Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

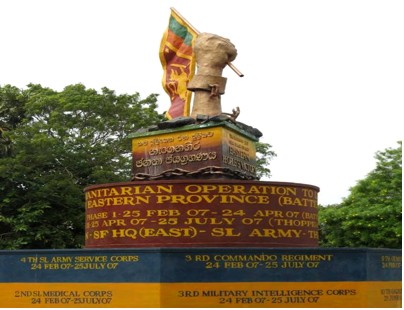

What Liberation?by Bhumi, Groundviews, Colombo, January 17, 2008

Based on field trip from 10th – 14th December 2007. Introduction This is primarily a collection of articulated concerns, observations and reflections of and about the ‘displaced’ and ‘resettled’. It is evident that there are several pertinent issues that need a rapid, effective response by protection and development actors advocating on behalf of these communities that are struggling to cope with simply living in the ‘liberated’ East. Several complaints and concerns were reported. The following are four dominant themes that seriously impact on the sustainability of resettlement in the Batticaloa district: 1. Lack of consultation and clarity The most precarious situation is that of the families displaced from Muttur area whose villages have been declared High Security Zones. Despite the unreasonable disproportionateness of the demarcated areas and dubious intents (where some accounts say that it is to be an economic development zone) what is most appalling is that the displaced villagers have not been told what their fate is going to be. They live in complete limbo. Similarly there have been several instances of military occupying public and private property without providing any alternatives or compensation in the ‘liberated; areas. This type of insensitivity on the part of the Government which cannot be explained by the ‘fight against terrorism’ leads to further alienation of the Tamil population. It was also noted that despite agreement and repeated reminders about the guiding principles for internally displaced people – the process of resettlement often fell far short of the minimum required standards. After the flagrantly forced resettlement of the Vaaharai area, the military and the STF did improve their conduct for the subsequent rounds of resettlement – but still fell short of the agreed upon standards. The hasty endorsement of some phases of the resettlement by UNHCR was also pointed out by some people as having set a bad precedent. One of the common sense suggestion by a displaced community members was – “if the return is voluntary, all they have to do is arrange for regular bus service. We long to go back to our homes. If we know public transport is available, we will go, see the place ourselves, if satisfied, come back prepare, pack and leave’. Whereas in almost all the phases of return the families never got a chance to assess the place – they were dumped there. The most egregious aspect was that the families returned to find that their houses had been vandalised and looted to the core. Since the LTTE fled without even taking their heavy equipment, the blame is squarely placed on the military that captured and remained in control of the area till the people returned. The list of items lost due to this looting runs into thousands of complaints in the newly established Vaaharai police station. Now that a majority of the people have been resettled, looking back, it leaves a bad taste about how the process was handled by the military and the civil authorities (who always are relegated to taking orders from the military). 2. Lack of Preparedness and Planning But the concern aired by many was, if the Government had resolved to pursue the military strategy, it must also have been prepared to take care of its citizens who were sure to be affected. There were no such plans or resources. The military agenda of the Government matched by the counter strategies of LTTE always creates displacement and misery for civilians. In almost all the cases in the East the Government was terribly under prepared and it was left to the UN and other NGOs to rush to fill in gaping holes in the response to IDP situation. If Government is clear on its military strategy of ‘defensive offence’, ‘retaliation’ or ‘pre-emptive strikes’ they must also have a clear strategy and preparedness to take care of its own citizens who are displaced as a direct result of their action. Time and again the Government failed and left it for the external agencies to fill significant gaps. Similarly even when it came to resettlement, the Government was woefully under provided moving back people without even the basic of needs in place. More on this later, but suffice to say that the people see, and justifiably so, the state more as ‘military liberators’ than as one caring for their needs and looking after their welfare. It appears that civil administration mechanisms (the GA and DS) are caught off guard most of the time regarding the timing of displacement and resettlement, making it difficult to prepare in advance. In the current context it is imperative that the resettlement/reconstruction plan is completely owned, lead and coordinated by the civil authorities headed by the Government Agent and the Divisional Secretary. In the current context the civil administration in the district – mostly Tamil – seem as marginalised and helpless as the communities they support. 3. Restriction of Access and Mobility Firstly, free access of goods, services and people is a sine qua non for sustainable resettlement –given the geographic and settlement characteristic of the Batticaloa district – with highly concentrated human settlements in the Eluvankarai area and vast cultivation land in the Paduvankarai area. To mark out people based on DS divisions and to have different registration process, different identity cards (in addition to the national ID) and to set in place security procedures to move from one DS division to the other is causing severe impediment to thousands of people whose daily living is dependent on crossing these boundaries. The lack of clarity as well as the constantly changing procedures brings in a great deal of uncertainty and misconception that limits mobility. In effect it traps them in ‘Bantustans’ with heavy military and paramilitary presence (and the inevitable harassment) is