Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Fondly, Greenland Loosens Danish Ruleby Sarah Lyall, The New York Times, June 21, 2009

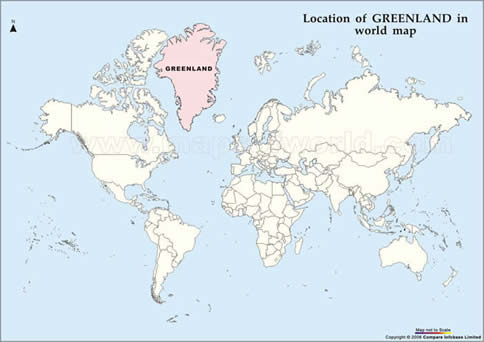

The thing about being from Greenland, said Susan Gudmundsdottir Johnsen, is that many outsiders seem to have no clue where it actually is. “They say, ‘Oh, my God, Greenland?’ It’s like they’ve never heard of it,” said Ms. Johnsen, 36, who was born in Iceland but has lived on this huge, largely frozen northern island for 25 years. “I have to explain: ‘Here you have a map. Here’s Europe. The big white thing is Greenland.’ ” But Greenland, with 58,000 people and only two traffic lights, both of them here in the capital, is now securing its place in the world. On Sunday, amid solemn ceremony and giddy celebration, it ushered in a new era of self-governance that sets the stage for eventual independence from Denmark, its ruler since 1721.

The move, which allows Greenland to gradually take responsibility over areas like criminal justice and oil exploration, follows a referendum last year in which 76 percent of voters said they wanted self-rule. Many of the changes are deeply symbolic. Kalaallisut, a traditional Inuit dialect, is now the country’s official language, and Greenlanders are now recognized under international law as a separate people from Danes. Thrillingly, the Greenlandic government now gets to call itself by its Inuit name, Naalakkersuisut — the first time in history, officials said, that the word has been used in a Danish government document. “It’s a new relationship based on equality,” said Greenland’s new, charismatic prime minister, Kuupik Kleist, speaking of the balance of power between Greenland and Denmark. He compared the situation to a marriage in which the wife was bossing around her henpecked husband. “From today,” he said, “the man in the house has as much say as the wife.” But this is a delicate time, full of hope and trepidation in equal measure. Few Greenlanders graduate from college. The country is rife with social problems like alcoholism, unemployment and domestic violence. Infrastructure improvements are punishingly expensive and desperately needed in a place where, for instance, people travel by boat or plane because there are no roads connecting towns. Meanwhile, global warming is rapidly melting the mighty icecap that covers some 80 percent of Greenland’s 840,000 square miles. Although that is destroying traditional hunting livelihoods, it also brings new opportunities for exploring and exploiting what could be vast reserves of oil and minerals deep beneath Greenland’s surface and in the waters around it. Under the new self-government agreement, Greenland will get half of any proceeds from oil or minerals. The other half will go to Denmark, to be deducted from the grant of 3.4 billion kroner, or $637 million, that it gives Greenland each year. The hope is that eventually the subsidy can cease altogether and Greenland will be ready for independence. The prospect of Greenland’s benefiting from what may be a lucrative oil and mineral business raises an obvious question: What’s in it for Denmark? “It’s not a question about money,” the Danish prime minister, Lars Lokke Rasmussen, said in an interview here. “This is a question of respecting Greenlandic people and giving them the right to decide their own destiny.” The right to self-determination, particularly for indigenous people like Greenland’s Inuit, more commonly known as Eskimos, was a recurring theme this weekend. Two exotically dressed visitors from Norway’s Sami Parliament, which represents the country’s reindeer herders, appeared at a trade exposition here on Saturday, marveling at how far the Greenlanders had come. “They’re many steps farther along than we are,” said Marianne Balto, Parliament’s vice president. “It gives hope to the Sami people.” Iceland’s president, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, was there, looking at it from the other side, recalling how his country ended hundreds of years of Danish rule with independence in 1944. Bent Liisberg, a lawyer from Norway, which was owned for hundreds of years by Denmark and then by Sweden, had much the same perspective. On Sunday, he was carrying a backpack from which protruded a little Greenlandic flag, its red-and-white design representing the sea, sky and sun. “This is a great day for small nations,” he said. Nuuk is a curious city, where old, brightly colored wooden houses built by the original Danish settlers coexist with rows of down-on-their-heels apartment buildings that are almost Soviet in their soullessness. Its harbor is impossibly quaint and its views breathtakingly beautiful; its center is indifferently maintained and virtually paralyzed by traffic at 8 o’clock every morning, when the workday begins. It has 15,000 residents, and many seemed to be out and about at 7:30 a.m., when the procession down to the harbor for the self-government celebrations began. It snowed the day before — giving a strange feeling at a time of year when there is virtually no darkness — but on Sunday the sun blazed across the water. Representatives from 17 countries and territories, including the United States and the Faroe Islands (also owned by Denmark), were there. Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, wearing a traditional Inuit costume with shorts made of seal fur and a short, beaded shawl, solemnly handed over the official self-government document to the chairman of Greenland’s Parliament. For Greenlanders, who can feel like second-class citizens in Denmark, the new arrangement bolsters a national pride they almost didn’t know they had. “It is nothing that we will feel on a day-to-day basis, but the symbolic value of this gives people so much more confidence,” said Peter Lovstrom, 28, who works at the national art museum in Nuuk. He said it was impossible to feel rancor toward Denmark, given all of the intermarriage and connections between the countries. “We all get along. We have to get along,” Mr. Lovstrom said. “But I feel a bit more Greenlandic now.” |

||

|

|||