Ilankai Tamil Sangam13th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archive by Date Archive by Date Archive by Category Archive by Category About the Sangam About the Sangam Engage Congress Engage Congress Multimedia Multimedia Links Links Search This Site Search This SiteEditor Not logged in yet Log in (no unreviewed) |

Anna’s Birth Centennial AnthologyPart 2: Panruti Ramachandran’s Essayby Panruti Ramachandran, February 22, 2009

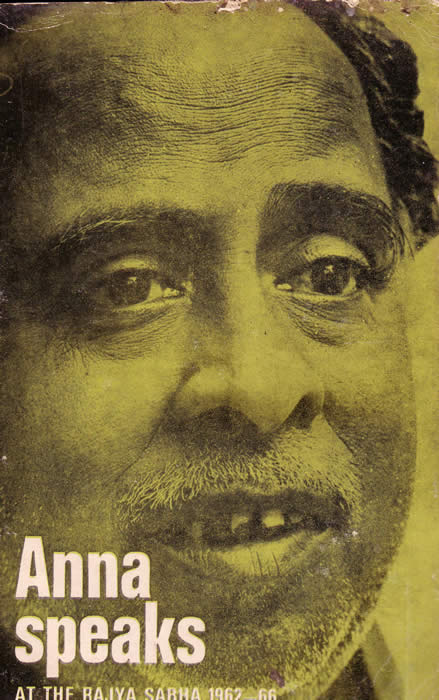

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha: I present below a fine essay (of 5,390 words) on Anna, contributed by Panruti S. Ramachandran, as a prelude to the book he edited in 1975, containing 13 of the speeches made by Anna at India’s Rajya Sabha, between 1962 and 1966. The essay covers many aspects of Anna’s versatile career, and has the advantage of being written by one of Anna’s younger lieutenants who knew him personally.

In quite a number of English books and academic journals, Anna’s creative career had been unjustly caricatured by the academics (both, Tamil and non-Tamil) and the Indo-Ceylon analysts of various political shades. Here is a representative sample, from Chidananda Das Gupta, an Indian movie analyst:

Factual errors [The birth year of Anna was wrong; and Kamaraj was not the chief minister of Madras state before the 1967 elections] aside, portraying Anna as a movie script writer-politician is akin to calling Charles Darwin (whose birth bicentenary was celebrated on Feb.12, 2009) a sailor cum ship handyman in the H.M.S.Beagle! A few academics (the types like K. Sivathamby and M.S.S. Pandian), in their popular avatar as movie critics - without any credible status in cinema skills! - also have unfairly critiqued Anna’s creative writings. In his essay on ‘The writerly life’, satirist R.K. Narayan (1906-2001) aptly mocked such academic snobs as follows [The words within parenthesis, are as in the original. The dots are inserted by me for brevity.]:

That Anna’s creative work has suffered in the hands of such academic snobs from the Occident is an understatement. Being semi-literate or illiterate in the varieties of the vast Tamil literature, such Occidental snobs have painted a half-baked caricature of Anna’s oeuvre. These caricatures deserve a separate study of their own.

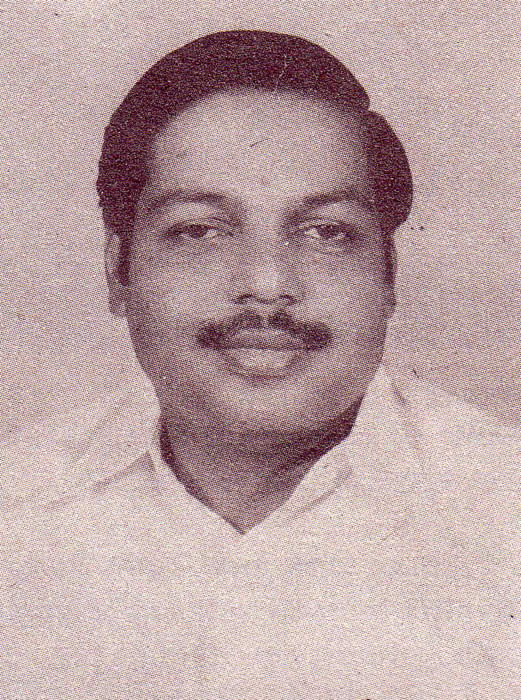

For the moment, the essay presented below by one of Anna’s lieutenants provides a counterpoint to the currently available error-prone portrayals of Anna’s creativity. In this essay, Panruti Ramachandran mentions how he came into Anna’s orbit in 1956, when he was the secretary of the DMK association at the Annamalai University. Born in 1937 at Puliyur, South Arcot district, Ramachandran received an engineering B.E. (Hons.) degree from Annamalai University. In 1966, he resigned the job he held at the State Electricity Board to become an active politician. In 1967, he was elected from the Panruti constituency on the DMK ticket. Subsequently, he was the Minister for State Transport for 5 years starting in 1971 in the Karunanidhi cabinet. Then, he fell out with Karunanidhi and joined MGR’s AIADMK party and served as the minister for electricity in MGR’s cabinet. Being fluent in English, he was a confidant of MGR and was actively involved as MGR’s right hand in the Eelam Tamils issue. Following MGR’s death and with the ascent of Jeyalalitha’s star, Panruti Ramachandran lost his clout, and hopped to the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) of S. Ramadoss. He deserted that party and currently serves as the presidium chairman of the Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam (DMDK) established by actor Vijaykanth in 2005. In the May 2006 Tamil Nadu state assembly elections, Ramachandran came third in the Panruti constituency that had returned him previously six times, since 1967. *****