creating more misery. The security gains from such a hassle and harassment is not clear. The growing frustration though is very evident. A full six months after ‘liberation’ and capture, now to demarcate areas and to consider formerly LTTE-held territories as restricted or no-go areas defies logic. It did make some sense to stringently regulate movement across borders when some areas were controlled by the tigers. But, not any more. To restrict access into these areas for humanitarian agencies, Sri Lankan civil society and for even ordinary citizens of the district now is beyond reason. Given that the whole area is now under the control of the military, to claim that access is denied to ‘prevent infiltration’ sounds strange. Infiltration from where? Isn’t the rest of the district under the military control any way? The other reason given is to ‘prevent assistance getting into the wrong hands’. Aren’t these places cleared of ‘wrong hands’ and even if any one still remains having survived the long period of blockade, he sure must have figured out or is being sustained by other supply routes. The point is that the demarcations and restrictions do not seem to have a compelling security logic which could not be managed by the other military architecture like check points and cordon and search operations. What it ends up doing is frustrating the resettlement and humanitarian work and delaying the integration with the rest of the district and country. Even more baffling is when humanitarian agencies had been denied access ‘for protection reasons’ to very places where the ordinary people were resettled – some of them forcibly. The delays in access contributed to the lagged response to the resettled and more often than not the agencies were presented with crisis situation – lack of shelter, lack of water, lack of food etc- which could have been easily avoided with easy access and adequate time for suitability and needs assessment. Bureaucracy and red tape are commonplace and many agencies continue to face problems of access. Clearance procedures, when they are clear, are said to take anywhere within 48 hours to a week and only agencies working on ‘development’ are allowed access to West Batticaloa – as a result, addressing protection issues of IDPs and the resettled has become a serious concern. Access to humanitarian assistance in areas like Vellaveli, Paddippalai and Vavunatheevu was severely delayed and agencies are still subjected to cumbersome procedures in order to obtain permission for access. Having permission is no guarantee for access which also depends on the grace of the personnel manning the crossing points. 4. Protection Concerns of the Displaced and Resettled Communities This is obviously evident in Batticaloa. On the day of the ‘public’ meeting held by the TMVP (10th of December 2007) groups of civilians – including the displaced – were rounded up by armed cadres and forced to attend the meeting (which was a joint exercise by both Pillayan’s faction and Karuna’s commanders). At approximately 8:20 a.m. around ten/twelve armed cadres were seen herding people into CTB buses in Alankulam on the Colombo-Batticaloa Road within sight of the police and army who stood by. This was repeated during the course of the day throughout Batticaloa – people were taken from Kovils, resettled villages and even bus stations. 12 bus-loads of people – including the recently resettled were taken from Vaharai and 7 buses taken from the Badulla Road area (Batticaloa West). A meeting was held the day before in Pankudaveli (Batticaloa West) where the TMVP ordered that one member from each family must attend the public meeting. There are frequent reports of abduction and extortion by TMVP cadres. The construction industry in the district is one of the prime extortionary target and even the Government schemes like the world-bank funded housing program seems not to have been spared. Normalcy and durable and sustainable resettlement cannot happen as long as the Government turns a blind eye to the climate of fear, insecurity and terror created by the different TMVP factions of what was the Karuna Group. They carry arms in public, have offices where they summon, inquire and detain civilians as they wish. They have forcibly taken over private property and set up offices across the district and have even begun setting up more fortified establishments by the main road as in Maavadivaembu. They engage in joint cordon and search operations with the security forces (though this is more prevalent in the Ampara district than in the Batticaloa district) all in broad daylight and in complete cooperation of the Government forces. Given the overwhelming physical evidence in the district, bland denials may not absolve the Government of complicity. The Government must be held accountable for the violations of the TMVP/Karuna/Pillayan group who are roaming freely with arms and are engaged in serious violations including abductions, intimidation and extortion. The situation is worsened by the increasing tension between the Muslims and the Tamils within the District (in Arayampathi, Eravur and Valaichenai in particular). Rumours that Pillayan is supporting Muslim armed groups in order to win favour is rife and the security situation is deteriorating with the recent abductions of Muslims – including recently that of businessman Hassanar-Hayathu Mohamed from Eravur. The general sentiment is that the tension amongst the two communities will worsen before it gets better, particularly given the impending elections. It is widely felt that in this dimension the situation is much worse in Amparai than in Batticaloa. The impending elections will only help bring these destructive trends to the forefront as ‘democratic politics’ in the ‘liberated’ land. Before the split within the TMVP, families faced a clearly defined enemy, though with a loose command and control structure. Now, with many commanders vying for control, families face the dilemma of whom to