Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Young Tamils Swap Bombs for BlackBerrysby Shyamantha Asokan, Financial Times, October 16, 2009

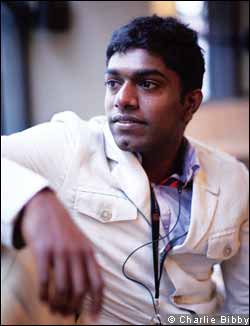

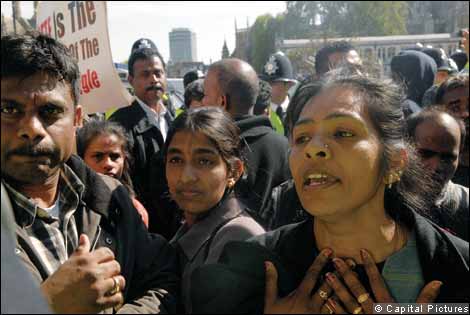

Bala Muhunthan has that high-class hip-hop look: Dolce & Gabbana jeans, tight polo shirt, chunky silver ID tags worn as pendants and an ever-present, ever-beeping BlackBerry. Privately educated in Denmark and the UK, the 22-year-old lives in London and attends a leading business school. Muhunthan spends his weekend nights at members’ bars or parties in Mayfair. Saturday afternoons, he plays golf or football with his friends. “I love London. I love the fast life,” he says. But at the start of April, Muhunthan took a step outside the fast life: alongside thousands of fellow Sri Lankan Tamils, he stood in front of the Houses of Parliament, demanding a ceasefire in Buddhist Sri Lanka’s bloody offensive against Hindu Tamil separatists, which was reaching a violent climax after 25 years of on-off fighting. To Londoners accepting pamphlets from the protesters – whose actions were replicated over the following weeks in Paris and New York – it may have seemed a clear-cut case of might versus right. But the Tamil struggle for an independent state in Sri Lanka has been spearheaded by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) – deemed by the west to be one of the world’s most sophisticated terrorist groups. In the end, the protests were in vain. In May, Mahinda Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s president, declared the final defeat of the Tigers and the conclusion of one of Asia’s longest-running civil wars. The armed struggle for independence had been crushed: in the course of a five-month-long military surge, the Tamil separatists who once controlled swathes of the island’s north and east had lost all their territory. Their infamous leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, was dead. But that ending was also a beginning. Muhunthan, who devoted so much time to the protests that he had to retake the final year of his degree, has, along with many other young Tamils overseas, experienced a political awakening. As one generation of the Tamil diaspora sees its struggle for Eelam, an independent homeland, end in failure, their sons and daughters – who have spent their formative years in the west – are taking up the struggle. But they will fight it on their terms, using their strengths, fomenting a BlackBerry revolution. . . . “Literally every spare minute I have, I spend on this,” Muhunthan said when we met for a cappuccino a month after the downfall of the Tamil Tigers. We first shook hands at the chaotic Westminster protest, where matronly women in saris had guided me to the front of the melee to meet him. Two of his fellow protesters were on hunger strike, wrapped in blankets in Parliament Square. The demonstrators returned to the square every day for almost three months, their numbers peaking at 20,000. We sat down to talk at Cass Business School, where Muhunthan is studying for a master’s degree in banking and international finance. He said that the recent reversal in the Tigers’ fortunes had taken the diaspora by surprise, leaving them bereft. “A lot of Tamils felt that the LTTE was their voice in the war. A lot of people are asking: ‘What are we going to do now?’ People looked to Prabhakaran like he was a god.”

