Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Right to Free Speech Collides With Fight Against Terror

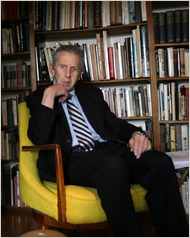

WASHINGTON — Ralph D. Fertig, a 79-year-old civil rights lawyer, says he would like to help a militant Kurdish group in Turkey find peaceful ways to achieve its goals. But he fears prosecution under a law banning even benign assistance to groups said to engage in terrorism.  Ann Johansson for The New York Times Ann Johansson for The New York Times

Ralph D. Fertig, a civil rights lawyer, is challenging a law that bans even benign assistance to groups said to engage in terrorism. The Supreme Court will soon hear Mr. Fertig’s challenge to the law, in a case that pits First Amendment freedoms against the government’s efforts to combat terrorism. The case represents the court’s first encounter with the free speech and association rights of American citizens in the context of terrorism since the Sept. 11 attacks — and its first chance to test the constitutionality of a provision of the USA Patriot Act. Opponents of the law, which bans providing “material support” to terrorist organizations, say it violates American values in ways that would have made Senator Joseph R. McCarthy blush during the witch hunts of the cold war. The government defends the law, under which it has secured many of its terrorism convictions in the last decade, as an important tool that takes account of the slippery nature of the nation’s modern enemies. The law takes a comprehensive approach to its ban on aid to terrorist groups, prohibiting not only providing cash, weapons and the like but also four more ambiguous sorts of help — “training,” “personnel,” “expert advice or assistance” and “service.” “Congress wants these organizations to be radioactive,” Douglas N. Letter, a Justice Department lawyer, said in a 2007 appeals court argument in the case, referring to the dozens of groups that have been designated as foreign terrorist organizations by the State Department. Mr. Letter said it would be a crime for a lawyer to file a friend-of-the-court brief on behalf of a designated organization in Mr. Fertig’s case or “to be assisting terrorist organizations in making presentations to the U.N., to television, to a newspaper.” It would be no excuse, Mr. Letter went on, “to be saying, ‘I want to help them in a good way.’ ” Mr. Fertig said he was saddened and mystified by the government’s approach. “Violence? Terrorism?” he asked in an interview in his Los Angeles home. “Totally repudiate it. My mission would be to work with them on peaceful resolutions of their conflicts, to try to convince them to use nonviolent means of protest on the model of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King.” Mr. Fertig said his commitment to nonviolence was not abstract. “I had most of my ribs broken,” he said, after his 1961 arrest in Selma, Ala., for trying to integrate the interstate bus system as a freedom rider. He paused, correcting himself. “I believe all my ribs were broken,” he said. Mr. Fertig is president of the Humanitarian Law Project, a nonprofit group that has a long history of mediating international conflicts and promoting human rights. He and the project, along with a doctor and several other groups, sued to strike down the material-support law in 1998. Two years earlier, passage of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act had made it a crime to provide “material support” to groups the State Department had designated as “foreign terrorist organizations.” The definition of material support included “training” and “personnel.” Later versions of the law, including amendments in the USA Patriot Act, added “expert advice or assistance” and “service.” In 1997, Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright designated some 30 groups under the law, including Hamas, Hezbollah, the Khmer Rouge and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. The United States says the Kurdish group, sometimes called the P.K.K., has engaged in widespread terrorist activities, including bombings and kidnappings, and “has waged a violent insurgency that has claimed over 22,000 lives.” The litigation has bounced around in the lower courts for more than a decade as the law was amended and as it took on a central role in terrorism cases. Since 2001, the government says, it has prosecuted about 150 defendants for violating the material-support law, obtaining roughly 75 convictions. The latest appeals court decision in Mr. Fertig’s case, in 2007, ruled that the bans on training, service and some kinds of expert advice were unconstitutionally vague. But it upheld the bans on personnel and expert advice derived from scientific or technical knowledge. Both sides appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the consolidated cases in October. The cases are Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, No. 08-1498, and Humanitarian Law Project v. Holder, No. 09-89. The court will hear arguments on Feb. 23. David D. Cole, a lawyer with the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represents Mr. Fertig and other challengers to the law, told the court that the case concerned speech protected by the First Amendment “promoting lawful, nonviolent activities,” including “human rights advocacy and peacemaking.” Solicitor General Elena Kagan countered that the law allowed Mr. Fertig and the other challengers to say anything they liked so long as they did not direct their efforts toward or coordinate them with the designated groups. A number of victims of McCarthy-era persecution filed a friend-of-the-court brief urging the Supreme Court to remember the lessons of history. “I signed the brief,” said Chandler Davis, an emeritus professor of mathematics at the University of Toronto, “because I can testify to the way in which the dubious repression of dissent disrupted lives and disrupted political discourse.” Professor Davis refused to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1954 and was dismissed from his position at the University of Michigan. Unable to find work in the United States, he moved to Canada. In 1991, the University of Michigan established an annual lecture series on academic freedom in honor of Professor Davis and others it had mistreated in the McCarthy era. Mr. Fertig said the current climate was in some ways worse. “I think it’s more dangerous than McCarthyism,” he said. “It was not illegal to help the communists or to be a communist. You might lose your job, you might lose your friends, you might be ostracized. But you’d be free. Today, the same person would be thrown in jail.” A friend-of-the-court brief — prepared by Edwin Meese III, the former United States attorney general; John C. Yoo, a former Bush administration lawyer; and others — called the civil liberties critique of the material-support law naïve. The law represents “a considered wartime judgment by the political branches of the optimal means to confront the unique challenges posed by terrorism,” their brief said. Allowing any sort of contributions to terrorist organizations “simply because the donor intends that they be used for ‘peaceful’ purposes directly conflicts with Congress’s determination that no quarantine can effectively isolate ‘good’ activities from the evil of terrorism.” Mr. Fertig said he could understand an argument against donating money, given the difficulty of controlling its use. But the sweep of the material-support law goes too far, he said. “Fear is manipulated,” Mr. Fertig said, “and the tools of the penal system are applied to inhibit people from speaking out.” |

||

|

|||