suspect or even to turn to. Before the split, the TMVP acted as a sort of ‘buffer’ between the LTTE and the Sri Lankan military. Now, even the agencies are unsure of whom to contact and communicate with when faced with complaints of abductions and harassment. This also means that because of the presence of various factions and increasing confusion, responsibility can be easily shifted. So it is of little surprise that despite the publicised resettlement plans of the government, the culture of impunity and sense of lawlessness is widespread throughout the district. The security situation some people opined is worse for the communities now than before when you had predictable sources of threat with predictable reactions in predictable geography. Space for public gathering and advocacy is severely limited and fear, mistrust and insecurity is widespread and worsening rapidly. ‘Protection’ is an essential component of any resettlement intervention – most of the community members rank this as one of their top concerns. There is reluctance on the part of the government to accept a role for agencies in this sector in the same way as in shelter, water and sanitation and livelihood. Hence it has been very difficult to include this as a separate section in the resettlement plans. Agencies, primarily with protection mandate have not been provided access. It was an uphill struggle, agencies reported, to get protection elements incorporated into the Government’s resettlement plans – ‘it was taken to the CCHA but don’t know what happened thereafter’. Given the extent of violations reported from the resettled area it is absolutely essential to ensure that ‘Protection’ gets headline attention as a separate sector in its own right. The CCHA was necessitated because every issue in the areas had a security angle and a mechanism to include key decision makers from the security establishment was considered a good idea. But it appears as if the accommodation has gone to the extent to render the mechanism ineffective for immediate problem solving for operational purposes. The CCHA’s credibility as a useful body for solving protection concern is under threat. The following in brief are some of the ‘Protection’ concerns that were repeatedly mentioned in the district. • Abductions and forced recruitment There have also been a number of complaints of forced recruitment and re-recruitment committed by the various commanders within the district. However, it must also be noted that most incidences of abductions and disappearances go unreported – there is a real fear of retribution if families complain to agencies. In the absence of any action taken by the military or the police who stands by as this continuous to occur, there is hardly any one to whom the people could go to. • Harassment and intimidation • Harassment and intimidation of humanitarian workers • Looting • Militarization of Return Areas In Batticaloa West, after each return, there is an intense period of searches and round-ups – and in some incidences, the military have been accompanied by the TMVP. Once the entire return ‘process’ has finished, the newly resettled are often subjected to nightly checks by the military. Suspicions of LTTE connections is widespread (in Karadiyanaru and Pankudaveli for example) and the ‘culprits’ are arrested. Once released after interrogation, many are unwilling to go back to the village fearing further harassment. There is a gradual tick of ‘incidents’ allegedly by LTTE infiltrators in the area which threatens to take the situation in a downward spiral. There have also been incidences of military harassment. For example, in Karadiyanaru, on the 11th of December, a father was beaten up when defending his daughter who was questioned about her and her husband’s previous ties with the LTTE. In Vavunatheevu and Paddippalai, there have been complaints of harassment of women returnees by the military. A number of women are left alone in their shelters as men go elsewhere to look for work. Visitors staying overnight in both West Batticaloa and Vaharai are told to register themselves with the Police – or else face ‘severe consequences’. This includes construction workers and masons. An ordinary casual labourer looking to eke out a living through daily labour has to get a recommendation from the Grama Sevaka of his village endorsed by the Divisional Secretary of his division and can work only in projects of agencies that have been approved by the Government Agent and cleared by the Divisional Secretary. In case of house construction the beneficiary family has to take the mason to the police and register him with them attesting to the fact that he is working on their house. For an agency building houses through 8-10 teams of masons with about 40 workers this can mean a logistical night mare. Frequent delays of construction work and permanent housing is now commonplace due to the tedious paperwork. • Mine Clearance Since March, over a 100 UXOs have been found by communities – including in resettled areas. Villages in Kopaveli and Marapalaam have discovered UXOs and claymores – both newly resettled areas. There is a general atmosphere of confusion as agencies are given mixed information as to which areas are cleared and which are contaminated. According to the Batticaloa DS some areas have not been cleared and so, access is restricted – yet according to FSD and MAG, these areas have been de-mined. Delays in clearing areas and delays in procedures to obtain landmine clearance certificates have now become a regular excuse for restricting movement and access to both civilians and humanitarian actors. While the real threat exists in some areas, in some areas people believe it is being used as an excuse to restrict mobility. Either way it is incumbent on the Government to clarify. • Echilampatthu Resettlement concerns in Vaharai and Batticaloa West Other than the protection concerns raised above, several other issues plague the resettlement process. In brief –