Muhunthan is one of a group of young people who now want to move the separatist struggle into a more diplomatic, PR-friendly – and, they hope, successful – phase. He has recently set up the Tamil Solidarity Movement, a campaigning group that rejects violence. The movement hopes to rely on “networking” with MPs and discouraging western companies from investing in Sri Lanka, rather than on chanting in Parliament Square. As the young man laid out his pragmatic thinking and negotiable aims, it seemed unlikely that they could have co-existed with the Tigers’ suicide bombers and child soldiers. When militants spearhead a cause, they do not countenance shades of grey. But when they fail, hardliners fall away and negotiators can emerge. Analysts point to the Middle East’s Gaza Strip, controlled by the armed movement Hamas, as a territory where such would-be negotiators still lack room to breathe. Muhunthan is certainly upbeat. “At every step, I’m looking at it like a business. It’s about getting any small Tamil groups together to have more power – like merging to form a big company,” he explained. “Then it’s about networking with as many MPs as possible. When I go to see David Miliband, I want to have a huge folder of the names of the people behind me – and I want some big names in there.” He says he has so far convinced more than 140 British MPs to support his campaign. In April, Simon Hughes, a London MP, took him to meet officials at the US State department. Muhunthan hopes his parliamentary backers will persuade the British government to put economic pressure on Sri Lanka until it releases the estimated 280,000 Tamil civilians still held in displacement camps and, ultimately, allows them their own state. Such pressure would include cancelling Sri Lanka’s status as a “GSP+” state, a designation bestowed after the 2004 Asian tsunami and intended to assist recovery by waiving certain taxes on exports to the European Union. The European Union is certainly aware of these calls for a change in policy, and has already launched a probe into Sri Lanka’s human rights record. And, with a preliminary EU report last month condemning the displacement camps as a “novel form of unacknowledged detention”, even Sri Lankan officials now doubt that GSP+ status will be renewed. Muhunthan may be on to something: the tax waiver was one issue he had raised when he met Benita Ferrero-Waldner, the EU foreign affairs commissioner, in Strasbourg this year. . . . In a church hall behind Euston station, near the curry house strip of Drummond Street, the Tamil Solidarity Movement is holding one of its first meetings. It’s a simple affair, with plastic chairs and slices of homemade cake wrapped in clingfilm. But Muhunthan’s fellow TSM members are young, focused, well-qualified and business-minded. Raadhu, an accountant with KPMG, is keen to think of ways to put pressure on the western companies active in Sri Lanka. HSBC has a Sri Lankan division with total assets of $1.4bn – about twice the total foreign direct investment in the country last year. And Sri Lanka’s main export, textiles, has created links with many western fashion retailers. Colombo officials cite Marks and Spencer as a particularly prominent client; M&S says it sources textiles from two retailers in Sri Lanka but refuses to disclose figures. The last thing Colombo needs is an economic cold shoulder. Having pushed up military spending in recent years to defeat the Tigers, Rajapaksa’s government is heavily in the red and hoping foreign largesse will speed its recovery. Sri Lanka’s public debt is now more than 80 per cent of gross domestic product.

