Ilankai Tamil Sangam28th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

The Indo-LTTE WarAn Anthology, Part X1The Maldives Plot by PLOTE MercenariesNovember 17, 2008

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha Jawarharlal Nehru (1889-1964), India’s first prime minister, was a keen historian whose down-to-earth observations have been rather underrated by the academics who are India specialists. One possible reason has been that Nehru’s books were mostly written while he was serving a sentence in jail, and were devoid of the usual bells and whistles that decorate academic tomes. Here is one paragraph of Nehru’s incisive thoughts on the quality of journalism practised by The Hindu newspaper in the 1930s.

There you have it from the mind of freedom fighter Nehru, characterizing The Hindu as a “paper of the bourgeois, comfortably settled in life.” That was during the British colonial days in 1936. Five decades later, how the same Madras Hindu newspaper covered the Indo-LTTE war, initiated by Nehru’s grandson Rajiv, is of some interest. For the record, I reproduce a letter that appeared 20 years ago in the Tamil Times monthly (London) of October 1988. This letter incorporated a letter of mine (that had appeared in the Hindu newspaper of August 19, 1988). I had sent my letter to the Hindu newspaper office from Tokyo, but until the appearance of this Tamil Times letter by “S. Kurushetran” from Madras, I was unaware of its publication in the Hindu newspaper. I could infer that “S. Kurushetran” was a pseudonym used by S. Sivanayagam, the ranking Eelam journalist who was then living in Madras and who was also a regular contributor to the Tamil Times monthly at that time. Here is the complete reproduction of this epistle from “S. Kurushetran”. The dots appearing in the text are as in the original. ‘The Hindu’ and Editorial Decorum [by S.Kurushetran; Tamil Times, Oct. 1988, p. 12] Someone had to say it, and Tamil Times contributor Mr Sachi Sri Kantha of Tokyo has said it. In a letter to the Editor in the Hindu (Aug.19), which the paper was gracious enough to publish, Mr Sachi Sri Kantha wrote:

As Mr Sachi Sri Kantha has said, The Hindu has changed direction after July 29, 1987. Among the depressing fall outs of the accord, this has been one. While Mr Sachi Sri Kantha has in this instance confined himself to the aberrations in The Hindu’s comments, there is another aspect which calls for greater concern, and that is the paper’s growing lack of decorum in the reporting of the news itself; a tendency that cannot do any good to a paper that had acquired an international reputation over the years. Comment is free, but facts are sacred in responsible journalism. As an example of motivated reporting on the part of The Hindu, we present here the reports of the same incident carried in the Indian Express of Aug. 14, and in The Hindu of the same day. The Indian Express reported thus:

In contrast, The Hindu version reads thus:

The report was headlined – LTTE BID FOILED. According to the Express report, and in the minds of all intelligent and objective readers, the sequence of events was very clear. The LTTE blew up the track, preventing the train from proceeding. The IPKF went to the spot to restore the track and in the process became victims of a LTTE-triggered landmine. It would be straining the credulity of Sri Lankan readers (both Tamils and Sinhalese) that the LTTE could be so foolish as to blow up a train carrying hundreds of Tamil passengers; to ask readers to believe that they are politically ‘intransigent’ is one thing; but to tell them that the LTTE is capable of crass stupidity is something which should be told to the Marines. But the sad truth is, The Hindu would have succeeded in misleading lakhs of Indian readers who depend upon the paper alone for their information. The tragedy of The Hindu is the tragedy of newspaper editors who allow themselves to be sucked into the decision-making processes of their governments! ***** That the jaundice-eyed journalism of The Hindu condemned by S. Sivanayagam in 1988 has been critiqued by none other than Jawaharlal Nehru in the 1930s as the “paper of the bourgeois, comfortably settled in life” is a matter of pertinence even now. Listed below, for Part 11 of this anthology, are 11 news reports and commentaries that appeared in November 1988. Quite of a few items focus on a side-show of a Maldives coup attempt staged by PLOTE mercenaries to topple the then government of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, who lost to Mohamed Nasheed, in a run-off of the presidential election held on Oct.28.. (1) Anonymous: Killed - Tudor Keerthinanda and N.Sivanandasundaram. Asiaweek, Nov.4, 1988, p. 55. (2) Edward W. Desmond: Jayewardene Under the Gun. Time, Nov.7, 1988, p. 11. (3) Anonymous: A Bloody Prelude to the Polls. Asiaweek, Nov.11, 1988, p. 33. (4) India Correspondent: The Meaning of the word Raj. Economist, Nov.12, 1988, pp.22-23. (5) Sri Lanka Corrospondent: No Place for Sunbathing. Economist, Nov.12, 1988, p. 23. (6) William R. Doerner: Maldive Islands – Heading Them Off at the Atoll. Time, Nov.14, 1988, p. 27. (7) Anonymous: Maldives – The Coup That Failed. Asiaweek, Nov.18, 1988, pp. 37-38. (8) Manik de Silva: Terror Stalks the Lanka. Far Eastern Economic Review, Nov.24, 1988, pp. 38-39. (9) Anonymous: A Nation on the Brink. Asiaweek, Nov.25, 1988, pp. 22 & 27-28. (10) Sri Lanka Correspondent: The Tamils Defy the Tigers. Economist, Nov.26, 1988, pp. 26 and 29. (11) Marguerite Johnson: Assassination and Intimidation. Time, Nov.28, 1988, p.13.

Killed [Anonymous; Asiaweek, November 4, 1988, p. 55] Killed: Tudor Keerthinanda, prominent Sri Lankan lawyer and senior leader of the ruling United National Party; by unidentified assailants who threw a bomb and shot at his car; in Colombo Oct. 21. Keerthinanda, a UNP policy-making committee member, was killed instantly. Police suspect the attack was organised by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front), a Sinhalese militant group believed involved in earlier killings of UNP leaders. The ambush came a day after the government declared a one-week halt to its operations against the group, a conciliatory gesture intended to make peace with the JVP before the presidential election in mid-December. Killed: N. Sivanandasundaram, a representative of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a militant Tamil separatist group in Sri Lanka; by unidentified gunmen; at Vallai Veli village in the northern Jaffna peninsula Oct. 21. Sivanandasundaram was a Tiger nominee to an interim council proposed by the government for the new Northeastern Province, part of a peace plan the militants have now rejected. *****

