Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 3: Emergence of Tamil Consciousnessby T. Sabaratnam, August 12, 2010

Historiography The tradition of writing the history of the people of Northern Sri Lanka is of recent origin. The oldest existing historical work Yazhppana Vaipava Malai compiled by Mailvakana Pulavar appeared in 1736. It depended on earlier writings: Kailaya Malai, Vaiya Padal, Pararasasekaran Ula and Raja Murai. These, composed not earlier than the fourteenth Century A. D., contain folklore; legends and myths mixed with historical anecdotes.

There are references to the people of the Northern Province in the Hindu classics Ramayana and Mahabharata. Some information is available in the Tamil classical literature. Sangam anthologies and the twin epics Silapathikaram and Manimekalai provide some references. Mahavamsa which gives the history of the Sinhalese and Buddhism is silent about the history of the people who lived in other parts of the country. It records only the events connected with the Anuradhapura Kingdom. Yet, it provides some valuable indirect information. Scholars who write the history of the northern and eastern provinces depend mainly on archaeology, anthropology, folk studies and linguistic history. From such studies Jaffna University scholars have concluded that Tamils from Tamil Nadu had migrated to the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka about 3000 years ago and had branched off to the islands off the Jaffna peninsula. They had then moved on to the Jaffna peninsula. Jaffna University studies have identified Poonari and Mannittalai as the points where these Tamils from Tamil Nadu first settled down before moving to Nainativu, Karaitivu and Sambalturai which were ports on the ancient trade routes. Archaeologists believe that the earliest inhabitants of the Jaffna peninsula were Megalithic people who used large-sized stones to construct burial chambers. This culture prevailed during the period 3000 years to 2300 years ago. The people of this period used iron tools and were engaged in agriculture. Development of settlements and urbanization was characteristic of this period. In South India, the rise of earliest kingdoms and chieftaincies took place during this period. Anuradhapura’s emergence as a kingdom also occurred during this time. Northern Sri Lanka also should have undergone this process. Archaeological excavations planned by the Jaffna University may throw light on these matters. Linguistic History Linguistic historical studies have revealed two different processes taking place during this period in the southern and northern parts of Sri Lanka. In the south the process that led to the formation of the Sinhalese language commenced during this era. In the north the Tamil language which was a developed language with rich literature and standardized grammar started absorbing the indigenous languages or dialects. Trade, migration and religion were the factors that influenced these processes. Researchers have so far not found any written evidence to determine the language or dialects used by the indigenous people: Yakkhas and Nagas. Indrapala in his book The Evaluation of Ethnic Identity- The Tamils of Sri Lanka (Page 60) says, “As far as the archaeological evidence is concerned there is nothing to identify the languages or dialects of the EIA (Early Iron Age) people. Written records are not available before the 3rd century BC. Nor are there clearly identified survivals of the early languages through oral traditions.” Ample evidence is now available- archaeological, epigraphic and literary- that Prakrit and Tamil languages entered Sri Lanka in the early years of Early Iron Age, 1000- 300 BC, and had established themselves by the middle of the EIA in different parts of the country. The entry of Prakrit, the spoken language of North India, led to the evolution of the Sinhala Language. Tamil that had established itself as a developed literary medium at least in the 3rd Century BC also entered Sri Lanka during the same period. Researchers have found that Prakrit had begun to affect the indigenous language or dialect from the early years of EIA. It was brought by traders from North India to the trading ports on northwestern coast, particularly Mattoddam and Tambapanni. Prakrit had emerged as the lingua franca of South Asian trade. Its impact had increased by the 3rd Century BC when Buddhism emerged the dominant religion. With the arrival of Prakrit-speaking Buddhist priests during and after the introduction of Buddhism Prakrit earned a preeminent position. The earliest stone inscriptions found in Sri Lanka belong to the 2nd Century BC, and all