In Vaharai, long-term livelihood stability is a pressing concern. Communities rely heavily on the surrounding jungle areas for their economic survival. But this proves difficult – people are scared to move about alone and most jungle areas have restricted access. Farmers who have received seed paddy by agencies have either received it too late (and have missed the cultivating season) or are denied access to their paddy fields and now rely on subsistence farming as a means of survival. The military has now banned all women under 20 from prawn farming. In one village, women have been asked to bring Rs. 100, a princely sum for many in the area, for a photo ID for prawn fishing – or else they will be denied fishing permits. Furthermore, areas previously known for good catches of fish now fall as ‘restricted areas’. In Arthuvaai at least a hundred to 150 families are completely dependent on fishing for their livelihoods but due to a navy checkpoint access is restricted. Even when permits are granted – the arbitrary way it is administered and the infeasible timing – makes it a struggle for the fishermen. The general uncertainty of a fisherman’s livelihood is further compounded by such measures. The recent spate of resettlements in Batticaloa West took place on the 20th of November – just short of the paddy cultivating season. This also means that even small-scale cultivation or subsistence farming is impossible and this is made worse by the rains. As a result, income generating activities is at the standstill. Families that stored paddy before their displacement have returned to find it looted and cattle and livestock have all gone missing. Those who worked as labourers in paddy fields cannot return due to restricted access. The widespread shortage of rice in the district is taking its toll on the newly resettled – food is scarce and the general sentiment is that the situation is going to get much worse. Of the 375 families resettled in Kittul, at least half rely on fishing as a means of survival. Local shop owners have supplied them with nets on condition that they sell their fish to them at a fixed price making it even harder for the families to make ends meet. Fixing the price of fish and even implementing a tax on fish is a frequent occurrence in Batticaloa West. There have also been repeated reports of the STF ‘borrowing’ the families’ motorbike or bicycle. Given the wide expanse of area and the need for people to now travel great distances to work/find work, this is severely delaying and hampering any means of income generation. The sentiment among agencies is that livelihood assistance will have to continue for at least another 8 months or so – a daunting task given the increasing donor reluctance to fund conflict-prone areas. But it is clear that the security situation is not conducive for livelihood sustainability which means that the resettled have no choice but to wait. Livelihood restoration in the district is more than mere infusion of capital and resources – it requires stability, mobility and certainty.

