Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

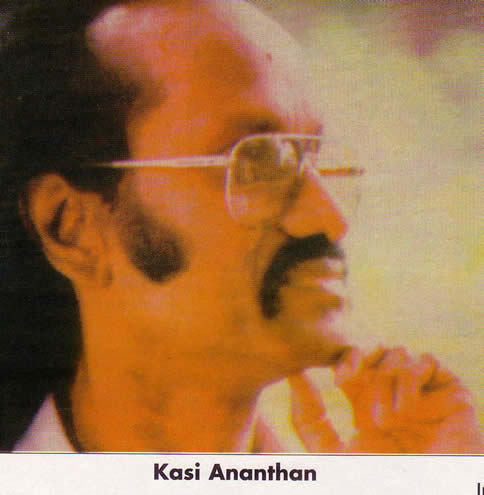

Kasi Ananthan at 70Poetry and powerby Sachi Sri Kantha, April 6, 2009

Have you heard the recent song sung by T.L. Maharajan, ‘Prabhakaran vazhi Nillu – Pahai piLLakkum puli veeran vazhi ninru vellu’ [ (Will you) stand by Prabhakaran’s path – An enemy splitting Tiger’s path to win.]? It was penned by Kasi Ananthan, the prime poet laureate of Tamil Eelam. The hard consonants (ka-sa-da-tha-pa-ra) of the lyrics swiftly roll in the tongue of singer Maharajan, eldest son of the great Tiruchi Loganathan (1924-1989), an acclaimed Tamil singer of the 1940s and 1950s cine world. The powerful lines of the lyrics are besotting. The voice that gives life to the song is mesmerizing; especially the diction of words like ‘Nillu’, which seems like a carbon copy of the sonorous voice of Tiruchi Loganathan. The combination of the lyrics of Kasi Ananthan and the voice of Maharajan is a sweet example of poetry and power – the subtitle of this essay. The song can be listened to in YouTube instantly, if you google ‘Kasi Ananthan and T.L. Maharajan.’ Kasi Ananthan’s 70th birthday passed on April 4th. He was born in 1939 to Kathamuthu and Alagamma, at Amirthakazhi, Batticaloa.

