Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

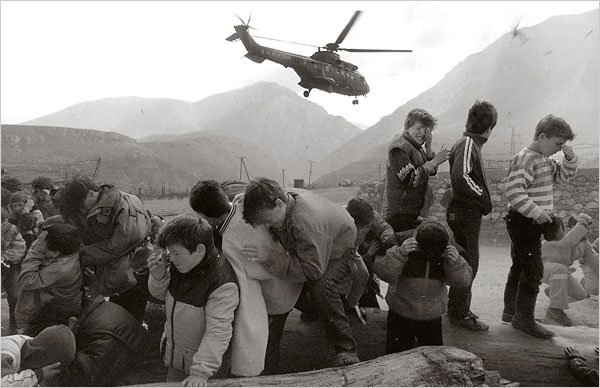

When to Interveneby Scott Malcomson, The New York Times, December 14, 2008

It is hard to date exactly when humanitarianism got decisively bound up with making war, although many would point toColin Powell's 2001 endorsement of relief workers in Afghanistan as a “force multiplier for us . . . an important part of our combat team.” In these two very different books, Conor Foley, an experienced relief worker, laments the transformation of humanitarianism into an aspect of politics, while Gareth Evans, a doughty Australian politician and head of the International Crisis Group, argues for something like its institutionalization. Both books are poised to influence debate as we make the turn into a post-Bush world.

As Foley notes in “The Thin Blue Line: How Humanitarianism Went to War,” human rights and humanitarianism became powerful movements in the 1980s and ’90s, and by now Amnesty International UK “has over a quarter of a million members, overtaking . . . the British Labor Party.” This shift from class politics to values politics occurred across the Western political spectrum, particularly in the prosperous ’90s. Nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, proliferated; governments integrated human-rights advocacy into their budgets and their diplomacy; the United Nations bureaucracy likewise seized the opportunity to promote human rights as central to the organization’s mission. Soon enough, a transnational “common culture,” in Foley’s phrase, of human rights and humanitarianism had taken hold among a surprisingly large number of people. And soon after that, as Foley shows, frustration set in. If humanitarian values were now universal (or universal enough), then why did they seem so threatened in the Balkans, Central Africa, the Caribbean and elsewhere? Foley says his fellow humanitarians looked to achieve their goals in two places: law and politics, not least armed politics. The legal route led in part through the United Nations, with its treaties and human-rights machinery, but the humanitarians’ most fervent investment was in the International Criminal Court, whose efforts got under way in 2003. It’s much too early to give up on the court, but Foley’s disappointment is pretty thorough. Anticipating that the court will change “from an instrument of justice to one of diplomacy,” he concludes: “The I.C.C. could become a useful mechanism for dealing with mid-level thugs and warlords, or retired dictators, where in-country prosecutions are considered too contentious. But it will not be the instrument of impartial, universal justice that its supporters claim. And for aid workers, this could make it as much of a problem as a solution in humanitarian crises.” Foley’s treatment of the court’s legal issues is informed and direct. He rightly draws attention to the coming debate on how the I.C.C. will define the crime of aggression, a question that was deferred by the drafters of the court’s treaty. This debate cuts very close to the privileges of powerful states, and Foley implies that for that reason, the identification of the crime of aggression will effectively be left to the great powers themselves. We shall see. His discussion of the humanitarians’ use of politics to further their ends benefits not only from his legal training but also from his insider’s experience. Foley seems to have been in almost every geopolitical mess from Kosovo to Afghanistan.He has watched as the nongovernmental organizations began, ever so slowly at first, to endorse the use of force for humanitarian purposes. And he has watched as “the integration of humanitarian assistance into military interventions” has led to “a steady increase in the number of attacks on aid workers over the last decade, partly because an increasing number of armed parties no longer respect the ‘humanitarian space’ within which aid workers operate.” One reason for that, of course, is that aid workers have often accepted the militarization of their work. Foley concludes: “The only international principles that potentially fit all the situations in which humanitarians work are those of independence, impartiality and neutrality by which the movement has traditionally defined itself. The shift away from these principles in recent years has caused more problems than it has solved.” In many ways, the crucial flaw in the legal and political avenues is that they both lead back to the United Nations Security Council, which, since its first session in 1946, has been captive to the veto power of its five permanent members: Britain, Russia, China, France and the United States. There have been many proposals for changing or evading this, some of them quite ingenious. But Gareth Evans is probably right to say that “any concession that … there are some circumstances that justify the Security Council being bypassed. . . seriously undermines the whole concept of a rules-based international order. That order depends upon the Security Council . . . being the only source of legal authority for nonconsensual military interventions.” Evans cuts a fascinating figure on the world stage. Always informed, sometimes alarming, never dull, he has a diplomat’s ability to listen and reflect, and a politician’s will to dominate a room. He is also an able and prolific writer. His achievements as foreign minister of Australia in the late 1980s and early ’90s were out of proportion to the influence of his country. And as the head of a nongovernmental organization, he took the International Crisis Group from being a modest advisory council to its current status as a global foreign-policy investigative, analytical and advocacy organization, with considerable influence on governments (which pay some of its budget) and the general public. His purpose in writing “The Responsibility to Protect: Ending Mass Atrocity Crimes Once and for All” is to advance the doctrine known by the Spielbergian acronym R2P, for which Evans, in his capacity as political entrepreneur, has been a crucial spokesman. Evans was extremely active on the international commissions that issued the reports in 2001 and 2004 that defined the doctrine of the responsibility to protect. And his reluctant acceptance of the centrality of the Security Council is of a piece with his general approach: that what matters in politics is the channeling of power toward humanitarian ends. He is seeking, with his advocacy of the responsibility to protect (and with this book), to institutionalize the idea that all states have an obligation to shield their own citizens from mass atrocities, and that if a state fails to do so, it falls to other states to take on that obligation. His encyclopedic knowledge of the international system enables him to make many specific proposals. Evans goes to heroic lengths, here and in the commission reports he helped write, to show that this doctrine is intended to be preventive first, meliorative second and invasive only as a last resort. In short, the international community should be oriented toward preventing atrocities before they get under way by helping the state in question, and only in extreme cases by using military force. The responsibility to protect is, in a sense, the reverse of its immediate doctrinal ancestor, the “right of humanitarian intervention,” which began its life as a direct challenge to state sovereignty. The R2P approach is to stress the duties of the sovereign state, rather than the power of the international community to trump that sovereignty. Evans readily acknowledges that the nature of the Security Council-based system means no R2P-based military action is ever likely to be taken against any of the permanent Council members. Unfortunately, it’s easy to see where this can lead. “If all this talk about responsibility to protect . . . is going to be used only to initiate some pathetic debate in the United Nations and elsewhere, then we believe this is wrong,” Sergey V. Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, told the Council on Foreign Relations not long ago. “So we exercised the human security maxim, we exercised the responsibility to protect.” He was referring to Russia’s protecting South Ossetia from Georgia. Neither author spends much time on Russia or China. But a values-based international system will not succeed without them. Foley and Evans both end their books with rather unexpected salvoes of anti-Bush feeling, which I take to be backhanded adieus to a man who, by enabling the international community to unite against Washington, has provided it with a coherence it might not otherwise have had. It will be fascinating to see what the community does when it no longer has George W. Bush to kick around — or to hold it together. Scott Malcomson, a former adviser to the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, is an editor at The Times Magazine. His most recent book is “One Drop of Blood: The American Misadventure of Race. |

|||||

|

||||||