Jayewardene Under the Gun [Edward W. Desmond; Time, November 7, 1988, p. 11] Dissolve Parliament immediately. Name an interim government. Call elections as soon as possible. The demands that four prominent Buddhist monks listed in a letter to President Junius R. Jayewardene last week seemed outlandish, considering that his United National Party (UNP) controls 85% of the 158 seats in Parliament. Increasingly, though, it is not Jayewardene, 82, or Parliament that is setting policy in Sri Lanka but gunmen from the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), who have taken more than 500 lives over the past 15 months and all but paralyzed the south of the island. Their goal: to push Jayewardene and his party from power. The monks’ petition sought to persuade Jayewardene to agree to at least some of the JVP’s terms in the hope of stopping the cycle of violence. Five days later, in a meeting with seven opposition party leaders, Jayewardene yielded, but on one condition: the JVP must halt its violent activity immediately. Toward that end the President declared that for a week police and the army would cease operations against the militants. If they responded in kind, said Jayewardene, he would dissolve Parliament, appoint an interim government and order national elections. ‘We are not backing down,’ said Ranil Wickremesinghe, Minister of Education. ‘We are throwing the onus on them.’ However generous the gesture, Sri Lanka’s problems are much too complex to be settled by a quick fix. The conflict pressing on Jayewardene last week involves the island’s Sinhalese majority. That confrontation was triggered, in part, by Jayewardene’s decision in 1987 to solicit Indian military assistance in the northern and eastern reaches of the island to put down a rebellion by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam; they have been fighting for five years to win an independent homeland for the Tamils, who make up 12.5% of Sri Lanka’s population. Sinhalese complained bitterly that Jayewardene had sold out to India, Sri Lanka’s ancient foe, and the JVP, until then a relatively quiescent group, suddenly emerged as the violent champion of Sinhalese extremism. Through a combination of shrewd political tactics and terror, the JVP almost overnight became a decisive player in Sri Lanka’s politics, even though its members are underground and its leader, Rohana Wijeweera, 45, a medical-school dropout, has not been seen in public for more than five years. Shortly after Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Jayewardene signed the 1987 accord, JVP hit men came close to killing Jayewardene in a grenade attack in the Parliament building. Since then, more than 350 UNP officials and workers have been assassinated, including the party’s chairman, Harsha Abeywardene. The heart of JVP support lies in southern areas, where poverty has worsened during Jayewardene’s eleven years in power, even as the rest of the country enjoyed unprecedented economic growth. In Hambantota district, more than 70% of the 477,000 inhabitants receive food stamps. Yet in recent years the government has cut back spending there and has launched heavy-handed retaliatory crackdowns, some of them against demonstrators, that have claimed as many as 100 lives – a surefire recipe for creating recruits for the militants. Like most of the south, Hambantota is a stronghold of Sinhalese nationalism, a tradition with such vibrancy that Dutugemunu, a Sinhalese king who drove a Tamil rival off the island 2,000 years ago, is discussed as if he lived yesterday. Says Colonel Vipul Boteju, an army officer in the area: ‘About 60% of the youths here are either JVPers or sympathizers.’ That is not the case elsewhere, especially in more prosperous districts, but the JVP’s calls for strikes have brought many towns, including even the capital of Colombo, to a standstill. Ensuring that there is cooperation is the job of 2,000 JVP cadres, who are ready to kill anyone who fails to heed menacing posters and pamphlets calling for work stoppages. Jayewardene’s promise more than a year ago to ‘eliminate’ the JVP has metamorphosed into repeated attempts to placate them. He lifted a ban on the organization in May, released a few detained JVP leaders, and two weeks ago announced presidential elections for next month. He also picked Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa as his successor, believing him to be acceptable to the JVP. Premadasa opposed the Indo-Sri Lanka accord and has made it clear that he would send the 70,000 Indian troops home. But that line has apparently not impressed the JVP. When Jayewardene offered his enemies a week-long ceasefire, JVP cadres responded with another round of killing. The UNP’s elected opposition, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, led by former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, has also been trying to woo the JVP and has succeeded in bringing it into a loose alliance with six political opposition groups. But the JVP has proved an uncompromising partner. On five occasions its threats have disrupted rallies for Bandaranaike’s party and some opposition leaders are reportedly seeking police protection. Frustration and anger over the JVP’s bloody tactics have reached such a pitch that government and opposition leaders are even thinking of working together to rein in the gunmen. That possibility looked a little more likely at week’s end after the JVP declared it would accept Jayewardene’s ceasefire offer – but only after he has acted on its demands. That response left Sri Lankans wondering whether the JVP is willing to play by democratic rules at all, or if in the end it is committed to pursuing power from the barrel of a gun. [Reported by Qadri Ismail and Anita Pratap/ Colombo] ***** A Bloody Prelude to the Polls [Anonymous; Asiaweek, November 11, 1988, p. 33.] Early on Oct.22 farmer Henchilage Jinadasa stepped into the jungle in Wellawaya, 140 km southeast of Colombo. Moments later he emerged screaming. He had stumbled on the partially burnt corpses of three students from Ratnapura, 75 km away. A post-mortem showed that the young men were brutally tortured before they were killed. They had been campaign workers for the opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) in a Ratnapura by-election a few weeks earlier. Their candidate had won the bitterly fought contest against Susantha Punchinilame of the ruling United National Party (UNP), who was arrested after the bodies were found. Their murders are part of a rising tide of violence that threatens to derail Sri Lanka’s Dec.19 presidential election. Although several of the victims appeared to have been involved in local vendettas with ruling party politicians, the more serious threat to the polls is the militant Sinhalese group Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), which is accused of killing more than 500 ruling party leaders and supporters. Despite the JVP’s reputation, it was included in an eight-party opposition alliance that named SLFP chief and ex-prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike as its presidential candidate. The UNP countered by nominating Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, whose conciliatory line towards the extremist group has not stopped attacks against his fellow legislators. But just three weeks after forging the alliance, the JVP turned against its partners and instructed them to boycott the presidential poll. In southern Sri Lanka, posters went up threatening SLFP organizers with harsh punishment