Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 4: Birth of a Tamil stateby T. Sabaratnam, April 18, 2010

Birth A Tamil state was born in Sri Lanka 1465 years after the birth of the Sinhala state. The Sinhala state was founded by Devanampiyatissa in 250 BC and the Tamil state in 1215 AD. Historians ascribe its founding to Kalinga Magha.

Kalinga Magha was a prince from the Kingdom of Kalinga which was in the Orissa state of modern India. His family was connected to the rulers of Ramanathapuram in Tamil Nadu. Kalinga Magha’s relatives of Ramanathapuram administered the famous temple of Rameswaram. Kalinga Magha landed in Karainagar in 1215 AD with a large army of 24,000 soldiers mostly recruited from Chola and Pandyan territories. He camped his soldiers in Karainagar and Vallipuram and brought the Jaffna principality and the chieftaincies in Vanni under his control. Historian Rev. Fr. Gnapragasar in his book Yalpana Vaipava Vimarsanam says that Kalinga Magha took the name Segarajasekeran Singhai Ariyachakravarthi on coronation. He said his descendents too adopted the title Singhai Ariyachakravarthi. Rasanayagam, author of Ancient Jaffna, to Indrapala have accepted that view. Kalinga Magha consolidated his position by organizing the territory as a Hindu- Tamil chieftaincy and accorded encouragement to Hinduism and Tamil. He built the new capital Nallur and made it the seat of his government. He built Hindu temples and provided them with resources. He denied Buddhists the support they had enjoyed under the Sinhala monarchs. That prompted majority of the Sinhala settlers at Kantarodai and Vallipuram to move southwards. Kalinga Magha then marched to Polonnaruwa after appointing Jayabahu as the governor for the Jaffna kingdom, defeated Parakramabahu and ruled it for 21 years. He was expelled from Polonnaruwa in 1236 and withdrew to Jaffna which he ruled till 1255. During his rule he laid the foundation for a powerful Tamil state. He introduced an administrative system based on that prevalent in Kalinga. He divided the Jaffna peninsula into four regions and appointed an adikari (chief administrator) for each of them. He also appointed adikaris for the islands and Vanni. They functioned as his agents looking after the administration, taxation, welfare, development and justice. They were assisted by mudaliyars, who were placed in charge of the villages and settlements. Mudaliyars were in charge of justice; they settled disputes and punished the offenders. Under mudaliyars functioned pandarapilai, kankani, udayar, thalaivari and other minor officials. Kulasekaran Ariyachakravarthi, the third king of the Jaffna dynasty refined the administrative system. The administrative system introduced by Kalinga Magha is the basis of the prevailing administrative system in Jaffna. Kalinga Magha also paid special attention to external trade and defence. Pearls, chanks and elephants were the main items of export during his period. He paid special attention to pearl fishery. Pearl fishing was done in April and May and king’s officials camped in that area and collected half of the income from the fishermen. He also commenced the process of the expansion of the Jaffna Kingdom by bringing the territory north of Mannar and Trincomalee under his control and turning that into a separate unit. He placed that unit under the direct control of Jayabahu. Kalinga Magha paid special attention to maintaining an army because he feared attack from the resurgent Polonnaruwa kingdom. He also built a navy mainly to safeguard the northern trade routes. Java king Chandrabhanu invaded the Jaffna kingdom in 1255, defeated Kalinga Magha and ascended the throne as the second king of the Jaffna dynasty. He attacked Dambadeniya in 1258 AD which was ruled by Parakramabahu II (1236-1270 AD) but was repelled with the help of Pandyans who had developed a cordial relationship with him (Parakramabahu II). Pandyans allowed Chandrabhanu to continue his rule of the Jaffna Kingdom as he agreed to be a tributary to them. Chandrabhanu did not give up his ambition to capture and rule the entire island. He recruited an army from Pandya Nadu and Chola Nadu and attacked Dambadeniya a second time. Parakramabahu II appealed to the Pandyan monarch for help. The Pandyan king Virapandya invaded Jaffna, defeated Chandrabhanu and raised his son Tambralinga to the throne. He did so because he did not want to give Jaffna to the Sinhala king. Tambralinga followed the example of his father and attacked Dambadeniya. The Pandyan King sent an army headed by his general Kulasekaran who defeated Tambralinga 1262. Again, the Pandyan king decided not to hand Jaffna to the Sinhalese and installed Kulasekaran as the King of Jaffna. The seven years the Java kings ruled are taken together and Chandrabhanu is considered the second king of the Jaffna dynasty. Kulasekaran took the throne name Pararajasekeran and the title Ariyachakravarthi. He was the third king of the Jaffna dynasty. He ruled from 1262 to 1284. He was succeeded by his son Kulothungan Singhai Ariyachakravarthi. He took the throne name Segarajasekeran, the throne name of Kalinga Magha. He ruled for eight years, 1282- 1292. He repelled an invasion by Yapahuva king Bhuvanekabahu who tried to seize the pearl fishery in Mannar.

