Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Rajiv Gandhi’s IPKF FollyBeginning and the Endby Sachi Sri Kantha, May 21, 2010

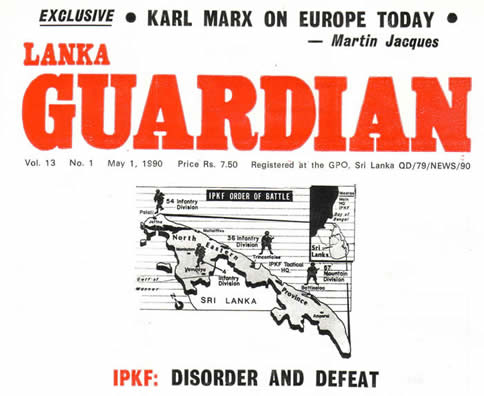

The 20th anniversary of Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) returning from Sri Lanka in March 1990 passed by relatively unnoticed. Here is a roundup of basic facts. In 1990, the ruling party in India was not Congress, the ruling party in Sri Lanka was not the SLFP. Both Congress Party and SLFP were in the opposition then. But, Karunanidhi’s DMK party was in power in Tamil Nadu. He boycotted the return of IPKF soldiers, for political reasons. Today, Karunanidhi’s DMK and the Congress Party are allies and form the ruling alliance. Though both Congress Party and SLFP are holding hands now, during 1987-90 phase SLFP strongly opposed the induction of IPKF. The current leader of SLFP, Mahinda Rajapaksa, was a nominal back-bencher without much gravitas, having returned to the parliament in 1989 after a 12 year gap. I cannot find any record that Mr. Rajapaksa deviated from the party line, and welcomed the IPKF in the island. Politics make strange bedfellows, isn’t it? For this reason alone, I should record the beginning and end of Rajiv Gandhi’s IPKF folly. Many political follies can be listed during the five year period (1984-1989) that Rajiv Gandhi spent as the prime minister of India. Among these, I’d label the induction of IPKF in Sri Lanka as the prime folly. Bofors arms scandal was the second. Propping up Chandrasekhar Singh’s (1927-2007) minority cabinet of breakaway Janata Dal in 1990 and then pulling its political plug at appropriate time on flimsy grounds was the third. Prompting Chandrasekhar to dismiss Karunanidhi’s DMK cabinet in 1991 was the fourth. Prompting the Central Government to dismiss Janaki Ramachandran’s AIADMK cabinet in January1988 was the fifth. The list goes on. For dissecting Rajiv’s IPKF folly, I have chosen to provide 4 items of archival interest that cannot be conveniently traced now, after 20 years.

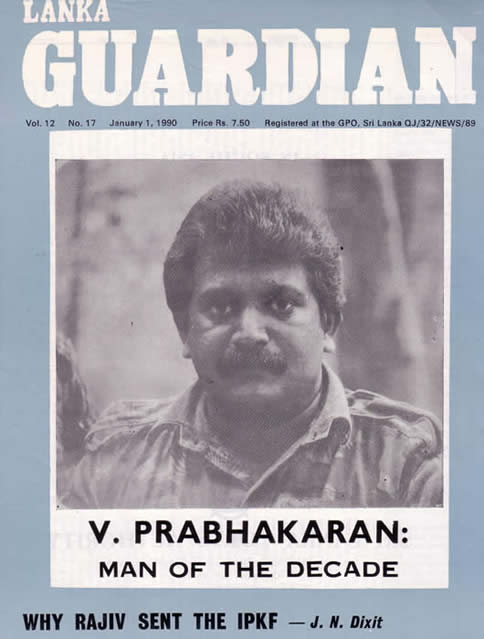

None of these authors can be identified as carrying the brief for Prabhakaran and the LTTE. First, for the ‘beginning’ component, I present the views expressed by J.N. Dixit (the then Indian high commissioner in Sri Lanka), who was involved in inducting IPKF in the island. Previously, I have identified Dixit as one of four individuals (apart from Rajiv Gandhi, J.R. Jayewardene, and V. Prabhakaran) as the main characters in this IPKF drama. As perspectives differ according to the audience constituency (Sinhalese, Tamil, Indian and the rest of the world) of this drama, it is difficult to assign credit as to who were the heroes and who were the villains in this IPKF folly. Then, for the ‘end’ component, I present the observations of reputed Sri Lankan journalist Mervyn de Silva, his son Dayan Jayatilleka and a Time magazine ‘farewell’ report. Mervyn de Silva’s erudite analysis tears apart Dixit’s pro-Indian defence thesis on why Rajiv Gandhi’s folly failed. Simply told, despite the propaganda of New Delhi mandarins and bucket carriers (such as the ‘House of Hindu’ scribes and Indian academics) to New Delhi Brahmins, Rajiv Gandhi was not keen on helping the Eelam Tamils. He acted to guard India’s military interests and the then Congress Party’s political interests. This also partly explains why Mervyn de Silva, among all the Sinhalese, had a ‘soft corner’ for Prabhakaran, and the feature I provide here reinforces this view. While other Sinhalese parties, namely SLFP and JVP, some elements in the UNP including the then prime minister R. Premadasa, the Sinhalese military elements, Buddhist clergy and the jingoist press were vociferous in their anti-India protest, only the LTTE leader stood up to Indian-bullying, in military terms. Dayan Jayatilleka’s piece is also revealing in that while the LTTE got the bum-rap as a spoiler, he shows that the Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord was first spoilt by the grandstanding of Gamini Dissanaiyake (an active proponent of the Accord), who was in his element of racial rabble rousing, and who defended his Sinhala colonization policy by stating that Rajiv Gandhi was made aware of his strategy and Rajiv did not object to it. Among the many commentaries that I have read on Rajiv Gandhi’s politics, I found the one authored by Madhav Das (Monu) Nalapat in 2000 somewhat interesting. It appeared ten years ago in the Economic and Political Weekly of February 5, 2000. He had identified “four distinct phases” in Rajiv’s political career. Phase 1: from November 1980 to mid-1982. In this phase, Rajiv “distanced himself from politicians and tried to creat an alternative route towards implementing ideas.” Phase 2: from August 1982 to June 1985. In this phase, Rajiv “relied on the political class to give him advice as to how things should be got done.” Phase 3: from July 1985 to 1989. In this phase, Rajiv attitude was “Every man has his price. What’s yours? This seemed the motto of the prime minister’s team. Those who did not get ‘persuade’ were sought to be bludgeoned, as the Indian Express newspaper was.” Note that the IPKF folly was instituted during this phase. While all other non-LTTE Tamil militants and TULF were ‘bought’ over, only LTTE remained the stumbling bloc. So, LTTE had to be ‘bludgeoned’ in the words of Nalapat. Phase 4: after November 1989. In this phase, “Rajiv realized that money was not enough. From his defeat, a new personality emerged…This persona reveled in a political role, so much so that the time devoted to his wife dwindled into virtual nothingness. Sonia’s European business and diplomatic friends drifted away, and the Sunday brunches with their continental fare vanished. From 1990 on, it was Indian food rather than pasta that appeared at Rajiv’s table. It was an uncomfortable time for Sonia, who watched as her husband changed into a personality vastly different from the anglicized boy she had married.” I provide a conclusion in the end, reflecting on what Dixit had observed in the final chapter of his 1998 book Assignment Colombo. What Brought the IPKF here? by J.N. Dixit [Lanka Guardian, January 1, 1990, pp. 11-12 & 14] [Note by Sachi: For clarity, I have highlighted the three reasons that Dixit espoused in 1989 for the deployment of IPKF in Sri Lanka. One should give credit to Dixit that he did not mince his words about Rajiv’s chief intention to help the long suffering Eelam Tamils, as some of Rajiv’s apologists (who were anti-LTTE) erroneously propagate after his death.] I am slightly overawed by the audience because I see people sitting in front of me whom I viewed from the lower and middle levels of bureaucracy like General Candeth and I see a number of colleagues with whom I have been associated during my assignment in Bangladesh and then Sri Lanka. I have not brought a written text but had I known that it would be such an august audience, I would have been prepared for a more structured presentation.