In Batticaloa West, the people were resettled before making any assessment or preparation for shelter. Most of their original shelters had been damaged, vandalised and looted. As a result when people were sent back a majority of them had to move into tents and temporary shelters. Their original houses of clay and Cajan have either fallen into disrepair due to the rains, or have been looted. The frequent rains have caused delays in construction work on transitional and permanent shelters. UN and international agencies, who were not allowed to go in until recently, now are scampering to cover the communities’ immediate shelter needs (Cajan roofing, pipes, tents and ropes) on Government’s last minute request. But long housing needs and household necessities (like saucepans and other utensils) are still in dire need. The government has recently started to distribute Cajan roofing (as distribution was on the 12th of December) which is a positive sign. In Vaaharai, where again people went back to looted and damaged houses (the damage due to shelling and artillery attack was heavy here) the situation has improved with the different agencies stepping into provide transitional shelters. The quality is mixed. While some meet the minimum standards, others are too fragile.

In some parts of the district under the government’s housing scheme, the North-East Housing Reconstruction Program (NEHRP), one scheme permits the newly resettled to receive grants in three instalments. The first two instalments of Rs. 50,000 and 60,000 have been paid and construction work has been completed up to a certain level. However, despite repeated requests for the third instalment, families have not yet received it. Complaints have been made to both the DS and the police but nothing has been done about it. Under another scheme of the same program, the government has pledged to supply the building materials and bear the cost of labour. According to community members, the timber (coconut) and the tiles given are of very pure quality. The DS has promised to follow up on this but to date, no action has been taken.

In Vatavandi, a scheme of houses was handed over by the government to beneficiaries in a much-publicised ceremony. What has not been publicised however was that many of these houses are incomplete. Some houses have incomplete roofing, flooring and some even lack toilets, doors and windows. Again, complaints have been made repeatedly only to be met with excuses by the relevant government agents. Sustainable returns and livelihood stability remains only a hope in Batticaloa West. People are far from settling into stability. In areas of Cenkaladi and Marapalaam returnees still live in schools and community buildings which have been damaged due to the conflict.

The food situation in Vaharai is worsening. Families have been living on rations for over a year now and although these rations fulfil their calorie requirements, they by no way fulfil their nutritional requirements. . The Government initially is supposed to have promised 6 months of rations. But soon after resettlement in April 2007, the people only received rations for two weeks. After prolonged gaps, some agencies stepped into fill the breach. The rice shortages have resulted in increased prices. The inability of fishermen to seek out their living has also resulted in exorbitant prices of fish. A coconut is Rs. 35 (as of December 2008); a kilo of rice is Rs. 80. Due to access restrictions, the rain and late cultivation, families struggle to make a living and the Rs 600 (which ends in January) a month given by SLRC is clearly not enough to survive with dignity. According to the WFP-Government rationing system, resettled communities must be given 6 months worth of rations. However, given the shortage of rice in this country, the returnees in West Batticaloa have been given been compensated with wheat flour instead. The distribution mechanism is very erratic and leaves large gaps. 70% of the resettled villages are not receiving complimentary food and only 30% are receiving complimentary food. The timing of the return has meant that the communities have not been able to fully capitalise on the cultivation season. Thousands of families have missed out on the season and hence the region as a whole is entering into a situation of food scarcity. Despite the much-publicised claims of liberating the East, stability in Batticaloa is a long-way away. As armed political parties fight for control, civilians are once again caught up in the ensuing political turmoil. The displaced and resettled suffer in the name of ‘security’ and it will be a long while before they begin to lead their lives with some degree of normalcy. The culture of impunity has widened and the sense of lawlessness palpable as violence, disappearances, round-ups and armed cadres are a way of life in the District. The issues discussed in this paper need to be advocated on – at international, national and district levels.

| ||||||||

This is not a general analysis of the political and security situation in Batticaloa. The military and STF are consolidating their recent gains, the LTTE is intent on destabilizing, the security forces are retaliating, the multiple splits in the Karuna faction and their overall ‘control and influence’ of communities by coercion, their simmering confrontations with the Muslim community and the impending local government elections - all make up for interesting times ahead. What happens in the next few months could have serious ramifications for the future peace process. The situation urgently calls for a thorough social, political and security analysis. But that is not the purpose of this note or the visits. Neither is it a compilation of the severe hardships and harrowing stories.

This is not a general analysis of the political and security situation in Batticaloa. The military and STF are consolidating their recent gains, the LTTE is intent on destabilizing, the security forces are retaliating, the multiple splits in the Karuna faction and their overall ‘control and influence’ of communities by coercion, their simmering confrontations with the Muslim community and the impending local government elections - all make up for interesting times ahead. What happens in the next few months could have serious ramifications for the future peace process. The situation urgently calls for a thorough social, political and security analysis. But that is not the purpose of this note or the visits. Neither is it a compilation of the severe hardships and harrowing stories.