Ilankai Tamil Sangam13th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archive by Date Archive by Date Archive by Category Archive by Category About the Sangam About the Sangam Engage Congress Engage Congress Multimedia Multimedia Links Links Search This Site Search This SiteEditor Not logged in yet Log in (4 unreviewed) |

Kalivanar N.S. Krishnan, Tamil Comedian and Political ActivistA birth centenary tributeby Sachi Sri Kantha, November 25, 2008

It is rather unfortunate that scholarship on Tamil comedy in the performing arts (in stage, cinema, radio and TV) has been shoddy at best. Available information on Nagarkoyil Sudalaimuthu (N.S.) Krishnan (1908-1957), the king of Tamil comedy, in the internet has been insipid and banal. As such, I venture in this essay to view N.S. Krishnan (hereafter NSK) from a fresh angle, on his birth centenary falling on November 29, 2008.

In Tamil pulp literature, NSK has been compared with Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977). That both Chaplin and NSK had (1) a similar deprived upbringing, (2) early entrance onto the music-hall stage performances in London and southern Tamil Nadu as primary school dropouts, and (3) entry into movies from stage comedy in their mid-20s, precipitated this analogy of NSK as a Chaplin clone. The fact that NSK’s entry as a first-generation comedian into Tamil cinema [heralded by the release of Menaka on April 6, 1935] almost overlapped with Chaplin’s final performance as the tramp [in the Modern Times was in 1936] makes it inconvenient for easy comparison between the two comedians. In the 1930s, NSK’s fellow cinema comedians had prefix tag names like Buffoon Sanmugam, Loose Arumugam and Joker Ramudu. As of now, I could locate only two recorded references in English, relating to NSK’s career in comedy. These are as follows: Evaluation of Barnow and Krishnaswamy (1963)

I, for one, have difficulty in agreeing that NSK’s comedy is in the same plank as that of his illustrious contemporary Charlie Chaplin. It is like comparing a butterfly with that of a bee. Though there seems to be some superficial similarities between NSK and Chaplin, the differences (see below) outweigh the similarities. A thumb-sketch by Rajadhyaksha and Willemen (1999) The following synopsis on NSK’s stage and cinema career appears in the compilation of Rajadhyaksha and Willemen, that erroneously identifies the comedian’s birth year as 1905, instead of 1908.

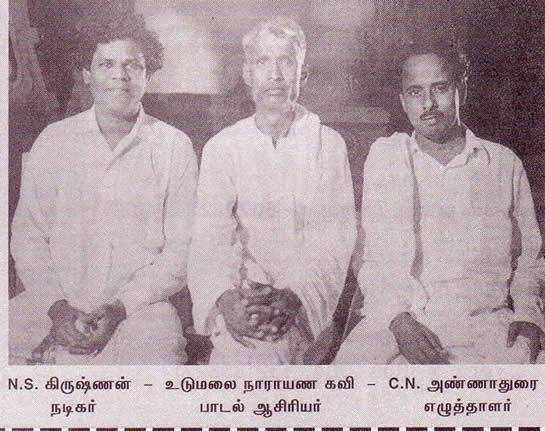

NSK’s other three prominent DMK associates in the Tamil movie world (noted above), namely lyricist Udumalai Narayana Kavi (1899-1981), script writer-politicians Anna (1909-1969), and Karunanidhi (b.1924) outlived him. Now, I provide comparisons between Chaplin and NSK brands of comedy.