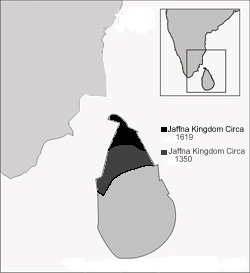

His son Vikrama succeeded him and ruled under the throne name Pararajasekeran II. He ruled for ten years, 1292-1302. Vickrama put down with a strong hand a riot by the Sinhalese living in Jaffna. Sinhalese rioted because they had lost the support they had received during the time Sinhala kings ruled the north. Vickrama arrested the leaders who fomented the disturbance, Punchi Banda and 16 others, and beheaded them, He jailed many others. The credit for building strong institutions for the Tamil people should go to the first five rulers of the Jaffna Kingdom – Kalinga Magha, Chandrabhanu, Kulasekaran, Kulothungan and Vikrama – who ruled for the first 87 years, 1215-1302. During this period, they consolidated their regime by repelling invaders, quelling rebellions and controlling troublemakers; brought in stability and economic advancement by creating settlements and promoting agriculture, built a strong administrative and military base and created wealth through foreign trade. They also promoted Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism by encouraging religion, literature and culture. Parallel to the emergence of the Kingdom of Jaffna independent chieftaincies, known as Vanniyars, emerged in the territory between the Sinhala and Tamil kingdoms. Most important of them were the chieftaincies of Vanni, Trincomalee and Batticaloa. The chieftaincy of Vanni was the most powerful and it continued to exist until 1802 AD when its ruler Bandara Vanniyan was captured by the British. Migration As pointed out in the section on ‘Human Settlements’ in Chapter 1 archaeological evidence reveals that settlements existed in the Jaffna peninsula during the Early Iron Age. Indrapala, Prof. K. Pushparatnam (Head of the Department of History and Archaeology, Jaffna University) and Ragupathy (Lecturer, Jaffna University) have established that they belonged to the megalithic culture, which is undoubtedly a South Indian phenomenon of Iron Age. Says Ragupathy, “Emerging in around 500 BC, the first settlers had a multifaceted subsistence of incipient farming, lagoon exploitation and cattle herding. They communicated in a language that can be termed proto-Dravidian, were non-Buddhists practicing a folk religion similar to that of the Sangam Tamil country and on the whole, were of a common stock of the protohistoric South India.” Earliest Brahmi inscriptions dateable from 3rd Century BC, numbering over one thousand found scattered in most parts of the Dry Zone, provide concrete archaeological evidence for early Tamil settlements. They were found in two layers. The earlier layer, scholars maintain, has forms similar to that which were designated Tamil- Brahmi. Excavations at Anuradhapura and Akurugoda have shown the presence of typical Tamil Brahmi form. Use of early Brahmi in Northern Sri Lanka is also evident from the presence of Brahmi script on potsherds discovered at various places in the Poonari region and Kantarodai. The seal from Anaikoddai, with the title Koveta, Kovetam, datable to 3rd Century BC is again proof for the use of Brahmi in Northern Sri Lanka. Thus, it is evident that the people of South India and northern Sri Lanka adopted a common script during Pre- Buddhist days. The antiquity of the Tamils in Sri Lanka is also borne out by the fact that some words of the Sangam period are still in common use among the peasantry of Jaffna such as aitu, atar, utu, uvan, vantare, which have fallen into disuse in Tamil Nadu. Endearing expressions used in addressing children Mahan (son), Mahale (daughter) mentioned in Tolkapiyam (the earliest Tamil grammar) are still in use in Jaffna. A Tamil poet from Sri Lanka, Ilattuputhanthevanar, adorned the Tamil Sangam of Madurai. Seven of his poems are included in the Sangam Anthologies, Akananuu, Kuruntogai and Nattinai. He may perhaps have lived in the first century BC, as he appears to be one of the earlier poets