Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Tamil VotersBeware of Virulent Viper RAW's Gripby Sachi Sri Kantha, January 5, 2010

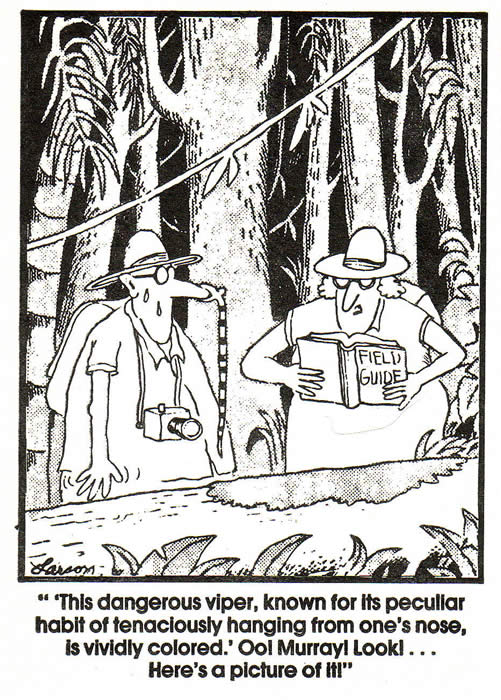

Whether they wanted it or not, year 2010 turns out to be an election year for Eelam Tamils. First comes the Presidential election of Sri Lanka in January 26. Then, one can expect to see the parliamentary elections. In this brief-note, I wish to focus on an unwanted player in the election field of the blessed island. It is none other than the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) of neighbor India. Courtesy of the 1987 Jayewardene and Rajiv Gandhi Accord, since 1988, this virulent viper RAW has played havoc in influencing the polls among the people of the Tamil speaking North-East region. For this reason, I caution the students of recent history not to take the post-election voting analysis of pundits too seriously. None of them take into account RAW’s blatant abuse of Tamil voter rights. Like the Gary Larson’s cartoon on the dangerous viper stuck to one’s nose, Eelam Tamil voters have turned into a pitiable lot.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the CIA was instrumental in rigging elections of many states that were believed to be leaning towards socialist programs. Prior to 1989, the CIA’s counterpart, the KGB’s hands have been caught in election-related funding to Communist Parties in India and Sri Lanka. It seems that RAW has picked up the baton from the KGB. One can grasp that, until now, RAW’s hands were visible in the elections to North-East provincial council elections (held in 1988), and parliamentary elections in North-East (held in 1989, 1994, 2000), but not so in the Presidential elections. Now, for the first time, RAW is up to its trickery in the 2010 Presidential elections. There have been news leaks that M.K. Sivajilingam (a TELO representative), a Tamil National Alliance MP in the current parliament, is set up by RAW to split the Eelam Tamil votes. I’m unable to check the veracity of this leak. On the other hand, in a recent incident, M.K. Sivajilingam was denied entry into Chennai “on the instructions of Indian central government” [Colombo Daily Mirror, Dec. 28, 2009]. A segment of Eelam Tamils consider that among the 22 TNA MPs in the current parliament, Sivajilingam was closest to LTTE leader Prabhakaran. I have long been a critic on the posturings and prophesy of Sri Lanka-born ‘terrorism expert’ Rohan Gunaratna. But, I acknowledge that Rohan Gunaratna’s 1993 book, Indian Intervention in Sri Lanka: The Role of India’s Intelligence Agencies (Colombo, 500 pp) is a noteworthy contribution in exposing RAW’s dirty tricks and a good read. The details presented in this book, one may not obtain from the ream-load of muck lately diffused in the internet by scribes B. Raman, Col. Hariharan (retd.), N. Ram and their ilk. Though the book obviously has a pro-Sinhalese and anti-LTTE bias, here are a few Gunaratna’s revelations. (1) Sri Lanka was staffed by RAW operatives and a station chief from 1970 (p. 21). (2) RAW launched the Sri Lanka operation during the last year of Indira Gandhi’s leadership. This top secret operation was to arm, train and finance Sri Lankan Tamil youth (p. 22). (3) RAW was dearly wrong in its assessment of the LTTE - the most decisive factor in the Sri Lanka operation (p. 26). Gunaratna briefly covered how RAW first rigged the 1988 North-East provincial council election and anointed Varatharaja Perumal of the EPRLF as the chief minister. But RAW’s hand in the Feb.1989 parliamentary election does not receive much recognition in this book. One prominent Tamil politician who was badly bitten by the RAW viper was A. Amirthalingam. He was forced to contest this Feb. 1989 election from Batticaloa. He lost, and ultimately he succumbed from a RAW-promoted assassination squad, within few months. Another interesting aspect of Gunaratna’s book is that the activities of S.C. Chandrahasan, one son of Federal Party-TULF leader S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, receives some amount of exposure. That the stars of Amirthalingam and Chandrahasan faded when they became victims of the RAW viper is now well known. Beginning from Amirthalingam, there is ample material now to write a book on the Tamil political victims of RAW. The January 1, 1994 issue of the Lanka Guardian edited by Mervyn de Silva carried a review of Rohan Gunaratna’s book. The reviewer was none other than Shekhar Gupta, an Indian journalist who was a conduit of RAW’s messages in the media. He was the one who first tooted the RAW story of Tiger training camps in Tamil Nadu in the India Today magazine in 1984. Gupta anoints Rohan Gunaratna as ‘a Sri Lankan writer of repute’. Huh! I presume that this review first appeared in India Today magazine, and Mervyn de Silva republished it, without attributing the original source. For the record, I provide this review below verbatim. IPKF misadventure – biased view by Shekhar Gupta [Lanka