of them are in Prakrit, exhibiting traces of Dravidian language influence. The evolutionary process of the new language was slow because Pali, the language of Buddhism, received the backing and recognition of the Buddhist Sangha and the royalty. Pali though a dead language took precedence over the evolving new language, Hela, and all major literary works were written in that language. It took some time for the monks to get bold enough to write commentaries to the Pali texts in Hela, the language the people understood. This happened during the closing years of the EIA, which were around 300 BC. None of the commentaries or other literary work written during the EIA period have survived. Researchers agree that Hela of the EIA period is the older form of the Sinhala language. Historical linguists who work on the origin and development of the Sinhala language have agreed that the formation of Hela which progressed slowly gathered momentum with the arrival of North Indian Buddhist monks and Prakrit earned a position of respectability. Elite gave their children Prakrit names and Prakrit-derived Hela began to evolve into an independent language, Sinhala. The Sinhala language reached the literary stage by the 8th Century AD. While Prakrit gained dominance and the Sinhala language began to evolve in the southern part of Sri Lanka a different process took place in the northern part of the island. There, Tamil had become the dominant language, and began to replace the languages spoken by the indigenous people, the Nagas. Tamil had established itself as the dominant language in Tamil Nadu well before the 2nd Century BC and thus during the EIA period it had begun the process of assimilating and integrating other languages and dialects. Pandyan chieftaincy provided the lead needed for that to occur. Madurai, the Pandyan capital, according to archeologists, was one of the earliest urban centers in India and the earliest in South India. The original city which stood at the mouth of Vaikai was destroyed by a deluge but was rebuilt and named Kapatapuram, which too suffered the same fate. Pandyans built the city again upstream and named it Madurai. Tamil literature calls it Then Madurai (Southern Madurai) and in Pali it was referred to as Dakkhina Madurai. Mahawamsa calls it as Dakkhninam Madurai. Early Iron Age inscriptions discovered in Tamil Nadu belong to the 2nd Century BC and were in old Tamil but showed the influence of Prakrit. A similar trend was found in coins too. During mid- EIA period- about the 5th Century BC- Tamil had emerged the dominant language in Tamil Nadu. The emergence of Tamil as a developed literary medium was reflected by the Sangam poetry. Researchers date the earliest of the Sangam poems to about the 2nd Century BC. Allowing three centuries for Tamil to develop to that position, linguists assert that Tamil should have emerged to the position of the dominant language of Tamil Nadu by about the 5th Century BC. Tamil attained that position in Tamil Nadu despite the onslaught of Prakrit. Prakrit speaking north Indian traders were very active in South India during mid-EIA period. Prakrit-speaking Buddhist and Jain monks crossed into South India during the fourth Century BC. Earliest inscriptions in South India reveal that the impact of Prakrit was greater in Andhra, Karnataka and Northern Tamil Nadu (Pallava territory) than in Southern Tamil Nadu. In Southern Tamil Nadu almost all the inscriptions are in Old Tamil. Prakrit failed to gain ascendancy in the southern Tamil Nadu because Tamil was well entrenched and could not be dislodged. It also could not be Sanskritized like the other South Indian languages- Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. Scholars have estimated that Tamil had attained this dominant position in Tamil Nadu during the very period EIA culture was crossing over to Sri Lanka. Indrapala says that Tamil would have crossed over to the Sri Lankan Northwestern coast in several ways. He says that it would have been carried by: the traders who frequented the Pandyan port of Kotkai and Sri Lankan port of Mattoddam; the people of the Vaikai valley who migrated to the northwestern coast; the Tamil Nadu fishermen involved in the pearl and chank [1] fisheries. No definite information is available about when the Tamil language started to cross over to Sri Lanka. But there is definite archaeological evidence that showz cultural interaction between Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka from prehistoric times. The crossing and spread of Tamil into northern Sri Lanka was swift because the Naga tribe lived in both Tamil Nadu and Northern Sri Lanka. Jaffna