Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Bold Colombia Rescue Built on Rebel Group's Disarrayby Simon Rivera and Damien Cave, The New York Times, July 4, 2008

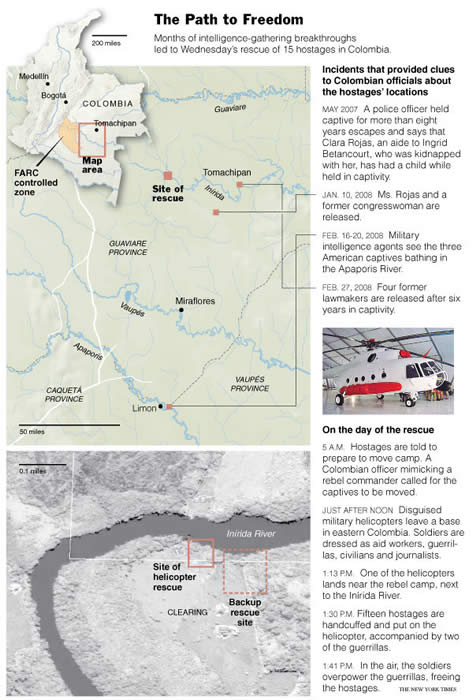

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — At 5 a.m. on Wednesday, the sun had yet to peek through the jungle canopy in this country’s Guaviare Department when the guerrillas told their captives to gather their belongings. A call had come in from a top adviser to Alfonso Cano, their new supreme commander. He said to move. Immediately. Or so the guerrillas thought. In fact, the gravelly voice that sounded so full of authority belonged not to a grizzled leader of Latin America’s most feared insurgent group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, but rather to a government officer. The fighters had been duped. With the help of satellite telephone intercepts and a spy who infiltrated the FARC’s upper echelons, the Colombian military had managed to plan and execute an operation that ended a long-running international hostage saga and upended Colombia’s four-decade civil war. The voice was simply the most dramatic touch in a daring rescue that exploited the recent disarray within the FARC. The insurgency has now lost many of its top leaders and its most prized hostage: Inrgrid Beancourt, the French-Colombian politician whose captivity since 2002 has attracted attention worldwide. Its founder, Manuel Marulanda, has died; security forces killed its second-in-command, Raúl Reyes, in March; and some 3,000 combatants have deserted in the last year. The rescue, described by commanders of the Colombian Army and officials in Washington and Bogotá, was almost exclusively a Colombian operation that highlighted the growth of a military that has benefited from $5.4 billion in aid from the United States since 2000. And while many here and in Washington stressed that the FARC remained a powerful force of several thousand fighters, earning around $200 million a year from drug trafficking, some analysts suggested that the raid combined with continued pressure might push the rebels to negotiate for peace. “It’s reaching the point where most of the leaders of the FARC are going to say, ‘We’re not going to win, we don’t have a chance,’ ” said Peter DeShazo, director of the Americas Program at the Center for Stategic and International Studies in Washington. “And when they reach that point, then political negotiation becomes more possible.” The rescue alone could reverberate across the region. Hugo Chávez, the leftist leader of Venezuela who negotiated previous releases of hostages held by the FARC but failed to free Ms. Betancourt or three American contractors also rescued Wednesday, has lost the regional spotlight to Colombia’s president, Álvaro Uribe, his top rival and a staunch ally of the Bush administration. At least temporarily, Mr. Uribe, one of Latin America’s most market-friendly leaders, has usurped the regional agenda. The White House’s broader goal of stabilization for the Andes may still be a long way off. Coca cultivation surged by almost 30 percent last year in Colombia, which still provides 90 percent of the cocaine found in the United States. Meanwhile, drug enforcement officials here and in Miami say that traffickers have developed ingenious new ways to move their product, including semisubmersible crafts. But for the FARC, the game has changed. The gritty leftist insurgency, which has survived for decades in the jungles of this Andean country and provided military cover to the world’s most productive coca growers, fell prey to an elaborate ruse that Colombia’s defense minister, Juan Manuel Santos, likened to a Hollywood script. Ms. Betancourt, who was reunited Thursday with her family, also said the raid seemed almost too fantastic to be true. It became real only when she saw Cesar, her captor, become a captive. “Suddenly, I saw the commander who, during four years, had been at the head of our team, who so many times was so cruel and humiliated me,” she said. “And I saw him on the floor, naked with bound eyes.” FARC’s Long History No other rebel movement is as well known in South America as the FARC, nor as widely reviled. Founded in 1964, after more than a decade of political violence that became the basis of the country’s armed struggle, the group’s power accelerated during the 1980s and early ’90s when the guerrillas allied with Colombia’s drug cartels. While smaller Marxist groups sprung up throughout the region, the FARC’s combination of ideology and money earned from protecting peasants growing coca gave them a force of as many as 17,000 fighters a decade ago and the ability to strike at will. Drug money fueled the violence. It poisoned the government with corruption as right-wing paramilitaries and the FARC killed, kidnapped and competed for control of cocaine trafficking and the country. “The FARC and the paramilitaries in the mid-90s both had shots in the arm from the drug business,” said Bruce M. Bagley, chairman of the International Studies Department at the University of Miami. “They put the Colombian government on its heels.” A turning point came