I would like to divide my presentation into four sections. The first section is why went into Sri Lanka; what was the nature of our involvement in the island and why. Secondly, what were the internal factors which necessitated our involvement? Thirdly, since I am speaking to the members of the United Services Institution, my perception of how the IPKF has performed in its very crucial role, perhaps, the first of this kind, entrusted to the Armed Forces by the people, and the Government of India. The fourth section of the presentation would be a prognosis on the basis of political developments in Sri Lanka over the last six to eight months after the elections. To begin with, I presume that you know the history of the origins, causation of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka. I will just put it in one sentence the rise of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka was the result of a systematic, orchestrated and deliberate, discrimination against the minority in Sri Lankan society by its majority. You must not forget that Tamil speaking people of Sri Lanka constitute 18% of the population. They also have a higher literacy rate and a greater capacity for economic performance. These very factors which gave them advantageous position during British and pre-British colonial regimes in Sri Lanka, resulted in a backlash from part of the majority against the Tamils and from 1948, when Sri Lanka became independent, there was a consistent policy of discrimination against the Tamils which ultimately resulted in a (caste like) war situation. Every Tamil thought that there was no other way out except to resort to violence to fulfill their aspirations. It is in this context that we have to judge or assess how we got involved. On the outset, I shall give a simple diagnosis; there are many facets, many nuances; we can discuss them when we have the time. But very simply, by 1978 the politically aware Tamils had come to the conclusion that their future lies only in the creation of a separate state, which can be carved out of Sri Lanka, where they can have Tamil as a language and Hinduism as a religion. Tamils have a linguistic identity on which they wanted to create a theory of a new-nation state, not so new to us, because, we went through the trauma of the same doctrine being applied to our country in 1945-46, as a result of which we were partitioned. Since, then our effort and experiment has been to build a society which rejected the theory that the territorial nation-state does not always have to depend on language and religion. That thesis we have rejected. We, in India, have been trying to build on polity based on terms of reference which say that despite its multi-lingual, multi-religious, multi-ethnic nature, an integrated nation can be created; based on principles of secularism and rational precepts of political and social organization and the creation of an infrastructure based on non-religious framework – this does not mean rejection religion but separating religion from the process of politics. So the first reason why we went into Sri Lanka was the interest to preserve our own unity; to ensure the success of a very difficult experiment that we have been carrying out ourselves. We claim to be the largest functioning democracy in the world. Despite what people like Galbraith who say, that India was the largest functioning anarchy in the world, we have succeeded in some measure. And what the Tamils in Sri Lanka were being compelled to follow, in terms of their life, which would have affected out polity. Let us not forget that the first voice of secessionism in the Indian Republic was raised in Tamil Nadu in the mid-sixties. This was exactly the same principle of Tamil ethnicity, Tamil language. So in a manner, our interest in the Tamil issue in Sri Lanka, Tamil aspirations in Sri Lanka was based on maintaining our own unity, our own integrity, our own identity in the manner in which we have been trying to build our society. The second reason, why we went in was to counter the Sri Lankan government over its reactions to the rising Tamil militancy, since 1972. Most of us, look at the 1983 riots as a watershed; from then, some sort of explosion did come. Tamils resorted to violence from 1972 onward and it went on escalating, it became manifest after the 1983 riots, and when the Sinhalese dominated Central Government in Colombo realized that it cannot contain the Tamil militancy on the basis of the means available to it internally, and since they could not look to India for help; because our compulsions were respecting the sentiments of 50 million of our own Tamil sentiments which was quite legitimate from our own point of view. So the, Sri Lankan government therefore, started looking for external support to counter Tamil militancy, Tamil insurgency, which had security implications for us. In the period, between 1978 and 1986, the strength of the Sri Lankan army was raised from approximately 12,000 to 35,000. The overall strength of the Sri Lankan armed forces rose approximately from 15,000 to 17,000, if we include the Home Guards and paramilitary units. Sri Lanka signed informal confidential agreements with the governments of United States and United Kingdom to bring their warships into Colombo, Trincomalee and the Gulf. The frequency of visits by the navies of these countries showed a quantum jump between 1982-83 and 1987. Sri Lanka invited British mercenaries (Keeni-Meeni Services) into its Intelligence services. Sri Lanka invited Shin Beth and Mossad, the two most effective and influential intelligence agencies of Israel. Sri Lanka sought assistance from Pakistan to train its Home Guards, and its Navy, Sri Lanka offered broadcasting facilities to the Voice of America, which would have enabled the United States to install highly sophisticated monitoring equipment on Sri Lanka soil which could have affected our security in terms of their capacity to monitor our sensitive information for their own interests. Sri Lanka bought arms from countries with whom our relations have been difficult. So, the second reason, why we had to be actively involved in Sri Lanka was to counter, to the extent possible, this trend. The third reason why we went into Sri Lanka was an important domestic political factor, and here I would preface what I am going to say by articulating a premise that while morality and absolute norms should govern politics, in actuality it is not so. It cannot so happen, because the human conditions remain imperfect. The chemistry of power, the motivations which affect the interplay of power between societies are not governed by absolute morality. Having said that, I would like to elaborate that we have to respect the sentiments of the 50 million Tamil citizens of India. They felt that if we did not rise, in support of the Tamil cause in Sri Lanka, we are not standing by our own Tamils and if that is so, then in the Tamil psyche, Tamil subconscious the question arose; is there any relevance or validity of our being part of a large Indian political idenity, if our very deeply felt sentiments are not respected? So, it was a compulsion. It was not a rationalized motivation, but it was a compulsion which could not be avoided by any elected government in this country. So, that was a third reason. So, in the first section of our presentation we have found, the need, in terms of our security interests, in terms of domestic politics, and over above, in terms of maintaining our own unity and integrity, to be involved in the crisis of Sri Lanka. Had Sri Lanka been 15,000 miles away with seas in between, like Fiji is, perhaps our involvement could have been less, but it is not. There is just 18 miles of water between us and that is also very shallow. The second aspect of the presentation is how far Tamil aspirations would be fulfilled because of what we did, and I am only going to speak about the political aspects. The Tamils have four demands; that the Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka consisting of the districts of Jaffna peninsula, Vavuniya, Batticaloa, Amapara, Mannar, Trincomalee, these areas should be declared the traditional areas of habitation and homelands of Tamil people. Second, that these areas should be merged in one province; third, that these areas should be governed by a Tamil Government with sufficient devolution of power and autonomy so that Tamils have a sense of security about their own future, in terms of development, culture and all that constitutes functioning of a government for the welfare of its people. The third demand also included equal status for Tamil as a language with Sinhalese in Sri Lanka instead of being relegated to a nonexistent situation as it was after the 1956 Language Act. The fourth, they want significant subjects like finance, land and land settlement, law and order. The Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement signed on the 29th of July 1987 meets all these basis aspirations. It provided for fulfilling these demands to the maximum extent possible. Secondly, with maximum possible speed, the Sri Lankan government between September 1987 and January 1988 passed all the basic legislation needed to transmute what is committed in the Agreement into Government policy and action in Sri Lanka. Third, the package of concessions which is envisaged in the Agreement and which is being granted gradually is better than any package which is being granted gradually is better than any package which the Tamils extracted from the Sri Lankan Sinhalese side over the last 50 years. There were three major agreements signed between the Tamil political parties and the Sri Lankan government between 1948 and 1978. Each one of them was between the existing government of Sri Lanka and majority Tamil political party whether it was a provincial party of Tamils or TULF. Each time an agreement was signed it was scuttled. Whereas the difference this time is that the Agreement is guaranteed by us. The Agreement is underwritten by India, so that the fall-out of their internal chicanery may not be on us, and that guarantee along with a package of concessions which is better than any that they have got, is something which we should take note of. Tamil aspirations are in the process of getting fulfilled. As envisaged in the 13th Amendment of the Sri Lankan Constitution following the signing of the agreement, as envisaged in the Provincial Councils Act passed by the Sri Lankan parliament in October/November 1987, as envisaged in the law passed by Sri Lankan parliament in January 1989, all these four demands, about language, devolutions, merger and homeland have been met. There is an elected Tamil Government existent in the North and Eastern Tamil speaking areas. Because the power had to go to them we have to help them to get it out of the Central Government. Tamil Government exists in the north-eastern provinces for the first time in the contemporary history of Sri Lanka. Secondly, there are between 23 and 25 Tamil members of parliament who will be sitting in parliament, or rather some of whom have already sat there day before yesterday. For the first time, there is a substantive Tamil representation based on rising political groups. So both in the Central Government in Colombo and in the Tamil provinces, there is a Tamil presence. It is not perfect. A devolution which has been already sanctioned under law, has to be made a reality on the ground. Apart from that, the devolution needed by the Tamils, required by the Tamils has to be improved in the field of finance, law and order, control over land and land settlement and so on. But the fact remains, that the terms of reference are in place, even the people are in place, and to that extent, I think, the Agreement, apart from resolving some of our concerns, has concentrated and eradicated the basic reason why this crisis came into being. ***** IPKF quits but coercive diplomacy continues by Mervyn de Silva [Lanka Guardian, May 1, 1990, pp. 3-5]

[Note by Sachi: Sentences in bold, in parenthesis, subheadings and words in large case letters are as in the original. Under the subheading ‘Indian Security’, de Silva uses the generic term ‘Tigers’, which doesn’t mean LTTE alone. This generic term was prevalent and used by journalists until 1985, for all the Tamil militant groups including TELO, PLOTE, EPRLF, TEA and LTTE.] Beautiful Kashmir is worth fighting for, said Mahatma Gandhi in a historic message to the nation in 1947. Though the esthetic principle has been rarely invoked to justify the use of force, K. Subramanyam, the former Director of the Indian Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, does rely on the ‘apostle of non-violence’ to defend the military intervention in Sri Lanka. While the authority cited, the Mahatma, is unimpeachable, it is I suspect the example, Kashmir, the writer has so shrewdly chosen, which really clinches the argument – before an Indian audience. Kashmir, the first intervention of the new independent state of India, is right now the focus of national attention and anxiety.

The Indian Foreign Minister, Mr. I.K. Gujral, has announced that there will no more Indian military interventions anywhere for any reason. Mr. Subramanyam rejects that, and I believe he is right, when he warns: “Let us not rush to the conclusion that this is the last of our foreign interventions. Let us hope and pray that it should be so though one doubts whether the curtain has come down on the Sri Lankan imbroglio and India would not be involved again at all. By all means let us decide that we shall think many times in future before sending our forces into a foreign country even at their invitation.” Subramanyam is a realist. In his contribution to ‘India and its Neighbours’, he accepts, perhaps welcomes all too readily, that “coercive diplomacy has now come to dominate international relations”. It is this ‘coercive diplomacy’ that India has practised with such scintillating success from 1947 onwards. (The India-China war, a conventional clash of arms, was a military defeat that was also a major setback for the Nehru-Menon Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai diplomacy and a notable exception to the ‘coercive rule). Bhutan, Nepal, Goa, Sikkim, Pakistan (Bangladesh), Sri Lanka – all are examples of this ‘diplomacy’ which employed all the instruments available to a nation-state, particularly to a state that has been so naturally endowed that it is the region’s dominant power. These instruments include friendly persuasion, assorted forms of pressure, diplomatic, economic, physical and overtly military. It should be noted that the military has always been used against Pakistan, the neighbour that is least unequal militarily, while Bhutan was persuaded to sign on the dotted line, accepting Indian supervision of foreign policy and Sikkim was ‘incorporated’into the Indian Union. Treaties and ‘Accords’ have legalized the rewards of victory, the accretion of power, while ‘invitation’ has legitimized ‘intervention’. One has however to take a closer look at the term ‘invitation’. This invites a comparison between Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Since I do not buy the ‘plot-PLOTE’ conspiracy theory (that is RAW using Maheswaran’s men as mercenaries to stage a coup in the Maldives, to allow President Gayoom to invite Indian military help), I regard it as a perfect illustration of benign intervention. Not so in Sri Lanka. Main Mission On Sri Lanka, the intervention-by-invitation is flawed because the invitation was a blatant use of coercive diplomacy. The invitation card, printed in India, was air-dropped along with the food parcels and the medical supplies by Indian military aircraft, a fragrant invasion of Sri Lankan airspace. The card was enclosed in a ‘return-to-sender’ envelope on which was written R. Gandhi, Delhi, India. President JR’s response therefore was not of his own free will. An invitation at gun-point is no invitation. Even that would not have proved a major problem for Delhi policy makers and Indian opinion IF the military intervention fulfilled its main mission. What was that? It was former High Commissioner Mani Dixit, a key figure in the pre-Accord drama, who defined it as a necessary ‘projection of Indian power’ to demonstrate to neighbours that they must not permit their foreign policies to undermine Indian security interests. That was the primary objective. The other was to control and contain the Tamil secessionist movement so that it would not rouse passions in Tamil Nadu, the original arena of post-independence linguistic nationalist agitation in India. In past ages, argued Dixit, it was not from the north – the Himalayas were a natural barrier – that hostile foreign forces had entered India but from the sea, the Indian Ocean. (This was also the source of the Indian obsession about Trincomalee and foreign naval presence in this area). In that sense, the Indian interest in the Sri Lankan Tamil community, its grievances, its politics and modes of struggle, was ALSO a national security concern. Sri Lankan Tamil separatism, especially its armed vanguard, represented a threat to national cohesion, a danger to the Indian polity. Indira Gandhi’s fears in short were no different from Leonid Brezhnev’s apprehensions about the Islamic resurgence in Iran and a fundamentalist fall-out which would foment religious discontent and revolt on the Soviet Union’s Moslem periphery. (Recent spread of violence in Azerbaijan is a tribute to his foresight although the Muslim factor may not have been the only reason for full scale Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. Indian Security In any case, the main motivational factor in the coercive diplomacy that led logically to physical intervention was Indian security, not ‘Tamil aspirations’ and ‘Tamil safety and security’. Mrs. Indira Gandhi instructed RAW to train the ‘Tigers’ and equip them so that Delhi could coerce Sri Lanka to grant Delhi’s foreign policy demands, and concede devolution and regional autonomy to the Tamils. The latter exercise would bring political rewards for the LTTE, satisfy the basic aspirations of the Tamil community, and defuse tensions in Tamilnadu, allowing India to repatriate the refugees. Indian diplomacy was sufficiently skilled to give prominence to the Tamil cause rather than to the strategic interest since that strengthened its moral position in the international community. With the possible exception of Pakistan, and a more muted but critical China, the Indian involvement (not intervention) was not denounced. It was ‘understood’ and ‘appreciated’ by both the West, and the Soviet bloc, and of course the Nonaligned ‘bloc’. Mrs. Gandhi’s readiness to allow RAW train other militant groups was also an index of priorities, especially when it became clear that these groups were increasingly fierce rivals of the LTTE, perfectly ready to start a bloody fratricidal war. Mahattaya’s explanation in his interview with this writer therefore rang true – ‘We were too independent’. The armed groups had to remain pliant tools of Indian policy. The LTTE was too ‘independent’, - the word picked by the LTTE’s military commander, when he explained why the LTTE turned to President Premadasa. Most Sri Lankans have forgotten that Prabhakaran began to talk about ‘India’s geo-political interests’ prevailing over ‘Tamil aspirations’ after the Indians failed to persuade the LTTE to lay down arms. Prabhakaran had then read the fine print of the ‘exchange of letters’ that accompanied the Gandhi-JR ‘peace accord’ and understood Indian priorities. How does a nation, particularly a ‘regional superpower’, project its authority over neighbours? The simple answer is that it must successfully impose its will; in Sri Lanka’s case, on the Jayewardene regime that signed the pact and its successors, and on the Tamil militants. Delhi failed to do both. Far from imposing its will, Delhi found Mr. Jayewardene’s successor virtually ordering the IPKF out. Rajiv, the co-author of the Pact, resisted. But President Premadasa did not back down or yield. In fact, he stuck to the letter and spirit of the Accord. The IPKF is here at the will and pleasure of the Sri Lankan President whose orders it must follow. That was JR’s understanding. India also failed to get the LTTE to do its bidding. While many of the anti-LTTE groups became allies and agents of the IPKF, the LTTE took on the Indian army, which soon found that it had alienated the Tamil people who had greeted it as the ‘saviour’. So both on the ground as well as in the sphere of Indo-Sri Lankan relations, Delhi’s policy has collapsed. It was left for prime minister V.P. Singh to recognize this fact and re-negotiate a time table for a final pullout. In other words, a honourable exit, having lost 1,200 lives, with 3,000 wounded. Nobody has so far given a reliable figure on the billions spent. Where does that leave Sri Lanka, the government and the Tamil militants, the ‘Tigers’ most crucially? Embittered Indian policy-makers of the Rajiv era will like nothing better than to see the LTTE and the Sri Lanka army resume their war, with Sinhala opinion in the South turning violently against the Premadasa government. The only question is whether there’ll be deliberate attempts to seek the vicarious pleasures that a Premadasa regime under pressure or siege, may offer. Indian intervention may be over but interference may continue. Much of what could happen will depend on the Colombo-LTTE relationship and how the ‘Tigers’ behave. 1947 (Kashmir) to 1987 (Peace Accord) is four decades of ‘coercive diplomacy’, including intervention, conducted with a consummate skill thatmade the use of force justifiable, even benign and moral. That singular achievement of Indian diplomacy collapsed in the Jaffna and the Wanni jungles. ***** Lessons from North-East Council by Dayan Jayatilleka [Lanka Guardian, January-February, 1999, pp. 2-4] [Note by Sachi: This issue was the last Lanka Guardian issue I received. Though Dayan Jayatilleka’s feature mentions at the end ‘to be continued’, I’m not sure whether it appeared in any subsequent issue of the same magazine. Mervyn de Silva died in June 1999. Despite his antipathy to Prabhakaran and LTTE, in this feature, Jayatilleka highlights five factors that contributed to origin of IPKF-LTTE war in October 1987.]