Principality Archaeological excavations done in Vadamarachchi East have brought to light the existence of ancient human settlements in the area. Archaeology Director General of Sri Lanka, Dr. Senarath Dissanayake announced in February 2010. "We have found evidence of three old human settlements in these areas. They have spread over an area covering nearly three kilometres and are vitally important to prove the historical background of Jaffna peninsula." Kandarodai was the fist site the Archaeology Department excavated in the Jaffna peninsula. It was conducted in 1918 by a team headed by Sir Paul E. Pieris. They discovered punch-marked coins called puranas that was current in India during the 6th and 5th centuries BC . Sir Paul E. Pieris concluded from those discoveries that Kantarodai was a flourishing settlement even before the arrival of Vijaya. Subsequent excavations carried out in 1956 and during 1980 and 1983 showed the existence of ancient settlements at Pomparippu in the Puttalam district, Poonari in the Kilinochchi district, in the islands off the Jaffna peninsula and in several parts of the peninsula. Most of them resemble the settlements discovered in Tamil Nadu. From these discoveries scholars have concluded that there were migrations from the southern coast of India to the northern coastal areas of Sri Lanka. In this context the statement of Sir Paul E. Peiris becomes relevant. He said, "It stands to reason that a country which is only 30 miles from India and which would have been seen by Indian fishermen every morning as they sailed out to catch their fish, would have been occupied as soon as the Continent was peopled by men who understood how to sail." Tamils could have migrated to the northern part of Sri Lanka not only as fishermen and pearl drivers but also as traders, seamen, soldiers, artisans or refugees fleeing from political upheavals in their motherland. It was a process that occurred over centuries. Pottery and a seal found at Anaikoddai and other material found at Kalapumi, Karainagar and Kantarodai establish beyond doubt that there were permanent settlements in the Jaffna Peninsula - at least in the third century BC. if not earlier. The Brahmi scripts, found at Anaikoddai and Kantarodai, assigned to third century B.C., occur along with what could be assumed to be a previous system of writing. This suggests that the Megalithic culture arrived in Jaffna long before the Christian era and caused the emergence of rudimentary settlements and continued into the early historic times marked by urbanization. The process of urbanization was promoted by the trans-oceanic trade that developed around the beginning of the Christian era. Northern ports emerged a link in the South Asian and transoceanic maritime trade. Roman and Indian ships used the Palk Strait to travel between the western and eastern coasts of India. Mattoddam, Karainagar and Sambalturai emerged as important trading centers. Jaffna developed as an urban settlement center and Kantarodai emerged as its central place. Ponnampalam Ragupathy of Jaffna University says in his paper Tamil Social Formation in Sri Lanka that the development of Jaffna as a principality occurred parallel to the development of the urbanized centers in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu: Anuradhapura, Mahagama, Korkai, Kaviripattinam and Arikamedu. Buddhism in Jaffna Jaffna principality flourished till the decline of the Roman trade in the 5th Century AD. Buddhism became the religion of the people of Jaffna during this phase. As pointed out in the last chapter Tamil Nadu was under the rule of Kalabhras and Buddhism and Jainism took deep root there. Jaffna was influenced by that development. People of Jaffna adopted Buddhism in preference to Jainism because Buddhist influence was already present in Jaffna since the time of Devanampiyatissa. As pointed out in the last chapter Jaffna principality was under the Anuradhapura Kingdom during the period of the first Lambakanna dynasty, 67 AD- 428 AD. It only meant that Jaffna chieftain accepted the King of Anuradhapura as his overlord and paid him tribute. He carried on his administration in the traditional way and Tamil was the language of administration. Scholars say that Jaffna chieftains did not pay the tribute and acted independently whenever the the ruler of Anuradhapura was weak. According to Mahavamsa only three kings built or renovated Buddhist shrines in the Jaffna peninsula during this period. Mahallakanaga, the fourth king, built the Salipapatha Vihara, Kanittha Tissa, the sixth king renovated a shrine and Yoharikka Tissa, the tenth king constructed a wall around Tissa Vihara.

