Footnotes in Gaza

Review by Yousef Munayyer, Palestine Center, February 10, 2010

|

"Palestinians never seem to have the luxury of digesting on tragedy before the next one is upon them. When I was in Gaza, younger people often viewed my research into the events of 1956 with bemusement. What good would tending to history do them when they were under attack and their homes were being demolished now? But the past and the present cannot be so easily disentangled; they are part of a remorseless continuum, a historical blur. Perhaps it is worthwhile to freeze that churning forward movement and examine one or two events that were not only a disaster for the people who lived them but might also be instructive for those who want to understand why and how hatred was 'planted' in hearts." ...

What Sacco affords to Palestinians in this must read book is what Edward Said often claimed they had been denied: "permission to narrate." |

"Footnotes in Gaza" written by Joe Sacco

Hardcover: 432 pages, Metropolitan Books (December 22, 2009)

Palestine Center Book Review No.2 (10 February 2010)

By Yousef Munayyer

In 2001, during the early part of the second Palestinian intifada, Joe Sacco accompanied Chris Hedges on a trip to Khan Younis to illustrate the story of one Palestinian town during the uprising for Harper's magazine. He recalled once hearing of a massacre that took place in Khan Younis and after further investigation, interviews and research, several paragraphs about the massacre that took place on 3 November 1956 were included in the article submitted to Harper's. In 2001, during the early part of the second Palestinian intifada, Joe Sacco accompanied Chris Hedges on a trip to Khan Younis to illustrate the story of one Palestinian town during the uprising for Harper's magazine. He recalled once hearing of a massacre that took place in Khan Younis and after further investigation, interviews and research, several paragraphs about the massacre that took place on 3 November 1956 were included in the article submitted to Harper's.

The editors at Harper's did not find the information about the massacre relevant and subsequently cut it from the published version.

To Sacco, however, the massacre at Khan Younis was too significant to ignore. He was not comfortable with leaving the "greatest massacre of Palestinians on Palestinian soil" as a mere footnote in the history of Palestine. It was this sense of injustice of historiography that drove him to look further, dig deeper and write Footnotes in Gaza.

The title itself refers passively to the outrageous obscurity of the massacres which took place in Gaza in 1956. The wonton killings described in both Rafah and Khan Younis in November 1956 are dealt with in great detail. Sacco decided that these events, these "footnotes", will no longer be subjected to the dismissive whims of editors who sanitize American literature. Footnotes in Gaza is a 432-page addendum to the Palestinian story which is now determinatively etched into the annals of western writing.

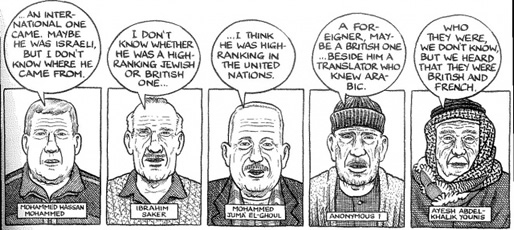

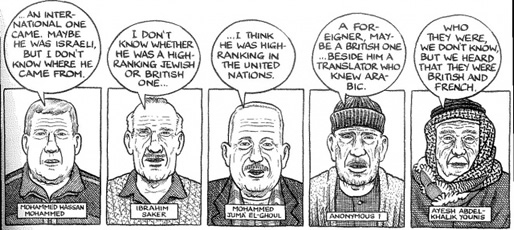

Yet, throughout the book, as Sacco documents his interactions with Palestinians, even they question the relevance of a book on '56 when the transformative events of '67,'73, '88, '00, etc have dramatically reshaped their lives again and again since. His stubborn persistence prevails, however, and he manages, with the help of local guides, to find numerous individuals who testified as firsthand witnesses to the massacres of 1956.

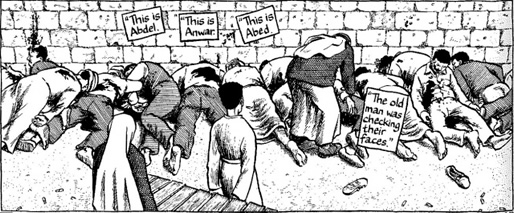

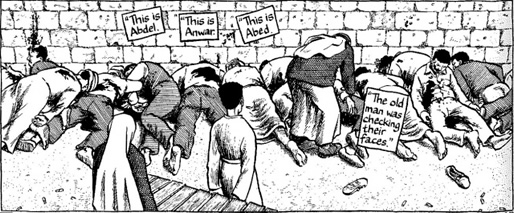

What is unique about this book is its style of presentation. Footnotes in Gaza is a picture book, or a work of illustrative journalism to be more precise. Make no mistake, however, the content is not recommended for young readers. In fact, Sacco sketches the gruesome details of massacre in only the way images can describe, leaving an indelible mark on the memory of the reader that words alone could not accomplish.

