in today’s world.” Secondly, it also uses the case study of religious violence in India to challenge the “clash of civilisation” thesis advanced by Samuel P. Huntington. The author argues that the real clash is not a civilisational one between Islam and the West, but “a clash within virtually all modern nations — between people who are prepared to live with others who are different, on terms of equal respect, and those who seek the protection of homogeneity, achieved through the domination of a single religious and ethnic tradition.” IntoleranceInformed by these larger issues, Martha C. Nussbaum, a sympathetic commentator on the Indian political scene, to whom India is second home, combs through the fascist agenda of the Hindu Right and highlights the threat it posed to Indian democracy. The author recognises that under the onslaught of the Hindu communal forces Indian democracy almost “collapsed into religious terror”, but managed to survive due to the resilience of its political institutions. Although addressed to Europeans and Americans, Indians would do well to read this book, both for the information it contains and for its unambiguously secular and democratic stance. The sordid story of what the Hindu fundamentalist forces represented by the Rashtrya Swayam Sevak Sangh (RSS), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) did to the social, cultural and the intellectual foundations of Indian civilisation has now become well known. They claim to speak and act in the name of Hinduism, which they interpret in complete disregard of its known and celebrated plural and tolerant traditions. Their intolerance of those who hold a different interpretation of Hinduism has often led to physical intimidation and attack of even highly respected scholars and artists. DeparturesThe criticism of this tendency, the author rightly argues, is not to be interpreted as criticism of Hinduism, as the fundamentalist forces try to project. The criticism is of the departures from what Hinduism had traditionally stood for, which the author identifies as pluralism, toleration and peace. The implication of this opinion is that the Hindu Right does not represent Hinduism, however much they try to do so. “What happened in Gujarat was not violence done by Hinduism; it was violence done by people who have hijacked a noble tradition for their own political and cultural ends.” In that sense the perpetrators of violence in Gujarat are not only criminals but also enemies of Hinduism which they claim to serve. The Hindu fundamentalists had a holistic view of their agenda. It was not limited to intimidation and violence as happened in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Orissa and Madhya Pradesh. The violence in Gujarat and other states was an end product of the intellectual and cultural conditioning which preceded it for a fairly long period. In Gujarat, for instance, there was a general movement in education from “liberal and critical education to training and mechanical education” without any social science or humanities content. This is not a phenomenon confined to Gujarat alone, but is true of almost all other regions. Such a change in educational culture is a breeding ground for fundamentalist and Fascist ideas. At the all India level such an effort was manifested in the rewriting of textbooks which was part of a larger agenda of redefining the nation in religious terms. That the Hindu Right shores up its support through sustained cultural interventions is often overlooked. As a result the secular mobilisation has not been very sensitive to this dimension and therefore leaves the cultural space for communal manipulation. The Hindu communal forces are particularly active among the diaspora community. The “Hindu culture” is vented through community gatherings and student organisations in university campuses. This is primarily aimed at providing sensitivity to cultural tradition. Over a period of time the cultural consciousness of the diaspora community has been so much shaped on communal lines that they form a major support base of the movement, both politically and financially. It is well known that the International Development and Relief Fund has been channelling money to Hindu communal organisations like the RSS. It is reported that the main source of income of the VHP is the diaspora community. At any rate it is undeniable that they are a major player in the fundamentalist resurgence in India. ResilienceMartha Nussbaum’s account provides a grim reading. What she holds forth at the end, however, is optimism about the future of Indian democracy. In doing so she is influenced by the results of the election of 2004 which she characterises as the rejection of the politics of religious division, reflecting the resilience of Indian democracy. However, it would be premature to conclude that the communal threat has been overcome. For Hindu communalism is not a political phenomenon alone; it is as much cultural and ideological, as is so ably brought out by the author. |

||

|

|||

THE CLASH WITHIN — Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future: Martha C. Nussbaum; Permanent Black, D-28, Oxford Apartments, 11, I.P. Extension, Delhi-110092. Rs. 595.

THE CLASH WITHIN — Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future: Martha C. Nussbaum; Permanent Black, D-28, Oxford Apartments, 11, I.P. Extension, Delhi-110092. Rs. 595.