if they engaged in political activity. An SLFP rally in the Southeastern Province was disrupted Oct. 23 by an alleged JVP bomb blast as Bandaranaike address the crowd. The JVP wants President Junius Jayewardene to dissolve Parliament and hand power to a caretaker government. Jayewardene, 82, who is retiring after eleven years as president, met opposition leaders in an attempt to defuse the crisis. Last week he agreed to step down, to dissolve Parliament Nov.6 and to set a date for general elections. Jayewardene proposed a multi-party cabinet to oversee elections, and said he would lift the state of emergency, release all political prisoners and cease military operations. That would include activities of the Indian peacekeeping force policing a July 1987 accord with New Delhi – branded a ‘sellout’ by the JVP – that gives Sri Lanka’s minority Tamils greater autonomy. Jayewardene’s condition: ‘a permanent ceasefire and abandoning of violence’ by the JVP. The JVP rejected the offer, insisting that its demands be met first. But the SLFP was said to be seriously considering Jayewardene’s proposal, which could lead to a split in the opposition alliance. Observes a political analyst: ‘The JVP wants power for the sake of power, and they aren’t interested in sharing it. The only option available for a government and a democratic opposition would be to join hands and fight terrorism together.’ ***** The Meaning of the word Raj [India Correspondent; Economist, November 12, 1988, pp. 22-23.] The snap decision India made to stop the attempted coup in the Maldives, on the heels of its Sri Lankan intervention last year, shows the scale of its ambitions in South Asia. India says it wants to preserve ‘regional stability’. This is the sort of phrase that is used on such occasions. Trouble in Maldives poses no threat to Indian security, of course; but Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s government does not like the idea of coups. The week’s events showed, impressively, that India has the means to impose its will. The prime minister came to know of the coup attempt at 8.30 on the morning of November 3rd, when he received a telephone call from an aide of the Maldivian president, Mr Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. The first transport aircraft, carrying 150 paratroops, landed in the Maldives less than 14 hours later, having flown, 1,700 miles from a base south of Delhi. The United States, which had been in touch with Mr Gandhi, was happy for India to fix things in the Maldives. A similar view was taken by Russia and by Britain, the former colonial power, which used to have an air base on Gan, the southernmost island of the Maldives. Having Mr Reagan, Mr Gorbachev and Mrs Thatcher cheering him on must have bemused Mr Gandhi. It is a lot better than the accusations he hears from Sri Lanka. The trouble in Sri Lanka, unlike that in the Maldives, does threaten Indian security. Ever since 1983, when the Tamil campaign for a separate state on the island began in earnest, India has wanted the Sri Lankan government to give the Tamils a generous measure of autonomy. It does not want to risk upsetting the 55 m Tamils who live in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which in the 1950s had a strong separatist movement, called the Dravida Kazhagam. Although this movement failed, one or other of its more legitimate offshoots, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and the All-India Anna DMK, has been ruling Tamil Nadu continuously since 1967. The Sri Lankan government did offer its Tamils a good whack of autonomy, and the Indians sent a military force to the island last year to back up the offer. When the Tamil Tiger guerrillas refused to accept the deal, Mr Gandhi did not hesitate to send Indian troops into battle against them. They are still there, killing Tigers and getting killed. They must feel envious of their comrades’ short, sharp campaign against the Maldivian would-be coup-makers. Back in 1971 Indian intervened in the affairs of another of its neighbours, East Pakistan. That country, which is now Bangladesh, was then in a state of civil war with the western portion of Pakistan. Some 9m East Pakistanis, mostly Hindus who feared persecution from the Muslims of their homeland, had fled into the adjoining Indian state of West Bengal. West Bengal was desperately poor and could hardly feed itself, let alone the refugees. It had a communist government that thrived on Bengali nationalism. As India saw it, something had to be done to restore stability – that word again – to East Pakistan. It sent its army in, ending the civil war and guaranteeing independence for Bangladesh. Pakistan, ever suspicious of and hostile to India, has never forgiven it for that. The Maldives may accept India as a protective uncle. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have no option but to acknowledge its strength. The real test of India’s aim to be the regional superpower will be how it handles Pakistan. ***** No Place for Sunbathing [Sri Lanka Correspondent; Economist, November 12, 1988, p. 23.] Foreign tourists were advised by the Sri Lankan government this week to go home. The place is unsafe. This will be no surprise to people who wonder why anyone should choose a country at civil war for a holiday. But until now the palm-edged beaches of the island’s south-west coast have been untouched by the troubles of the north and east, where Tamil guerrillas are fighting for a separate state. Now the holiday coast is endangered, not by the Tamils, but by the anti-Tamil reaction: a group of extremists drawn from the country’s majority, the Sinhalese. The group, which is known by its initials JVP, for Janatha Vimukti Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front), preaches revolutionary Marxism. It tried an insurrection in 1971, which was put down by the government of Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, helped by India. It has revived, and has confusingly mixed its Trotskyism with bloody nationalism, since last year’s signing of the Indian-Sri Lankan accord on the Tamil question. The Indian soldiers who came to the island to enforce the peace between Tamils and Sinhalese are servants of imperialism, according to the Front. President Junius Jayewardene and his ministers are ‘traitors’ for allowing the Indians in. Since the Indian intervention the JVP’s military wing has killed more than 500 government supporters, officials and members of the security forces. The government lifted the ban on the JVP as a political party, hoping it would emerge from the underground and join the democratic process. The move failed, as have a series of other concessions aimed at blunting the extremists’ appeal to Sinhalese: special aid for the south, the release of detainees, the announcement of a date for a new presidential election, the selection of an anti-accord presidential candidate, finally the offer of a parliamentary election too. The Front’s aim is to create such unrest that the government will be unable to bring peace to the island, and the government’s candidate will be defeated in the presidential poll on December 19th. It is working. The government is getting the blame for the chaos caused by the Front: the food and fuel shortages, power cuts and paralysed transport. Now 8,000 foreign holiday makers, one of the country’s few remaining sources of foreign exchange, are going home, most of them. Even the stalwart ones who stay may find their holidays ruined. Most members of the hotels’ staff have been frightened away.