Tamilan Kanavu (The Dream of a Tamil) – 1st poetry collection After elementary and high school education in Batticaloa, Ananthan moved to Madras and graduated from Pachchiappa College, Chennai. He returned to Ceylon in 1968 and introduced himself as Kasi Ananthan to the Tamil literary world on the island. I was then a high school student at the Colombo Hindu College, Ratmalana, and occasionally listened to his talks at school during festive occasions. At that time, he was introduced as Unarchi Kavignar (Poet of Emotions). His early verses had shades of famed Tamil Nadu poet Bharathi Dasan (1891-1964), an ardent Tamil activist. Kasi Ananthan had dedicated his first poetry collection, Tamilan Kanavu to C.N. Annadurai. In 1978, I wrote a survey essay on the Tamilan Kanavu collection and Kasi Ananthan’s early poems in Tamil that appeared in six parts in the Sudar magazine, during 1979-80. As such, I refrain from repeating the details noted in that essay. My theme for this essay is on another of Kasi Ananthan’s short collection that appeared in 1975. Theru Pulavar Suvar Kavikal (A Street Poet’s Graffiti) This collection, called Theru Pulavar Suvar Kavikal, contained 28 short verses. Using wit as a weapon, Kasi Ananthan composed free verses. His canvas was the socialist regime of Madam Sirimavo Bandaranaike during 1970-77 that tortured him. It provided ample pegs for Kasi Ananthan to poke fun at Tamil society. Personally, he suffered detention, torture and repeated prison sentences. Thus, his poetic arrows were targeted at traitors, collaborators, unsavory social climbers, as well as the powerless masses who danced to the tunes of these social parasites. Free verse is described by Lillian Hornstein (1973) as, ‘a type of poetry in which the line is based on the natural cadence of the voice, following the phrasing of the language, rather than a repeating metrical pattern. The rhythm of a free-verse line is marked by the grammatical and rhetorical patterns of natural speech and by the sequence of the musical phrase.’ Though Kasi Ananthan’s verses in this collection may be classified as free verse, one can also view some samples as Tamil limericks. A limerick, by definition, is an anecdote in verse consisting of five lines with a defined rhyme and rhythm. While a limerick in English is bawdy in sexual context, Kasi Ananthan’s limerick cum free verse samples in Tamil may be tagged as politically bawdy by his adversaries. I remember that the authors of the Broken Palmyra (1989) book, made an issue of Kasi Ananthan’s platform admonition of death to traitors like Alfred Duraiappah and V. Anandasangaree. But it was Kasi Ananthan, and not the human rights prigs, whose right to free thought and freedom was repressed by the government in the 1970s. Among the 28 verses in this collection, I have translated 7 into English below. The captions Kasi Ananthan had given to these are retained. At the end of each verse, I have added short explanatory notes, describing the context. (1) Experience: Grandma admonished: Rather than opening a government party branch Do plant four Moringa branches It will fruit! Worth for some gravy! [Note: Murungai – Moringa oleifera – is a multipurpose tree used in vegetarian Tamil dishes. The punch line in this verse is the usefulness.] (2) Sensibility: A late Tamil poet entered Jaffna again with life Felt pleased to see his statue. ‘Who anointed my statue?’ He inquired… Again he died! [Note: A mocking verse, on the premise ‘If it happens?’] (3) Poor Me!: One minister in England! One in Japan! One minister in China! One in Russia! One minister in Russia! One in Germany! One minister in America! Poor me in a bread queue! [Note: This verse is self-explanatory. The Sirimavo Bandaranaike regime administered ‘belt-tightening’ for the peasants, while the cabinet coterie went overseas on trivial junkets.] (4) Onions!: Somewhere a welcome party is arranged for a Minister – today! Look – the trucks of the Cooperative Store that usually transport onions carry the SLFP minions there! [Note: The use of the word ‘onion’ is a beauty. In Tamil slang, it has an alternate meaning for dumbness/nothingness. It was a favourite derisive word of E.V.R. Periyar, the Self-Respect Movement’s leader.] (5) Barter: When the plane carrying the ‘Sinhala Only’ Minister lands in Palaly (airport) the dignity of Tamils get exchanged in a ship! [Note: Stories circulated via grapevine in the early 1970s that Alfred Duraiappah – the SLFP organizer for Jaffna – acted as a pimp for the ‘fly by night’ SLFP cabinet ministers and the then crown prince Anura Bandaranaike in arranging favors, including sexual, for their entertainment.] (6) Traitor: The government fed militant Tamil youths with bug-infested bread and bad tasting sambal in prison. A Tamil traitor feasted ministers with buriyani rice, fresh honey and milk – in Batticaloa. [Note: This verse is from personal experience by the poet, during his detention and prison term in Welikade jail. The traitor identified in this verse was P. Rajan Selvanayakam, the then second MP for Batticaloa, who was elected on an Independent ticket but joined the SLFP later.] (7) Buddham Saranam Kachchami (a Pali chant for Buddhists): Though a king, who abdicated to become a renouncer Lord Buddha has a statue here! Though a priest, who waddled in racist politics and crowed ‘No for Tamil Rights’ Ratnasara Thero also has a statue here! [Note: This verse exposes the un-Buddhist posturing of the yellow robed priests. One Ratnasara Thero was killed by police shooting in 1966, while leading an agitation against the ‘Tamil Language (Special Provisions) Regulations’.] In his brief introduction to this collection, Kasi Ananthan uses word play with the phrases, kani ilakkiyam (fruity literature) and kari ilakkiyam (charcoal literature). Kari also means dark, bad, or worthless. The complete text is as follows (the dots are as in the original.):

Kasi Ananthan in Politics Kasi Ananthan gained some buzz in the Indian media after Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in May 1991. It transpired that he had met with Rajiv Gandhi on March 5th 1991 as the LTTE’s emissary. On this issue, I contributed the following note, in the Lanka Guardian magazine. Excerpts from my letter entitled [Rajiv] Gandhi Assassination:

In the 1977 general election, when his popularity among the Eelam Tamils was at its zenith, Kasi Ananthan could have easily entered the parliament if he had opted to be a TULF candidate either at the two-member Pottuvil constituency, or pitted against the UNP’s Tamil-token K.W. Devanayagam at Kalkudah constituency. But it wouldn’t happen like that. Kasi Ananthan wanted to dethrone Chelliah Rajadurai at the two-member Batticaloa constituency. This created a problem for the then TULF hierarchy. Rajadurai was the veteran sitting member for Batticaloa since 1956 and had won five elections consecutively. Thus, Rajadurai was preferentially given the TULF ticket (and the ‘rising sun’ symbol), and Kasi Ananthan was offered the Federal Party ticket (and its ‘house’ symbol). Kasi Ananthan’s logic was that he was not keen on entering the parliament via Pottuvil, but he was determined to dethrone Rajadurai (who had then been accused of corruption, electoral malpractices and flirting with other Sinhalese parties against Tamil interests). Ultimately, Rajadurai – blessed by tricks or luck – won that election in 1977, as Kasi Ananthan lost by placing himself third. Eventually, M. Canagaratnam, the TULF nominee who won the Pottuvil constituency, crossed over to the UNP in Dec. 1977. He escaped from an assassination attempt on Jan. 24, 1978, but succumbed later on Apr. 20, 1980. Rajadurai, the sourpuss, also crossed over to the UNP in March 1979. Rajadurai’s opportunistic switch from TULF to UNP eventually vindicated Kasi Ananthan’s stand in 1977. Kasi Ananthan in Chennai In a recent study on Tamil music in Chennai by Japanese ethnologist Yoshitaka Terada, Kasi Ananthan and his Chennai patron N. Arunachalam receive passing mention. Excerpts:

Conclusion When I listened to T.L. Maharajan’s song ‘Prabhakaran vazhi Nillu’, I felt that Kasi Ananthan had answered part of my public appeal made 30 years ago. In the Dec. 1978 issue of Sudar magazine, I made a polite plea that Kasi Ananthan should poetically record the Eelam Riots (Eela Kalambagam, in Tamil). Akin to the Kalingathu Parani (War of Kalinga) composed in the medieval period by poet Jayam Kondar, for composing an Eelathu Parani (War of Eelam), Kasi Ananthan has a vantage view. Thirty years ago, I spent a pleasant evening with Kasi Ananthan at the Sudar magazine office in Colombo and at one point what he mentioned then is still impressed in my memory. He joked that ‘We should possess a bat’s (mammal) view of this world. Hanging on a branch and viewing the world upside-down!’ There is empirical research evidence that eminent creative authors tend to have shorter life spans than their counterparts in other creative achievement domains. Ten years ago, Vincent Cassandro from a sample of 2,102 creative individuals from 36 nationalities (Tamils excluded!) spanning over 2,000 years proved this point. More than 65 years ago, Harvey Lehman counted that the longevity of 244 authors of political poetry (again, probably Occidental poets!) was 64 years. Considering that Kasi Ananthan, the foremost political poet among Eelam Tamils of our generation, has reached the psalmist mark of ‘Three score and ten’ this year is worth an applause. I’ll wish him, ‘Hang on there, Kasi’; We need your poetry.’ Reference Sources Cassandro, V: Explaining premature mortality across fields of creative endeavor. Journal of Personality, 1988; 66(5): 805-833. Hornstein, L. H.(ed): The Reader’s Companion to World Literature, 2nd ed. New American Library, New York, 1973, pp. 201-202. Kasi Ananthan: Thamilan Kanavu, Ragunathan Pathipakam, Colombo, 1968, 70 pp. Kasi Ananthan: Theru Pulavar Suvar Kavikal, Suthantiran Publication, Colombo, 1975, 28 pp. Lehman, H. C: The longevity of the eminent. Science, 1943; 98: 270-273. Sri Kantha, S: Poet of Emotion and Eelam Riots. Sudar (Colombo). Dec. 1978 (in Tamil). Sri Kantha, S: Poetry of Kasi Ananthan. Sudar (Colombo), in 6 parts. From Oct. 1979 to Mar. 1980 (in Tamil). Sri Kantha, S: [Rajiv] Gandhi assassination. Lanka Guardian, Aug. 1, 1991. Terada, Y: Tamil Isai as a challenge to Brahmanical music culture in South India. Senri Ethnological Studies (Osaka), 2008; 71: 203-226. ***** |

||

|

|||