Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Is There War in Your Ur?by S. Sumathy, Himal, October, 2008

My recollection of Jaffna city is multi-tongued; it records a historical narrative, culled from memory, both dominant and marginal. Jaffna to this day is known as a Dutch city by the historian, while for me it is just home. It is historically a colonial city. Architecturally, it resembles other Dutch cities of the island – Galle at the southernmost tip and Puttalam, on the northwestern coast. “This is doubtless owing to the architecture of its most prominent building – the fort and the bungalows,” wrote H W Cave, a prominent Britisher in Sri Lanka, in 1908. “Other remains of the Dutch architecture in Jaffna are the buildings in Main Street where the gables and the verandas will especially claim notice.” Colonial history actually goes back another century or more. The Kingdom of Jaffna itself is said to have been in establishment from the 11th century or so. The seat of the kingdom skirted today’s city’s limits. As schoolchildren out on vapid educational trips, everyone is taken to see the palace ruins. Actually, the only thing remaining is an ornamental arch, called the Sangili Thoppu, bearing the name of Sangili, the last king of Jaffna. While doing some desultory historical research, I stumbled upon an account suggesting that the arch probably belonged to the headquarters of one Poothathamby Mudaliyar, an administrator during the Dutch times – thus quickly demystifying one’s dreams of a magnificent past, a glorious heritage of royalty and ruins, castles and forts. But the disillusionment is not totally of recent origin. To this day, my hazy recollection of the Thoppu is mixed with the image of a noisy, dirty and cluttered garage that served motorists and cyclists as a repair shop, just behind the Thoppu. For me, a determined cyclist as a schoolgirl, the garage was vastly more useful than the ruins of a distant Tamil king. In our time of war, from the 1970s to the present, the more insistent demands of increasing militancy and the military creates another idiom of martiality. The war in my ur, in my city, is in poetry and in memory. One of the foremost poets of the resistant nationalist era, V I S Jeyapalan, writes in his poem “Rising from the ashes of the dead”: This statue of Sangili oversaw other poignant happenings during the war. Between 1990 and 1995, when Jaffna was under LTTE rule, the administrative centre was shifted to Three Point Junction. People flocked there to haggle, fight and bargain with the administrators of the LTTE regime, in fear and apprehension, to obtain passes to be able to travel to southern Sri Lanka. They would also bargain with the LTTE officials over ‘taxes’, the ‘one sovereign gold’ they had to pay to the Tigers. Three Point Junction and the statue of Sangili are just points in the narrative of wartime history. I lived not far from there – in Nallur, just within the city limits. Not far from the church is the world-renowned Kandaswamy Kovil. The church itself was built on temple land appropriated by the Portuguese, and then taken over by the Dutch in their persecution of Catholics in the area. But the temple grew in prominence during British times, particularly with anti-colonial Shaivite and Tamil revivals, spearheaded by the reformer Arumuga Navalar. Jaffna saw a campaign to open up the temples to ‘untouchable’ castes during the 1960s, and Kandaswamy subsequently opened up as well, unlike other temples set deep in the interior of the Jaffna peninsula. But the dominant Vellala caste would still hold the reins of power. In wartime, both Kandaswamy temple and St James Church would serve as refugee camps. When in October 1987, at the height of the war between the Indian Peace Keeping Force and the LTTE, Rajani Thiranagama wrote in her poem “Letter from Jaffna” – “And thousands and thousands of people/always more than ten thousand/are herded into kovils, churches, and schools/The beautiful sandy precincts of the temple/become nothing/but one big shit dump” – she was referring to Kandaswamy. I sometimes wonder to what extent caste barriers were broken in the proximity brought