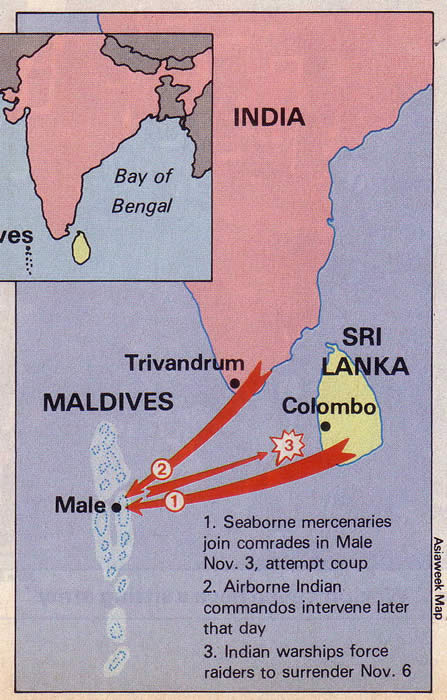

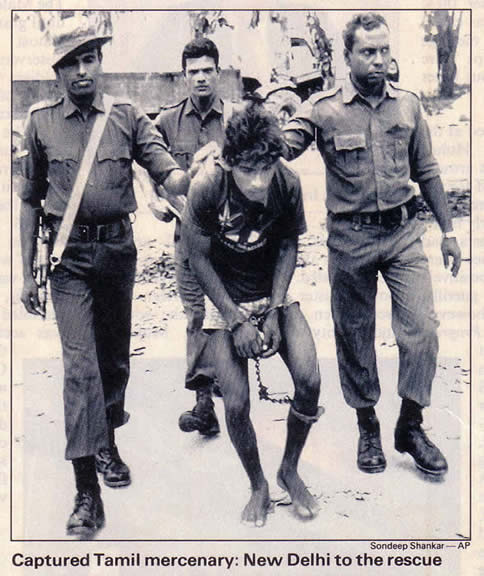

Maldive Islands – Heading Them Off at the Atoll [William R. Doerner; Time, November 14, 1988, p. 27.] The prospect of a military invasion of the Republic of Maldives would seem to be almost as remote as the Indian Ocean archipelago itself. Some 1,200 coral islands that together make up only 115 sq.mi.of land, the country lies several hundred miles southwest of India and Sri Lanka. Its 195,000 citizens, most of them Sunni Muslims, earn their living largely from fishing and tourism. Possession of guns is outlawed, except for the fewer than 2,000 lightly armed members of the National Security Service, and violence is virtually unknown. Yet last week Maldives’ capital island of Male was invaded, briefly but brutally, in an unsuccessful coup attempt carried out by foreign mercenaries. The raiders, who numbered only about 60, struck before dawn on Thursday, landing aboard speedboats from a small freighter moored offshore. Armed with rocket launchers, mortars and automatic rifles, they quickly seized almost total control of the 370-acre coral atoll, firing at civilians who came out of their homes to investigate. Among the first killed were early-morning joggers who stumbled onto the intruders. Many of the island’s most prominent buildings, including its gold-domed mosque, were severely scarred by hours of gunfire. The only major government building that remained secure during the assault was the headquarters of the security service, and it came under heavy fire. The apparent target was President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, 50, member of a well known Maldivian family who was re-elected in September to a third five-year term. The rebels literally had the government on the run: Gayoom and several members of his Cabinet fled from house to house to avoid capture during the 18-hour invasion. Nearly all the invaders were believed to be former Tamil separatist guerrillas from Sri Lanka, apparently in the pay of Maldivian elements hostile to Gayoom. The President issued pleas for military intervention from India and the US as well as Britain, which held Maldives as a protectorate from 1887 until 1965. Washington and London took the request under consideration. But before they could make a decision, New Delhi moved fast. Following an emergency Cabinet meeting, Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi dispatched some 1,600 troops to restore order on Male and commanded navy warships to head toward Maldivian waters. Para-troopers arrived less than twelve hours later, landing aboard two Soviet-built IL-76 transport aircraft at the national airport on Hulule, a few hundred yards off Male. Within minutes the mercenaries began fleeing the capital in their small boats, racing back to their mother ship. On Sunday the mercenaries surrendered after an Indian frigate fired on the freighter. The invaders left at least 30 dead, most of them civilians, and nearly 100 injured. According to Foreign Minister Fathulla Jameel, several eyewitnesses identified as the leader of the band a once prominent Maldivian businessman named Abdulla Lutefi, who currently operates a farm near the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo. Several years ago, Lutefi was arrested for entering Maldives with a firearm, apparently in an attempt to overthrow Ibrahim Nasir, Gayoom’s predecessor as Presiddent. Sri Lankan and Maldividian authorities suspect that Lutefi may have hired the Tamil mercenaries, many of whom have become increasingly inactive since India sent army troops to Sri Lanka to quell the separatist movement in 1987. Gandhi clearly intended India’s quick response to underscore New Delhi’s growing military role in southern Asia. He may have the chance to make the point again. Domestic dissatisfaction with the Gayoom regime, which does not allow opposition, is substantial, and the Maldives may attract other visitors with more on their minds than scuba diving. *****

Maldives – The Coup That Failed [Anonymous; Asiaweek, November 18, 1988, pp.37-38.]

Abdullah Raffi wondered sleepily who was lighting firecrackers so early in the morning. He did not know of any celebration planned for that Thursday in Male, the capital of the Maldives. The trader grumpily got out of bed and went downstairs to his waterfront shop. ‘Only when I opened the door did I realise I was hearing the sound of gunfire,’ he later told a newspaper in neighbouring Sri Lanka. Heavily armed soldiers in camouflage were running towards the headquarters of the National Security Service, the Maldivian paramilitary police force, just 400 metres away. Raffi was one of the lucky few to witness the landing and stay alive. Thirteen civilians, some of them youngsters out jogging, were shot dead by the invaders. Thus did death and violence come to the tiny group of Indian Ocean atolls (pop. 207,000, mostly Muslim) whose sun-drenched beaches and clear waters have helped make the archipelago a tourist paradise. The objective of the raiders: to topple the government of President Maumoon Gayoom, 51, who was recently elected to a third term. The ring leader was identified as Abdullah Luthfi, a Colombo-based Maldivian businessman. Luthfi reportedly hired some 150 militants of a separatist group in Sri Lanka, the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE). ‘They are doing nothing; they have no jobs,’ said D. Siddharthan, himself a PLOTE member, but a moderate. ‘Anyone can recruit 100 to 200 any day.’ But the Nov.3 coup attempt failed. Gayoom and most of his cabinet stayed safe inside the well-fortified Security Service building. When crack commandos from India arrived that night, Luthfi and most of his mercenaries had already fled in a freighter, taking with them Maldivian Transport Minister Ahmed Mujuthaba, his wife and 30 other hostages. Indian warships chased the boat but it could not be immediately boarded – the plotters threatened to kill their prisoners. The stalemate was broken Nov.6, when the Indians opened fire and crippled the ship. Some 46 men, including Luthfi, finally surrendered. Four of the hostages were believed killed, while the Maldivian minister was injured. According to Sri Lankan intelligence sources, Luthfi promised the Tamil fighters $2.5 million and a permanent base in the Maldives. The deal struck, he arranged for most of the men to take up employment in the capital several weeks before the attack. The rest boarded boats bound for Male on the day of the invasion. Reaching the island in the early dawn, they quickly joined up with their comrades and stormed the Security building, the presidential palace and other government installations. However, the gunning of early risers alerted Maldivian officers, who had Gayoom and his ministers swiftly brought to Security headquarters. The bunker-type building had recently been equipped with its own power generators and communication equipment. Luthfi’s forces swiftly overran their targets, including the palace. But the Security headquarters was valiantly defended; several Maldivian soldiers died in the exchange of fire. Diplomats in Colombo say Luthfi himself led the palace assault. He began issuing proclamations, ordering the surrender of Gayoom and the Maldivian forces. At one point, Luthfi declared that more than 2,000 hostages would be killed if Gayoom did not give up. Inside his refuge, the beleaguered president was in contact with the outside world. His first call at around ten o’clock Thursday morning was to James Spain, the US ambassador to Sri Lanka and non-resident consul to the Maldives. Gayoom wanted to know whether the Americans could send a rapid deployment force from their base in the island of Diego Garcia, just 804 km from Male. The ambassador said he had to first consult the US State Department in Washington. Gayoom then got in touch with his envoy to the UN, Hussein Manikfu, instructing him to ask for military help from the US, Britain, Sri Lanka, India and several other Asian countries. The Americans ruled out direct intervention, but State Department spokesman Charles Redman said Washington was closely watching events ‘with an eye to what assistance we might be able to provide.’ Both the US and Britain reportedly worked quietly to coordinate with India when it decided to send its forces. Malaysia, a staunch friend of the Maldives, was also asked for help. Its navy was immediately alerted, but as the Malaysian Foreign Ministry later explained, it would have taken three or four days for Malaysian warships to reach the Maldives. At about the same time, in the country’s only other mission abroad, Maldivian High Commissioner to Sri Lanka Ahmed Abdullah lodged an urgent appeal with Foreign Minister Shaul Hameed, who rushed to see President Junius Jayewardene. The Sri Lankan military, anticipating the request, had already drawn up a plan. About 85 commandos were ordered taken to Ratmalana Air Field for airlifting to Male. But later that day, after three hours of waiting, the operation was called off. New Delhi sent Colombo a message saying 1,600 of its crack troops were already flying to Male from various bases in India. The Indian commandos landed at the international airport on Hulule Island, 3 km from Male, at around 10 pm. They immediately took off for the capital in assault craft, but the mercenaries were already retreating. By the early hours of the following day, the rescuers had regained Male. Four mercenaries were captured, one of whom has been positively identified in Colombo as a PLOTE guerilla. Luthfi and many of his raiders, however, managed to board the freighter Progress Light with their hostages. When it was spotted heading for southern Sri Lanka, the Indian warship INS Betwa gave chase while another more sophisticated vessel, the helicopter-equipped INS Godavari, moved to cut it off. The fleeing freighter was soon captured. A four-man team of Maldivian negotiators flew to the Godavari, but Luthfi and the Tamils refused to parley. They insisted that talks should be held in Colombo in the presence of international observers. The stand-off continued until President Jayewardene declared that under no circumstances would the freighter be allowed into his country. A little before midnight on Saturday, the mood of the mercenaries turned ugly. Two of the hostages had been killed, they announced, and more would die if they were not allowed to land in Colombo. The Indians stood firm. The Progress Light could go to India, but not to Sri Lanka. The freighter began heading for Sri Lanka anyway. At 1 am Sunday, the Godavari fired warning shots. The freighter was about 85 km from Colombo when the warship opened fire, hitting it below the water line. Helicopters buzzed the boat and fired rockets. At 9:25 in the morning, the mercenaries finally gave up. Forty six mercenaries, including Luthfi and his Maldivian deputy known as Nasir, were arrested. The freed Maldivian transport minister and some fourteen others were taken to hospital in the southern Indian city of Trivandrum. Mujuthaba was reported in good condition. In retrospect, the attempted takeover was not all that unpredictable. Like many island states, the Maldives has little military muscle. ‘A standing army?’ UN Ambassador Manikfu responded quizzically when queried about the strength of his country’s defence forces. ‘We don’t even have a sitting army.’ The National Security Service is estimated to be only 4,000 strong, armed mostly with old British-made rifles and submachine guns. The Maldives was a protectorate of Britain until granted independence in 1965. It was almost miraculous, marveled some observers, for a handful of Maldivian soldiers to have held off for so long a group of experienced fighters armed with sophisticated weapons. The country has, in fact, seen several other unsuccessful coup attempts. The most serious coup was in 1980, two years after Gayoom took over from first president Amir Ibrahim Nasir. Nine former British Special Air Services commandos were stopped at Colombo’s airport after authorities were tipped off that they were on their way to topple Gayoom. Nasir’s brother, Ahmed Naseem, allegedly recruited the mercenaries. Luthfi himself was accused of planning to assassinate then-president Nasir in 1976. Gayoom freed him in 1979. Nasir was mentioned in connection with the latest plot, but the former president vehemently denied the charges from Singapore, his home since he left office. Maldivian officials said they had no evidence he was involved. In the Maldives itself, everything was fast returning to normal. While Indian troops were conducting a house-to-house search and scouring the outlying islands to flush out the plotters left behind, President Gayoom said his inauguration would go on as scheduled on Nov.11. The president, in power since 1978, is popular. Annual growth has been sustained at around 9%. Tourism is a major factor in that surge, but Gayoom has made sure the industry does not alter the country’s Islamic heritage. Tourists are limited to a number of island resorts where no Maldivians are allowed to be permanent residents. Some things may change, though. ‘After our nightmarish experience last week,’ said Manikfu, ‘my government is likely to reassess its future national strategy for our own self-preservation.’ In other words, more soldiers and modern weapons might well become a part of paradise. ***** Terror Stalks the Land [Manik de Silva; Far Eastern Economic Review, November 24, 1988, pp. 38-39.] As Sri Lanka writhed in the grip of mounting political violence just weeks before the 19 December presidential election, a series of crippling strikes in the public utilities was launched to back a demand that outgoing President Junius Jayewardene also dissolve parliament, whose term only ends next August. The demand was backed by the main opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), which says it will boycott parliament until dissolution is announced. The demand has divided the government, with Jayewardene apparently in favour of dissolution and Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, the ruling United National Party’s (UNP) presidential candidate, against. The indications are that Premadasa’s view will prevail. But both have indicated that they will dissolve parliament if the underground Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) will participate in a national caretaker government which will run the presidential and parliamentary elections. The JVP has refused. The opposition argues that the UNP-dominated parliament, and the resulting authority the sitting MPs enjoy, gives an unfair advantage to the ruling party at next month’s presidential race. More important, they claim parliament lacks popular support and legitimacy – a view shared by the Buddhist and Roman Catholic hierarchy. The present parliament was elected in 1977 but when its term was due to expire in 1983, the government successfully called a national referendum to extend its life for another six years. Thus, by the expedient of a simple majority in the referendum, the UNP managed to maintain its overwhelming majority in parliament. The government argues that it should not budge because of the violence in the Sinhalese-majority areas where the JVP is active. The killings and terror campaigns have been aimed at the UNP and the United Socialist Alliance (USA), a grouping of old Left parties and a breakaway section of former prime minister Sirima Bandaranaike’s SLFP. The UNP and USA have been left shaken and terrified. More than 500 UNP members have been killed in the past few months, including the party’s chairman, its general secretary, a cabinet minister, MPs and provincial councilors. The USA lost its leader, popular filmstar Vijaya Kumaranatunge, who was married to Bandaranaike’s younger daughter, and many ranking members and supporters. The JVP has denied responsibility for the violence but the killings are generally attributed to the Deshapremi Janatha Viyaparaya (Patriotic People’s Front or DJV), which is widely considered to be the JVP’s military wing. JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera, who is underground, is unambiguous in his admiration for the DJV. He denied to a newspaper that the DJV was instrument of his party but admitted that some of his members belonged to the DJV. He described DJV members as ‘patriots’ and said: ‘We will help them and support them. We respect them.’ Whoever is behind the violence has demonstrated a frightening capacity to disrupt public life. Anonymous demands that shops and businesses close and services be halted were backed by selective killings and attacks. Buses, trains and works at the port, in banking and the fuel-distribution service were effectively halted. Work on many state and privately owned plantations stopped and the government’s post and telecommunications services were disrupted. Hotel employees were told to stop work, forcing the government to send thousands of foreign tourists home. Emergency laws that named essential services had little effect at first though some people have since been persuaded to return to work. The government moved swiftly to deal with the strikes. An emergency regulation permitting the police and security forces to dispose of dead bodies without inquests has been invoked and curfew breakers and illegal demonstrators can be shot on sight. At least 80 demonstrators were shot dead in the first few days. The government has said it would apply the death sentence to anyone threatening any citizen with death or bodily harm or printing, duplicating or distributing threatening letters or leaflets. The same goes for anyone ‘organising or joining illegal processions or holding illegal meetings, illegally keeping away from work, or forcing others to keep away from work may be similarly punished,’ it said in a statement. It was reported that senior army officers would be appointed as High Court judges to quickly dispose of trials under these emergency laws. Despite the gravity of the situation, Premadasa has studiously avoided taking a tough line against the JVP. He has said before that there is no proof that the JVP is behind the violence and is carrying on campaigning amid the continued killings and disruptions. ‘Shops being closed give their employees a chance to concentrate on what I am saying,’ he said. Shortly after he handed in his nomination, Premadasa issued a statement saying that the ‘fires of the mind’ and the ‘fires of hunger’ must be doused not with ‘firewater but with cold water’. Analysts in Colombo have interpreted this to mean that he does not favour a harsh response to what is widely perceived as JVP-inspired violence. He has subsequently said at election meetings that though the policies of the JVP and UNP may differ, they both want to alleviate poverty and hunger. Premadasa’s efforts to try to bring the JVP into the political mainstream gathered added significance by a short reply by Wijeweera when a newspaper asked him what he thought of Premadasa’s refusal to speak out against the JVP. ‘Whoever they be, we judge people by what they do and not by what they say,’ was Wijeweera’s terse reply. The presidential race is essentially between Premadasa and Bandaranaike, though a third candidate is Ossie Abeygoonesekera of the Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya, a constituent of the USA. Abeygoonesekera claims the voter is disillusioned with both the UNP and SLFP and must have a third choice. The eight-party alliance which the SLFP said backed Bandaranaike’s candidature appears to be falling apart. The JVP has distanced itself – Wijeweera said Bandaranaike was in a weak position and the JVP did not need to cling to her to come into power. The Eksath Lanka Jathika Peramuna, formed by former members of the UNP, has also dropped out. The SLFP is, however, also steering clear of antagonizing the JVP. It has claimed the UNP used the JVP name and disrupted SLFP meetings but it has become clear that the UNP had no hand in these incidents. Some SLFP organizers who have been threatened have left their constituencies and Bandaranaike has requested and been granted police and military security. Jayewardene has ordered that it should be as tight as his own security. Bandaranaike has said that in the conspiracy to disrupt her campaign, the plan is to first display anti-SLFP posters using the JVP name and follow-up by assassinating SLFP members and attacking businesses owned by SLFP supporters. According to the Island, a newspaper published by a group of which her brother is chairman, a ‘powerful politician’ she has named is involved in the alleged conspiracy. Increasingly large numbers of moderates, professionals, businessmen and others of the middle class are deeply distressed by the anarchy and believe that the SLFP and the UNP, the country’s two established democratic parties, must come together to form a national government. Their thinking was reflected in a recent editorial in the Island which said: ‘A national government alone can obtain for the people a temporary respite. Everything else, including the presidential election, will come to look increasingly irrelevant in the face of the urgency for restoring normal conditions…’ *****

A Nation on the Brink [Anonymous; Asiaweek, November 25, 1988, pp.22, 27-28.] It was a sad irony. The violent strikes that paralysed Sri Lanka last week originated in moves intended to bring peace to the troubled island nation. When opposition leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike met President Junius Jayewardene on Nov.6 to set the stage for next month’s presidential elections, she spoke for seven parties as well as her own Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). Bandaranaike, herself a presidential hopeful, set ten ‘preconditions for peace’. Among them: the release of political prisoners, the repeal of Emergency Regulations and an end to all military operations, including those of the Indian peacekeeping force. However, the cardinal prerequisite, insisted Bandaranaike, was the immediate dissolution of Parliament. That, above all else, was the cause that had rallied the uneasy bedfellows of the opposition behind the SLFP. Since the drafting of the demands, two of the eight groups had pulled out of the alliance: the Eksath Lanka Janatha Pakshaya (United Lanka People’s Party), and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front), or JVP, the militant Sinhalese nationalist organization that has turned unremitting violence into a principal factor in Sri Lankan politics. Although out of the alliance, the JVP continued to support the opposition’s proposals. To the surprise of many, not least Prime Minister and presidential candidate Ranasinghe Premadasa, Jayewardene agreed to dissolve Parliament and to appoint an interim cabinet and an independent election committee. Bandaranaike, anticipating a return to power eleven years after being swept aside by Jayewardene’s United National Party (UNP), went home reassured. Back in the president’s residence, however, Premadasa protested, reminding Jayewardene that when he had been nominated as the UNP’s presidential candidate a month before, he had been assured that Parliament would not be dissolved. National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali sided with Premadasa but suggested that Jayewardene’s promise to Bandaranaike could still be honoured if the JVP would join the interim cabinet. Without such participation, he reasoned, peace was a forlorn hope. Scant minutes later, Bandaranaike received a telephone call from the president’s staff. Dissolution could only be considered, she was told, if JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera would accept membership in the interim cabinet. This Bandaranaike was no longer in any position to promise. That Sunday night, the capital brooded beneath a palpable apprehension. The next morning, the JVP called a general strike to protest the government’s ‘backtracking’ on the opposition proposals. First to respond was the 20,000-strong workforce of Colombo port, quickly followed by workers in the postal service, the Ceylon Electricity Board and the Petroleum Corp. By early afternoon, the port was closed and lines were forming outside the city’s few fuel stations that remained open. The government deployed troops to man essential services, but public anxiety had veered towards outright panic. With exhortations and death threats, the JVP and its ‘military wing’, the Deshapriya Janatha Viyaparaya, fanned the flames. Frightened crowds rushed to stock up food supplies, and scuffles broke out in markets. By Tuesday morning, kilometer-long queues at fuel stations were a common sight. The JVP began spreading its campaign of intimidation to its heartland in the island’s poverty-ridden south. Said of an official of the Ceylon Tourist Board: ‘[They] asked all hotel employees down south to participate in a placard campaign…there was no one to serve the tourists.’ Later that same day, the government officially advised tourists to revise their travel plans. The following morning, packed flights began ferrying holidaymakers out of Katunayake Airport. The disturbances sent tremors through both the government and the opposition. The SLFP was split into two, with one half urging Bandaranaike to re-open negotiations with Wijeweera and the other insisting that she join the government in recognizing the JVP as a common threat. Those who advocated negotiations with the JVP were party organizers from the south, who had good reason to fear for their lives. Ultimately, they prevailed. Jayewardene’s UNP, in turn, was divided on whether to accede to the opposition’s demands and dissolve Parliament. Acting Justice Minister Shelton Ranaraja argued for dissolution, saying that although ministers and MPs were protected by armed guards, their supporters were in dire jeopardy. But Premadasa’s camp held sway: there would be no dissolution until polling day itself, scheduled for Dec. 19. The following day, Thursday Nov.10, was nomination day. Amid escalating tension, candidates Premadasa, Bandaranaike and Oswin Abeygunasekara of the Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya (People’s Party) submitted their papers to the commissioner-general of elections. Trouble was expected, and the government had a day earlier clamped a 48-hour curfew in southern districts, declaring that demonstrators would be shot on sight. Undeterred, marchers gathered in the southern towns of Tissamaharama and Tangalla. Despite their orders, the army at first stayed its weapons. ‘We knew that if we opened fire,’ said a senior army officer, ‘we would give the JVP enough ammunition to last another couple of weeks.’ The deadly impasse was shattered when JVP cadres from within the crowd fired on the assembled military. Soldiers shot back. In all, fifteen demonstrators were killed. The government struck back with new emergency regulations, prescribing the death penalty for anyone issuing death threats, joining illegal processions, illegally staying away from work or forcing others to do so. The police were granted the right to dispose of dead bodies without postmortems, and military judges were empowered to hear cases involving subversion. ‘I believe the regulations are effective,’ Athulathmudali told Asiaweek at mid-week. ‘The JVP campaign seems to have lost some of its steam.’ But violence continued in outlying areas, where clashes between troops and JVP marchers claimed more lives. The anarchy in the south eclipsed continuing troubles in Sri Lanka’s predominantly Tamil north and east, but not for long. Even as Athulathmudali was voicing his cautious optimism on limiting the JVP’s disruptions, Tamil terrorists opened fire on a busload of people near eastern port Trincomalee, killing at least 24. The massacre was aimed at disrupting this week’s provincial elections. But in the south, the Jayewardene government seemed determined to stand eyeball-to-eyeball with the JVP and – at least until Dec.19 – not blink. ***** ‘A Fascist Force’ What is the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front)? President Junius Jayewardene says it is ‘a fascist force,’ and even the country’s ultra-left opposition agrees. ‘They are absolute neo-fascists,’ storms Dayan Jayatilleke, head of the Marxist organization Vikalpa Kandayama (Alternative Group), ‘bent on destroying the traditional Left just as Hitler and Mussolini did.’ But the JVP sees itself as purely Leninist, espousing a simplistic communist doctrine. ‘All enterprises will be nationalized without compensation,’ declares one cadre. ‘Econology will be given a prominent place and all land will be state land.’ The group is best known not for its ideology, however, but for its acts of violence. In recent months, the deaths of more than 500 leaders and supporters of the ruling United National Party have been attributed to the militant Sinhalese organization, as well as numerous incidents of arson and sabotage. Formed in 1965, the JVP found support among rural youths disenchanted by the inadequate economic policies of the Sirimavo Bandaranaike administration. Their strategy: attack police stations and other government installations. The government responded with a purge of JVP cadres in which, it’s now estimated, 20,000 people died. It jailed the group’s leaders. Sixteen years later, when Sri Lanka signed the peace accord with India in July 1987, the JVP reappeared and registered its disapproval by initiating the current campaign of intimidation and terror. Police intelligence officers believe its leadership is arranged around a core of eight. Reporting to this ‘politburo’ is a committee of 48 district leaders and representatives of student bodies. Despite this apparently well-ordered structure, JVP remains a shadowy organization. Its two known leaders – Rohana Wijeweera, 45, who was released in 1977, and Upatissa Gamanayake, 47 – are rarely seen or heard in public. The JVP’s enormous influence, say observers, is due to the other organizations – as many as 30 – that have gathered beneath its mantle. Most prominent among them is the Deshapriya Janatha Viyaparaya (Patriotic People’s Movement), said to be behind the killings attributed to the JVP. The DJV garners recruits through student bodies and militant Buddhist groups. In recent years the JVP’s appeal has broadened to include many members of the intelligentsia. The group’s ranks have swelled, reckons human rights lawyer Mahinda Rajapakse, because of outrage over the deaths and disappearances of civilians caught in the crossfire between the military and the JVP. Although openly condoning its actions, the JVP denies any connection with the DJV. This is reckoned to be simple political expedience. ‘By claiming to be non-violent,’ says an intelligence operative, ‘Wijeweera is trying to make sure he can come out into the open whenever he chooses without fear of prosecution. At that time, the DJV will simply disappear.’ ***** The Tamils Defy the Tigers [Sri Lanka Correspondent; Economist, November 26, 1988, pp.26 & 29.] The island is turning inside out. Just when Sri Lanka’s Tamil north-east may be reaching for peace, the Sinhalese south is hurrying towards martial law. The Tamils amazed most other Sri Lankans by turning out in force on November 19th to vote for a new provincial council for the north and east of the country. They rejected the boycott calls of the Tamil Tiger guerrillas, who during the five year civil war have been thought to be the most powerful Tamil group. Ordinary Tamils have now elected councilors who renounce separatism. They have, it seems, had enough of war. The election was the main plank of last year’s agreement between India’s prime minister, Mr Rajiv Gandhi, and Sri Lanka’s President Junius Jayewardene. Some powers, including control of the police and the collection of local taxes, are to be granted to the joint council. This is a fair dose of autonomy, but not independence. The Tigers kept forcing postponements, but the election had to be held before Sri Lanka’s presidential election, due on December 19th, The two main presidential candidates, Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike and the prime minister Mr Ranasinghe Premadasa, both dislike the deal with India. But Mr Jayewardene is determined to get a settlement in place and Mr Gandhi wants something to show for his efforts, in order to impress the Tamil electorate of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which is due to go to the polls in January. A cunning (if undemocratic) deal sewed up the Tiger heartland in the north. Advised by the Indians, the Tigers’ two main rivals, the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) and the Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front (ENDLF), agreed to contest the election. They then agreed to share the 36 seats, and thus do without a vote. In the east, the Tigers called a general strike. Locals were so frightened that 400 election officers had to be flown in from Colombo to man the polls. Still, the EPRLF, the ruling United National Party and the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress put up candidates, giving the Tamils, the Sinhalese and the Muslims – who each make up around a third of the population – their own people to vote for. In the main Tamil district of Batticaloa, 79% of the voters, risking reprisals, braved the Tigers and went to the polls. It was the biggest turnout ever in the district. Thousands were still queueing when the polls closed. Many said they were voting not for any particular party but for the chance of peace. They had already been given a taste of security by Indian troops, who have pushed back the Tigers in the east. The Indians had threatened to leave if there was a low turnout. The Muslims make up 8% of the country’s population, have similar grievances to the Tamils, but previously lacked political organization. This time they voted energetically: they have been galvanized by the leadership of 40 year-old Mr Mohammed Ashraff. His Sri Lanka Muslim Congress urged participation in the provincial council. The Sinhalese hardly bothered to vote. In the Sinhalese-dominated town of Amparai the turnout was only 5%. They probably felt abandoned by the government in Colombo, and are understandably bitter. The government has been urging Sinhalese to move into the area to balance the Tamil population. The EPRLF and the Muslims got 17 seats each in the east; the United National Party got only one. Altogether, the EPRLF-ENDLF alliance got three-quarters of the seats in the joint council. The Tigers’ refusal to take part looks like a mistake: for the first time, everybody is questioning their claim to be the Tamils’ only true representatives. While the north and east are demanding an end to violence, the rest of the country is fast getting bloodier. In contrast to the Tamils’ brave demonstration against Tiger threats, the country’s Sinhalese majority looks cowed in the face of the group of Sinhalese extremists known by its initials JVP, for Janatha Vimukti Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front). The JVP called strikes and demonstrations which brought the country to a halt two weeks ago. Many Sinhalese workers are still striking. They are probably staying away less out of support for than out of fear of the JVP: it has a habit of killing opponents. Some people fear that martial law will be declared. Others argue that a military government already exists. The president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces. A state of emergency has been in force since the last presidential election in 1982. Since November 2nd there has been curfew every night, all over the island. Troops may shoot curfew violators or demonstrators. Anybody staying away from work illegally can be sentenced to death. Soldiers are being called in to drive buses and petrol tankers and to man the power and pumping stations. They may even in judgment on cases concerning breaches of the new emergency regulations. Now that newsreaders on radio and television are being threatened, soldiers are being trained to take over from them. The sight of a uniformed presenter on the nightly news may bring home to Sri Lankans how close the civil war has brought them to army rule. ***** Assassination and Intimidation: JVP death squads lash out with wanton vengeance [Marguerite Johnson; Time, November 28, 1988, p. 13.] Death never seems to take a holiday in Sri Lanka. At one home in the town of Beliatta, where mourners met recently to pay respects to a victim of extremists, another gang of killers burst in. The terrorists killed eight of the mourners and beheaded the corpse. In the southern settlement of Hambantota, explosives were detonated at a grave site, blowing up a newly interred body. Presumably as a warning, the decapitated body of a reserve-police constable was placed on the front step of his house in Kamburupitiya. Violence seemed to be everywhere, with much of Sri Lanka paralyzed and many of its people caught in the middle. The latest terror campaign was launched by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Front, an extremist Sinhalese group that seeks to overthrow the government of President Junius R. Jayewardene. Early this week, JVP terrorists killed at least 45 people, most of them government employees who had defied a JVP order to stay away from work. As intended, the bloodshed by the JVP all but overshadowed the election for a provincial council in the predominantly Tamil eastern districts. That vote, the first in seven years, was a major step in efforts to gain a measure of local autonomy for the country’s Tamil minority. As soldiers and police conducted heavy patrols, a surprising number of Sri Lankans braved the intimidation to cast their votes – and for the moment at least, the violence appeared to recede. The Jayewardene government has responded to the JVP onslaught with draconian measures. Earlier this month security forces were given unprecedented powers, including the right to shoot anyone attending an illegal demonstration. The government also decreed the death penalty for people instigating protests or printing, writing and distributing threatening posters. Special military courts were set up to dispense speedy justice. In an interview with TIME, National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali admitted that the measures could lead to military repression, but explained, ‘We had to act. If we don’t do anything, the JVP will capture power.’ A shadowy group with Marxist origins, the JVP went underground after it was charged with having instigated the anti-Tamil riots of 1983, in which as many as 2,000 people were killed. In the 16 months since India and Sri Lanka signed a peace pact to end the bloody conflict between separatist Tamil guerrillas and the Sinhalese-dominated government, the JVP has resurfaced with a vengeance: JVP gunmen have assassinated more than 500 supporters of the accord, mainly members of Jayewardene’s ruling United National Party. Two weeks ago, in its most daring effort at destabilization yet, the JVP told government and other employees to stay away from work or be killed. Shops, banks, ports and post offices shut down. In some parts of the country, there were no buses, trains, electricity, water or telephone service. The JVP ruthlessly demonstrated its intent to make examples of those who defied its orders: five bus drivers who failed to heed JVP posters threatening death to those who reported for work were gunned down. Due to what it called ‘unsettled conditions,’ the government asked tourists to leave the island and canceled all package tours – a loss of revenue the country can ill afford. To counter the JVP’s threats to workers, authorities declared that employees in all essential services who did not report for work would be dismissed. To give the decree muscle, the government issued detention orders to hundreds of employees, which permitted them to claim that they were being forced to work. The ‘counter-fear campaign’ was necessary, said Athulathmudali, because many workers felt it was safer to disobey the government than the JVP. By that time almost 9,000 troops normally stationed in the predominantly Tamil Northeastern Province had been redeployed to the south, where the JVP is strongest. At least 250 JVP suspects were rounded up; in Colombo, police arrested an unknown number of so-called inside inciters in different sectors of the government, who were said to have coerced colleagues into staying out. Political opponents of Jayewardene expressed concern that tactics such as shooting at demonstrators might backfire, thereby garnering sympathy for the JVP. In recent months the JVP has sought to exploit disaffection with the 70,000 Indian peacekeeping forces stationed in the North and East, not to mention a desire for political change. Jayewardene has held power for eleven years. But since he will step down after Sri Lankans choose a new President in national elections Dec.19, former political allies of the JVP suspect that the group’s real goal is to create so violent a climate that the elections will have to be postponed. While most Sri Lankans think the JVP is the only force that could break Jayewardene’s iron hold on power, they do not view it as an alternative. Privately, some politicians compare the JVP’s elusive leader, Rohana Wijeweera, to Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge head widely held responsible for the deaths of more than 1 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979. Even in its stronghold in the south, the savagery of the JVP has generated more fear than support. Opposition leaders, the Buddhist clergy, the press, the Indian government and even voices within the security forces are suggesting that the only way to stop the JVP and save the country from anarchy lies in the formation of a national coalition government. With a powerful segment inside his party opposed to such a move, Jayewardene, for the time being at least, seems to prefer a military solution. [Reported by Anita Pratap/Colombo] *****

| ||