Tamil researchers say that the archaeological evidence discovered in Kantarodai should be viewed in this context rather than in the context of the events in Anuradhapura. A cluster of 22 dagabas, the head of a Buddha statue, pillar stumps and a footprint stone were among the items discovered. Remains of the site of a large monastery has also been discovered. Kantaroda is on the Chunnakam- Manipai road, two kilometers from Chunnakam. Diameter of the base of the dagobas range from three to four meters. The base of the biggest dagoba has a diameter of about seven meters. They were constructed with coral and lime stones and are different from the dagobas in Southern Sri Lanka in the concept of architecture and execution. The materials used for construction were also different. Dr. Senarath Dissanayake commenting on the discovery of the monastery said it belonged to the Iron Age and added “there are sufficient evidence to suggest that these human settlements of Kantarodai lead to the existence of a very old history in the peninsula”. Buddhism and Jainism disappeared from Tamil Nadu with the decline of the Kalabharas in the early part of the 5th Century. The traditional Tamil kingdoms, Pandyas, Cholas and Cheras, then reasserted their power. In Tamil Nadu history the period beginning from the 6th Century AD is described as the era of empires. It is also called the age of Saiva revivalism. Jaffna people who usually adopted the developments in Tamil Nadu also returned to their original faith of Saivaism, the worship of Siva. Buddhism practiced in Tamil Nadu and Jaffna was Mahayana Buddhism and not Theravada Buddhism which was predominant among the Sinhalese. Mahayana Buddhism which was preached from the prestigious seats of Buddhist learning, Nagarjunakonda in Andhra and Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu was despised by Mahavihara, the citadel and guardian of Theravada Buddhism, as a corrupted form of Buddhism and deridingly called Tamil Buddhism because it was preached in Tamil. Mahayana posed a threat to Theravada during the period Jaffna was under Buddhism. The threat from the Mahayana sect was prevalent throughout the period it was practiced in Jaffna. According to Mahavamsa Mahavihara monks rose against the upsurge of Mahayana influence and persuaded the king, Voharika Tissa (209 AD-231AD) to take measures to suppress its teaching. The situation changed under Mahasena (274AD-301AD) who patronized Mahayana Buddhism. The influence of Mahayana Buddhism did not last long and Theravada returned to its dominant position soon. Since the middle of the 6th Century Jaffna remained predominantly Saivaite till Portuguese introduced Roman Catholicism in the 17th Century. The only instances of Buddhist intrusion recorded during this period was: King Aggabodhi II (604 AD-614 AD) converting the Unalomaha temple in Jaffna into Rajayathanathathu Vihara and donating an umbrella to the Amalathesia Chaitiya. Saiva Revival The revival of Saivaism and the emergence of Lambakanna II dynasty in 691 AD which took measures to curb the influence Tamils wielded in the affairs of the royal court in Anuradhapura were the main factors that promoted the emergence of Tamil consciousness among the people of the north. Saiva revival began in Tamil Nadu following the defeat of Kalabhras by the Pandyans and Pallavas in 550 AD. It also saw the revival of Vaishnavism (worshipers of Vishnu). Saiva revival peaked in the latter part of the 7th Century.

The revival was stimulated by Saiva Nayanmars and Vaishnava Alvars (saints). That period produced the Bakthi cult (Devotional cult) and Karaikkal Ammaiyar who lived in the 6th Century AD was the earliest of these Nayanmars. The celebrated Saiva hymnists (Thevaram) Sundaramurthi, Thirugnana Sambanthar and Thirunavukkarasar were of this period. Saiva Nayanmars and Vaishnava Alvars provided the stimulus to this revival. Following this revival Saivaism and Vaishnavism became dominant, replacing Jainism and Buddhism. This change impacted on literature, art, and architecture of the entire Tamil Nadu. Some of the earliest temples were built during this period by the Pallavas. The rock-cut temples in Mamallapuram and the majestic Kailasanatha and Vaikuntaperumal temples of Kanchipuram stand testament to the Pallava art. The Cholas, utilizing their prodigious wealth earned through their extensive conquests, built long-lasting stone temples including the great Brihhadisvara temple of Thanjavur and exquisite bronze sculptures. This revival had a great impact on the northern Tamils and Saivaism became the rallying point for their new vocalism. While the Tamils were feeling the impact of the religious revival taking place in Tamil Nadu Manavamma who established the rule of the Lambakanna II dynasty took steps to reduce the influence and powers of the Tamil army commanders and courtiers. He removed many from the high positions they held and established a strict supervision over their activities. His successors tried to continue his policy of reducing Tamil influence over the affairs of the state but were less successful because they could not do without them.