Anna [courtesy: Anna Speaks at the Rajya Sabha 1962-66, Orient Longman, Bombay, 1975, pp. xv-xxvii] It was on 3rd February 1969 that the entire population of Tamilnadu literally crowded into Madras city. It was on that day that the news of the demise of our revered leader Anna reached the nook and corner of Tamilnadu, and came as a shock to each and every individual. From that moment, people began pouring into Madras city to have the last glimpse of their dear departed leader. They had come from the distant towns and villages, perched on the roofs of over-crowded trains and rickety buses and on foot. In one of the worst tragedies of the time, at least 28 persons were crushed to death and over 70 persons were injured due to their journey on the roof-top, when the Madras-bound Janata Express was passing across the Coleroon Bridge between the Coleroon and Chidambaram stations. No vehicles were permitted to go anywhere except to Madras city on that particular day, whether they were trains, buses, lorries, motor cars, taxis, tractors or any other form of conveyance. The grief struck almost every household not only in Tamilnadu, but also wherever the Tamils lived in other states and other countries. Such was the universal sorrow felt by the Tamils all over the world on the loss of Anna, who loved them above all else. Framed by the lofty columns of Rajaji Hall, he was laid in state amidst the weeping and wailing of millions. In their single-minded determination to pay homage they were not deterred by a wait under the blistering sun, or by hunger and foot-sore weariness. The sobbing people outside Rajaji Hall were such that even the entire police force mustered to control them could not do so, and had reluctantly to burst tear-gas shells several times. As the funeral procession went along Mount Road, now known as Anna Salai, a huge multitude of people witnessed it from the terraces, balconies, and precariously perched themselves on the sun-shades of the long line of buildings on both sides. The military van carrying the body looked like a floating ferry on the surging waves of the masses. So also, when it reached the Marina, it was once again afloat on the vast expanse of a sea of heads. Many were atop trees and most others filled the entire Marina Beach and a few other resourceful people climbed aboard the grounded ship Stamatis. The size of the crowd was beyond estimate. Some estimated it to have been over five million. The Guinness Book of Records has it that ‘the funeral of Anna was attended by the largest number of people in the world.’ This century has witnessed only three funerals comparable to anything like that of Anna’s. The first one was that of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak at Bombay in 1920, the second was that of Mahatma Gandhi in Delhi in 1948 and the third was that of Jawaharlal Nehru in Delhi in 1964. The city of Madras or South India has never in its history witnessed a funeral as poignant as Anna’s. Another striking feature of the entire funeral procession was the predominance of ordinary people like sweepers, scavengers, slum dwellers and hut dwellers. In fact when they tried again and again to break through the cordons to see the motorcade carrying the body of Anna and were prevented by the police – lest they should be run over by the passing vehicles – one woman braved the police and cried, ‘Anna is gone and I don’t mind being run over’. The women kept running for some time but she could not stay in the race for long. Such was the deep sentimental attachment the downtrodden had for their dear Anna who lived to make their life a little more worth living. Even today the abiding emotion the people of Tamilnadu have for him can be seen from the never ending stream of visitors to the Anna Memorial Square, artistically conceived and maginificently erected on the silvery sands of Marina Beach in Madras City. There is a saying in Tamil that one’s worth is known only after one’s death. If that is the index of one’s worthiness, Anna is the worthiest of all. In fact, an English daily while reporting the death of Anna carried the caption ‘A stormy political career ends.’ Really Anna was a wild storm that swept before it the distress of the depressed. The common man felt that someone near and dear to him had disappeared from the scene and it is doubtful whether at any time in its history, Madras has witnessed such a stirring and soulful scene. I first met Anna in 1956 when I was Secretary of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam student’s association at Annamalai University, near Chidambaram. The temple at Chidambaram is not merely a monument to the glory of Dravidian architecture, in legend and history; it is also symbolic of the finest hour of the Dravidian people. It was here according to legend that the story of the heights to which a man could rise by perseverance, devotion and dedication was written. It was here, even in a hierarchical caste-ridden society, that the lowest in the land, Nandanar, was supposed to have met and mingled with Nataraja, the God himself. With such traditions, it was therefore not surprising that my alma mater, the Annamalai University, became the intellectual fountain head of progressive political parties including the DMK party. Needless to say, Anna made a lasting impression on the politically conscious elite at the university of whom some became subsequently outstanding leaders of the DMK party. I consider it to have been my good fortune to have met Anna so early in my life and to have come under his magnetic influence. After graduating in Engineering, I worked for a time in the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board, but throughout the period I remained a faithful soldier of the party under Anna’s leadership. On occasions, when in my impatience I longed to resign from Government service and take up full time party work, Anna in his inimitable way would counsel patience. He might have probably felt that the DMK party, when it came to power would require technocrats, schooled in the skills and strategies of administration and his party men should by sufficient training equip themselves for this purpose. Anna’s generosity enabled me to contest the elections to the then Madras Legislative Assembly in the 1967 general elections. After being elected to the legislature, I