NSK’s similarities with Chaplin (1) Both Chaplin and NSK had Dickensian childhood and drifted to stage performance because of it, for survival. What Chaplin’s biographer Theodore Huff noted, “a philosophy, teaching the sweetness of adversity, runs through all the amusing but penetrating studies of life Chaplin has given us.” may fit equally well to NSK. (2) The politics of Chaplin and NSK was left of Center, and both reveled in tweaking the noses of authority figures. While Chaplin’s most adventurous role of his career was parodying Hitler in The Great Dictator (1940), NSK never had an equally prominent role in his movie career, though he had a pungent song with suggestive pun ‘Theena Muuna Kaana’ propagating the glory of DMK in the movie Panam (lit. Money, 1952). NSK also visited the then USSR in 1951. (3) Both Chaplin and NSK had one of their wives in films, providing a companion foil. While Chaplin’s third wife Paulette Goddard (1910-1990) was a co-star with Chaplin in Modern Times(1936) and The Great Dictator(1940), it was unusual for an NSK movie without his second wife Mathuram accompanying her husband. It should be noted that before Paulette Goddard and before his first marriage, in late 1910s, Chaplin worked with his then flame Edna Purviance (1895-1958) in more than 30 films. (4) Both Chaplin and NSK had their entanglements with law enforcement. While Chaplin received warrants for his divorce trials and paternity suits but without spending a day behind the bars, NSK was arrested as an accused in a murder trial of gossip columnist/ muck-raker journalist C.N. Lakshimikanthan, and served jail sentence for nearly 2 years and 2 months (from Feb.12th 1945 to April 25th 1947). (5) Both Chaplin and NSK were creative in establishing their screen mascots. If the lovable tramp was Chaplin’s alter-ego for the silent screen, NSK’s creation for the talkie screen was the kattiyankaran character, adopted from traditional Tamil stage. The Tamil word ‘kattiyankaran’ has a wider range of meanings; literally a herald, but expanding into the boundaries of the function of buffoon, clown, jester and predictor. NSK’s differences from Chaplin (1) Primarily, the major difference of NSK’s comedy to that of Chaplin’s comedy was based on the distinction between silent and talkie movies. While most of Chaplin’s movies were of silent varieties, all of NSK’s movies were talkies. Only the last 5 (from 1940 to 1967) of nearly 81 movies of Chaplin were talkies. In his 1964 autobiography, Chaplin had noted: “Although a good silent film was more artistic, I had to admit that sound made characters more present. Occasionally I mused over the possibility of making a sound film, but the thought sickened me, for I realized I could never achieve the excellence of my silent pictures. It would mean giving up my tramp character entirely. Some people suggested that the tramp might talk. This was unthinkable, for the first word he ever uttered would transform him into another person. Besides, the matrix out of which he was born was as mute as the rags he wore.” If Chaplin’s speciality in comedy was visual, slapstick and pantomime, NSK’s comedy was mostly oral. Verbal humor filled with pun and repartee, as well as songs derived from stage folk plays constituted NSK’s ‘matrix’. This canvas limited NSK’s appeal to only Tamil-speaking audiences. There is disagreement on the number of NSK’s movies. Some web sources mention an inflated number of 150 movies. Vamanan (2004) had listed 82 movie titles as NSK’s output. When cross-checking with Film News Ananthan’s (2004) database on Tamil movies, I counted about 12 omissions. Thus, altogether, NSK’s movie productivity cumulates to 94 movie titles, nearly 50 lesser than the over-estimated number of 150. (2) Secondarily, while Chaplin had a long life of 88 years; with active involvement in movies from 1914 to 1967 when he released his final movie A Countess from Hong Kong at the age of 77, NSK had a short life span of 48 years, with a movie career limited to 22 years, of which two (between Feb 1945 and April 1947) were spent in imprisonment. During the pre-imprisonment phase of his career, 55 of NSK’s movies were released, among which three were his own productions. The period between April 1947 and his death on August 1957 saw the release of another 34 of his movies, among which NSK’s own productions accounted for four movies, namely Paithiakaran (1947), Nallathambi (1949), Manamagal (1951) and Panam (1952). Five more movies of NSK were released posthumously. Among these five movies, two each were MGR (Raja Thesingu, 1960; Arasilankumari, 1961) and Sivaji Ganesan (Ambikapathi, 1957; Thanga Pathumai, 1959) starrers. (3) While Chaplin had a good ear for music, had composed music for all his ‘sound films’ since City Lights (1931), and his voice was first heard in a six-line gibberish song [Se bella piu satore, je notre so catore – Je notre qui cavore, je la ku la qui la quai] he sang in Modern Times, music was hardly a major component of his comedy. In one of his early movies, The Vagabond (1916), Chaplin did play a street musician. NSK, on the other hand, was a folk-musician in his own right and used songs to spread his social reform message and enliven his comedy routine. Usually, he appeared with a percussion instrument