The disgruntled Tamil commanders either returned to Tamil Nadu or moved to the north with their families. They joined the Tamil chieftains of Vanni and Jaffna and fuelled rebellion. The Chulavamsa, the Pali chronicle that records Sri Lankan history from the sixth century onwards, speaks of a rebellion by the local administrators of the north during King Mahinda II's reign (777AD-797 AD).The revolt was led by Ukkira Singhan. Ukkira Singhan who led the revolt, according to Yalpana Vaipava Malai was a North Indian prince who came to Sri Lanka with an army in 785 AD when Mahinda II was ruling Polonnaruwa and tried to conquer it. Failing in his attempt he marched to the north and captured the Jaffna principality. He changed his capital from Kantarodai to Singhai Nagar which historians say was in Poonari. Tamil Invasions Narasinghan, Ukkirasinghan’s son, succeeded him. He assumed the name Jayathunga Pararajasingham when he was crowned. The Pandyan invasion took place during his time. The Pandyan Kingdom had expanded rapidly after the overthrow of the Kalabhras in 550 AD. Pandyan King Sri Mara Sri Vallabha (815- 860 AD) who landed with a large army in the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka captured Anuradhapura defeating Sena I (833- 853 AD). He then captured Singhai Nagar and made Jayatunga accept him as his overlord and made him to pay tribute and returned to his country. Fortune changed during the reign of Sena II (853- 887 AD), nephew and successor of Sena I. The Pandyan Prince Varaguna who had fallen out with his father Sri Vallabha wanted to oust him. He obtained the assistance of Sena II and Pallava King Nrpatunga to do it. Anuradhapura army under the commander Kutthaka laid siege of Madurai and sacked it after defeating the Pandyan army. He sacked Madurai, recovered some of the loot taken by Sri Vallabha from Anuradhapura and took additional treasures. Varaguna was crowned king of Pandi Nadu in 862 AD in which Kutthaka participated as Sena II’s representative. This Pandya- Anuradhapura friendship did not last long. Around 850 AD Vijayalaya, an obscure Chola prince, making use of the conflict between Pandyas and Pallavas, captured Tanjavur and eventually established the imperial line of the medieval Cholas. Vijayalaya revived the Chola dynasty and his son Aditya I helped establish their independence. He invaded the Pallava kingdom in 903 AD and killed the Pallava king Aparajita in battle, ending the Pallava reign. The Chola kingdom under Paranthaka I (907- 955) expanded to cover the entire Pandya country. Paranthaka II (955- 973 AD) defeated the combined army of Pandyan King Rajasimha II and Anuradhapura ruler Dappala IV and Rajasimha II fled to Anuradhapura with the Pandyan crown. Dappala IV welcomed Rajasinha II despite objections from his ministers and generals. They feared the wrath of the Cholas. Realizing the difficulty of Dappala IV, Rajasingha II went to Chera Kingdom leaving the crown in the custody of Dappala IV. Paranthaka II demanded the crown after he completed his conquests to enable him to be crowned the king of the Pandyan kingdom in addition to his own. Udaya IV refused to give it and Paranthaka I sent his army to recover it. The army landed in Karainagar and marched to Anuradhapura, capturing and pillaging the city. Udaya IV fled to Ruhuna. Paranthaka I then withdrew his army from Sri Lanka because his kingdom was attacked by Rashtrakutas from the north. The Cholas went into a temporary decline during the next few years due to weak kings, palace intrigues and succession disputes. Despite a number of attempts, the Pandya country could not be completely subdued and the Rashtrakutas were still a powerful enemy in the north.

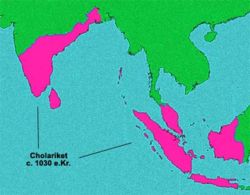

Chola revival began with the accession of Rajaraja Chola I (985-1012 AD). Cholas rose as a notable military, economic and cultural power in Asia under Rajaraja and his son Rajendra Chola I. The Chola territories stretched from the islands of Maldives in the south to the banks of the river Ganges in Bengal in the north. Rajaraja Chola conquered peninsular South India, annexed parts of Sri Lanka and occupied the islands of Maldives. Rajaraja I who was a great soldier and a statesman of vision realized the strategic importance of Sri Lanka and decided to annex it to his empire. He also recognized that Sri Lanka’s ports would increase the strength of Chola sea- power and foreign trade. He found the reigning king Mahinda V was incompetent and that the country was in disarray and decided to seize that opportunity and invaded Sri Lanka in 993 AD. He landed his army at Karainagar as Paranthaka II had and with the help of Tamil chieftains there, he marched straight to Anuradhapura. He conquered the territory ruled by the Anuradhapura king and made it the eighth province of the Chola empire which was then called ‘Mummudichola mandalam’, meaning that the Chola king wore the crowns of Cholas, Pandyas and Cheras, the traditional three kingdoms of Tamil Nadu. Mahinda V fled to Ruhuna with the crown and Rajaraja I did not pursue him, as he was content with the northern part of the country that included the Trincomalee harbour. Rajendra I (1012- 1044 AD) who concentrated on developing trade with Malaya and China realized that he had to conquer the entire island to be able to have full control over the eastern ports. In 1017 AD he brought the entire country under his control by capturing Mahinda V, his queen and the crown. He transferred the capital to Polonnaruwa and renamed it Janathamangalam. Thus, the long history of Anuradhapura came to an end. Rajendra Chola extended the Chola conquests to the Malayan archipelago by defeating the Sri Vijaya kingdom and extended his kingdom up to the bank of Ganges by annexing the kingdoms of Bihar and Bengal. To commemorate his victory he built a new capital called Gangaikonda Cholapuram. At its peak, the Chola Empire extended from Sri Lanka in the south to the Godavari basin in the north. The kingdoms along the east coast of India up to the river Ganges acknowledged Chola suzerainty. Chola armies exacted tribute from Thailand and the Khmer kingdom of Cambodia. Rajathiraja, Rajendra II and Virarajendra I, in turn, succeeded Rajendra I. They were his sons and they continued his policies.

