Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Evil Chasers, Clandestine Crooks and TraitorsA 20th century list – Part 1by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 11, 2010

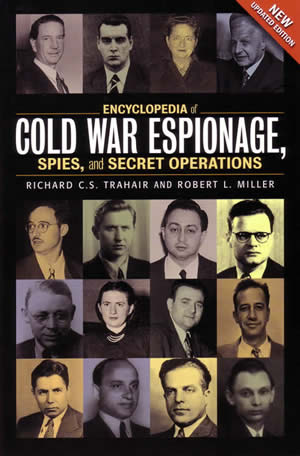

Consider this as a two-part book review-essay. In this part 1, I review the book Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations. In the forthcoming part 2, I focus attention on some facets of the international espionage angle in post-Independent Ceylon (Sri Lanka). “And Jesus said to him, ‘Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. You know the commandments: ‘Do not kill, Do not commit adultery. Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Do not defraud, Honor your father and mother.’ ” [New Testament, Mark, 10:18-19] One of my favorite American cartoons appeared in the New Yorker magazine of May 20, 1996. A guy with dropped jaws is listening to the decision from St. Peter, in front of the Pearly Gates. The verdict in the caption says: “You had more money than God. That’s a big no-no.” If the premise of this cartoon holds, any one who had any links with the good Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) cannot get an OK signal from St. Peter to enter heaven. My proof for this inference comes from Victor Marchetti (a CIA veteran who was in the ‘Company’ from 1955 to 1969) who wrote, “In terms of financial assets, the CIA is not only more affluent than its official annual budget reflects, it is one of the few federal agencies that have no shortage of funds. In fact, the CIA has more money to spend than it needs. Since its creation in 1947, the agency has ended almost every fiscal year with a surplus – which it takes great pains to hid from possible discovery by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) or by the congressional oversight subcommittees.”

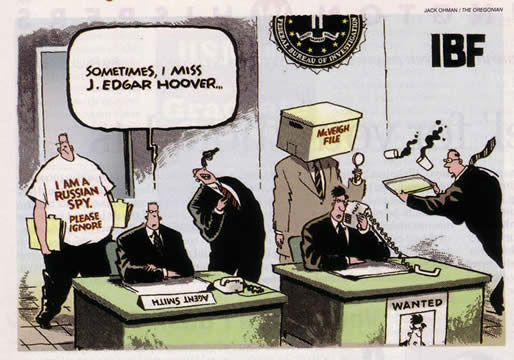

Shakespeare put in artistic, music-loving Lorenzo’s mouth [Merchant of Venice, Act.V, scene 1, lines 91-96], a description on the characteristics of an operating spy in mere six lines: ‘The man that hath no music in himself, nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds, is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils; The motions of his spirit are dull as night, and his affections dark as Erebus Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.’ Three words of the Elizabethan (I) period that appear in these lines need some description: stratagems = violent deeds, spoils = acts of plunder, Erebus = a dark underground region on the route to Hades. It is plausible that Shakespeare’s model of a spy could have been Francis Walsingham (c.1530-1590), one of the principal secretaries of state to Queen Elizabeth, who concocted her espionage circle. Though the Queen acknowledged his services, she kept him poor and without honors. As such, Walsingham died in poverty and debt. Keep in mind that the Merchant of Venice was written during 1596-97, a few years after Walsingham’s death. In our Elizabethan (II) times, I offer the wisdom of humorist Andy Rooney, who elegantly whacked the exploits of these crummy peddlers of deceit. “Spies are, generally speaking, maladjusted social misfits who can’t make a living at anything else. The spies of our country and the spies of the enemy are the same people. They’re interchangeable. When you hear of defectors, it’s almost always spies who defect, not other government officials. Spies defect more often because dishonesty is what they deal in and they get their kicks out of deception.”

Espionage as an Evil-Chasing Establishment Only one hundred years have passed since the first intelligence agency came into being as a government department, financed from government funds. Britain established the first one in 1909. Then other major league players followed suit: Germany in 1913, Russia in 1917, France in 1935 and USA in 1947. Though the CIA per se came into being in 1947, it had two predecessors, the COI in 1941 and OSS in 1942. Phillip Knightley wrote in his ‘The Second Oldest Profession’(1988), “Once invented, the intelligence agency turned out to be a bureaucrats’ dream…Today even the poorest Third World government does not feel it has attained nationhood until it has its own secret service.” One notable feature in the names of intelligence agencies is that, like a raunchy strip-tease performer, these agencies also shed their clothes frequently, put on ravishing new make-up and morph into new alphabet soups. For instance, the CIA’s predecessors were the COI and OSS. The first Coordinator of Information (COI) appointed by President Roosevelt was William [Wild Bill] Donovan on July 11, 1941. Then, on June 13, 1942, President Roosevelt signed a presidential order establishing the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). During the Second World War that was tagged as “a virtually unregulated body, both romantic and daring, tailor-made to the fondest dreams of the covert operation”. By the end of the Second World War, some 25,000 folks were employed by OSS. Four of the later CIA directors (namely Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, William Colby and William Casey) were OSS officers. President Truman disbanded the OSS on January 22, 1946 and created a Central Intelligence Group (CIG), which later morphed into the CIA after the National Security Act came into force on July 26, 1947, and its director had to be a presidential appointee.

The morphing patterns of notorious Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (KGB) formed in March 13, 1954, after Stalin’s death and Laverenti Beria’s execution in 1953, was akin to that of the CIA. The origin of CHEKA, Russia’s state security apparatus was on Dec. 20, 1917. The abbreviation CHEKA was derived from a full, lengthy Russian title: Vse-Rossiyskaya Chrezvychaynaya Komissiya Po Borbe S Kontrrevolitisiey I Sabotazhem [All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage]. In Russian, the word ‘cheka’ means ‘linchpin’. On Feb.6, 1922, CHEKA was abolished by a decree and replaced by the GPU. Then in 1923, when the Soviet republics were federated to form the USSR, the GPU became OGPU. Under Stalin, in 1934, OGPU morphed into NKVD. After Stalin, KGB debuted and continued until 1991. Under Boris Yeltsin, KGB metamorphosed into a new intelligence agency. The book in review, authored by Richard Trahair and Robert Miller, provides a compendium on the roles played by over 300 individuals (Americans and non-Americans) who as spies or as their sidekicks (leash-holding spymasters, agents, lawyers and bucket carriers), took on the espionage role of evil-chasing under the garb of national security and peace keeping, during the 20th century. The book provides short biographies and brief descriptions on the exploits of American, Australian, British, Canadian, Chinese, French, Israeli, New Zealand and Soviet spies who cheated/stole/defected/double-crossed/defrauded/escaped/ peddled lies/ engaged in adultery/ killed and got killed in turn/got executed, all for the duplicitous game of ‘national security’. The big names such as the ‘Magnificent Five’ of Cambridge (Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, John Cairncross, Donald Maclean, Harold ‘Kim’ Philby), defectors to the Soviet KGB (such as Aldrich Ames, Robert Hanssen, George Blake, Edward Lee Howard), defectors to the West (such as Yuri Nosenko, Oleg Gordievsky, Oleg Penkovsky, Dimitri Polyakov), Soviet spymasters (Lavrenti Beria, Markus Wolf), American spymasters (James Jesus Angleton, Richard Bissell, William Colby, Allen Dulles, William Casey, Richard Helms, John Edgar Hoover, Kermit Roosevelt) receive recognition. However, some individuals who engaged in espionage merely make cameo appearances, without special entries in the text. These include, William (Bill) K. Harvey, Richard Sorge, and Rear Admiral Herman Luedke. A few Nobel peace laureates have got entangled with spy agencies and spy operations. While Yasser Arafat receives an entry for his KGB links, two other Nobel peace laureates (Dalai Lama and Lech Walesa) who had proven and circumstantial CIA links are not in the listing. Few other notable omissions in the text who also had OSS (or CIA) links include Dillon Ripley (1913-2001), Julia Child (1912-2004) and ex-dictator of Panama, Manuel Noreiga (1934- ). Dillon Ripley and Julia Child were involved in espionage in pre-independent Ceylon during the Second World War period. In the post-War period, both Ripley and Child transformed themselves as the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and popular American chef respectively. Also missing were entries on prominent Nazi war criminals, who were recruited by CIA for their knowledge on the Soviets. Andrew Gumbel reported in 2001 that “files on 20 Nazi figures, declassified by the CIA show that three war criminals – Emil Augsburg, Wilhelm Hoettl and Klaus Barbie – worked directly for US intelligence. Of these, only Barbie, a Gestapo officer called the ‘butcher of Lyon’ was ever brought to justice. Nine other Nazi criminals received indirect help from the US. Among these 9 were, Guido Zimmer and Eugen Dollman.” [ Independent, London, April 29, 2001]. Excluded are the entries on two women spies, who were associated with two icons of the 20th century; Albert Einstein and Ernesto Che Guevara. It was revealed in 1998 that Margarita Konenkova (1884- ?; code name Lukas), the wife of Russian sculptor Sergei Konenkov (1874-1971) was a Russian spy who had a dalliance with Einstein during 1945 and 1946, and whose mission was to introduce the physicist to Soviet vice consul Pavel Mikhailov in New York (New York Times, June 1, 1998). Haydee Tamara (Tania) Bunke Bider (1937-1967), an Argentine-German, went to Bolivia as an underground combatant, with a mission of infiltrating the presidential circle of the Bolivian government. After being identified, she later joined Che Guevara’s team as a lone female and was killed in an ambush on August 31, 1967 – 38 days before Che’s assassination. Victor Marchetti noted in his book that, though Tania was a Cuban intelligence agent, “it was rumored by the CIA that the East German woman was actually a double agent. Her employer supposedly was the Soviet KGB, which like the CIA, wanted to keep tabs on Guevara’s Cuban-sponsored revolutionary activites in Latin America.” Clandestine Crooks Victor Marchetti provides a good snippet in his chapter ‘The clandestine mentality’ on how CIA trains young recruits. To quote, “A standard exercise given to the student spies is for one to be assigned the task of finding out some piece of information about another. Since each trainee is expected to maintain a false identity and cover during the training period, a favorite way to coax out the desired information is to befriend the targeted trainee, to win his confidence and make him let down his guard. The trainee who gains the information receives a high mark; his exploited colleague fails the test. The ‘achievers’ are those best suited, in the view of the agency, for convincing a foreign official he should become a traitor to his country; for manipulating that official, often against his will; and for ‘terminating’ the agent when he has outlived his usefulness to the CIA.” Such clandestine operations don’t come cheap. CIA in 1948 had a staff of 302; 7 overseas stations, and a budget of $4.7 million. Then, by 1952 the numbers had bulged to a staff of 2,812; 47 overseas stations and a budget of $82 million. It increased to $200 million, according to the statistic provided by Phillip Knightley. As cited earlier, by 2001, the annual spying budget for USA had ballooned to $30 billion. One demerit of this Encylopedia of Cold War Espionage is that it completely omits the escalation of annual budgets of erstwhile spy agencies such as CIA, KGB and their cohorts, while casually tossing some numbers, under the entries of a few convicted spies. For example, Aldrich Ames (1941- ) of CIA received close to $3 million, with another $2million on the way from KGB. Robert Hanssen (1944- ) of FBI was paid an estimated $1.4 million by KGB over 25 years for his treachery. James Durwood Harper (c.1934 - ) had twice received $100,000 and $140,000 from KGB. Edward Lee Howard (1951-2002), the first CIA agent to defect to Soviet Union received $150,000, deposited in a Swiss bank account. Marchetti also provided brief descriptions on the seven basic areas of agent relations, because identifying and using the ‘right’ agent is the key to a successful espionage operation. The seven areas are: spotting, evaluation, recruiting, testing, training, handling, and termination. While an agent (or a crook or a traitor, if you wish so) passes through these seven phases, he/she has to be camouflaged. As such, a scan on the biographies of the clandestine crooks provided in this encyclopedia reveals that they share a few similarities among themselves; (1) For deceit, they had to maintain several identities and names, (2) Occasionally, they leave a false trail, (3) Quite many meet with unbelievable ends to their lives – ‘accidents’, faked homicides, “dying” in prison and suicides appear to be a norm. Traitors Some among the Tamil human-rights barkers circle, despise the use of the ‘traitor’ word. But whether one despises it or not, traitors have been recognized in history, from the Biblical period. A traitor is a traitor is a traitor. The ends faced by some traitor spies are pathetic. They were executed (hanged or shot) in their own countries for betraying the nation’s ‘real or fabricated’ secrets. Here is a list of such traitor spies who were executed, chronologically arranged in the order of their execution. George Armstrong (1920-1941) in Britain Hotsumi Ozaki (1901-1944) in Japan Kim Suim (1924-1950) in South Korea Pyotr Semyonovich Popov (1922-1960) in Soviet Union Oleg Vladimovich Penkovsky (1919-1963) in Soviet Union Eliahu Ben Shaul Cohen aka Kamal Amin Ta’abet (1924-1965) in Syria General Dmitri Polyakov (1921-1988) in Soviet Union For some reason, entries are missing for George Armstrong, Hotsumi Ozaki and Eliahu Cohen in this encyclopedia. Spies or agents of other nations who were executed in countries where they were operating include Margareta Gertruda Zelle (aka Mata Hari, 1876-1917) in France, Isaiah Oggins (1898-1947) in Soviet Union and Richard Sorge (1895-1944) in Japan. Though there are entries for a couple prostitutes, Gerda Munsinger (a German, 1929- ) and Christine Keeler (a British, 1942- ), their professional predecessor Dutch-born Mata Hari failed to receive recognition. Honeytrap Operations The entry on ‘honeytrap operations’ (pp.159-161) was checked curiously by me. The authors state, “A honeytrap is an operation aiming to recruit agents to the secret service with threats to expose their romantic or illicit sexual intimacies and thereby wreck reputations; it is also a means of getting intelligence on foreign nationals by using prostitutes instructed to inform on their customers.” According to the authors, KGB indulges in honeytrap operations to blackmail the operatives of its rival nations. The authors also mention, “The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) tends to deny that it ever uses the honey trap for espionage; there is some evidence that the case of Vitaly Yurchenko refutes this denial, because he was entrapped by a woman and she later published the details.” That the CIA refrains from honeytrap operations should be a lie. A better example than of Vitaly Yurchenko was the case of K.V. Unnikrishnan (a DIG of Indian police on secondment to RAW intelligence agency) who was the head of RAW operations in Madras during 1985-86. Let’s hear from J.N. Dixit, who was involved then in dealing with the Tamil militants. According to Dixit, “In some of my discussions with Lalith Athulathmudali in the first half of 1986, I felt that he was extraordinarily well informed about the personalities in our intelligence agencies and in the Ministry of External Affairs at headquarters who were dealing with Sri Lankan affairs. I reported these perceptions to Delhi. The general comment which I was conveyed was that the Sri Lankan mission in Delhi and the Sri Lankan Deputy High Commission in Madras seemed to be very effective in gathering information and operational intelligence. In the event, my being impressed by the efficiency of the Sri Lankan diplomatic missions was misplaced. The Sri Lankan source of information was a senior operative of our own intelligence agency, Unnikrishnan, who had been subverted most probably by the Americans through a foreign lady working for Pan-American Airlines. His negative activities were discovered sometime towards the middle of 1986, which was followed by appropriate procedural action against him. The fact that the Sri Lankan Government’s advance knowledge about Indian policies and intentions clearly diminished after Unnikrishnan was neutralized proved that he was a major source of information to the Sri Lankans.” Coda Overall, I found that most entries in the book are interesting and entertaining; but coverage was weak on espionage in Asian (excluding China and Israel), African and South American regions. We don’t get information on the activities of gumshoes from India (RAW) or Pakistan (ISI). If only, missing entries recorded in this review had been included, it will be of much value to many. Let me conclude this review by quoting two American Presidents. Harry Truman had lamented: “For sometime I have been disturbed by the way the CIA has been diverted from its original assignment. It has become an operational and at times a policy-making arm of government.” [Washington Post, Dec. 22, 1963]. Then, we have Richard Nixon, who knew his beans on the game of deception, quoted by Nathan Miller: “What the hell do those clowns do out there in Langley? They’ve got forty thousand people out there reading newspapers!” Consulted Sources J.N. Dixit: Assignment Colombo, Vijitha Yapa Bookshop, Colombo, 1998, p. 61. Phillip Knightley: The Second Oldest Profession – Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century, Penguin Books, New York, 1988, pp.1-2, 248. Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks: The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, Dell Publishing, New York, 1975, 4th printing, pp. 78, 141, 243-258. Nathan Miller: Spying for America – The Hidden History of U.S. Intelligence, Paragon House, New York, 1989, p. 384. John Ranelagh: CIA – a history, BBC Books, London, 1992. Andrew A Rooney: Sweet & Sour, Berkley Books, New York, 1994, pp. 201-203.

| ||

Book Review: Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations (Paperback edition), by Richard C.S. Trahair and Robert L. Miller, Enigma Books, New York, 2009, 572 pp.

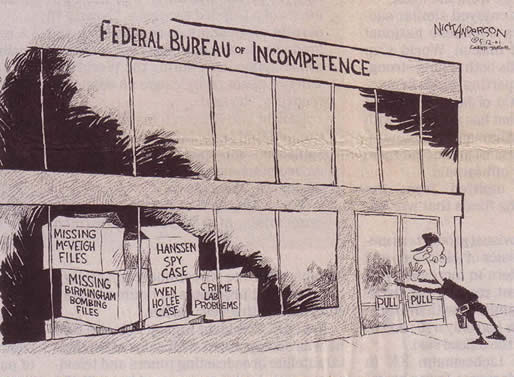

Book Review: Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations (Paperback edition), by Richard C.S. Trahair and Robert L. Miller, Enigma Books, New York, 2009, 572 pp. Here is an excerpt from an editorial that appeared in the New York Times (Nov. 4, 2001), after the Sept.11 incidents in New York and Washington DC. “The failure of the CIA and other spy agencies to anticipate the attacks on New York and Washington was not the fault of a single institution. It was the failure of the government’s entire $30 billion-a-year intelligence apparatus. After five decades of helter-skelter growth, the system is unwieldy and disjointed. There are no less than 13 intelligence agencies affiliated with five different cabinet departments. Any company that was organized this with overlapping divisions, ambiguous lines of authority and no cohesive strategy would go out of business. In the intelligence world, it’s business as usual.”

Here is an excerpt from an editorial that appeared in the New York Times (Nov. 4, 2001), after the Sept.11 incidents in New York and Washington DC. “The failure of the CIA and other spy agencies to anticipate the attacks on New York and Washington was not the fault of a single institution. It was the failure of the government’s entire $30 billion-a-year intelligence apparatus. After five decades of helter-skelter growth, the system is unwieldy and disjointed. There are no less than 13 intelligence agencies affiliated with five different cabinet departments. Any company that was organized this with overlapping divisions, ambiguous lines of authority and no cohesive strategy would go out of business. In the intelligence world, it’s business as usual.”