in his characters. Singing comedians have been rare even in Hollywood. Among the 22 comedians/comedian pairs/comedian teams profiled by Lenoard Maltin for his 1978 book The Great Movie Comedians from Charlie Chaplin to Woody Allen, only Danny Kaye can be distinguished as a good singer. Among the Tamil comedians who followed NSK, only J.P. Chandrababu can be merited as a good singer. (4) While Chaplin was not known as a patron of folk arts, Venkatraman credits NSK as a rejuvenator and populariser of villu-p-pattu (bow song), a Tamil folk art form (story telling with satirical witty songs). NSK’s pioneering steps were boosted by a few of his movie proteges (actor S.S. Rajendran, comedian Kuladeivam Rajagopal, and one of his assistants Subbu Arumugam). (5) Healthwise, until he married his fourth wife Oona in 1944, by all contemporary accounts Chaplin suffered from a character flow of an over-sexed Don Juan, bedding nubile teenage starlets. An entry under the theme ‘Women’ in The Chaplin Encyclopedia notes that “On 11 January 1972, David Lewin of the Daily Mail quoted his response to the question, ‘What is your weakness?’, ‘My weakness?’ replied Chaplin, ‘Women. I love them all.’” Because his father died of alcoholism at the age of 37 and his step-mother Louise also was an alcoholic, Chaplin “had an understandable aversion to alcohol, which had brought such tragedy to his family”, noted his biographer Theodore Huff. Opposingly, NSK fell victim to alcoholism, though he had preached against this malady in one of his well known songs, and died of liver disease, aged 48, on Aug. 30, 1957. A Lesson Learnt in colonial Ceylon In the late 1970s, I read the memoirs of Tamil drama pioneer T.K. Shanmugam’s (TKS) ‘Enathu Nadaga Vaazhkai’ (My Life in Drama). In it, Shanmugam reminisced about an incident that had happened in colonial Ceylon. I then annotated this incident with the caption, ‘The Ceylon Tamil who demanded apology from Kalaivanar’ and this appeared in the Sudar Tamil magazine of May 1980. Unfortunately, neither I do have a copy of this print, nor is TKS’s memoir with me now. Thus from memory, I write the story as recollected by TKS. NSK has joined the TKS Brothers’ drama troupe Madurai Sri Bala Sanmuganantha Sabha at the age of 17. This probably would have been around 1925. Subsequently, this drama troupe was invited for a Ceylon tour, as was usual in those days. The sponsor of this Ceylon tour was one Shanmugam Pillai. While on stage, NSK had cracked an off-beat impromptu remark to his pal, “You play (kiss) with your love interest, while I kiss with my mother here.” This remark made Shanmugam Pillai, the sponsor, so furious that at the end of the play, he admonished the young NSK; “Merely to elicit a laugh from the audience, you never ever crack a joke that goes against our society's mores.” Flabbergasted NSK then tendered his apologies to Shanmugam Pillai. The fact that TKS had included this incident in his memoirs reveals his sincerity and the code of conduct adopted on the stage in those days. Lately, NSK’s comedy lines in movies have come to be appreciated for their cleanliness, uninfected by double entendre. It can be inferred that the admonishment of sponsor Shanmugam Pillai might have had some influence on NSK’s character. Coda In his autobiography, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi, was apt and has graciously compared NSK to Aristophanes (c 450-385 BC), a contemporary of Socrates (c 427-347 BC) and Plato (c 469-399 BC). Karunanidhi equated his political mentors Periyar E.V. Ramasamy to Socrates, and Annadurai to Plato. Though NSK was a benefactor to young Karunanidhi in the film world, this comparison of EVR, Anna and NSK is well fitting. To sum up, it can be noted that NSK’s song and comedy routines were so unique that though there has been quite a few tagged pretenders in the Tamil movie world, none could rival NSK’s stature. Some may scream that the situation, tempo and entertainment milieu have changed. But nothing prevents a comedy genius to take charge of a situation surrounding him to generate rib-tickling, thought-provoking comedy. This was true to the world of Aristophanes and to Chaplin and NSK as well. References Film News Anandan: Sadhanaigal Padaitha Thamizh Thiraipada Varalaru. Manivasagar Pathippagam, Madras, 2004. E. Barnow and S. Krishnaswamy: Indian Film. Columbia University Press, New York, 1963, pp. 173-174. C. Chaplin: My Autobiography. Penguin Books, 1964. T. Huff: Charlie Chaplin. Pyramid edition, 1964 (originally published 1951). Kalaignar Karunanidhi: Nenjukku Neethi (autobiography), part 1. Thirumagal Nilayam, Chennai, 1985. 2nd ed., pp. 141-158 and 314-322. L. Maltin: The Great Movie Comedians from Charlie Chaplin to Woody Allen. Crown Publishers, New York, 1978. G. Mitchell: The Chaplin Encyclopedia. B.T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1997. A. Rajadhyaksha and P. Willemen: Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Oxford University Press, new revised edition, 1999, p. 129. D. Robinson: Charlie Chaplin Comic Genius. Harry Abrams Inc., New York, 1996. Vamanan: Thirai Isai Alaigal. Part 1. Manivasagar Pathippagam, Chennai. 2004 (2nd ed), pp. 148-159. S. Venkatraman: Villu-P-Pattu. Indian Folklife Newsletter, April 2000; 1(1): 15 |

|||

|

||||