of the Sangam Age. Tamil settlements sprang up in and around Anuradhapura during fifth to eighth centuries when Sinhala rulers brought Tamil mercenaries to fight on their behalf. And during the latter part of this period when the north was used as the staging post for attacks on Anuradhapura Tamil settlements in Jaffna increased. Prof. P.A.T. Gunasinghe of Peradeniya University has highlighted the significance of this development regarding the formation of the Tamil state and the growth of Tamil settlements in the north. He said, “From the 7th century onwards, there gradually developed a situation in the Uttaradesa (Northern Sri Lanka) which was to prove of some importance in the future for the gradual Tamilisation of the region.” He mentions the instances when Sirinaga, Manavamma and Pandyan king Sri Mara Sri Vallabha attacked and took control of the north before proceeding to Anuradhapura. The events of the ninth and the tenth centuries led to the increase of Tamil settlements in Sri Lanka. The Culavamsa speaks of ‘the many Damilas who dwelt (scattered) here and there' in the middle of the ninth century. The movements of troops between Sri Lanka and South India led to an increase in the number of Tamils resident in Anuradhapura and its environs. In the reign of Sena II, a Demela adhikari named Mahasattana worked in Anuradhapura. Reference found in the 10th Century records about dues from Tamil allotees (Demela Kudi) may mean that by that time Tamil settlers had increased heavily that a levy of a separate impost had to be imposed on them. In the 10th Century, there are references to immunity grants to Tamil allotments (Demela kaballa), land enjoyed by the Tamils (demelat valademin) and village land belonging to Tamils (Demela gam bim). These make it clear that there were areas set aside for Tamils. Tamil loan words mainly relating to administrative ranks and military service which occur often in the texts of Sinhalese inscriptions, testify to a presence of a considerable number of Tamils living in Sri Lanka during that period. They were concentrated in important administrative centers, market towns, harbours and other strategic centers. Most of the Tamils in the Anuradhapura Kingdom were Hindus. Religious institutions of the Tamils were established and supported chiefly by the mercantile communities. Some Saivite ruins, termed the Tamil ruins, have been unearthed in a section of the northern quarter of Anuradhapura. These ruins consist of Saiva Temples and residences for priests. On the basis of these findings, Indrapala ( Indrapala, K.The Evaluation of an Ethnic Identity - The Tamils of Sri Lanka, MV Publications, Sydney 2005) observes that Tamil settlements were widespread in the western region and in the north-eastern coastal belt during the early period of the Christian era. They enjoyed political authority both in Anuradhapura kingdom and in other regions and played a significant role in the trade between Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. Prof. Sitrampalam and Senior Lecturer Kunarasa, both of Jaffna University, and others say that sections of those Tamils migrated to the north and east when the kings of the second Lambakanna dynasty curbed the influence Tamils enjoyed in the Anuradhapura kingdom. They were also attracted to the north and east as the Jaffna Kingdom, the chieftaincies of Vanni, Trincomalee and Batticaloa emerged powerful. Pandyan and Chola invasions helped this process. Tamil inscriptions, coins and other Hindu remains of the eleventh and twelfth centuries are numerous in the northern and eastern regions. The transformation of the present eastern Province into a Tamil area may well be said to have began in the eleventh century. Pandya and Chola invasions prompted a steady flow of immigrants into the north and the east. Magha’s reign, in Polonnaruwa and Jaffna, where he revived Saivaism and established an administrative structure brought