There is a substantial volume of publications on the events of the years 1987 and 1988 in Sri Lanka, from the negotiations that led to the Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord, the actual signing of the accord, and the entry to the north and east of the island of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), the eruption of fighting between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the setting up in November 1988 of the North-East Provincial Council (NEPC). This part of the present article hopes merely to bring to light one or two lesser-known facts and thereby fill in the blank spot or two. The article as whole is partly a memoir of the author’s own experience as a Minister of the NEPC, and partly an exercise in political analysis of a turbulent period in the island’s current history. Many writers, Sri Lankan and Indian, have written at length on the resistance to the implementation of the Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord of July 1987, and even steps of actual sabotage on the part of the Government of India and the LTTE. That is only a part, perhaps the overwhelmingly larger part of the story, but not the complete one. There were at least three other elements or factors, which contributed to the actual outbreak of war between the LTTE and the IPKF on 10 October 1987, Or, to put it in a more accurate, nuanced manner, three other factors which contributed to giving Velupillai Prabhakaran, leader of the LTTE, an excuse to do what he was intent on doing anyway. The first was the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), which upon re-induction to Sri Lanka following the Accord and the IPKF deployment, initialed a campaign of serial assassinations of Tiger cadres – a course of action that could be termed pre-emptive, if one were charitably inclined. This course of sustained assassinations provided the Tigers with the excuse to re-arm on a significant scale, picking up their recently cached automatic weapons and perhaps more importantly, prompting an influential number of Tamil people to sympathise with the LTTE’s refusal to disarm. The second element was Varadarajah Perumal, the future Chief Minister of the North-East Provincial Council, whose accurate reading of the fascist character of the LTTE led him to the strategic conclusion that a situation must be created in which the IPKF would fight the LTTE. He was to opt for a strikingly similar strategy later, in relation to the Sri Lankan state and the IPKF. Perumal was not the leader of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), but in the aftermath of the Accord, it was he who represented the organization in Colombo which entailed the all important liaison with the Indian High Commission and the Colombo government-cum-security apparatus. The next element that contributed, this time unwittingly, to the unraveling of the Accord was the Indian High Commission itself led by the formidable High Commissioner Mani Dixit. This writer is personally aware that the attitude of the High Commission to the Thileepan fast was one of ‘not blinking’ – and being seen not to blink. Part of this attitude stemmed from ‘establishment’ thinking – ‘we, the Delhi and Colombo establishments shall not let the Accord be put under pressure by these young LTTE yokels; they have to be thought a lesson’. Interestingly, the other wellspring of this hardline attitude was the Indian political culture that the High Commission officials felt themselves heir to: ‘Hunger fasts as a tactic against us – Gandhian Indians – who invented the game? They must be joking.’ The High Commission officials were in no hurry to get to Jaffna and handle the crisis; they were consciously quite willing to let Thileepan die, if push came to shove. In their myopic arrogance what they failed to spot was that Prabhakaran was equally or even more willing to let Thileepan die. The Indian authorities simply fell into Prabhakaran’s psycho-political trap. Gamini Dissanayake, a senior cabinet minister and the strongest supporter of the Accord in Sri Lankan politics, was ironically, one of those who helped undermine it. Dissanayake’s sponsorship or patronage of the Weli Oya settlement, on the border between the North Central Province, and the Trincomalee district, in the very aftermath of the signing of the Accord, clearly went against its spirit – though he told this writer in 1988 that it was done after Rajiv Gandhi was informed and without any objections from him. The Weli Oya settlement, however valuable and even imperative from a geo-strategic point of view, should have been completed before the Accord or postponed till sometime after, but never undertaken at the time it was. It not only played into the hands of the Tiger propagandists in the period before the outbreak of war with the IPKF, it was one issue that incensed all the Tamil groups and helped lend an anti-Sinhala cast to the NEPC/EPRLF’s behaviour. Then again, another element unhappy about the Accord was of course the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the Indian equivalent of Washington’s Central Intelligence Agency. In the final decisive arm twisting operation that took place to soften up the Jayewardene administration into signing the Accord, the RAW was given the task of hammering the cadres of the Eelam groups based in India into an unified expeditionary force under a joint command, equipped with SAM misiles, SAM 7s and officered by RAW personnel. While this was being done, the Colombo government caved in and the process that led to the signing commenced. The expeditionary force preparations were a high point of the RAW activity and influence in the Sri Lankan crisis at least until the RAW activity and influence in the Sri Lankan crisis at least until the RAW chief Anand Verma’s negotiations with J.R. Jayewardene, when the Accord and the IPKF operation was in crisis in late 1988. From the days of the expeditionary force, there was a steep drop in the influence of the RAW in the decision making processes in Delhi – especially after things went very wrong and fighting broke out between the Tigers and the IPKF on 10 October 1987. While all the above mentioned elements helped the Accord to go into crisis, wittingly or unwittingly, they were at play within a matrix that was already severely flawed. Colombo, Delhi and the Tamils had radically different views on what the Accord was all about and, what is worse, each side trumpeted its own version even as the ink on the document and the blood on the streets of Colombo had hardly dried. President J.R. Jayewardene announced that the Accord would bring peace to the country. Gamini Dissanayake told the Sinhala audience on Rupavahini, Sri Lanka’s state television channel, on the day that the Accord was signed, that it was a better deal for the Sinhalese than the 19 December 1986 proposals, since the latter entailed the excision of the Ampara district. Meanwhile, Rajiv Gandhi told a public rally in Tamil Nadu – footage of which appeared on Sri Lankan television – that the Accord obtained for the Tamils more than they had asked for. Perceptions of the Sinhala and Tamil constituencies, were not sought to be reconciled and were swiftly enough, more skewed apart than the Accord could bear. Contrary to the views of the prejudiced, Prabhakaran’s speech at Sudumalai was not a declaration of intent to undermine the Accord. It was a perfectly positioned, tensely poised statement accurately reflecting the diminished space that the man found himself in, a temporary lack of balance but considerable determination and focus to get out of the trap. The Thileepan fast was one of Prabhakaran’s manoeuvres to prise open the space he was trapped in as a prelude to breaking out of that trap completely. Years later, under the Ranasinghe Premadasa and Chandrika Kumaratunga administrations, Prabhakaran was to initiate the war before the peace process reached the point it did in 1987, putting him off balance. Never after 1987, was he to let himself be off balance and pushed politically into that small space and tight corner again. The factors and contradictions among the pro-Accord forces, enumerated above, eventually provided, the opening for Prabhakaran to break out on 10 October 1987. The contradictory bombast with which the Colombo and Delhi governments heralded the implementation phase of the Indo-Lanka Accord contrasts sharply with the sobriety and professionalism with which James Baker handled the highly complicated El Salvadoran settlement in which the historic allies and foes of the USA, and strong ideological and nationalistic sensitivities were involved. The other Central American peace processes, the Madrid peace conference on the Middle East and the Kampuchean process in which China played a major role are all examples of far more sensitive, sober, professional and therefore relatively successful handling of politico-diplomatic efforts at conflict resolution. A landmine that was embedded in the Accord was the provision concerning the permanent merger of the North-East subject to a referendum. That was possibly the only way to get past the dogmatism of the Tamil groups concerning the merger, but it also meant that long before the setting up of the NEPC and certainly the advent of the Premadasa administration, the non-LTTE organizations had decided that the referendum should be prevented. It is noteworthy that the Eelam Left was every bit as allergic to the referendum as the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO). It really didn’t matter to the LTTE, which placed no importance on the Accord despite the fact that such a referendum was often advocated by Lenin, for similar