was nominated as the Chairman of the Estimates Committee in 1967, an honour rarely conferred on a Member of the Assembly at the age of 30. My association with Anna during the two years he was the chief minister became closer. February 3, 1969 was a day of unbearable sorrow for me. I suffered an irreparable personal loss. Conjeevaram Natarajan Annadurai was born on the 15th day of September 1909 at the handloom town of Kanchipuram. The only son of middle-class parents, he spent an uneventful childhood. He caused his parents a great deal of anxiety by failing more than once before passing his school final examination. He had secured a backward scholarship at Pachaiyappa’s College, Madras. He exhibited the spirit of a true Anna by withdrawing from the B.A. (Hons.) degree examination after taking two papers, the reason being that his friend and colleague who was dear to him fell sick and could not take the examination and he genuinely felt that his action would give comfort and solace to his friend. Taking his honours examination in the year 1935, Anna stood first in the university. He won innumerable trophies in debates and oratorical contests and was elected secretary to the College Union and chairman of the Economics Association. Even as a student leader he was keenly sensitive to the political and social injustice around him. At college, he was attracted by the programme and policies of the Justice Party, a party that stood for justice for the large majority of non-Brahmins and for their liberation from Brahmin domination in the services and elsewhere. After a short spell as a teacher in a middle school at Peddunaickenpet, he became sub-editor of Justice, the English daily of the Justice Party. Periyar Thiru E.V. Ramasawamy, the great rationalist reformer and the founder of the Self-Respect Movement, was the first to recognize the potentiality of this talented young sub-editor. Anna was also attracted towards Periyar’s idealistic zeal in eradicating the social iniquities and inequalities. This led to his becoming an ardent and sincere follower of Periyar in his Self-Respect Movement. The Justice Party that had become the abode of the favoured few and the privileged classes of society, was converted into a mass movement by Anna under the leadership of Periyar and renamed Dravidar Kazhagam at the Salem Conference in the year 1944. This very resolution which brought the party ‘from palace to platform’ (as Anna later claimed) was known as the ‘Annadurai Resolution’. During his career as a social reformer he had edited some Tamil dailies – Navayugam, Kudiyarasu and Viduthalai. In the year 1942 he started a weekly journal called the Dravida Nadu to expound the principles and philosophies of the Dravidian Movement. Dravida Nadu caught the imagination of the masses like wild-fire and became the most popular weekly of its time. Owing to his differences with Periyar, Anna parted company with the Dravidar Kazhagam and formed a new party known as the Dravidar Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) on 17th September 1949, on the birthday of his political guru Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy. Probably in recent history this was the first organized South Indian political movement to fight against injustice meted out to South Indians. The main goal of the party was to establish a new society based on the three cardinal principles of democracy, rationalism and socialism. In order to achieve this goal, the party felt it necessary to resist northern domination and to work for the formation of a separate independent sovereign Federation of Dravidian Socialistic Republics, comprising the present four southern states of India – Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka. Anna worked hard to mobilize support and sympathy for his philosophy from the masses. During the first seven years of the DMK’s history, it did not want to contest the General Elections or capture political power. It was at the historical Tiruchirapalli Conference in 1956 that the DMK took an opinion poll and decided to contest the general elections in 1957. Anna said, ‘We realized that we must either be politically capacitated or be ruined by democracy’, as he launched his youthful party into the election fray. The DMK, won 15 seats in the Assembly and Anna entered the state legislature as the leader of this small but eloquent and effective opposition. In 1959, in the Civic Elections of Madras, the DMK captured the majority of seats and, on 24th April 1959, the first DMK mayor was sworn into office. In the 1962 general elections, though Anna was defeated in his home town Kanchipuram, his party won 50 seats in the Assembly. Anna was elected to the Rajya Sabha and went to Delhi, where he distinguished himself as a brilliant orator and authentic spokesman of Dravida Nadu. It was in the year 1962 that the entire country was shocked by the invasion of the Chinese across the Himalayan borders. The shock was more intense and severe to Anna because it was the first time that Anna was led to review his own goal of achieving an independent Dravida Nadu. In fact at that time he was serving his sentence in Vellore jail for his part in agitating against the rising prices. Without any hesitation whatsoever he came out with a bold statement advising his followers: ‘In our anger against the Congress regime, we should not commit the mistake of slackening our efforts against the foreign invader. We of the DMK consider it our sacred duty to rush to the help of the Indian government in its efforts to protect and safeguard the sovereignty of our soil.’ Anna felt that in times of external danger like the Chinese invasion, Indians should march as one people. Subsequent to this, the Government of India came with a constitutional amendment bill which debarred any secessionist party from contesting the general elections. Anna was not prepared to commit political hara-kiri by clinging to a demand that the changed circumstances of the country did not justify. He gradually realized that he could still win his battle within the framework of the Indian Union. Accordingly the constitution of the DMK party was amended in such a way as to work for a closer Dravidian Union of the four linguistic states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka within the framework of the Indian Constitution by obtaining more powers for the states to the extent possible. The year 1967 was a water-shed in the history of Tamil Nadu. It was at that time that the fourth general elections were held. The grand strategist and shrewd tactician that he was, Anna realized the defective electoral system prevailing in a country like India, where a party could be elected to power even with minority votes while the majority votes were shared by a number of opposition political parties. He worked out an understanding among all the opposition political parties in Tamil Nadu, covering both the extreme rightists like the Swatantra and the extreme leftists like the Marxist Party. He gave a slogan to all the opposition parties: ‘United we stand, divided we fall.’ This worked wonders even beyond Anna’s expectations. The results of the general election came as a surprise to many and a shock to a few. It was a landslide victory and a clean walkover for Anna’s party. The Congress Party in Tamil Nadu had collapsed like a house of cards. The DMK won all the 25 seats it had contested for the Lok Sabha and 138 of the 173 seats in the state assembly. The Congress got a meager three Lok Sabha seats and fifty assembly seats, though they had contested all the available seats. The President of the All India Congress Party was defeated by a 28 year-old DMK student in his home town. All except one of the members of the Tamil Nadu cabinet, including the Chief Minister, were defeated. One Union cabinet minister and two union deputy ministers were also defeated. This was the first time in the history of India that the people of a state voted an opposition party into power with such a thumping majority. On 6th March 1967, the DMK government was sworn in, with Anna as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu. In Anna’s cabinet, the youngest was only 32 years old. The rest, except for Anna himself who was 58, were below 48 years of age. The party presented a picture of youthful vitality. The members of his ministry traveled in small cars and drew a salary of Rs. 500/- a month. As chief minister, Anna himself set an example by continuing to live at his unpretentious residence at Avenue Road, Nungambakkam. Taxes on dry lands were abolished. Rice was sold at one rupee a measure in the cities of Madras, Coimbatore and suburban areas. Pre-university education was made free for the children of those parents whose annual income did not exceed Rs. 1,500/- Anna went abroad to the United States and Japan during this period. He was awarded the honour of sub-fellowship at the Yale University in the United States. In the year 1968, the Annamalai University at its convocation held at Chidambaram conferred on him a doctorate. Anna’s administration succeeded in projecting the image of his government as truly representative of the man in the street. Though the period of his chief ministership was short, his achievements were many. As a rationalist, Anna got legislation passed legalizing simple marriages performed without priestly intervention, in keeping with the self-respect principles preached by the social revolutionary Periyar decades before him. The state under Anna’s leadership also was the first in India to foster and encourage intercaste marriages by awarding gold medals for every intercaste couple. A cause which was dear to his heart all through his life was his abundant and abiding love for Tamil. It was this cause which made him popular, and also sent him to jail both in the first and last instances of his political career. In his unrelenting resistance, he expressed the anger and the deep frustration of the people. It was their sentiments he echoed, when he proclaimed to the Rajya Sabha: ‘My language is two thousand years old. If you drink deep of the nectar of the Tamil classics, you will want only Tamil to be National Language.’ When he became the chief minister, he achieved his aim of elimination of the domination of Hindi from Tamilnadu by having a resolution passed in the state assembly, adopting the two-language formula; i.e., Tamil and English in Tamil nadu, in a special session convened for this purpose. As one who worked for the renaissance of the Tamils and believed that only by furthering the cause of the Tamils, would he be able to achieve a new society, it was a historic event for his homeland to be re-named ‘Tamilnadu’. At long last the land of the Tamils regained her proper name which she had lost after the second century BC. Anna himself spoke with pride of these three achievements of his regime as ‘historic’. The secret of his phenomenal hold over the masses deserves study. Some argue that it was his brilliant oratorical capacity. Of course a vital ingredient of Anna’s charisma was his eloquence. His consummate mastery of words had earned for him the endearing appellation, alliteration Annadurai even as a student at Pachaiyappa’s College. He attracted all college students by his oratory in both English and Tamil. He had the ability to stir and stimulate, while conveying his deep and genuine concern for the people. Though he could engage in adroit verbal gymnastics when occasion demanded, he spoke to his thambis in words simple and easily understood by the most illiterate. Speaking extempore, he could hold forth on almost any subject. In fact, he once made a brilliant speech on ‘no topic’ when the organizers of the meeting told him that there as no topic scheduled for the meeting. Anna was perhaps the first politician in India who raised money for his party by selling tickets for his public meetings. His party, in its days of struggle, was not supported either by the landlords or the industrialists and had to depend on the middle class and the common people. People flocked to listen to Anna and other DMK leaders and bought tickets for the meetings as they would do to see a movie. This was a unique experiment in Indian politics which Anna innovated. Anna’s style was perfectly tailored to his purpose. He spoke to the illiterate masses who needed time and elaborate explanations to digest complicated concepts. So he chose two or three salient features, and discussed them from various angles, reiterating each point with witty examples and logical arguments. It was this strategy which made him such an effective mass leader. Anna spoke equally well in Tamil and English. His hard-hitting maiden speech in the Rajya Sabha convinced the members of his mastery of English. Thereafter, whenever he stood up to speak, everyone sat up to listen. This unique craftsman of words spoke of the ‘bloodless revolution of the ballot boxes’ and denounced ‘men who hankered after the loaves and fishes of office.’ He used his irrepressible sense of humour to cut through tense situations and sooth frayed tempers. In the Tamilnadu assembly, an opposition member, Thiru K. Vinayakam enquired about the implementation of the water supply scheme at Tiruttani where the famous shrine of Lord Subrahmanya is situated. Anna remarked with a smile: ‘I am glad Vinayakam, the elder brother, takes such an interest in the temple of his younger brother Lord Subrahmanya.’ At an American press conference, when questioned about his policy on abortion, he came right back with ‘We abhor abortion.’ It is claimed by some others that the people showered affection on him for his outstanding contribution to the field of literature. It is true that Anna had his own distinct style both in the method of his writings and in the manner of choosing his themes. His style was a complete breakaway from the old difficult and artificial style into a new, simple but musical one. It can as well be said that he ushered in an era of ‘literacy revolution’ by which literature instead of limiting itself to intellectual circles reached out to large masses outside. His books of that time numbering about thirty, were all best sellers. His plays Velaikkari, Oor Iravu and Sorgavasal were compared to those of Bernard Shaw by critics like Kalki Krishnamurthi. It is gratifying to note that later on when they were made into films, they were most popular and successful. Apart from writing prose and poetry, short stories and novels, dramas and satires, he himself acted in several plays, such as Chandra Mohan, Chandrodayam and Needhi Dhevan Mayakkam, written and popularized by himself. The number of English and Tamil dailies and weeklies edited by him is eloquent testimony to his journalistic caliber and vigour. As an author and actor, playwright and poet, satirist and statesman, Anna combined in himself excellence in every field of literary activity. His entry into the field of Tamil literature ushered in an era when a new style was born, now emulated by so many others. There are still several others who think that Anna owed his popularity to his skilful conduct of political affairs. For the first time in the field of politics Ann abrought to bear the relationship of a closely knit family in running his political party. In the DMK the members formed themselves into a family of thambis led by Anna (their elder brother). The word ‘Anna’ means in Tamil ‘elder brother’. His leadership was supreme. His decision was final, not because he was a tyrant who compelled blind obedience as leader of the party, but because he was their beloved Anna who inspired devotion and evoked enthusiasm. Anna, as a loving elder brother, merely guided them. The extreme opposite of an arrogant political boss who ruthlessly stifles initiative and leadership among his followers, Anna believed in sharing responsibility and fostering talent. That is why the DMK has so many popular leaders and effective orators. They were encouraged to speak, to organize conferences and lead agitations. Anna took great pride in their achievements and graciously acknowledged their success in public. No wonder to his thambis his slightest wish was law. In all party disputes, an appeal from Anna brought his thambis back into line. This close-knit unity, inspired confidence in an electorate disgusted with the ugly factional in-fighting within the Congress Party. But for the courage and confidence Anna possessed it would not have been possible for him to attract such a large number of talented young men. The very fact that he formed a political party independent of any other national organization at that time when the feeling and fervour of nationalism was so high in India, was a clear demonstration of his courage and conviction. Every other political party in the country, including the Communist Party, was schooled in Congress traditions and its leaders had been followers of Mahatma Gandhi at one time or other. It was patriotic and fashionable to have been the camp followers of Gandhi and Nehru and echo the glories of a resurgent united India. To a leader of his eminence and ability the highest positions in the country would have been open had he taken the line of least resistance and walked on the popular side of the road. Anna and the DMK party were exceptions. At such a time, to speak of the identity of his own people, to fight for their rights, to stand against the domination of one part of the country by another and to point out the injustices meted out to his people, required phenomenal courage. Even before independence, Anna proved himself a patriot under very trying circumstances. At that time, he was an active disciplined member of the DK. Periyar was his only political guru. The fiery old rationalist declared that Independence Day was to be observed as a day of mourning. The young Anna courageously wrote an editorial in the Dravida Nadu pointing out that the DK had condemned foreign rule as early as 1939. ‘Even while the anti-Hindi agitation was at its height, we passed a resolution demanding complete independence. We have made it clear on many occasions that our opposition to the Congress must not be misconstrued as opposition to freedom.’ He called on all Dravidians to celebrate Independence Day as a day of deliverance. He was severely censured by Periyar for his ‘impertinence.’ Anna never in his entire career failed to challenge any injustice in public life. He presented a picture of an undaunted hero fighting a fire-breathing dragon. After all, what is courage? As Confucious said, ‘If you see what is right and don’t do it, you are a man without courage.’ Courage is nothing but fighting injustice, which Anna did. His compatriots attributed his fame to his sincerity of purpose, spirit of selfless service and sacrifice to his cause. It is very rare among politicians to follow up their words by deeds. But Anna was one to practice what he preached. Whether it happened to be a black-flag demonstration or burning a chapter in the Constitution or for that matter any agitation, and courting imprisonment, Anna as leader was in the forefront. As many as eight times he courted imprisonment for the cause in which he sincerely believed. His movement was always planned in advance, programmed in minute detail, implemented without violence, and it culminated in success. Though he was different in many respects from Mahatma Gandhi it was still a paradox that they had certain common characteristics of staging peaceful and non-violent agitations. He was not one of those who sent his volunteers to action, himself remaining aloof or underground. He considered his means as important as his ends. He always believed in openness of mind and in the free and frank exposition of his cause. ‘Growth with stability’ was his motto. Step by step was his method. This evoked the admiration and active support of the common folk who anxiously waited to carry out his command at any moment. Nothing is more precious than one’s own life. But for Anna it was different. When he fell ill in the second year of office as chief minister, he was suspected of being stricken with cancer. Immediately he was taken to the United States where Dr. Miller treated him. As Anna was very weak and failing in health, Dr. Miller advised him to take complete rest in an air-conditioned bungalow and to cut down travel to the minimum, and if this was unavoidable, he must do so in an air-conditioned car. But to Anna for whom simplicity was a way of life, that was really a threat to his very philosophy and way of life. He had to choose only one of the two alternatives: either to live for some more time or to die for his simplicity. Even before his landing in Tamil Nadu, the people were so anxious about his health that the Government of Tamil Nadu had decided to aircondition a bungalow and to provide him with a new imported airconditioned car. But to the shock of many, Anna chose not to live in an airconditioned bungalow and not to travel in a luxury car but preferred to stay in his unostentatious residence and to travel in a small indigenous car. Even when an offer was made to aircondition at least a room in his residence he rejected it forthright. Such was his tenacious attachment to the simple way of living even at the risk to his own life. To the last till his life deserted him, he did not desert simplicity. His humility was such that even his worst political adversaries had great regard for him. For all the talents he possessed he would have been excused if he had been arrogant. But he was never so. He was so humble in his approach that even after his massive victory in the 1967 general elections, he made it a point to secure the blessings of all his political opponents before assuming office. In particular, when he called on his political guru Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy at Tiruchirapalli after his dissociation with him for eighteen years, it was a pleasant surprise even to Periyar. The grand old patriarch was moved to tears when he embraced Anna after such a long time. As Periyar himself on a subsequent occasion stated, he was absolutely embarrassed to receive Anna especially after his vehement criticism of the latter over a long period of eighteen years. It is said that he who makes history has no private life. Anna who made history had no such life of his own. Anna had not even the slightest wish to amass wealth for himself. Had he desired to do so, he could have become the richest by his own writings and speeches. But his integrity was such that when he died, the only property he left behind was the love of his people. This prince among men, to whom the people would have given anything, died in debt and his widow had to be helped by his party out of financial difficulties. The yardstick for measuring greatness has differed from age to age and from country to country; but our people for ages have always placed character and integrity above all as a yardstick for measuring greatness. His character and integrity above all are responsible for Anna’s charisma. To fulfil the ambition of the dead is the responsibility of the living. To complete the task of the dead is the duty of the living. What were his ambitions and what were his tasks? His ambition was to form a new society based on the principles of democracy, rationalism and socialism for Dravidians in their own style and suited to their own genius. It was his firm faith that this was the only way to achieve the liberation of the common man from the evils of exploitation. It is well known that his concern for the common man was so great that he considered himself one among them. Writing to his thambis in Dravida Nadu he observed: ‘You and I are common men – me specially a common man, called upon to shoulder uncommon responsibilities.’ He believed that ‘democracy is not a form of government alone, it is an invitation to a new life, an experiment in the art of sharing responsibilities and benefits, an attempt to generate and coordinate the inherent energy in each individual for the common task.’ Hence, we cannot waste a single talent, or impoverish or allow a single man or woman to be stunted in growth or be held under tyranny. Rationalism was his religion. He hated the cant and hypocrisy, the blind superstition and corruption which had obscured the purity of religion. He stood against idol worship, the regimented rigours of organized religion, and karma and God’s will being quoted in season and out by vested interests to justify inaction against the bondage and poverty of his people. He believed in real faith, in faith which aspired to feed the hungry and comfort the suffering. ‘True faith in God is deep faith in human beings,’ as he himself said in one of his films, Sorgavasal. That true faith was his religion. His socialism was scientific. He never confined himself to the four walls of set doctrines and never-changing dogmas. He wished society to rid itself of exploitation of all kinds. In fact, Anna wrote: ‘Concentration of wealth in the hands of a few is like a deluge. That would destroy not only the weaker sections of society but even those possessing it.’ His entire economic philosophy was based on the socialistic approach of ensuring a good and decent living for one and all. This is the message left by our revered Anna to his thambis, this his gospel. *****

|

|||

|

||||