“I am very positive about the second generation,” Jananayagam says of the Tamil diaspora’s chances of securing more western intervention. “They are so sure of their status in their country – they were born as citizens there – and they will just ring their MPs or senators to ask for these things.” Articulate and driven, Jananayagam confirms the stereotype of the Tamil diaspora: she used to work as a bond trader at the investment bank Credit Suisse and ran her own hedge fund. She is now busy planning for next year’s British general election; she hopes to persuade MPs to show a commitment to the Tamil issue, and the Tamil community to use their voting power accordingly. . . . The Tamil diaspora’s often middle-class profile, typified by both Jananayagam and Muhunthan, is a legacy of Sri Lanka’s colonial era. Although historical accounts vary slightly, both the north Indian Sinhalese and the south Indian Tamils are thought to have migrated to Sri Lanka more than 2,000 years ago. In 1815, Britain gained control of the whole island (previously split into one Tamil and two Sinhalese kingdoms) and chose to favour the Tamil minority. It was a classic “divide and rule” strategy that pitted ethnic groups against each other to prevent a united fight for independence. Sri Lanka’s Tamils enjoyed education and status superior to that of their Sinhalese peers, and were seen as “career-oriented, intellectual and passive”, according to Neil DeVotta, a US-based professor of political science and author of Blowback: Linguistic Nationalism, Institutional Decay, and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka. DeVotta writes in a separate academic paper that, in 1946, Sri Lankan Tamils made up 11 per cent of the island’s population but accounted for more than 30 per cent of the judiciary, top civil servants and university students. Today, Tamils account for 9-13 per cent of the island’s 20m inhabitants; exact numbers are difficult to confirm as census researchers have not been able to access Tiger territories since 1981. When Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, the Sinhalese majority sought to regain dominance. A new government passed bills that enshrined Sinhalese as the official language, and in the 1970s, universities introduced positive discrimination quotas for Sinhalese candidates. Many well-to-do Tamils headed west, and the diaspora soon became an important crutch for the Eelam campaign. They were able to assist the Tigers in times of financial difficulty – for example, after the tsunami, which severely damaged their territories. Today, up to 250,000 Tamils live in Canada, 200,000 in the UK and 130,000 in the US, although estimates vary widely and these numbers include Indian Tamils. There are also smaller pockets in Australia and continental Europe. “The Tamil diaspora in the US and the UK are not riffraff. You have doctors, you have engineers,” says Peter Lehr, a lecturer in terrorism studies and south-east Asia specialist at the University of St Andrews. “When the Tigers are desperate for money, they have a wealthy group to tap.” However, donations have not always been voluntary – Tamil communities are rife with stories of “when the Tigers come knocking”. Representatives of the group were known for turning up on migrants’ doorsteps and threatening to harm relatives back in Sri Lanka unless money was forthcoming. This created a complex relationship between many Tamils and the Tigers, who became both a guardian against Colombo and a predator on their own community. . . . Despite such reports of intimidation, many first-generation Tamil migrants openly supported the tamil Tigers at this year’s protests. “The Tigers will crush them [the Sri Lankan government],” V.K. Vavanathan, who moved to the UK in the 1970s, told me confidently at the Westminster protest, pounding his palm with his fist as he spoke. Over in New York, S.K. Dhayaparan, a wiry and bright-eyed doctor, stood under the streetlights of 7th Avenue and gave passers-by his pamphlet on the Tigers’ “good intentions”.

So, following the group’s defeat, how do the older members of the diaspora feel? Do they, like some of their children and grandchildren, see recent events as a release from a violent strategy that often made them its victims and that arguably was not working anyway? The London Tamil Sangam, one of Britain’s longest-established Tamil community centres, is entered through a nondescript doorway in Manor Park in the east of the capital. A Tamil enclave, its streets are lined with greengrocers selling jackfruit and branches of India’s ICICI Bank. Saravana Bhavan, a Tamil restaurant chain known for its dosa pancakes, proves a popular draw. Malathy Muthu, the centre’s manager, paints a sombre picture of the older generation, who seem to believe that their cause has been lost. “We have seen a lot of mental health problems – like depression – among the elders,” she says. “This was their dream.” Muthu says several elders are refusing even to leave their houses. “They will not engage with anything. They just stay in watching TV programmes about the ‘at-home problem’. I think they are depressed, although they have not registered it with the GP as they will not talk to anyone.” For those in the diaspora wedded to the armed struggle for independence – sometimes called “the old way” – prospects do indeed seem gloomy. Colombo’s military surge against the Tigers this year coincided with a western crackdown on the overseas activities of the group, which has been banned in ever more countries as the post-9/11 “war on terror” mentality has taken hold. The man alleged to be the Tigers’ UK head, Arunachalam Chrishanthakumar, was jailed for two years in June for supplying the group with electronic materials and military manuals. Karuna Kandasamy, the alleged US leader, is due to be sentenced in New York next month after pleading guilty to charges of making funds available to a terrorist group. Some terrorism experts refer to the Tigers’ proven ability to come back from the brink, and say they could soon resume sporadic guerrilla attacks. But few think they can recreate their former, sophisticated operation. Early attempts seem to be foundering: in August, Colombo said Selvarasa Pathmanathan, the new head of the Tigers, had been arrested. For many first-generation migrants, the task of reinventing a 25-year struggle in their declining years is too great. “The older people think there is no more hope – they are coming to the end of their lives and they think the fight is over,” explained one migrant to the UK, a 57-year-old engineer who did not wish to be named (he was worried about retribution against relatives in displacement camps, which are rife with reports of human rights abuses). “Whether their means were right or wrong, [the Tigers] were the only people who fought for us. They were the voice for Eelam, and look what they did – they built their own air force, navy, everything. We had those things when no one else would help us.” However, the first generation also recognise that their children’s “new way” presents a ray of hope. “The young ones are passionate about the struggle in a way that has surprised their parents,” the engineer said. “And their approach is very different – they want to use democratic and diplomatic means. It’s good. They should not make the mistakes that we did.” . . . In recent months, Sri Lankan officials have been on promotional trips to the US, Britain, Malaysia and Singapore to lure foreign capital to what they say is now a peaceful island. Trips to the Middle East are planned for early next year. “This is an ideal time to look at the investment opportunities in Sri Lanka,” Gamini Lakshman Peiris, international trade minister, told investors at a London briefing this year. “Terrorism is the only thing that has held us back.” The government now hopes to profit from land wrested back from the Tigers by offering long leases on plots in the north and east. These areas contain a region known as “the rice bowl of the country”. Meanwhile, a 350-acre economic zone is planned in the area of Kilinochchi, a Tiger town that fell in January – once the landmines have been cleared. Sri Lanka’s strategic location, at the crux of vital shipping routes to south-east Asia, is undeniable and China has snapped up the rights to develop the island’s once sleepy Hambantota harbour. Beijing is spending $1bn on the construction of a major port, according to Sri Lankan officials, as well as building a 900-megawatt coal power plant in the north-west. The country’s central bank, showing its faith in the investment drive, has upgraded its 2009 economic growth forecast from 2.5 to 4.5 per cent. But amid the bullish statements at the London and New York briefings, Colombo’s ministers have also been reminding the west of its role in securing the fragile peace. Peiris told his London audience that the international community had a “continuing duty” to prevent the diaspora from funding the Tigers’ recovery. This posed the only threat to the island’s “new investment opportunities”, he said. Other Colombo officials insist that economic growth is for the “benefit of all citizens”, and that it is not in the interest of Tamils “at home or overseas” to thwart such progress. But while Sri Lanka refuses to release Tamil civilians from camps, or allow journalists into these sites, there is much to stoke the separatist cause. President Rajapaksa had promised a postwar political settlement with the Tamils, but he has so far made barely any moves on this front. Whether it is through continuing to fund the Tigers in some form, or through the next generation’s “new way”, it seems that the struggle for Eelam is far from over. “Yes, of course, I am disheartened, but we have to reinvent and reorganise ourselves now,” says one campaigner, back in the church hall in Euston, where everyone is packing away the plastic chairs and heading out for a curry on Drummond Street. “And this time we have to do it from outside. From another country.” Shyamantha Asokan is a former FT journalist. She is now a freelance writer based in Nigeria .................................................................. How the Tigers turned to suicide Modern suicide bombing came to international attention in 1983 when Hizbollah activists rammed a truck laden with explosives into a US Army barracks in Beirut, writes Alex Cardno. Four years later, a Tamil Tiger named Vallipuram Vasanthan emulated this attack, driving an explosives-filled truck into a school used by the Sri Lankan Army and causing huge casualties. Vasanthan became known as the first “Black Tiger”, a deadly division of the Tiger armed forces whose remit was to perform high-risk missions including suicide bomb attacks. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) pioneered suicide attacks as a means of assassinating politicians and wreaking destruction on the battlefield. The Tigers developed techniques which are today synonymous with terrorism. Before the Iraq war, they were responsible for more suicide bomb attacks than any other group worldwide. And while Hizbollah was the first group to popularise the use of the suicide bomb, the Tigers invented the “suicide belt”, which is packed with explosives and hidden beneath clothing. According to Peter Lehr, an expert on terrorism at St Andrews University, the belt “was then copied by all terrorist organisations, notably al-Qaeda and other Islamist organisations”. Women made perfect candidates to wear the belt. “Women [in Sri Lanka] are basically untouchable,” says Lehr, meaning “that they can pass through most security gates without being patted down”. In 1991, former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was killed by an LTTE female suicide bomber wearing a loaded belt. But while such tactics had military value, they subsequently helped brand the Tamil Tigers as terrorists in the eyes of foreign governments following 9/11. Second-generation Tamil activists will almost certainly aim to distance themselves from the taint of suicide bombing as they look to engage with the west. |

||||||||

|

|||||||||