situations. True, there were charges of state-aided colonization having changed the population balance, but that was just cause for insisting on certain detailed modifications in the arrangements for holding a referendum and not for near hysterical allergic reaction to the very idea. The hostility to the referendum soon turned into a determination to pre-empt its holding – and this is one of the factors that fed into the Cyprus – Bangladesh scenario – the Turkish partition of Cyprus, and the Indian intervention which ensured the triumph of the separatist struggle in East Bengal – that began to crystallize before the setting up of the NEPC in late 1988. Indeed these were the rails on which the NEPC experiment was doomed to run. The period between the outbreak of the war and the holding of the NEPC ‘elections’ lasted a shade over a year. The interaction between Delhi and Colombo that resulted eventually in the installation of the NEPC, has been exhaustively set out by authors as authoritative, albeit antipodal, as J.N. Dixit and K.M. de Silva in their respective volumes. What needs to be added on to that composite picture is an awareness of the unchronicled, undocumented processes that were ongoing at that time. These processes ran through three different levels or planes and three different theatres. The three levels were those of the top leaders, the area leaders and the militants on the ground belonging to the non-LTTE groups that were to comprise the council, chiefly the EPRLF. The three theatres were Colombo, the North-East and Delhi. Taken together, we may glimpse the processes operating on both horizontal (Colombo, Jaffna-Batticaloa, Delhi) and vertial (top leaders, area leaders and militants) axes. For instance in the North-Eastern theatre what was going at the level of the top leadership was distinct from an indeed kept a different time as it were, from what was happening at the level of the cadres. When K. Pathmanabha, leader of the EPRLF, visited the East there was a genuine groundswell of popular support, albeit from the old ‘mass base’ of the EPRLF which he had done so much to build through the relief and rehabilitation work done by volunteer youths led by him in the Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students and General Union of Eelam Students (EROS/ GUES) days after the cyclone of 1978. However, Pathmanabha’s presence was not a permanent one, for three reasons: he had not yet been amnestied by the Sri Lankan state, his wife was in jeopardy from the LTTE and his presence was needed to lobby politically in Delhi and Madras. The permanent presence was of local leaders, like the redoubtable P. Kirubhakaran (EPRLF politbureau member and later a minister of the NEPC) based in Batticaloa. His role and function turned out to be a classic counter-insurgency one, which far from bringing the kind of popularity that Pathmanabha’s tours brought the organization, actually tended to work in the opposite direction. This was almost –but not entirely inevitable – given the situation he found himself in and the attendant responsibilities thrust upon him. Kirubhakaran’s problems were the same that area leaders of all the Eelam National Liberation Front (ENLF) groups found themselves in. The point was that the cadre of these groups had rides back to their home bases, piggy-backing on the IPKF flights. Once back they either had to kill or be killed by the LTTE. They also hat to eat and be housed. There was only one way to do that: to function first as spotters and then as irregular auxiliaries for the IPKF. The guns for their self-defence, the food for the boys were all courtesy the IPKF – which underscores the point made earlier in this article, of the weakened state of these organizations. The area leaders became, of necessity, the intermediaries with the IPKF top brass in the locality – a natural division of labour, since the area leaders were functionally proficient in the English language and also possessed the necessary political sophistication. It was also the case that in order to strengthen their access and lobbying capacities with the local IPKF brass the area leaders sought alliances with those few members of the local elites who had not gone along with the LTTE. The alliance in Batticaloa between Kirubhakaran and Sam Tambimuttu (head of the Citizen’s Committee and several Human Rights Organisations, subsequently an EPRLF parliamentarian) was a classic case in point. ***** Goodbye – and Good Riddance by Lisa Beyer [Time, April 2, 1990, p. 32] When Indian peacekeeping forces arrived in Sri Lanka nearly three years ago to try to end a brutal civil war, exultant crowds greeted them with flowers and handshakes. But when the last batch of 2,000 soldiers trooped onto a waiting ship at the eastern port of Trincomalee last week, completing a six-month withdrawl of 70,000 men, not a single civilian showed up to bid them goodbye. If the locals had anything to say to the ‘peace-keepers’, whose presence brought not peace but one of the bloodiest chapters in Sri Lanka’s already violent history, it was more like good riddance. Said A. Sivalingam, a retired senior government official in Trincomalee: ‘We don’t know what the future will bring, but we are glad the Indians have gone’. The final exist of the Indian forces has defused one of the Sri Lanka’s most combustible issues. But the pullout also created a power vacuum in the island’s north and east that was quickly filled by the militants the Indians had been fighting, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, who have yet to renounce their goal of a separate state for the country’s minority Tamils. For now, the separatists and the central government in Colombo are working in concert for peace, but their alliance is anything but stable. Meanwhile, Indian military leaders were pondering why things had gone so wrong in their rough equivalent of America’s debacle in Vietnam. Invited into Sri Lanka by then President J.R. Jayewardene, the Indian army’s original mission was to collect arms from Tamil militants, who had been trained and equipped by India in the first place. In exchange, Jayewardene promised that the 2 million Tamils, who have suffered discrimination at the hands of the majority Sinhalese (11.8 million), would be given more autonomy over a new created Northeastern province, where they predominate. But when the Tigers refused to give up the fight, the Indians became embroiled in a guerrilla war that left 6,000 civilians, 1,200 Indian soldiers and 88 Tiger fighters dead. ‘It was none of our business to send in our army, and when we did, we were so ignorant of the realities on the ground’, lamented an Indian major general last week. Pointing to a copy of historian Barbara Tuchman’s book on misguided military adventures, The March of Folly – from Troy to Vietnam, he said, ‘We can add Sri Lanka to that’. India’s presence in Sri Lanka’s north-east inadvertently brought even greater misery to the country’s south. There, the extremist People’s Liberation Front (JVP), a Sinhalese chauvinist group, protested the foreign intervention with a barrage of murders and strikes that created near anarchy. The government replied by dispatching death squads to assassinate suspected JVP cadres. The retaliation campaign worked – since late last year the JVP has been virtually inactive – but at great cost. In all, some 17,000 people died in the attacks and counterattacks. Pressured by Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa, who succeeded Jayewardene in 1989, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi agreed last year to withdraw Indian troops. The departure was hastened by Gandhi’s ouster in elections last November. His successor, V.P. Singh, takes a less muscular approach to foreign policy. Said a senior aide to Singh: ‘We are glad to get out. We were not wanted there.’ With the foreigners gone, Premadasa’s government and the Tigers are stripped of the shared mission that brought them together last summer. What’s more, the future is mined with potential conflicts. Colombo, for example, wants the Tigers to disarm before elections are held later this year for the Northeastern Provincial Council. Because they have both systematically demolished rival Tamil groups and gained credibility for fighting the Indians, the Tigers are almost certain to win the balloting. But they are loath to surrender their weapons for fear of being attacked by government troops. In addition, it remains to be seen how long an organization that has waged a war for secession can get along with a central government that objects to it. One development that has improved the odds for peace is Colombo’s acceptance that it must genuinely redress discrimination against the Tamils. ‘The President is absolutely committed to devolving power to the minorities’, says Education Minister A.C.S. Hameed. Premadasa’s administration is, among other things, drafting legislation that will ensure all ethnic groups a proportionate share of government appointments and promotions. The current spirit of conciliation, however fragile it may be, has made many Sri Lankans philosophical about their country’s unhappy experience with Indian troops. ‘It was the great hubris that put everybody in their place’, says Radhika Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan political scientist. ‘India realized the limitations of hegemonistic ambitions, the Tigers realized the limitations of armed conflict, and the Sri Lankan government realized the danger of keeping its society divided’. Now the challenge is to make sure those lessons are not forgotten. ***** Congress (I): Crisis of Leadership by Prabhu Chawla [India Today, May 31, 1990, pp. 37-41]