additional settlers from all parts of Tamil Nadu. Special settlements seem to have been established during Chandrabhanu’s regime also. Place names like Chavakachcheri, Chavankoddai and Chavakakoddai denote the settlements created by him. The Pandyan invasions during Chandrabhanu’s and his son’s periods also would have brought in a fresh influx of immigrants. This flow into the Jaffna peninsula increased with the establishment of the Jaffna Kingdom. Kalinga Magha’s very first act after building the new city of Nallur was to write to other Tamil kings of Tamil Nadu calling for colonists. Yalpana Vaipava Malai states that a number of families came over with all their slaves and dependents. They were settled in Thirunelveli, Mailiddi, Tellipalai, Inuvil, Puloli, Pachchilaippalli, Tholpuram, Koyilakandi, Irupalai, Nedunthivu and Velinadu (now called Pallavarayankaddu). Migration into the Jaffna peninsula and Vanni increased following the conquest of the major portions of Tamil Nadu first by the Muslims and then by the Vijayanagar Kingdom. The administration of most parts of Tamil Nadu was done by Telugu-speaking officials during the Vijayabagar period. At that time Jaffna kingdom was the only state that existed for the Tamils. Expansion The strong institutions built by the first five kings were the base that helped the next six kings – Varothayan (1302-1325), Marthandar Perumal (1325-1348), Gunapushanan (1348-1371), Virothayan (1371-1380), Jeyaweeran (1380-1410) and Gunaviran (1410-1446) – to lead the Jaffna Kingdom to its height of power. In that period of 144 years Tamils of northern Sri Lanka became a force to reckon with and they extended their territory up to Gampola in the central highlands and to Puttalam in the western coast. K.M. de Silva observed in History of Sri Lanka, “By the middle of the Fourteenth Century, the Jaffna kingdom had effective control over the north-west coast up to Puttalam. After the invasion in 1353, part of the Four Korales came under Tamil rule and thereafter, over the next two decades, they probed into the Matale district and naval forces were dispatched to the west coast as far as Panadura. They were poised for the establishment of Tamil supremacy and were foiled in this by the defeat inflicted by the forces of the Gampola kings in 1380.” The fifth king Varothayan was the architect of the rise of the Jaffna Kingdom. He ruled under the throne name Segarajasekaran III. His first task was to settle the dispute between the Sinhala and Tamil residents of Jaffna. He brought that about by addressing the grievance of the Sinhala-Buddhists. He restored to them the privileges they had enjoyed earlier. Then he stabilized his regime in Vanni by defeating the chieftain who refused to acknowledge the suzerainty of the Jaffna Kingdom and replaced him with one loyal to him. He defeated an invasion by a prince from Tamil Nadu in the Battle at Kachchai in Vanni. The Jaffna University publication ‘Yalpana Irachiyam’, traces with the help of inscriptions and literary evidence available in the Sinhala literature the progress of the southward expansion of the Jaffna Kingdom. It finds the roots of the expansionist period in the steady and purposeful policy initiated by Varothayan. He made use of the weakening of the Pandyan Kingdom following the invasion by the Delhi Sultanate and the confusion that prevailed in southern Sri Lanka to assert his independence. He also gave financial assistance to the Pandyans to help their struggle against Malik Kafur’s army. Malik Kafur captured and looted Madurai in April 1311 and subsequently Muslim rulers raided that ancient city. In 1323 Madurai came under the Tughlaks. Varothayan who ruled the Jaffna Kingdom during that period helped the Pandyan king again by providing financial help. In the south, Parakramabahu IV who ascended the throne in 1302, the same year Varothayan became king, was ruling from Kurunegala. During the latter part of his