It's not merely images of bloodied bodies strewn across the streets of Rafah or shot against a wall in Khan Younis that stick with the reader; It is also the pensive, sometimes horrified, look on the faces of those interviewed as they recall the massacres they saw unfold before their eyes so many years before. It's also the depiction of screaming widows who make the reader look for a volume knob only to realize they are in fact still reading a book.

Footnotes in Gaza is also more than a documentation of the testimonies of survivors of the massacres. It's the story of the documentation as well. Sacco takes us through the journey of navigating Khan Younis and Rafah, living in a refugee camp, the banality of journalism during the intifada and the daily horrors of Israeli occupation.

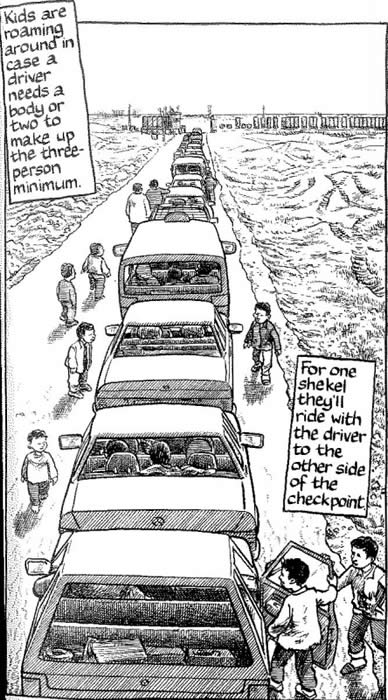

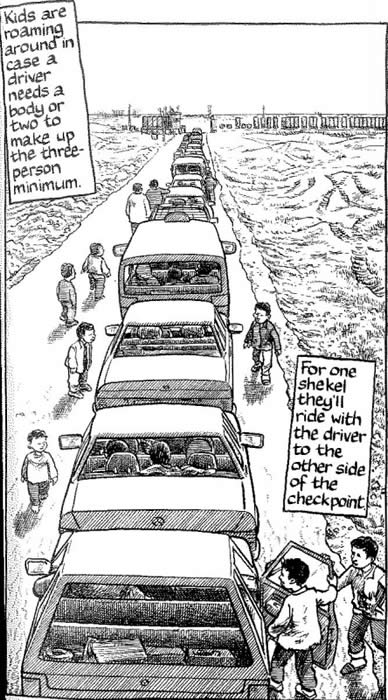

In an attempt to get to Rafah to interview a survivor, Sacco illustrates the long line at checkpoints, which routinely take hours to pass through; the Israeli watch towers, which send bullets over Sacco's head and the children waiting at the checkpoint to ride in under-occupied passengers cars for a shekel so that the cars meet the three-person capacity minimum to cross the Israeli checkpoint. He also documents the ongoing demolition of Palestinian homes along the Philladelphi crossing at Gaza's southern-most border. The author conducted much of his ethnographic research during the worst moments of the Palestinian intifada. The funerals of martyrs are drawn in the book, along with the destruction of houses, the shooting of activists and the protection of colonial Israeli settlements.

It was in fact these modern day realities which led Sacco to pen the following in the introduction to his book:

"Palestinians never seem to have the luxury of digesting on tragedy before the next one is upon them. When I was in Gaza, younger people often viewed my research into the events of 1956 with bemusement. What good would tending to history do them when they were under attack and their homes were being demolished now? But the past and the present cannot be so easily disentangled; they are part of a remorseless continuum, a historical blur. Perhaps it is worthwhile to freeze that churning forward movement and examine one or two events that were not only a disaster for the people who lived them but might also be instructive for those who want to understand why and how hatred was 'planted' in hearts."

As the famed Palestinian political cartoonist Naji Al-Ali once wrote:

"As soon as I was aware of what was going on, all the havoc in our region, I felt I had to do something, to contribute somehow My job I felt was to speak up for those people, my people who are in the camps, in Egypt, in Algeria, the simple Arabs all over the region who have very few outlets to express their points of view."

Where Ali often used faceless or nameless caricatures, or his signature 'Handala,' to convey the feelings of Palestinians, Sacco takes this many steps further by allowing real people to tell their stories in his book. The wives who buried their husbands, the boys who buried their fathers and the men who lay alive and bleeding at the bottom of a pile of terminated humanity, all get an opportunity to tell us their story.

What Sacco affords to Palestinians in this must read book is what Edward Said often claimed they had been denied: "permission to narrate."

Yousef Munayyer is Executive Director of the Palestine Center. This book review may be used without permission but with proper attribution to the Center.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives