Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Why Sri Lanka State Has to Adopt a 'Pragmatic Approach'by N. Sathiya Moorthy, Daily Mirror, Colombo, April 1, 2010

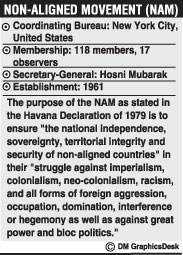

The ongoing diatribe over UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s proposal to appoint an experts’ panel to advise him on Sri Lanka, if allowed to continue, could do more harm than good to the nation than the ethnic war that ended last year. The result of the current exchanges at the global-level could be worse on Sri Lanka over the medium and long terms than what an impartial inquiry could possibly unravel on the human rights front, particularly when contextualized as much to the justification of the ethnic war as much to its conclusion. Whatever is true of Colombo’s exchanges over the UN chief’s decision, or whatever initiatives a global grouping like the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) may have initiated on Sri Lanka’s behalf is also true of the counter-offensive emanating from the country over revived criticisms, purportedly of the West, over humanitarian aspects of the Palestine issue. For starters, it may lose for Sri Lanka the continued friendship of Israel without the Palestine State or its increasingly limited number of friends even in the Gulf-Arab region being able to substitute for the West in certain matters and contexts. It is not about an UN-ordered probe against alleged ‘war crimes’ or other forms of human rights violations. It is not even about UN imposed sanctions that could, if at all, flow from any investigation, if it came to that. Both have a limited approach and a limited shelf-life, even if initiated. Both the processes and the decisions flowing from them could be reversed on a distant date, or an early date – or, even killed in the womb. If taken to the logical conclusion, a tired an old organization like NAM may stand to gain – if they all stand united till the very end – more than Sri Lanka, in political terms. As convergence of interests showed in the Cold War era, NAM’s positions invariably coincided with those of Moscow. Post-Cold War, Beijing may have emerged as a senior and untested partner. Any NAM initiative, if taken to the logical conclusion, could take the issue away from Sri Lanka’s current travails to a situation in which Colombo may not get to hold the cards any more in its hands – or, play the game according to its rules. In this context, it is interesting to note that rebuff of the NAM initiative in this regard came not even from the UN but from the UK. London had earlier blessed Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora groups even at the very launch of the Global Tamil Forum (GTF), with Prime Minister Gordon Brown and Foreign Secretary David Miliband associating with the event. The French, the other P-5 member, does not also seem to share a friendly disposition towards Sri Lanka. The reported decision of Japan to decline UN chief’s invitation to join the proposed expert panel may be limited only to the issue on hand – and need not automatically translate to cover larger tracts. It may be the case with many other friends of Sri Lanka. What more, the Japanese decision may not be able to reverse the mood in the UN, or in global capitals where it matters. It is for Sri Lanka to decide if it would want to be the trigger for a ‘new Cold War’ – with its own implications for the country. If nothing else, in political terms, if not physical terms, the country would become the battle-field for a battle royale, over which it would have no control whatsoever, now or later. Sri Lanka’s purported strategic locational advantage in terms of Colombo’s opportunity to exploit in geo-political terms could well turn out to be a burden and baggage. It would not stop there, though. The current situation is beset with possibilities that could lead to a vivisection of Sri Lanka even as the ‘ethnic war’ could not do over a three-decade long period. Colombo needs to remember that only the ‘terrorist LTTE’ has been militarily neutralized. The Diaspora that provided the propaganda machinery and did its political work overseas remains intact. Better or worse still, they are able to raise their voice and retain their relevance in host nations even better, post-LTTE – and more so, in the absence of LTTE’s terrorist ways. The British engagement with the GTF launch, if it was not an aberration or a political necessity in an election year nearer home, could mean more, and could lead to much more. The fact that the pro-LTTE Diaspora groups reiterated their traditional demand for a ‘separate State’ at the GTF launch – and got away with it -- should be an eye-opener. In the past, they had often referred to the recognition that certain western nations -- the US and the UK included – conferring on Kosovo, and seeking a similar treatment in their case. Western recognition for Kosovo came full 10 years after the war ended in 1999. It also did not follow the war but was re-fixed on allegations of human rights violations and humanitarian excesses. The Diaspora’s continuing reference to ‘war crimes’ and human rights violations need to be read in this context, as well. In Kosovo, the West fought the war. In Sri Lanka, they did not – at least directly. Time used to be when the LTTE held territory and ran what it called ‘civilian administration’, under a military establishment. It had an ‘army’, which in the earlier years of the war, repeatedly out-smarted the armed forces of the Sri Lankan State. If however, none of them helped the LTTE ‘obtain’ a separate State, it owed mainly to the continued absence of ‘international recognition’ of any kind. At no time during those years did the Sri Lankan Government have to worry about the possibility of any third nation conferring diplomatic recognition, and thus global legitimacy on a ‘LTTE-run State’ of whatever kind. At a time when reports began speaking about Eritrea possibly considering it, the ethnic war had ended. Today, the LTTE is not there, but the ‘separate State demand’ is still there. Not all of it is of the Diaspora’s making. For the Sri Lankan State to deny them the ‘territory’ that alone would confer any meaning to their claims, it should carry the Tamil people and polity nearer home with it. It cannot deny the Tamil polity nearer home adequate political space and continued relevance on power-devolution and political solution, and hope to carry them with it, one way or the other. That would mean it is denying much more than what alone may now meet its eyes at the moment. |

||

|

|||

The fact that the NAM, the largest single grouping of UN members, has openly argued against the UN chief and in favour of Sri Lanka should be a dual guarantee for Colombo after persistent hopes that P-5 members like China and Russia would be more than willing to cast their veto vote to clear any UN sanctions or ‘war crimes’ probe against the country. If member-nations abide by NAM’s current position, Sri Lanka could hope to take the UN battle to the General Assembly even if it were to face unforeseen problems in the Security Council. Both are big if’s. Trade-offs are a part of global diplomacy, whether at the Security Council or in the General Assembly, or outside the UN scheme – and there are enough contemporary, post-Cold War instances and examples of the same. .

The fact that the NAM, the largest single grouping of UN members, has openly argued against the UN chief and in favour of Sri Lanka should be a dual guarantee for Colombo after persistent hopes that P-5 members like China and Russia would be more than willing to cast their veto vote to clear any UN sanctions or ‘war crimes’ probe against the country. If member-nations abide by NAM’s current position, Sri Lanka could hope to take the UN battle to the General Assembly even if it were to face unforeseen problems in the Security Council. Both are big if’s. Trade-offs are a part of global diplomacy, whether at the Security Council or in the General Assembly, or outside the UN scheme – and there are enough contemporary, post-Cold War instances and examples of the same. .