Guardian, Jan. 1, 1994, p. 20] One of the key players in India’s Sri Lankan misadventure recently confessed to me that within 48 hours of the Rajiv-Jayewardene accord in 1987, it was painfully obvious to him that India did not have the ‘temperament to become a regional superpower’. On top of the list of the various traits lacking – ruthlessness, ambition, arrogance – was the absence of a Machiavellian intelligence agency that separates also-rans from power players in the world community. The Sri Lankans certainly disagree, considering the effort their own intelligence agencies seem to have put in to make this book possible. Rohan Gunaratna, a Sri Lankan writer of repute, has obviously been given trunk-loads of documents on Indian intelligence activity in Sri Lanka, including RAW’s top-secret correspondence with its Sri Lankan counterpart, the National Intelligence Bureau (NIB). The result is a damnation of India and RAW, which is blamed for everything, from initiating Tamil insurgency to setting up the accord, the war and then plotting against the IPKF as well. The pity is, despite the book presenting a Sri Lankan point of view with a blatant bias, it is partly correct, for the IPKF operation was as much a saga of Rajiv Gandhi’s lack of comprehension of world affairs and the Indian establishment’s myopia on long-term security, as a colossal failure of intelligence. To know more about it, however, you need to go, not to the NIB, but to any of the harried IPKF commanders. Hard intelligence was either not available with RAW, or was not passed on to the IPKF in time. So routine had this become that many in the IPKF had begun to wonder if RAW was not playing a cynical double game, keeping channels to the LTTE open for political gains. Dozens of Indian army vehicles and patrols were blown up over culverts and repeated queries to RAW for road maps of the north-east fell on deaf ears while the most comprehensive maps lay locked up in a cupboard in the agency’s headquarters. Worse was the embarrassment of the IPKF catching suspected Tigers and RAW seeking their release as they happened to be its ‘sources’. The standing joke among Indian officers was: ‘How many RAW agents did you apprehend today?’ Unfortunately, it is this aspect of RAW’s tactical bungling that Gunaratna fails to throw any new light on. But he is extremely accurate in concluding that the Indian policy was not as much to dismember Sri Lanka as to create trouble and extract concessions from Colombo under pressure of a separatist Tamil movement. It squares up with the Indira-Rajiv era politics at home as well: remember Bhindranwale, the Bodo Security Force, GNLF and so on, as also policy failures across the board. But the mistake Gunaratna makes is in believing that those on his side of the Palk Straits are better than the Indian counterparts whose confidence they are betraying to him. If anything, they were even more inefficient as their continuing failure to contain the LTTE or solve the assassinations of several top political leaders shows. Accordingly, if Gunaratna had relied on accounts of Sri Lankan Tiger training camps published in the Indian press rather than on Sri Lankan intelligence, he would have got most of the spellings of places and people’s names right and would not have talked about training camps in New Delhi’s R.K. Puram and Green Park, where it’s difficult even to find parking space. What is of value is the correspondence Gunaratna has unearthed between RAW chief during the IPKF days, Anand Verma, and his Sri Lankan counterpart as well as the details of Verma’s meeting with Jayewardene. But I am not sure which side comes off worse. Also, while talking of bungling and sheer diabolical double-cross, Gunaratna could have mentioned R. Premadasa and the Sri Lankan intelligence under him who provided arms and ammunition to the Tigers while they were being chased by the IPKF. Even Lalith Athulathmudali, who has been quoted copiously in the book had alleged that armaments were sent by Sri Lankan intelligence to the LTTE, and, most ironically, in Tata trucks given by none other than India. Frankly, this is a book an Indian should have written, for the Sri Lankan misadventure is a saga of failure on all fronts: intelligence, policy and politics. For us, in India, the fact that RAW was up to terrible tricks is not such a big issue. In 1971, following the ruckus created by revelations of CIA wrongdoings, US Senator John Stennis, a strong supporter of the ‘company’, had told the Senate: ‘Spying is spying. You have to make up your mind that you are going to have an intelligence agency and protect it as such, and shut your eyes some and take what is coming’. Why RAW failed so miserably, pushing India into a war it never wanted, and yet losing every objective it had set out to achieve while the LTTE carries on, having added the scalps of Rajiv and Premadasa to its tally, is the question that somebody, some day, and on the Indian side, will have to answer.” ***** |

||

|

|||