Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Starting a PartyAnd hoping to crash Singapore's Parliament againby Seth Mydans, The New York Times, May 18, 2008

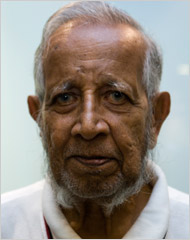

IT might seem late for a fresh start, but that is the story of J. B. Jeyaretnam’s life, a political intruder who refuses to stay away. “We are just beginning!” he exclaimed at a small news conference announcing the formation of a new party, the Reform Party. It was an unusual phrase to hear from an 82-year-old man who has been running for office — when the courts would allow him — since 1971. But Mr. Jeyaretnam seems unable to stop pushing, a man at the mercy of his own force of personality, certain of his principles, uninhibited and seemingly immune to intimidation. He paid his way out of bankruptcy a year ago, after having been convicted in 2001 of defaming members of the ruling party; ordered to pay damages; barred from the practice of law; and expelled for the second time from Parliament. He says he has lost count of the number of times he has been sued for defamation for his political statements. “We in Singapore are denied the rights to speak up, to tell the government to change course,” he said at the news conference. He widened his eyes and smiled a puckish smile, displaying three large, widely spaced teeth, and rededicated himself to the rescue of his nation. “The most important thing,” he said, “is that what we have to bring about — and I’m saying it quite seriously — is the liberation of our people, the empowerment of our people.” It seemed an outsize vision for this lone crusader at this late stage. He said 10 people had enrolled in his party; others had declined to step out into the cold light of open opposition. But it is not so much his mission or his party that drew reporters, but the phenomenon of Mr. Jeyaretnam himself. His persistence and his defeats are woven through Singapore’s history as a sort of counterpoint to its steady rise to affluence and economic success. In its 42 years, this city-state of 4.5 million people has built what its founder, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, in a recent interview called “a first world oasis in a third world region.” Most people accept restrictions on civil liberties and free speech as the price of their material well-being. Few people, even the discontents, call for fundamental change as Mr. Jeyaretnam does. “We are quite narrow minded,” a 16-year-old high school student said, asking that her name not be used when talking about Mr. Jeyaretnam. “We think about getting a degree, getting a good job, that’s all. There aren’t any political discussions. It’s not really our culture. We just study and that’s it.” WHATEVER his support, and whether or not he held a seat, Mr. Jeyaretnam has represented the idea of an opposition in a system that offers little role for one. For Singapore’s first 16 years as an independent nation, since 1965, Parliament did just fine as a monopoly of the People’s Action Party of Mr. Lee. In 1981, after what he says were half a dozen attempts to win a seat, Mr. Jeyaretnam crashed Parliament’s gate in a special election as its first, and noisiest, opposition member. His wife, Margaret, whom he had met when they were law students in Britain, died of breast cancer a year before the election, and it is one of Mr. Jeyaretnam’s regrets that she did not live to see him win. Mr. Jeyaretnam’s relationship with the legislature since then has been defined by the establishment’s moves to eject him and his own attempts to get back in. He lost his first parliamentary seat in 1986 after being fined and jailed for a month, when he was convicted of making a false declaration of his party’s accounts, a charge he says was politically motivated. Of the five general elections since then he has been legally permitted to run in only one, in 1997. Though he did not win, he earned a special nonconstituency seat as “top loser” under election laws. He held that seat until his latest conviction for defamation in a suit whose plaintiffs included Goh Chok Tong, who was prime minister at the time. The next election is due by 2011 and Mr. Jeyaretnam plans to run again “if I’m still here.” He added, in his commanding voice, “I’m 82 and still fit.” The People’s Action Party is a brilliantly successful political meritocracy that has all but monopolized the political talent here. And that, says Mr. Lee, is the only way it can be. “We do not have the numbers to ensure that we’ll always have an A Team and an alternative A Team,” he said once, when asked why Singapore did not have a vigorous opposition. “I’ve tried it. It’s just not possible.” Since Mr. Jeyaretnam opened the door, there have never been more than four opposition members of Parliament. Today, only two of the chamber’s 84 members represent opposition parties, and unlike Mr. Jeyaretnam, they take a decorous and cooperative approach. Mr. Jeyaretnam’s flamboyance has clearly irritated Mr. Lee over the years, and the government-friendly newspaper Today recently called their relationship one of the world’s longest-running political feuds. “His weakness was his sloppiness,” Mr. Lee wrote in his autobiography, “From Third World to First.” “He rambled on and on, his speeches apparently unprepared. When challenged on the detailed facts, he crumbled. “Jeyaretnam,” he writes, “is a poseur, always seeking publicity, good or bad.” HE does indeed love the limelight, but it is far more than a pose. Like with some dissidents in other nations, Mr. Jeyaretnam’s single-minded pursuit of a moral vision seems to be a compulsion. “Funnily enough, I enjoy the fight,” he said in an interview. “It’s true. And if I had to give it up I wouldn’t know what to do.” A practicing Anglican Christian of Sri Lankan descent, Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam was born in 1926, was raised partly in what is now Malaysia and received his law degree from University College in London in 1951. His son Philip has followed him into law and is president of the Law Society of Singapore. His other son, Kenneth, is an economist in London. Mr. Jeyaretnam says they were among the benefactors who helped pay his way out of bankruptcy. Back in Singapore with his British law degree, Mr. Jeyaretnam rose quickly in the legal establishment, serving as a magistrate, district judge, prosecuting counsel, registrar of the Supreme Court and chief of the Subordinate Judiciary, a position of status and influence. He resigned in 1963 at the age of 37 and went into private practice because, he said, “I was disillusioned, completely.” In 1971, he made the first of his many unsuccessful runs for Parliament. At the news conference he was asked the question that lies at the heart of people’s fascination with him: why he continues after all these years of what seems like futility. “I am concerned with reform and with people’s thinking about the real values in life,” he said. “Why are we here? What is the purpose of our being?” |

||

|

|||

Last month he was back after six years of political banishment, the grand old man of political opposition ready to joust again with Singapore’s immovable political establishment.

Last month he was back after six years of political banishment, the grand old man of political opposition ready to joust again with Singapore’s immovable political establishment.