Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

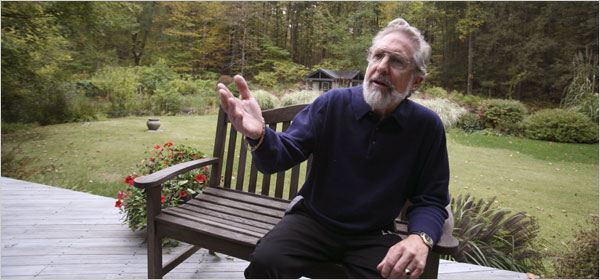

A Vision of a Nation No Longer in the USby Peter Applebome, The New York Times, October 18, 2007

COLD SPRING, NY: If any New Yorker were to become the theoretician for a new secessionist movement, it figured to be Kirkpatrick Sale. Mr. Sale, 70, was a campus rabble-rouser at Cornell in the 1950s long before Berkeley made being one fashionable, a model for a character in Richard Fariña’s classic ’60s novel, “Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me,” a writer who worked briefly with his college pal Thomas Pynchon on a musical called “Minstral Island.”

For half a century, he’s written more or less from the left on issues of decentralization, the environment and technology — in praise of Luddites, envisioning with dread the rise of the Sun Belt, lambasting Christopher Columbus as a despoiler of the American Eden and predicting environmental doom in a way that is making him at the moment look more prescient than cranky. And though he once described the personal computer as the devil’s work (its efficiencies producing more “social disintegration, economic polarization, and environmental devastation”), there he was Tuesday at his modern Adirondack-style house in the woods looking in delight at the inbox on his laptop. “Look at this,” he said. “There are 177 more messages from people who want to get on our mailing list. There’s nothing that has brought right and left together like this.” “This” was the Second North American Secessionist Convention, held Oct. 3 and 4 in Chattanooga, and attended by 15 delegates representing 25 states, plus 40 sympathetic observers. It followed, amazingly enough, the First North American Secessionist Convention, held the year before in Burlington, Vt. In this country, secession has not had the greatest odor since the 1860s, when it produced a movement now seen as racist, violent and a loser. But the spirit of Mr. Sale and his pro-secession Middlebury Institute actually has more to do with Vermont. There, a group called the Second Vermont Republic has become a small-bore local phenomenon, with its call for a “genteel revolution,” opposed to “the tyranny of Corporate America and the U.S. government,” and committed to “the peaceful return of Vermont to its status as an independent republic and more broadly the dissolution of the Union.” Hence those “U.S. Out of Vt!” T-shirts. Similarly, the language of the convention’s Chattanooga Declaration decries excess corporate and governmental power, says that the deepest issues of the time go beyond left and right and declares that liberty can survive only if political power is returned to local communities and states. “The American Empire is no longer a nation or a republic,” it says, “but has become a tyrant aggressive abroad and despotic at home.” Even those ill-disposed toward the idea of an independent Vermont, Hawaii or Alaska or to the new Confederacy envisioned by the League of the South might see some logic here. Back in 1981, the journalist Joel Garreau published “The Nine Nations of North America,” mapping out how economics, geography and culture really made it more logical for the United States, Canada and Mexico to be nine nations than three. Mr. Sale argues that the big theme of contemporary history, from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the evolution of the United Nations from 51 nations in 1945 to 192 now, is the breakup of great empires. And some on both left and right agree that the only cure for a federal government that’s too big and too powerful is to make it less big and less powerful. His relentlessly bleak vision is that catastrophic events, long term (collapsing dollar, out-of-control oil prices, climate change) and short term (Iraq, Katrina, government-sanctioned torture), will produce the downsizing of America, secession movement or no. “The virtue of small government is that the mistakes are small as well,” he said. Still, he concedes, there are a few roadblocks. Another 177 e-mail messages might feel like a revolution, but in that big, bad, computer-fueled world it’s just another tiny blip in the din. Local control might look fine in green, crunchy Vermont but perhaps looks less fine if it meant Southern states maintaining segregated schools and water fountains through the ’60s. Who is going to pay your Social Security, build interstate highways or finance NASA? And just how to make secession happen — legally and geographically — is, he concedes, still a work in progress. One option might be state by state, but then there are those Neo-Confederates in the South, or advocates of independent New England, Cascadia (Washington, Oregon, British Columbia) or New Acadia (Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and the four Atlantic provinces of Canada). Mr. Sale was asked what nation he’s prepared to live in. “I’d like the Hudson Valley,” he said. “I’d even include New York City, the whole Hudson watershed. It would be rich in resources and culturally unified. That’s the whole point of secession. If you want to leave a nation you think is corrupt, inefficient, militaristic, oppressive, repressive, but you don’t want to move to Canada or France, what do you do? Well, the way is through secession, where you could stay home and be where you want to be.” Of course, there might be problems here, too. What about the poor orphaned folks in distant Buffalo or Rochester or the vast empty acres upstate? What if the city didn’t want to join and wanted to be its own smug Cosmopolitania instead? Where would the Bronx, the one borough on the mainland, end up? Oh, well, life’s difficult. “You would call it Hudsonia,” he said, warming to the thought. “That’s the thing about secession. It fires up the imagination like nothing else.” E-mail: peappl@nytimes.com |

|||

|

||||