Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Postwar, Second Term the Mined Road Aheadby Dayan Jayatilleke, Daily Mirror, Colombo, February 10, 2010

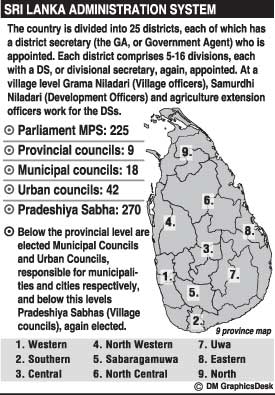

It may sound callous to say this, but Rajapakse would be regarded as the saviour of his nation. Modern nations, especially post-colonial ones, value the integrity of their territory and do not entertain violent sub-nationalisms. India has had its share in Khalistan and in the many struggles in the north-east and continues to have problems in Kashmir. Yet, Indian citizens have allowed their government to ride roughshod over human rights as long as national integrity has been preserved...” The President’s distinguishable takes on the Tamil issue are four fold: village level devolution, the 13th amendment, the 13th amendment plus and a homegrown solution. Now the first and the last – village level devolution and a home grown solution—tend to go together as in a home grown solution that will lead to village level devolution or the other way around. But luckily, as Bess told Porgy (or maybe the other way around), “it ain’t necessarily so”, and the President occasionally indicates that a homegrown solution may result in the Thirteenth amendment plus, meaning the 13th amendment and a Second Chamber. Mahinda Chinthana Mark II (MC2), the manifesto of the Presidential election 2010, for which the President has now obtained a clear mandate, correctly commits him to “implement and improve” upon the 13th amendment. However this is not what the President says in the text of his Independence Day speech this year, the first after the war and re-election: “I am certain that the people in the North and East could stand on their own feet through a solution wrought by devolving powers to the villages and empowering them in the entire country.” (‘Sri Lanka Entering Golden Era of International Relations’, The Island, Feb 5th 2010) Option one has the village as the basic unit of devolution. A variant is the district. This is supposed to be the “Panchayat raj” solution, except that the Panchayat Raj never purported to be a solution for this kind of problem – a problem of the framework of the state and its relations with the constituent communities - but for a different one of making development and governance more participatory of the rural peasantry and the poor. The second and third options (13A and 13A plus) take the province as the basic unit of devolution. The fourth is or seems silent on the unit. An optimist may say that by pitching it low, the President is engaging in a pre-emptive negotiating tactic. The problem with that argument is that we have done this before and gained nothing from it. Instead we lost decades. This was when the UNP administration of President Jayewardene pushed for the district as the unit of devolution but had to settle on the province instead. Today we have the province. So why slide back to the village or district and have to be pushed back to the province by a process of negotiations and external pressure? The first and fourth options require time, because the existing Constitution has either to be amended according to Constitutional methods or a new Constitution has to be drafted and promulgated. From one point of view, Colombo or we the people would therby be “buying” time. From another, which I share with most of our Asian friends, we would be losing time, wasting time. There are several basic problems with the “village level devolution” solution. One is that the problem is not to do with the village; it is not village-sized. The map of the war and that of the recent vote, reveal the contours and dimension of the problem: it is that of the Tamils and Muslims, primarily the Tamils of the Northern and Eastern provinces. It excludes the Sinhala majority areas of the East. It is certainly a provincial or regional level problem. The solution must fit the dimensions of the problem. This much was recognized even by Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in the 1957 Pact with SJV Chelvanayakam. The Tamil nationalities question of the North and East cannot be reduced to fit the Procrustean bed of village or district level devolution by the political equivalent of Procrustean ‘surgery’. The second problem area is that of our international relations and the balance of power. The state of Sri Lanka’s international relations is inextricably intertwined with the state of its interethnic relations. Mervyn de Silva used to say in the 1980s that the world community is interested in two issues: the economic and the ethnic. However, I would add that the salience of the economic has declined relative to the globalization of the market economy model (we are no longer a pioneer of the open economy in statist South Asia) and the dawn of the Information Age with its concomitant strengthening of global civil society has shifted the emphasis from the economic to the ethnic. India has a vested interest in the 13th amendment or a variant, because it is then able to show the people of Tamil Nadu that the solution is something that contains a contribution by Delhi. The consequence of “village level devolution” could be that instead of providing us part of the Asian umbrella that has protected us from the West in all forums, India could dilute its support or stand aside. There are big and medium powers, including in the Third World, who take their cue from the Indian stand. The administration and the Sinhala nationalists simply must grasp that the way in which the world – including Asia – saw the terrorist Tiger secessionists will be very different indeed from the way it will perceive an elected TNA led by the veteran parliamentarian Mr. Sampanthan. The former had little or no legitimacy in comparison with the Sri Lankan state, while the latter may be able to compete in the arena of legitimacy with the Sri Lankan state, especially if state policy reverses existing levels of autonomy and instead offers village level devolution that is unrecognized as a solution to the ethno national question anywhere in the world. The Sri Lankan state must not give the impression that it denies the existence of a problem that the world community recognizes exists, and denies the need for a political solution ( “what political solution?” ) that the international system and world opinion have long agreed is necessary. Worst would be a confrontation between non-violent mass protests by the Tamils, (an old Federal party tradition) honed by a new generation of activists and Western “public diplomacy” training camps, met with the heavy hand or rather, the mailed fist, of the Sri Lankan state (an old SLFP tradition as with Major Richard Udugama and the Satyagraha of 1961)—but captured this time on cell-phone cameras and carried into homes across the world by the international media. When ordinary American citizens are lobbied by Tamil Diaspora activists into calling their Congressmen; when we have a Kashmir or an Intifada in our North and East with Tamil Nadu in sympathy next door, then we will be in danger of losing in the arena of ‘soft power’ that which we won by the resolute exercise of ‘hard power’. We shall have fallen into the trap of our external and narrowly ethnocentric enemies. One can must hope that on his important and long overdue visit to Moscow, President Rajapaksa took time off to ask Prime Minister Putin how he followed up his successful war against Chechen separatist terrorism with the kind of political success in Chechnya. Putin stabilized and pacified the place politically by operating through a young Chechen ally who had partnered Russia during the civil war and represents Moscow. Today, Grozhny, the capital of Chechnya is economically modern and prosperous, the state of emergency has been lifted, and bands of residual or recidivist Chechen terrorists are being engaged in the mountains by the forces of the Chechen ‘president’ Ramzan Kadyrov. Putin did not seek to keep Chechnya united with and within Russia by trying to compete directly with Chechen nationalism on its own terrain in the aftermath of a bloody war. Instead of trying to unite it under his party flag or that of any Russian party, still less proscribe any party bearing the name of Chechnya, he kept it united by granting Chechnya some real autonomy and promoting a pro-Moscow Chechen political option. There is a stated intention on the part of the country’s leadership that ‘everything that was lost to the nation shall be restored’. This is a splendid statement if the vision is one of a multiethnic and meritocratic Sri Lankan nation restoring the standards of its institutions, catching up for thirty lost years as the Chinese did for the “lost decade” of the Cultural Revolution, integrating with the revolution of Asian modernity and the resultant Asian economic miracle. The President also talks of equality, defined in his Independence Day speech as “equality of facilities”. Equality of rights and status as citizens would be as important. As Lord Meghnad Desai writes in his article that is so laudatory of President Rajapaksa: “A nation is whole not just when its territory is single but only when its people feel they all belong to it equally”. |

||

|

|||

...By some device or other, Rajapaksa, whom many underestimated, took the decision that he would end the war regardless of the loss of life involved. The carnage was incredible but in the end, Prabhakaran was defeated and killed. The LTTE’s gamble had failed.

...By some device or other, Rajapaksa, whom many underestimated, took the decision that he would end the war regardless of the loss of life involved. The carnage was incredible but in the end, Prabhakaran was defeated and killed. The LTTE’s gamble had failed.