in 2000 when Congress and President Bill Clinton agreed to send Colombia more than $1 billion to emergency aid to battle drug traffickers and their allies. President Andres Pastrana later broke off negotiations with the FARC, deciding instead to fight. But the FARC would not be cowed. In 2002 it seized Ms. Betancourt, a Colombian senator who was campaigning, somewhat quixotically, for president on a platform of fighting corruption. A year later the guerrillas captured three American military contractors — Keith Stansell, Thomas Howes and Marc Gonsalves — after their small Cessna crashed in the jungle. The kidnappings quickly became an international symbol of Colombian dysfunction and the dangers of tangling with cocaine barons. The American military flew thousands of spy flights over Colombian jungles trying to find the three contractors who had been hired to help find coca fields from the air. Northrop Grumman, their employer, mentioned them at every company meeting and kept vigil for them online. Meanwhile, the ordeal of Ms. Betancourt, the daughter of a diplomat and a beauty queen, pushed Colombia’s conflict to the front pages of Europe’s largest newspapers. Her two children living in Paris rallied support — even as she slowly deteriorated. In letters and interviews since her release, she has described a routine of cruelty that left her at many points without the will to live. Her captors chained her and others by the neck to trees. She rarely changed her clothes. Tropical diseases, long marches through the mountains and a lack of nutritious food eventually shriveled her to a thin post with stringy hair reaching her waist. “It was not treatment that you can give to a living being,” Ms. Betancourt told France 2 television on Thursday. She added: “I wouldn’t have given the treatment I had to an animal, perhaps not even to a plant.” Even as the hostages remained trapped, slowly the impact of increased military budgets and better training began to take hold. Some of the money and technology, helicopters and surveillance tools, came from the American government — an instance of persistent, serious attention in a region that the Bush administration has generally overlooked since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. But under President Uribe, the Colombians also contributed billions of dollars to what they called Plan Colombia. The government has raised taxes twice in recent years to pay for the military buildup. “The U.S. has played an important role, but in the end it’s the Colombian political will — one, to make these steps, and two, pay for them — that has made this happen,” said Mr. DeShazo, who served in 2003 and 2004 as a deputy assistant secretary of state for the Western Hemisphere. American officials agreed. On Wednesday, William R. Brownfield, the American ambassador to Colombia, told reporters in Bogotá that American forces played only a supporting role with intelligence and technical assistance. “This operation was planned and conceived, trained and executed by the armed forces of the Republic of Colombia,” he said, “to whom I express my personal appreciation.” Raid, and Then a Rescue The rescue followed what appeared to be a bold political gamble by Mr. Uribe’s government. In March, Colombian troops crossed into Ecuador, following the FARC without gaining permission from the Ecuadorean government. The result was significant. Mr. Reyes and 24 others were killed in the raid. But the move outraged President Rafael Correa of Ecuador, and led to a tense standoff that became even more heated when Mr. Chávez threatened Mr. Uribe with war if Colombia made a similar incursion into Venezuela. Tension has persisted between Colombia and Venezuela, but Mr. Chávez congratulated Colombia on freeing the captives this week. And in a bit of irony, the Colombians appear to have exploited the trust that had developed between the leftist leader and the rebels. Twice this year Venezuela sent envoys and journalists to pick up hostages in the Colombian jungle. The Colombians had clearly studied video images of the Venezuelan-led operations, which were carried out with help from the Red Cross and broadcast by Telesur, the regional network backed by Mr. Chávez’s government. Though Colombian commanders stressed that the team of soldiers never mentioned Venezuela or tried to pass themselves off as foreigners, the Colombians do appear to have appropriated aspects of the earlier Venezuelan efforts. Planning of the mission, called Operation Checkmate, was meticulous, said Gen. Fredy Padilla de Leon, commander of the Colombia’s armed forces, in an interview in Bogotá on Thursday. Elite commandos took acting classes for a week and a half. Four pilots from Colombia’s air force dressed as civilians; the other eight personnel members on the rescue helicopters included four who appeared to be aid workers; two apparent guerrillas; and two agents disguised as a television journalist and cameraman. The composition of this team closely resembled those sent by Venezuela to pick up hostages in the Colombia earlier this year. And the connection to Venezuela was exploited in other ways, too. Colombian intelligence officials led the guerrillas to believe that they were transporting the captives in two Mi-17 helicopters used by an unnamed international aid group. These aircraft, painted white and black, were intended to resemble helicopters used by Venezuela’s government in two previous hostage negotiations this year. The mission could not have happened, though, without months of painstaking intelligence and counterinsurgency work. Mr. Santos, Colombia’s defense minister, said the Colombian government had penetrated the senior ranks of the FARC, a success that was instrumental in helping persuade the group’s leaders to transfer the hostages. One American official confirmed that at least one mole had been inside the FARC at least a year, and possibly several years. They had managed to collect a trove of knowledge on the hostages’ location. The first details came last April when Jhon Frank Pinchao, a policeman held captive by the FARC for almost nine years, escaped by walking through thick jungle for 17 days, emerging emaciated and wide-eyed to a shocked Colombia. Upon debriefing Mr. Pinchao, intelligence officials began piecing together the area in which the FARC held its captives, southeast of Bogotá in Guaviare, an area where the guerrillas had moved without hindrance from security forces in recent years. After the FARC released two captives in January to envoys of Mr. Chávez, Colombian troops in Guaviare even glimpsed the three American hostages near the Apaporis River. It was February and Mr. Brownfield, the American ambassador, said the Colombians came close to mounting a similar rescue mission then. But it would have been too risky and too quick. An official in Washington said that “a window of opportunity” closed before the Colombia security forces could carry it out. Colombian officials said they feared that the FARC might kill the captives as the guerrillas had done before during botched armed interventions by Colombia’s government. Four other hostages released by the FARC in late February offered further logistical information about the rebel camps and specifically about Cesar, the guerrilla commander, according to Colombian press reports. His real name is reportedly Gerardo Aguilar Ramírez, and he had been ordered by the FARC’s secretariat to guard the captives during the last five years. Cesar was psychologically fragile after the capture earlier this year of Doris Adriana, his companion, and intelligence agents sensed that he was particularly open to praise from superiors, according to a report by Semana, a respected Colombian newsmagazine. The Colombian agents would later exploit this openness by telling him that Mr. Cano, the FARC’s top commander, trusted him to carry out the delivery of the captives, Semana reported. Gathering Insight Further insight into the FARC’s operations was gleaned from computer files belonging to Mr. Reyes, the rebels’ second-in-command. Found on a laptop captured during the raid into Ecuador, the files offered a rare glance into the workings of the FARC and the precariousness of its communications in the past year. “The FARC has had to resort to methods used in the Middle Ages, like human couriers,” General Padilla said. “The messengers carry diskettes, e-mails, U.S.B. chips, but this implies a rudimentary procedure making their communications slow.” Washington was informed as the plan developed over the past few weeks. American officials said they were initially skeptical that the imaginative operation could be pulled off. “There were a lot of people crossing their fingers,” one American official said. “More than one person who looked at this said, ‘My God, this looks like a movie plot.’ ” There were reasons to be skeptical. The mission would require near perfect execution by a military that only a few years ago could rarely be trusted. But this time, the Colombians performed like stars. The unidentified agent successfully imitated the rebel commander’s voice. And when the guerrillas arrived in the early morning light, they were greeted by men wearing Che Guevara T-shirts. They fooled both the hostages and their captors. The agents were so convincing, the general said, that one of the rebels told the supposed cameraman to stop filming so that they could quickly board one of the helicopters. To make the charade especially persuasive, the two agents disguised as guerrillas offered a last-minute suggestion for Cesar: make sure the captives board the helicopter while handcuffed. As the rescue unfolded on Wednesday afternoon, President Bush was in the White House about to be interviewed by a Japanese television crew in the Map Room in advance of his planned trip to Japan for the meeting of leaders of industrialized nations. Mr. Bush, who had been briefed on the operation in the planning stages, was waiting next door. Two of his top advisers — the chief of staff, Joshua B. Bolten, and the national security adviser, Stephen J. Hadley — walked in to tell him the rescue operation had been successful. “Great news,” the president said. American officials said the success validated years of financial assistance and joint training. For the hostages, release meant so much more. Though the FARC still holds between 700 and 2,000 hostages, according to the American Embassy, for these 15, including 12 Colombians, it was finally time to go home. The three Americans arrived on American soil Wednesday after being flown by military plane from Colombia to Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. Military officers gave little detailed information about Mr. Gonsalves, 36, Mr. Howes, who turns 55 on Friday, and Mr. Stansell, 43. But Army medical personnel offered a generally upbeat assessment of their health and mental well-being. Col. Jackie Hayes, the lead doctor on the medical team evaluating the three, said, “I am happy to report they are all in very good physical condition. They are in great spirits. Everything looks good at this time.” Ms. Betancourt, after six and a half years of captivity, seemed remarkably healthy on Thursday, if clearly and understandably emotional. With tears streaming down her face, Ms. Betancourt, 46, wrapped her arms around her son, Lorenzo, 19, and her daughter, Mélanie, 22, and recalled that when she last saw them they were small enough to lift in her arms. Now the daughter Ms. Betancourt remembered as an adolescent girl was “dressed as a woman,” and the once-little boy stood taller than his mother. As she spoke to reporters, her children by her side at last, she marveled at how much they had grown. At one point she turned her head to the right, away from the crush of reporters. Her eyes drifted toward her daughter and she reached over to caress the girl’s face. “They look so different, but they look so the same,” she said. “They’re so beautiful. I think they’re beautiful.” Simon Romero reported from Bogotá, and Damien Cave from Miami. Reporting was contributed by Mark Mazzetti, Eric Schmitt, Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Thom Shanker from Washington, Leslie Wayne from New York, Clifford Krauss from San Antonio and Jenny Carolina González from Bogotá. Foreign Assistance http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/05/world/americas/05colombia.html?_r=1&hp&oref=slogin Freeing Indrid Betancourt New York Times editorial, July 4, 2008 There is every reason to celebrate the daring rescue from FARC guerrillas of the Colombian-French politician Ingrid Betancourt, three American military contractors and 11 members of the Colombian security forces. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia still holds many more hostages. But the operation by undercover Colombian commandos — who tricked the rebels into handing over the captives without a shot — offered further evidence that the guerrilla group is in disarray. President Álvaro Uribe should now capitalize on that disarray and offer the rebels, who long ago traded the business of political liberation for drug trafficking, a political settlement. Ms. Betancourt was raised in France but had returned to Colombia for a run for the presidency when she was seized six years ago. The three American contractors who were held with her were doing anti-narcotics work when their plane was shot down five years ago. The rescue (pulled off with intelligence from the United States) was another coup for Mr. Uribe’s relentless assault on the FARC, which he has waged with billions in American aid. The movement has lost three of its top seven commanders in recent months, and defectors say the forces are increasingly fractured. The FARC is still flush with drug money and still holds more than 700 hostages. The rebels are unlikely to be so easily tricked again, and an all-out assault could cost many lives. Mr. Uribe should instead press for a political settlement. Any deal must require the rebels to fully disarm and get out of the business of drug trafficking and extortion. In exchange, Mr. Uribe could offer amnesty for most guerrillas and the possibility to participate in Colombian politics. Given the huge sums that the United States has spent backing the Colombians’ fight against the FARC, President Bush and Senators John McCain and Barack Obama should now join in congratulating Mr. Uribe — and in urging him to press for a full political victory. Colombia Releases Video of Jungle Rescue by The New York Times, July 5, 2008 ...At a news conference here with dozens of journalists, the government also defended the rescue as a Colombian effort after reports that American and Israeli advisers had taken part. “Not a single foreigner participated,” Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos said. But he acknowledged that the American military had provided a surveillance plane to monitor the operation, as well as tracking technology placed on the helicopter used to spirit the hostages away that could emit distress signals. He also said Israel had helped Colombia reorganize its intelligence services in the past. While Colombia receives more than $600 million a year in security and antinarcotics aid from the United States, any perception of a more in-depth American role in the rescue would be likely to inflame emotions in neighboring countries like Venezuela, where political supporters of President Hugo Chávez openly support the FARC... |

||

|

|||