[Note by Sachi: This not-so-flattering feature reveals that, after he was dethroned as the prime minister, Rajiv rarely appeared in the parliament as the leading opposition figure. Chawla also assailed Rajiv’s vacillation, indecisiveness and ambivalence on the secularism issue, and concluded that the preference of then 100-odd Congress MPs from south India, to have “anybody else as the party leader” was a decisive factor. Thus, rather than protecting Eelam Tamils from Sinhalese, Rajiv was keen to protect his political base and his own derriere so that he could remain the leader of Congress Party.]

Gimmicks, high drama, braggadocio have always been the instruments employed by out-of-power Congress (I) leaders in order to continue to hog the headlines and remain in the public eye and the nation’s political consciousness. The memories of Mrs Indira Gandhi riding an elephant in Belchi, Bihar, in 1978 during a mass contact programme, or of Sanjay Gandhi and his street fighters defying the police on Delhi’s Janpath are still vivid.

So it was not exactly out of character for Rajiv Gandhi to plan a 12-hour fast at Rajghat to focus attention on ‘national integration’. It did seem a little incongruous that he should display this colicitude for Gandhian methods within a week of announcing a high tea for Oxbridge alumni on the lawns of the Indian International Centre. But it was yet another pointer that Rajiv Gandhi and his party are struggling to establish a new post-electoral identity. But they haven’t quite got there. The big start in this exercise was supposed to have been the all-party meeting on Kashmir to highlight the failures of the National Front Government. But Rajiv Gandhi, much to the embarrassment of his party, wound up throwing tantrums instead of the fiery polemics that were expected, and carved out for himself a media image of brat rather than statesman. But there’s always that second chance. So, with the planning of the national integration fast, it was a case of once more into the breach, dear friends. Except, this time around, Rajiv is not quite sure who his friends are and to what extent his defeated party will continue to follow him. And his entire approach now smacks of uncertainty and political schizophrenia. For example, he was supposed to move into the posh new AICC (I) office, Jawahar Bhawan, some months ago from the present rickety party headquarters, but has refused to do so lest the move should refurbish his 21st century image that played havoc with electoral fortunes.