about by war, by the sense of solidarity brought about by suffering. The memory of war goes a long way back in Jaffna. It precedes our current war, spilling over into memories of other wars, other people’s struggles. Jaffna Fort: what does its memory evoke? The fort is not part of the lived reality for many people, unless of course one thinks of prisoners incarcerated in the prison that was housed inside the fort. The Jaffna Fort, reconstructed by the Dutch from an old Portuguese fort, is considered to be the finest of the Dutch forts in all of Asia. The original structure was built by the Portuguese, seemingly in defiance of the king of Jaffna, who had given permission only to construct a building – but had not bargained on what would become a well-fortified garrison. After the capture of Jaffna by the Dutch, this structure was reconfigured as a Dutch fort, housing residences and a church serving the Dutch rulers. The market lay off to one side of the fort. During British times, from 1872 onwards, the market area began to take over the fort in importance, replacing the British and the Europeans with the overflowing humanity of the ‘natives’. Up until the intensification of the war, during the 1990s, the market remained a central point, a place marked by ‘low life’, the chatter and cursing of fisherwomen, and a place of adventure for a middle-class teenager setting out on rather timid expeditions into city life. But nothing was more shocking than the realisation that the imposing structure of Our Lady of Miracles, near the fish market, was actually built on land belonging to a mosque that is no longer there. Still, the fort was in many ways symbolic of Jaffna city. As children during peace time, we were taken on tours to see it. But it also housed a modern prison, housing inmates from the local population as well as those from far away. On the night of 4 April 1971, I was returning with my parents from the esplanade encircling the fort, after watching a passion play performed by the local Catholic community. We watched from afar this gruelling pageant, the entourage following Jesus winding its way up to Golgotha. It was my first experience of watching a passion play live, and my last. On our way back home, we were stopped by a passing neighbour who gave us more pressing news, more exciting than the passion of Christ. At that time, I did not realise the import of the message: the prison housing Sinhala political prisoners – notably Rohana Wijeweera, the leader of the militant Marxist party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) – had been attacked by insurgents. But the police had turned the floodlights, which had been used to illuminate the passion play, onto the fort, and had been able to quell the attack. Between 30 and 40 insurgents, who had travelled from Colombo for this mission, had been killed in the attack. We would later realise that this marked the beginning of the insurrection of 1971, the southern uprising of the Sinhala youth. Jaffna too was part of it, though it watched from the sidelines. Wijeweera was later killed by state forces in a raid on his hideout in 1989, in the days of the second JVP uprising. The esplanade would be witness to many other events, too, all part of a conflict that would eventually sneak up on the Jaffna public. In January 1974, the International Tamil Research Conference was held in Jaffna city. The conference itself was a tame and vapid affair of international scholars meeting to ponder matters of great unimportance. But we also witnessed a carnival of emotion, a great outpouring of nationalist sentiment by the people, as they voluntarily adorned the streets with pandals and other decorative paraphernalia. On the final day of the conference, 10 January, at a public rally held at the esplanade, for no apparent reason the police suddenly opened fire and tear-gassed the crowd, creating a stampede and an accidental electrocution in which several people died. The incident, though today consigned to the dust heap of history, became one of the cardinal points in the narrative of ‘our war’. This was soon to be overtaken by the burning of the Jaffna Public Library, in 1981.