regime there was confusion. The second part of Chulavamsa which ends with his reign does not give any details of the fate that befell him. Bhuvanekabahu IV (1341-1351) shifted the capital to Gampola and was its first king. K.M. de Silva says, “The reasons for the shift to Gampola are not really known, but there is some literary evidence to suggest that the king left Kurunegala because of internal strife in the kingdom. This was the period when the Ariyachakravarthi of the northern Tamil kingdom were attempting to expand their frontiers.” The sixth Ariyachakravarthi, Marthandar Perumal, succeeded his father Varodaya in 1325 and ruled for 23 years under the throne name Pararajasekeran III. He continued his father’s policy of expansion. He inherited a wealthy regime which his father has assiduously built. His father had accumulated wealth by raiding Anuradhapura, exacting tributary payment from many minor rulers in Vanni and north central and northwestern parts of Sri Lanka and from the pearl fishery, which he dominated and fostered. Iban Battuda, the Muslim traveller, who had been earlier in the Delhi Sultan’s court and had travelled through Madurai to Sri Lanka, has recorded with astonishment his immense wealth, the ‘hundreds of ships’ that crowded the harbour and the mighty navy he had at his command. Marthandar controlled the northern trade routes to India and China. Marthandar Perumal died in 1348 and his son Gunapushanan succeeded him and ruled the Jaffna Kingdom until 1371 under the name Segarajasekeran IV. Vikramabahu III (1357-1371) was in power in Gampola. Five years after he ascended the throne, in 1353, Gunapushanam, the seventh ruler of Jaffna, invaded Gampola and captured many Kandyan districts. The Kotagama and Lahugala inscriptions refer to an intrusion by an Ariyachakravarti into Gampola and the capture of the Four Korales and other northern portions of the Gampola Kingdom. The king fled but later agreed to be a tribute-paying subordinate. The Kotagama inscription which is in Tamil refers to the conquest of the Four Korales by one Aryan from Singhai Nagar. An inscription found in Madawala in Harispattuwa says the Ariyachakravarthi appointed Brahmin tax collectors. Vikramabahu III’s minister Alakesvara led the resistance to the Tamil army. Alakesvara was a descendent of Nissanka Alagakkonara who came to Sri Lanka from Kanchipuram. His was one of the families that moved to Sri Lanka following the Muslim invasion of Tamil Nadu in the 14th Century. They embraced Buddhism and served in the courts of the Sinhalese kings. Though abandoned by the king Alakesvara stayed back and took over the resistance to the Tamil army. He raised an army, built forts including the one at Sri Jayavardhanapura, Kotte. It took him about two decades to make all these preparations. The Tamils meanwhile stationed their army at selected points and collected taxes. Alakesvara launched his attack in 1371 when the rising Hindu power, the Vijayanagar Empire, snatched Madurai from the Delhi Sultan and annexed it to its vast kingdom that embraced the whole of present Karnataka, the southern part of Andhra and Tamil Nadu. Gunapushanan died during this critical period and the eighth king Virotayar (1371-1380) who assumed the throne name Pararajasekeran IV succeeded him. He had to face the threats from the Vijayanagar Empire and from the Sinhala south. The Vijayanagar Empire started in Kannada-speaking Mysore (now Karnataka) was the Hindu reaction to the Muslim rule in Deccan in early 14th Century. It grew into a powerful empire within five decades and its rulers captured Madurai from the Tughlaks in 1371. Alakesvara provoked the Jaffna king by arresting and killing his tax collectors and by attacking the Tamil military posts in Gampola and Sri Jayewardenepura. Enraged, Varothayar sent the army overland to Matale and the navy to Panadura. The army was defeated and the naval ships that reached Panadura were burnt.