Out of power for five months, Rajiv does not seem reconciled to his fate. The illusions of power persist – his imperiousness showing up often; his hosting an ‘Iftar’ party for foreign diplomats, conventionally considered to be the privilege of the prime minister; inviting his former Special Protection Group guards for tea at his residence, disregarding the fact that they are still in service; summoning former foreign secretary S.K. Singh for a meeting following his resignation; making absenteeism from the Lok Sabha a habit notwithstanding his being leader of the Opposition. The tactics can scarcely be said to have helped the political resurrection of Rajiv or the rejuvenation of the Congress (I) which has long been in a shambles. And the rumbles of dissent are growing louder. Leaders hitherto not even remotely connected with dissidence are veering round to the view that Rajiv may be incapable of leading the party. There’s no open revolt. In the Congress culture, that’s always the last straw. But the straws are everywhere in the wind. Disenchanted by the party’s functioning, veteran leader Umashankar Dikshit sent in his resignation from the Congress Working Committee. Dikshit complained that his hope that Rajiv would change his style of functioning after the poll defeat had been belied. Balasaheb Vikhey Patil, president of the newly-launched Congress Forum for Action, is known for his proximity to former finance minister S.B.Chavan, who makes no bones about his antipathy to Rajiv. Another MP associated with this forum, Bagun Sumbrui, is a protégé of Bihar party unit chief Jagannath Mishra. Mishra is still a loyalist, but the fat that supporters like Sumbrui are tugging at the rope is indicative of the pressures on the loyalists to distance themselves from Rajiv. The forum is holding a convention in the capital later this month. The proxy war has already begun. The disenchantment, increasingly showing up among Hindi heartland Congressmen, stems partly from the fact that as leader of the largest single party in parliament, Rajiv has scored few or no successes against the party in power. During the last two parliamentary sessions, the Congress (I) has won only a few skirmishes, the most recent one when, in response to criticism by Congress (I)’s Vishvajit P. Singh of Minister of State for Home S.K. Sahay’s gratuitous reference to a religious community by name, the ruling party offered its regrets. But for the most part, the Congress (I)’s performance has been characterized by the bellicosity of a few MPs rather than any sustained, convincing or clear-headed critique of the National Front Government’s performance on major issues like Kashmir, Punjab and communalism. The Kashmir issue alone should have provided Congress (I) political cannon fodder because of the National Front Government’s confused and indecisive handling of the problem. But confusion can only be fought with clarity. The problem with the Congress (I) is that on this issue it is just as confused as the ruling front it seeks to criticize. Rajiv and his spokesmen alternatively blame Pakistan and Governor Jagmohan for the problems in the valley. In blaming Pakistan they dub New Delhi as weak-kneed and demand a crackdown. And when the governor cracks down on militants, they blame him for displaying the toughness that their own party has been demanding. And the party is hopefully divided over the issue of a more aggressive posture towards Pakistan. Contrary to the official Congress stand criticizing the ‘war hysteria’, Vikhey Patil and several others recently issued a statement indirectly supporting an attack on training camps in Pakistan – just what the BJP demanded. On Punjab, the Congress (I) cannot make up its mind on whether to support continuance of President’s rule or early elections. And it was waffled on the Ram Janmabhoomi issue. What has, however, intrigued partymen most is the leadership’s ambivalence on the issue of secularism. A section of the Delhi Congress (I) unit was clearly associated with the Shankaracharya of Dwarka in his preposterous movie to lay the temple foundation at the disputed site in Ayodhya even when the militant Vishwa Hindu Parishad was respecting the four-month suspension of its own move in this regard. Swinging to the other extreme, Rajiv himself lashed out at the BJP charging it with ‘spreading the poison of communalism in every corner of India’. The workers are left wondering which among the signals they are receiving are correct even while its spokesmen were criticizing the BJP as the main culprit responsible for fanning communal fires in the country. But what made loyal Congressmen really angry was the party’s opportunistic pro-Om Prakash Chautala stand. While the BJP and a large number of Janata Dal leaders were demanding the Haryana chief minister’s resignation, the Congress (I) high command discouraged its Haryana unit from making Meham an issue in the state. In fact, the Congress (I) in Meham accused the leadership of softpedalling the entire issue. And when the official leadership crumbled under pressure, it was Bansi Lal who took the cudgels on behalf of anti-Chautala Congressmen by launching his own organization in the state. And for some inexplicable reason, Rajiv was unable to play the one anti-government card that would have earned his party major public dividends – attacking the unprecedented spiral in prices over the past few months. The advantage, by default, went to Prime Minister V.P. Singh, who quickly cashed in on the follies of his own government and crisscrossed the country attacking the price rise and threatening retaliation against hoarders. The most obvious symptom of the leadership vacuum that’s developing is in Parliament where Rajiv now rarely appears. The Rajya Sabha is now dominated by the party’s lung-brigade: S.S. Ahluwalia, Ratnaker Pandey, Suresh Kalmadi and Jayanthi Natarajan; and the Lok Sabha by the south brigade led by Rangarajan Kumaramangalam, P. Chidambaram; with the west, Vasant Sathe, and Dinesh Singh, close at heel. The formation of various ginger groups of opposition to Rajiv was not entirely unexpected. And they did not take Rajiv by surprise. In anticipation, he had taken a few well-calculated measures. He shrewdly distanced himself from or reassigned to other chores the more discredited members of