Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

On KP's Dilemma and Mandela's Thoughts about Prison Lifeby Sachi Sri Kantha, November 2, 2009

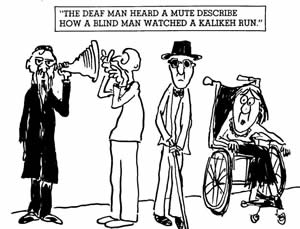

KP in the title refers to Selvarasa (aka Kumaran) Pathmanathan, the presumed leader of the post-Prabhakaran LTTE for 80 days – from May 18 to August 6, 2009. I have been reading the KP-related news items that appeared in the electronic media since May. Predictably, the majority of what has appeared so far has been biased towards the Government of Sri Lanka, and generated by anti-LTTE scribes – the likes of D.B.S. Jeyaraj, B. Muralidhar Reddy and Neville de Silva. Most of these news items are variations on the theme depicted in a cartoon on the Yiddish proverb: ‘The deaf man heard a mute describe how a blind man watched a kalikeh run.’ [kalikeh refers to a crippled woman in Yiddish.], shown nearby.

Lately, I read a contribution by Upul Joseph Fernando in the Colombo Daily Mirror (Oct.28, 2009), under the caption, ‘Why the Sri Lankan govt. won’t allow India to interrogate KP’. Somewhat piqued by the factoids presented in this item, I present my commentary that deals with KP’s current plight in detention. I reiterate that I’m not presenting opinion on KP’s past career under Prabhakaran’s command and the decisions (some of them damaging and dumb to the LTTE’s goals) he made from May to August 2009. This has to be delayed. One of U.J. Fernando’s sentences, “Even today KP is enjoying all the luxurious comforts and facilities while in custody. He is given an Indian cook too to provide him with Indian cuisine, foreign media reveal,” elicited a chuckle. One is not sure whether this was a deceptive leak to enhance the image of the GOSL that they are treating KP with “all the luxurious comforts and facilities.” I thought this was a joke. KP should be allowed to consult an attorney of his choice, rather than being serviced by an Indian cook. Muralidhar Reddy, the Hindu’s servile scribe in Colombo, first reported that, “Minister Keheliya Rambukwella said the new LTTE leader was in military custody and would be questioned about LTTE operations overseas, including foreign assets (The Hindu, Aug. 8, 2009). Reddy subsequently scribbled that KP had released information on the LTTE’s intentions to “interrogators.” But he never identified by names and ranks of these “interrogators”. Here are my 13 questions addressed to reporters like Reddy and Fernando.

Mention of Mandela reminds me of his experiences of prison life, after his incarceration in 1964. His autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (1994) consists of 11 chapters. Cumulatively, it contains 115 blocks. For relevance, I quote excerpts from block 60, for comparison with KP’s current dilemma. I consider these thoughts are inspiration of a higher dimension. After all, Mandela was tagged as a terrorist by his oppressors, as well as publicity-seeking human rights activists like the Amnesty International. On contact with lawyers: “At the end of our first two weeks on the [Robben] island, we were informed that our lawyers, Bram Fischer and Joel Joffe, were going to be visiting the following day. Whey they arrived, we were escorted to the visiting area to meet them. The purpose of their visit was two fold: to see how we had settled in, and to verify that we still did not want to appeal our sentences. It had only been a few weeks since I had seen them, but it felt like an eternity. They seemed like visitors from another world…” On letter-writing: “…The rules governing letter-writing were then extremely strict. We were only permitted to write to our immediate families, and just one letter of five hundred words every six months…” On routine and losing sanity: “Within a few months, our life settled into a pattern. Prison life is about routine: each day like the one before; each week like the one before it, so that the months and years blend into each other. Anything that departs from this pattern upsets the authorities, for routine is the sign of a well-run prison. Routine is also comforting for the prisoner, which is why it can be a trap. Routine can be a pleasant mistress whom it is hard to resist, for routine makes the time go faster. Watches and timepieces of any kind were barred on Robben Island, so we never knew precisely what time it was. We were dependent on bells and warders’ whistles and shouts. With each week resembling the one before, one must make an effort to recall what day and month it is. One of the first things I did was to make a calendar on the wall of my cell. Losing a sense of time is an easy way to lose one’s grip and even one’s sanity.” On Political Challenges and Survival: The challenge for every prisoner, particularly every political prisoner, is how to survive in prison intact, how to emerge from prison undiminished, how to conserve and even replenish one’s beliefs. The first task in accomplishing that is learning exactly what one must do to survive. To that end, one must know the enemy’s purpose before adopting a strategy to undermine it. Prison is designed to break one’s spirit and destroy one’s resolve. To do this, the authorities attempt to exploit every weakness, demolish every initiative, negate all signs of individuality – all with the idea of stamping out that spark that makes each of us who we are. Our survival depended on understanding what the authorities were attempting to do to us, and sharing that understanding with each other. It would be very hard if not impossible for one man alone to resist. I do not know that I could have done it had I been alone. But the authorities’ greatest mistake was keeping us together, for together our determination was reinforced….” Remember that unlike Mandela’s condition in Robben Island, KP’s detention status in Colombo is solitary confinement. On Leadership and Survival in Prison: “As a leader, one must sometimes take actions that are unpopular, or whose results will not be known for years to come. There are victories whose glory lies only in the fact that they are known to those who win them. This is particularly true of prison, where one must find consolation in being true to one’s ideals, even if no one else knows of it. I was now on the sidelines, but I also knew that I would not give up the fight. I was in a different and smaller arena, an arena for whom the only audience was ourselves and our oppressors. We regarded the struggle in prison as a microcosm of the struggle as a whole. We would fight inside as we had fought outside. The racism and repression were the same; I would simply have to fight on different terms…” On Amnesty International: Even during the bleakest years on Robben Island, Amnesty International would not campaign for us on the grounds that we had pursued an armed struggle, and their organization would not represent anyone who had embraced violence.” ***** |

||

|

|||

The vitriol-spitting, slanderous piece by Toronto-based D.B.S. Jeyaraj contributed to the Colombo Daily Mirror (July 25, 2009) entitled, ‘LTTE cabal opposes KP as leader of re-structured Tigers’, before KP’s arrest in Malaysia was nothing but an anti-Tamil hatchet job done to identify diasporic LTTE cadres to their adversaries. In it, he painted KP as a trust-buster. (vide, the sentence: “KP had played tapes of his final conversation with Prabhakaran to drive these points home.”) How did Jeyaraj know that KP had taped his [probably telephone] conversation with Prabhakaran? It seems that Jeyaraj, like Richard Nixon, has a fetish with tapes!

The vitriol-spitting, slanderous piece by Toronto-based D.B.S. Jeyaraj contributed to the Colombo Daily Mirror (July 25, 2009) entitled, ‘LTTE cabal opposes KP as leader of re-structured Tigers’, before KP’s arrest in Malaysia was nothing but an anti-Tamil hatchet job done to identify diasporic LTTE cadres to their adversaries. In it, he painted KP as a trust-buster. (vide, the sentence: “KP had played tapes of his final conversation with Prabhakaran to drive these points home.”) How did Jeyaraj know that KP had taped his [probably telephone] conversation with Prabhakaran? It seems that Jeyaraj, like Richard Nixon, has a fetish with tapes!