A knowledge of the period of the rise of the Chola empire is essential to understand the emergence of Tamil consciousness, the environment that led to the founding of the Tamil state and most importantly the factor that prompted Pirapaharan to launch the armed phase of the Sri Lankan Tamil struggle. The slogan that motivated the Tamil struggle was based on the achievements of the Cholas. ‘Aanda InamAdimai Paduwatha? (meaning Should the race that ruled become slaves?) It was coined by Amirthalingam. Cholas were constantly troubled by the Sinhalese during this period. They were trying to eject them from Sri Lankan soil. Cholas were also harassed by the Pandyan princes who were trying to liberate their traditional territories, and by the Chalukyas. The history of this period was one of constant warfare between the Cholas and these antagonists. Added to that was the travail of internal disputes and the passage of power to the Chalukya Chola dynasty. Virarajendra Chola's son Athirajendra Chola was assassinated in a civil disturbance in 1070 and Kulothunga Chola I ascended the throne. Kulothunga was a son of the Vengi king Rajaraja Narendra and Chalukya Chola dynasty came to power. The decline of the Chola power commenced during this period. The Cholas lost control of Lanka and were driven out by the revival of Sinhala power. After the Chola invasion Tamil influence increased in Sri Lanka. It took root in Sri Lankan politics, society and culture. Immigration of Tamils into Sri Lanka increased greatly. A large number of officials, soldiers, merchants and artisans came and settled in Sri Lanka. Several Hindu temples were built and Saivism in its most developed form was introduced. Chola influence on administration, architecture and coinage were considerable. Tamil became the language of official records and it retained that position until the advent of colonial rule. Tamil mercantile communities began to play a major role in the internal and external trade. K.M. De Silva observed that, ‘the inevitable result of the Cola conquest was the Hindu- Brahmanical and Saiva religious practices, Dravidian Art and Architecture and the Tamil language itself became overwhelmingly powerful in their intrusive impact on the religion and culture of Sri Lanka.' Environment for a Tamil State Resistance to the Chola rule began in Sri Lanka a few years after Rajendra Chola’s conquest of the whole island. Ruhuna emerged the centre of the resistance movement. There was opposition to them from Rajarata also. The Sinhala resistance was led by young Prince Kirti who was asked by the Sinhala leaders in around 1050 AD to head the movement to oust the Cholas from Sri Lanka. He organized a campaign and after careful preparation attacked the Cholas in two fronts- Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. Virarajendra (1063-1069 AD) sent an expedition to tackle the situation which defended the Chola-held territory. The situation turned against the Cholas with the death of Virarajendra, the assassination of his successor Athirajendra Chola and the appointment of Kulotunga Chola I. Kulotunga did not evince any interest in retaining Sri Lanka. Realizing this Kirti intensified his attack and Cholas were pushed out of Sri Lanka in 1070. Kirti ascended the throne as Vijayabahu I (1055 AD-1110 AD). The Cholas brought Jaffna under the control of their representative at Polonnaruwa who made use of Bhuvanekabahu who was ruling Singhai Nagar as his governor. Mootootamby Pillai, author of ‘Jaffna History’ says Bhuvanekabahu was the title given to Neelakandu Iyer from Pandi Nadu who served as the minister under Jayatunga. It seems that he succeeded Jayatunga who had no children as the ruler of Singhai Nagar. Vijayabahu I proved himself a good administrator. He united the country. He brought Jaffna again under Sinhala rule. But for 53 years from the death of Vijayabahu I in 1110 AD to the coronation of Parakramabahu I (1153 AD-1186 AD) in 1153 Polonnaruwa was weakened due to succession disputes and weak rulers. Making use of this opportunity the provinces and principalities in the south went their own way and the north also followed suit. But when Parakramabahu I established his rule Sinhala dominance was reestablished. Stone inscriptions found in Nagadeepa and Thiruvalankadu in Tamil Nadu indicate that Parakramabahu I ruled the Jaffna peninsula, The Nagadeepa inscription indicates that sea commerce at Karainagar was under Parakramabahu I and Thiruvalankadu inscription states that his navy was stationed at Karainagar, Mattivil and Valikamam. Mootootamby Pillai calls Parakramabahu I a benevolent ruler who respected Saivaism. According to Mootootamby Pillai the Jaffna ruler Bhuvanekabahu accompanied Parakramabahu I when he toured the north. Parakramabahu I’s reign is fondly remembered by the Sinhalese people. It was a period of frenetic activity and great achievements. He maintained a good relationship with the Buddhist Sangha and the Hindu fraternity. Parakramabahu I was the last of the great rulers of ancient Sri Lanka. Parakramabahu I did not have any sons and Vijayabahu II, the senior of the claimants, was allowed to rule until the dispute about the successor was settled. Nissanka Malla, (1187 AD- 1196 AD),a Kalinga Prince, during his nine-year rule, managed to continue the good work done by Vijayabahu I and Parakramabahu I but their successors failed to live up to their achievements. After Nissanka Malla died in 1196 AD six men and two women ruled Polonnaruwa in the short period of 16 years before the Pandyan Prince Parakrama Pandu seized the throne in 1112 AD. The prosperity achieved by Polonnaruwa during the reign of the earlier rulers and the mess and weakness created by the later rulers attracted the attention of the powerful Tamil kingdoms of Pandi Nadu and Chola Nadu. But Chola power was on the decline during that time and Pandyas were growing strong. The Pandyan prince Parakrama Pandu who seized Polonnaruwa by defeating Lilavathi in 1212 AD ruled for three years. Parakrama Pandu was defeated in 1215 AD by Kalinga Magha who was also called Kalinga Vijayabahu (1215AD-1236 AD) who ruled for 21 years. Magha is said to have landed in Karainagar in 1215 AD with a huge army of 24,000 soldiers recruited in the Chola and Pandyan kingdoms, stayed in Karainagar and Valikamam and brought the Jaffna peninsula and the chieftaincies in Vanni under his control. He consolidated his position there, appointed a governor and marched on to Polonnaruwa. The Southward Shift Magha’s conquest of Polonnaruwa forced the Sinhalese kings to shift their capital to Dambadeniya and the emergence of a Tamil state in the north made the Sinhalese move further and further south. They went in search of secure rocks to establish their capital, a measure to ward off South Indian and Tamil attacks. In 1273 AD Bhuvanekabahu, I established Dambadeniya as his capital and a few years later moved to Yapahuva. In 1302 AD Bhuvanekabahu II shifted his capital to Kurunegala and in 1341 Bhuvanekabahu IV moved the capital to Gampola. Dedigama was also used as an alternative by him and his successor Parakramabahu V. Bhuvanekabahu V moved on to Kotte. On two occasions during the early part of this period, unsuccessful attempts were made to return to Polonnaruwa. Vijayabahu IV (1272- 1274 AD) attempted to restore Polonnaruwa as his capital. That attempt failed because he was assassinated by his general, who assumed the crown. His younger brother, Bhuvaneka Bahu I succeeded in escaping and was crowned in 1271 after the usurper was murdered. Early in his reign he had to deal with a Pandyan invasion, which he repelled; thereafter he lived for a few years at Dambadeniya, and then moved to Yapahuva. After Bhuvanekabahu I there was an interregnum of two years before Parakramabahu III succeeded him to the throne. The Chulavamsa relates that after Bhuvanekabahu I's death in 1284 AD, there was a famine and the Pandyan king Kulasekara (1268-1308 AD) sent his minister Ariyachakravarti to invade Sri Lanka. Ariyachakravarti who is mentioned in a Pandyan inscription of 1305 AD, succeeded in capturing Yapahuva, and in carrying off the Tooth Relic. The interregnum might be due to the Pandyan invasion. Parakramabahu III 1287 AD- 1293AD) went to Pandyan court, offered himself to be a tribute-paying fiduciary, and brought back the Tooth Relic and kept it at Polonnaruwa where he ruled. His cousin Bhuvanekabahu II (1293- 1302 AD), who was in Kurunegala defeated Parakramabahu III and seized the Tooth Relic and took it to Kurunegala in 1293 AD. Parakramabahu III was the last Sinhala king to rule from Polonnaruwa. After him, no Sinhala king exhibited the aspiration to return to Polonnaruwa. The foundation for the Second Pandyan empire was laid by Maravarman Sundara Pandyan in 1216 AD. Pandyan glory was briefly revived by Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan (1251- 1268 AD), the fourth ruler of the dynasty. The Pandya power extended during his time from the Telugu countries on the banks of the Godavari river, to the northern half of Sri Lanka, Marco Polo notes that the Pandyan kingdom though the richest in the world, and very prosperous did not possess the proportionate military strength. On the death of Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I (1268 AD – 1310AD), the successor of Jatavarman, a conflict stemming from succession arose amongst his sons. Kulasekara Pandyan had two sons; Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan and Jatavarman Veera Pandyan. The elder son, Sundara Pandyan, was by the king's wife and the younger, Veera Pandyan, was by a mistress. Contrary to tradition, the king proclaimed that the younger son would succeed him. This enraged Sundara Pandyan. He killed the father and seized the throne in 1310. Some local chieftains in the kingdom swore allegiance to the younger brother Veera Pandyan and a civil war erupted. Sundara Pandyan was defeated and he fled the country. He sought help from the northern ruler Sultan Ala-ud-din Khiljiwho was ruling much of northern India from Delhi. At that time, his army under General Malik Kafur was in the south at Dvarasamudra (north of Tamil Nadu). Khilji agreed to help Sundara Pandyan and ordered Malik Kafur's army to march to Tamil Nadu. With Sundara Pandyan's assistance, the Muslim army entered Tamil Nadu in April 1311. Then Malik Kafur turned against Sundara Pandyan who fled Madurai to southern Pandya Nadu. Malik Kafur looted Madurai and returned to Delhi. Subsequently other Muslim Sultans raided Madurai and the Pandyan Kingdom came under the Delhi Empire in 1323 and was ruled by Tughlaks. That ended forever the existence of Tamil states in Tamil Nadu, the territory that had three Tamil states, Chera, Chola and Pandya, from the beginning of history. But with Tamil Nadu losing its sovereignty and becoming a tribute-paying satellite to a North Indian Muslim state in Delhi the rising Jaffna Kingdom that was under Pandyan suzerainty since its inception in 1215 declared itself independent and emerged as the only Tamil state in the globe. Varothayar, the fifth ruler of the Jaffna Kingdom made the independence declaration. Incidentally, Jaffna Kingdom was the last independent Tamil state of the world. (Next Friday: Birth of the Tamil State) 1. Chank = the East Indian name for the large spiral shell of several species of sea conch much used in making bangles ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ DiscussionAuthor’s Note I am pleased that my account of the context that created the ethnic conflict in our motherland had generated a healthy discussion. I took up journalism when Tamils believed in a negotiated settlement. I reported that phase from 1957 to 1983. During the latter part of that phase- beginning from 1970- I reported on the emergence and growth of the armed movement. I also reported on the gradual ousting of the democratic Tamil Leadership by the armed groups. The process was assisted by President J.R. Jayewardene and later by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Are you surprised? Wait patiently and read my account. Please remember this: The Sri Lankan history we studied and is being taught is a Sinhala biased account. Tamil historians have researched and written their side of the history. As I mentioned in my introduction I am highlighting their findings in my account. I am reproducing below the concluding portion of my introduction:

I have decided not to take part in the discussion. You are free to have your say subject to the policy followed by the Editorial Board of Ilangai Tamil Sangam. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Index Emergence of Racial Consciousness |

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||