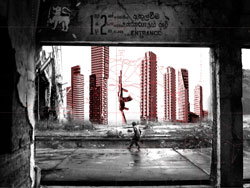

Why has this act of aggression become so much more important than many other such incidents, by either the state forces or the militant movements, namely the LTTE? Are the story and its telling somehow linked to the political economy of the city and the peninsula? Jaffna is a non-industrialised agricultural area, and in its heyday it was dependent on remittances from its (lower-) middle-class workforce in the south. Surrounded by agricultural lands, the city’s main focus was educational. The schools of Jaffna, initiated first by American missionaries during the 19th century, were eventually taken up by revivalists and liberal leftwing anti-colonialists, such as the Jaffna Youth Congress. Soon, these institutions began to attract students from southern Sri Lanka, particularly from elite families. Jaffna took great pride in what it saw as its legacy to the country – education. Its middle classes prided themselves on being both cultured and educated. The burning of the Jaffna Library was seen as state aggression, hitting out at precisely this focus of community pride. A Catholic priest collapsed and died in shock upon hearing of the event, and the act likewise became a pivotal emotional point in the history of victimisation of our war. While cultural activity surrounding the burning has been manifold, I would like to cite just one piece by the celebrated poet and scholar M A Nuhman, who at the time was a lecturer at the University of Jaffna. The old spills over into the new. The old and new structures of the Jaffna Library are Mughal in form, with, interestingly, a statue of the Hindu goddess Saraswathi in front. This inevitably conjures up memories of the Muslim areas of Jaffna city, replete with their Mughal mosques, high domes and arches. This also brings me to one of the most troubling events of ‘our war’ – the LTTE’s eviction of Muslims from the city, the peninsula and the entire Northern Province in 1990. (In a chilling ‘reenactment’ five years later to the month, in October 1995, the LTTE would drive out about 500,000 Tamils from the northern peninsula and the city at the approach of the Sri Lankan Army, now referred to as the ‘exodus.’) Jaffna city, like many others, was a city of minority communities, made up of a majority of Catholics, while the majority of Muslims on the peninsula were concentrated largely within the city premises. At the same time, though, our memory of war (and peace) has blocked out the memory of how the Muslim community had also originally settled near the Kandaswamy Temple. During the Dutch period, those who had worshipped in the area were tricked and ousted by their Hindu neighbours. In all of the stories of victimisation that children in Jaffna grew up with, one would never hear about how, for instance, slaughtered pigs were maliciously thrust into Muslim wells. I was alerted to this by a young Muslim woman who was evicted from the city in 1990. “It has happened before,” she told me. “What is the guarantee it will not happen again?” Nationalist history has no place for these unseemly happenings. Nor does it have a place for Muslims in the record of memories, of victimisation and victories. The Muslims were eventually pushed to the margins of Jaffna city, on the other side of Navalar Road, named after the Tamil revivalist Arumuga Navalar. Notorious for his religious hostility and hide bound casteism, Navalar is in many ways a discredited figure in Tamil literary circles today. Nonetheless, a statue of Navalar still adorns the corner of the street near the temple. For me, that statue is a potent part of the dominant narrative of history making – the rebuilding of the Jaffna Public Library, the Saraswathi statue and attendant stories, and the eviction of the Muslims in 1990 at two hours’ notice. Jeyapalan’s vaulting nationalist poem cited above includes compulsive writing on the eviction: Why do I recall this when I sit down to write about Jaffna, a place that I still claim to be my own, though I left it 18 years ago, not knowing whether I would return? I have gone back only once since, a fleeting two-day visit during the Ceasefire Agreement of 2002. I went under cover of attending a workshop for academics. It hardly resembled the bustling city that I knew as a teenager, when I trundled around on a beat-up bicycle; or later in the mid-1980s, when I nonchalantly but carefully negotiated the many checkpoints that had sprung up all over, of the Sri Lankan army, the IPKF and the militants. But my nostalgic memory is not of a promise of a future, potent and portent. It is of a dying moment. My memory of return is overlaid with the shock of discovering a city overgrown with shrub vegetation, roads that had shrunk to narrow alleyways. As I landed in the town centre I was completely disoriented, like the returning expatriate in In Search of a Road. As the three-wheeler wended its way down Main Street, I fumbled with my directions, not knowing where I was. Main Street, the busy thoroughfare that connected the city to Kandy Road (the highway built by the British to connect Jaffna to the south), was inextricably deserted. So, in my inability to recover the Jaffna of my war, I go back to memories of happier times and sadder times. I think of the great Jaffna scholar, A J Canagaratna. For me and many other displaced peoples of Jaffna, A J signified the last strand of hope, of intellectual fervour, of cosmopolitanism, of quiet and undying dissent, and of the links between the past, the present and the future. When he died, I knew that my last tenuous link with Jaffna had snapped. I will go back to Jaffna someday. I will go back to Main Street again, but never to visit A J. And so, we can close this rumination in tribute to a friend, doing so in the hope of memorialising an ethos of dominance and displacement, to point to a liminality of a city besieged by war and hoping for peace. S Sumathy is involved with theatre and filmmaking while teaching in the Department of English at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. |

|||

|

||||

The title is taken from a query articulated by a young participant at a workshop last year for displaced youths, both Tamil and Muslim, from the north and the east of Sri Lanka. The workshop was part of an ongoing research project, during which participants had to interview a partner on the other person’s place of birth or dwelling. For this young man from Jaffna, the northernmost city in Sri Lanka, the question encompassed all that he could ask of life. In Tamil, ur means land, one’s own place. Is there war in your place? But is that all that Jaffna is? What do I recall of Jaffna, which is my ur as well? What could I recall that could have meaning for those who see themselves as Southasian? Is there war in your ur, too? In other Southasian countries? In other countries in the world? Will they recognise Jaffna in their own cities?

The title is taken from a query articulated by a young participant at a workshop last year for displaced youths, both Tamil and Muslim, from the north and the east of Sri Lanka. The workshop was part of an ongoing research project, during which participants had to interview a partner on the other person’s place of birth or dwelling. For this young man from Jaffna, the northernmost city in Sri Lanka, the question encompassed all that he could ask of life. In Tamil, ur means land, one’s own place. Is there war in your place? But is that all that Jaffna is? What do I recall of Jaffna, which is my ur as well? What could I recall that could have meaning for those who see themselves as Southasian? Is there war in your ur, too? In other Southasian countries? In other countries in the world? Will they recognise Jaffna in their own cities?