his several coteries as they had come to be called. Satish Sharma, who had an office at Rajiv’s Race Course Road residence during his prime ministership, is now conspicuous by his absence at 10, Janpath, the opposition leader’s new address. Makhan Lal Fotedar, another permanent fixture in Rajiv’s durbar earlier, is said to have lost much of his clout. He is not regularly seen in the leader’s tow. At least for form’s sake, Rajiv is discussing party matters regularly with senior leaders like P.V. Narasimha Rao, Vasant Sathe and V.N. Gadgil. And old party faithfuls like H.K.L. Bhagat, Balram Jakhar, and C.K. Jaffer Sharief have been resurrected. At his daily morning darshan, Rajiv is assisted by such middle-level leaders as Rameshwar Nikhra, Seva Dal chief, and former minister Margaret Alva. He meets hundreds of ordinary people and grassroots workers. In the Congress (I) office in Parliament he now regularly meets party MPs for an hour everyday. The Congress (I) Parliamentary Party is also meeting every fortnight. This glasnost has already left its impress on some Congressmen, at least. Says AICC(I) spokesman V.N.Gadgil: ‘I see a change in him. He is making an effort to be more accessible to partymen.’ Not everybody in the party, however, is convinced about Rajiv’s new strategy. They point out that during the past five months that the Congress (I) has been out of power, the leadership has failed to reactivate the party. Former party MP Bir Bhadra Pratap Singh gives vent to the prevailing mood in the party: ‘Either he (Rajiv) sheds the former bureaucrats’ ring around him or the party must find a new leader’. Says a senior party leader: ‘Not a single nationwide agitation has been launched, we have just been sitting over issues and opportunities.’ Vasant Sathe repeatedly claims: ‘This young man’s basic political instincts are correct’. But this is probably wishful thinking. For all the cosmetic change and illusion of activity, Rajiv is still a prisoner of various interest groups in the party. In matters of party organization he is being guided by his political aide R.K. Dhawan. Dhawan’s hand is clearly discernible in the recent appointment of party office-bearers both at the national and state levels. While the newly-appointed AICC(I) General Secretary C.K. Jaffer Sharief is known as Dhawan’s protégé, Veerendra Patil and Chenna Reddy, Congress (I) chief ministers of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, have regretted the ‘inadequate representation’ of the south in the latest revamping of the party organization at the national level. Nor has Rajiv forsaken his whimsical style of functioning which marked his five-year rule. The other day he called a meeting of some party functionaries at his residence only after midnight. The partymen were surprised since earlier that day he had no major engagement. And so, disturbing signs are emerging for Rajiv from different party quarters. He is reportedly concerned over the growing ranks of party leaders digusted with his leadership. Madhavrao Scindia, A.R. Antulay, A.B.A. Ghani Khan Choudhary, Dinesh Singh, Hari Krishan Shastri and Ram Chandra Vikal are said to be among them. More ominous, however, was the meeting of the Congress (I) chief ministers of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh at Tirupati recently. Convened ostensibly to discuss the Telugu-Ganga project, the meeting provided the forum for the emergence of what can be called a new syndicate. But Rajiv’s biggest advantage is that a majority of the party’s 107 MPs from the south are reluctant to have anybody else as the party leader. ‘There is no other leader we can sell in our constituency’, says an MP from the south. Adds Bhagat: ‘The nation’s future politics is closely related to what Rajiv Gandhi does during the next few months. There is total unanimity on his leadership in the party’. On the surface, yes. But below it simmers a cauldron of doubt and speculation about who will finally bell the cat and when. Conclusion Dixit’s post-event reminiscence in his memoirs (Assignment Colombo, 1998) was a contribution that could not be ignored. Compared to his 1989 gung-ho view that I had presented earlier, the 1998 version was a mea culpa for his erratic decision making skills. I highlight two facts that Dixit had acknowledged, before presenting my inference. Item 1: “The theory that Rajiv Gandhi insisted on the agreement despite advice against it was wrong. Intelligence agencies, armed forces and the Ministry of External Affairs, including myself told him that the initiatives being taken for signing the agreement were valid and practical. My advice to him was that it was time to bypass the LTTE if they remain obstinate, garner support from other Tamil groups and sign the agreement directly with the Jayewardene Government.” (p. 337) Item 2: “Adhering to absolute principles of morality is the safest and the most non-controversial stance in foreign relations. This, however, is not possible because of the amoral nature of international relations. Safeguarding one’s national interests may result in compulsions which necessitate departure from absolute principles of morality. Once you depart from these principles, to fashion and implement policies to meet your interests, you must have the grit, patience and stamina to follow these policies till they achieve their objectives. If a country, or a people do not have this forbearance and political will, then their policies would remain inadequate and will fail.” (p. 349) What does Dixit euphemistically mentions about ‘amoral nature of international relations’? In reality, Rajiv Gandhi, Dixit and their coteries lied to LTTE leadership and Eelam Tamils to safeguard their “national interests”. Not to mince words, I adhere to the definition of a lie or deceit provided by Prof. Paul Ekman, a respected authority on this theme. According to Ekman, by a lie ‘one person intends to mislead another, doing so deliberately, without prior notification of this purpose, and without having been explicitly asked to do so by the target. There are two primary ways to lie: to conceal and to falsify.’ [see, Telling Lies, Norton & Co, New York, 1992, p. 28]. Rajiv Gandhi and his coterie concealed and falsified truth to LTTE and Tamils. They eventually paid dearly for their folly. ***** |

||

|

|||