Virotayar was, at that time, embroiled with the Nayakas, the Vijayanagar governor who replaced the Tughlaks, in a grim struggle for survival. The Nayakas demanded tribute from the Jaffna Kingdom to which Virotayar agreed. While the Jaffna Kingdom was suffering the effects of the defeat Alakesvara inflicted on it, the foundation for the Kotte Kingdom was laid. Bhuvanekabahu V (1371- 1408) was the king at Gampola though Alakesvara wielded actual power. Though the Tamils had been expelled from Gampola the king felt that the Tamil pressure had not been finally eliminated. He moved to the fort at Sri Jayavardhanapura, Kotte, thinking it was safe. Jayaviran (1380-1410) ascended the throne on the death of his father in 1380 as the ninth King of Jaffna and assumed the throne name Segarajasekeran V. Bhuvanekabahu V attempted to take control of the pearl fishery and Jayaviran sent a large army to Gampola and the navy to Kotte. The army marched to Gampola and camped there. The navy landed troops at Panadura and the soldiers proceeded to Sri Jayavardhanapura and set up guard points around it. The king, Bhuvanekabahu V, who succeeded Vikramabahu III in 1371, fled and it was left to Viravahu, son-in-law of Alakesvara to defeat the Tamil army. Viravahu captured the crown and proclaimed himself the ruler. Thereafter there was confusion at Gampola and Kotte became preeminent. The defeat also weakened the Jaffna Kingdom. The 17 year rule Literary evidence shows that Jayaviran sent another expedition in 1408 to Kotte when the king refused to pay tribute. Gunaviran (1410- 1446), the tenth king, ascended the throne in 1410 as Pararajasekeran V when the Kotte kingdom was in disarray. Then in the next year, Parakramabahu VI (1411-1466) was crowned the King of Kotte. He started strengthening the kingdom. He emerged as the great Sinhala ruler. His greatest achievement was the conquest of the Jaffna Kingdom. Parakramabahu sent his adopted son Sapumal Kumaraya (birth name Senpaga Perumal) to capture the Jaffna Kingdom. Sapumal Kumaraya accomplished his task in many stages. Firstly, he conquered the Vanni chieftains, the tributaries to the Jaffna Kingdom. Then he tried to march to Jaffna but Kanagasuriyar Ariyachakravarthi who succeeded Gunaviran in 1446 and ruled under the name Segarajasekeran VI repelled the invader. Sapumal Kumaraya mounted a second invasion in 1450 which succeeded. Kanagasuriyar fled to South India with his family. Sapumal Kumaraya entered Nallur, killed all those who resisted him, and destroyed all the buildings including Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil, which was then at Kurukkal Valavu, He ascended the throne in the name Sri Sanghabodhi Bhuvanekabahu. Prof. S. Pathmanathan, in his book Yalpana Irachiyam – Ariya Chakravartigal, says that Sapumal Kumaraya, realizing his folly and to win the confidence of the people rebuilt the Nallur temple, and built palaces and houses in Panadra Vallavu and Sankili Thoppu area and promoted Hindu worship and favoured the Tamil subjects. The news of Sapumal Kumaraya’s victory was celebrated by the Sinhalese and Sapumal Kumaraya’s glory was sung in the Kokila Sandesaya (Message carried by Kokila bird) written in the 15th Century by the Principal Thera of the Irugalkula Tilaka Pirivena in Mulgirigala. The book contains a contemporary description of the country traversed on the road by the cuckoo bird from Devi Nuwara (City of Gods) in the South to Nallur (Beautiful City) in the North. The relevant portion reads, “A valiant prince, the guardian of realm The capture of Jaffna is one of the major events that promoted Sinhala pride and nationalism. It is still seen as victory the Sinhalese won over the Tamils. The conquest of Jaffna lasted only 17 years (1450-1467). It ended when Sapumal Kumaraya hurriedly returned to Kotte in 1467 when he heard about Parakramabahu VI’s death and about the coronation of Jeyaweera (1466-1469), Parakramabahu VI’s grandson. Sapumal Kumaraya appointed Vijayavahu as the king of the Jaffna Kingdom before he returned to Kotte. Parakramabahu VI’s death created confusion in Kotte and that facilitated Kanagasuriyar’s return to his kingdom. In Kotte Sapumal Kumaraya defeated Jeyaweera in 1469 and ascended the throne under the name Bhuvanekabahu VI (1469-1477). His son Panditha Parakramabahu VII succeeded him but was killed by his uncle Ambulugala Raja who adopted the name Vira Parakramabahu VIII (1477-1489). He was succeeded by his son Dharma Parakramabahu IX (1489-1513). His brother Vijayabahu VI ruled a portion of the kingdom as his co-ruler. They were in power when the Portuguese arrived in 1505. In Jaffna, Kanagasuriyar and his two sons, Pararajasekeran and Segarajasekeran, returned with their army, killed Vijayavahu and regained their lost kingdom. Pararajasekeran played a vital role in winning the battle. Kanagasuriyar ruled from 1467 till his death the next year. His elder son Pararajasekeran (1478-1519) succeeded him.

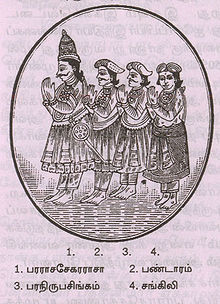

Pararajasekeran did not adopt the title Singhai Ariyachakravarthi. Kunarasa in his book Jaffna Dynasty gives the reason. The first eleven kings of the Jaffna Kingdom had used the title Singhai Ariyachakravarthi and they adopted the royal names of Segarajasekeran and Pararajasekeran alternatively. Since Kanagasuriyar had named his two sons Pararajasekeran and Segarajasekeran they decided to abbreviate the traditional royal title to Singhai. Singhai Pararajasekaran’s 41-year rule was the Golden Era of the Jaffna kingdom. He was content with control over the Jaffna peninsula and the neighbouring coastlands. He was not inclined to challenge the authority of Kotte south of Mantai. The Kotte kings who were preoccupied with their own problems, made no attempt to regain the north, although they continued to assert claims to overlordship over Jaffna. Though the successors of Parakramabahu VI continued to regard themselves as chakravarthis of the entire Sri Lanka, in practice their effective power was limited to Kotte. Several chieftains, big and small, ruled the territory between the Kotte and Jaffna Kingdoms and the eastern portion of the country. Some of them were tributaries of the Jaffna Kingdom and some others were subservient to Kotte. The bigger principalities were autonomous. The Jaffna and Kotte kingdoms were militarily weak and they left them alone. The two brothers who worked together made their period a golden era. Pararajasekeran emerged a great builder, administrator, a Tamil scholar, educationist and astrologer. He beautified the Nallur town, renovated Sattanathar Temple, Veyilukantha Pillair Temple, Kailatanathar Temple, and Veeramakali Amman Temple. He built a park and a tank. His younger brother Segarajasekeran organized a Tamil Sangam on the lines of the Madurai Tamil Sangam of yore. He established schools and villages and wrote a book on astrology known as Segarajasekaram and a book on medicine under the title Pararajasekaram. The celebrated Sanskrit work Megathoothu written by Kalidasa was translated into Tamil during this time by their brother-in-law Arasakesari. Pararajasekeran had four sons: Sinhavahu, Pandaram. Paranirupasingham and Sankili. Following tradition Pararajasekeran named the eldest son Sinhavahu as his successor but he died of poisoning. Pararajasekeran then appointed his second son Pandaram as the crown prince. Paranirupasingham, like his uncle Segarajasekeran, was a skilled physician. His father Pararajasekeran sent him to treat the Queen of Kandy who suffered an excruciating stomach pain. That was done in response to a request from the Kandy king. Paranirupasingham cured her and the Kandyan King rewarded him with costly presents. Before he could return crown Prince Pandaram was stabbed and killed while he was walking in the garden by an unknown person. Sankili took over the kingdom and ascended the throne in 1519 under the royal name Sankili Segarajasekeran. (Next Friday: Tamils Lose Sovereignty) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Index |

|||||||||

|

||||||||||