Rev. William Carey

Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by T. Sabaratnam, September 16, 2010

A journalist who reported the Sri Lankan ethnic crisis for over 50 years

|

Hindu revival preceded Buddhist revival by almost two decades. Two factors helped the Hindus to react to the Christian missionary activities earlier than the Buddhists. Firstly, they were influenced by the Hindu revival movements in India, particularly by the movements in Bengal. Secondly, Hindus of Jaffna faced the onslaught of the vigorous activities of the American Ceylon Mission which was barred by the British from working outside the peninsula.... [Navalar's] determined defence of Saiva doctrine and practices created a solid resilient foundation of self-consciousness among the Tamils of Sri Lanka. This revitalized sense of purpose and identity became the turning point in the history of the Tamils of Sri Lanka. |

Hindu Revival

In the early decades of the 19th Century large numbers of Christian schools were opened in Sinhala and Tamil regions of Sri Lanka. Buddhist and Hindu children who attend those schools were compelled to follow classes in Christianity. The Christian education was modeled to instill into the students Christian values.

Buddhists and the Hindus realized soon that the proselytizing efforts and the spread of western values were threatening their faiths and traditional cultural values. They reacted by reforming their religions and refreshing their cultural practices.

|

Rev. William Carey |

Hindu revival preceded Buddhist revival by almost two decades. Two factors helped the Hindus to react to the Christian missionary activities earlier than the Buddhists. Firstly, they were influenced by the Hindu revival movements in India, particularly by the movements in Bengal. Secondly, Hindus of Jaffna faced the onslaught of the vigorous activities of the American Ceylon Mission which was barred by the British from working outside the peninsula.

Protestant Christianity was introduced in Bengal before it was brought to Sri Lanka. Christian missions started theiractivities in Bengal in the 1790s. The Baptist Missionary Society (BMS), the London Missionary Society (LMS) and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) were the first missions that served in Bengal. The Scottish Missionaries and the Irish Presbyterians also went there.

The first organised missionary work in Bengal started under William Carey, a Baptist, who reached Bengal in 1800. Carey started the first Baptist Mission in that year at Serampore in Culcutta. The LMS too started its mission work under Nathaniel Forsyth in 1798. The CMS entered in 1813.

The Baptist Mission ran into conflict with the Muslims in 1809 when it made some adverse comments about Prophet Muhammad in a pamphlet it published. Muslims rioted against it. Thereafter the Christian missionaries concentrated their activities among the Hindus.

They adopted two strategies: infusing Christian ideas through propaganda and education and attacking the doctrine and practices of Hinduism. They introduced the teaching of science and environmental studies to foster rational thinking. They translated the Bible and distributed it among the people. They also promoted the study of oriental classics. They published parts of Ramayana and made use of it to prove that Hinduism was “a bundle of myths”.

The missionary attack on the doctrine of Hinduism was concentrated on the question of worship of several idols and their attack on Hindu practices was focused on the caste system, sati (burning of the wife in the funeral pyre of her husband), child marriage, the dowry system and the lack of orderliness in temples. They voiced their criticism during their preaching and through pamphlets. They also ridiculed the puranic stories.

Hindus reacted in two different ways. The Hindu orthodoxy launched an anti-Christian crusade. The Arya Samaj founded by Dayananda Saraswati (1824-1883) was the outcome of that anti- Christian stand. His movement propagated the Aryan religion and advocated the reconversion of converts to Islam and Christianity back to the Vedic faith. The stance of the Arya Samaj was that all non-Vedic religions were false. The Vedas alone are God inspired and the Vedic religion alone was true, its adherents insisted.

The Hindus who were educated in the missionary schools reacted in a different way. They accepted that Hinduism had gathered a lot of superstition and unwanted practices and it should be reformed and purified.

Brahmo Samaj, founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772- 1833) on August 20, 1828 at Calcutta (now Kolcatta), adopted the reformist approach to meet the Christian missionary challenge. Basing its thinking on Upanishad, ancient Sanskrit Hindu texts, the new organization preached that Hinduism held that God is one. He is Almighty. He is omnipresent and everlasting. Without His grace nothing will move. Brahmo Samaj held that there is no conflict between Hinduism and Christianity. It said that all religions in fact preached the existence of One Almighty God.

Roy accepted some of the Christian criticisms of Hindu practices and traditions and launched a vigorous campaign to change them. Chief among them were sati, child marriages and the caste system. He convinced the British rulers in 1829 to outlaw sati. He founded a newspaper and launched a campaign against child marriages, animal sacrifice and the caste system.

Roy’s reform movement brought about a change in the thinking and attitude of the Hindus and blunted the criticisms of the Christian missionaries. Roy’s propaganda brought new confidence among the Hindus.

Ram Mohan Roy’s reform movement also countered the Christian missionaries by starting Hindu schools and colleges. The Hindu College in Bengal was opened in 1817 the year in which the Christians opened the Serampore College.

Historians estimate Roy and his Brahmo Samaj movement as the prime factor that acted as a break on the spread of Christianity in India. And his movement had its impact on Tamil Nadu and Jaffna. Though the situation in Jaffna was different the Hindus there adopted Brahma Samaj as their model.

Jaffna’s reaction

In Jaffna, Protestant missionaries faced stiffer opposition to their conversion efforts. Unlike in Bengal, the environment in the Jaffna peninsula was hostile to conversion. The people of the Jaffna peninsula had faced mass conversions twice in the past 200 years. They were first converted to Roman Catholicism by the Portuguese and then to the Protestant Christianity of the Reformed Roman Dutch Church. They were in the process of returning to their traditional religion, Saivaism, fostered during the 400 years Jaffna Kingdom ruled them.

Hinduism was the religion Tamils who settled in Sri Lanka practiced from pre-historic times. The Ramayana provides evidence for that. Ravana was a great Hindu king. Four Hindu temples dotted the four corners of the island. Archaeological, epigraphic and numismatic evidence confirm the prevalence of Hinduism throughout Sri Lanka long before Buddhism was introduced. Hinduism was in the veins of the Tamil people.

The Christian missionaries from Britain and America were thus looked with suspicion dashing the hope of the missionaries that thousands of ‘pagans’ would embrace their religion. Rupert E. Davies in his book Methodism gives the reason for their failure to attract converts thus,

In Asia the progress was necessarily much slower. For the religions which there confronted the Christian missionary were as developed in their ideas as the one that was being imported, and had the additional advantage of symbolising the proud nationalism of the ancient peoples of the East ... The early attempts to reach the high-caste people had failed utterly, and it became a matter of policy to pursue evangelism by the indirect path of schools, colleges, and hospitals.

The missionaries who investigated the causes for the failure of the conversion effort identified rigid caste and dowry systems that dominated the Jaffna people as their main impediments. Thus their first attack was on the social organization and practices of the Jaffna Tamils. They called caste and dowry systems “social evils” that should be eradicated from among the Tamils.

The missionaries found that even those converts who studied in their schools returned to Hinduism after marriage. The frustration caused by such behavior of the Tamils is reflected in the following extract which deals with caste. The extract taken from a correspondence between two missionaries was quoted by Murugar Gunasingam in his book, Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: A Study of its Origins.

It (caste) is an evil… that requires a perpetual watch, a perpetual effort and thus it will take a lot of time to obliterate it.

On the evil of the dowry system Wesleyan missionary John Rhodes wrote,

Here is one of the common cases which cause so much misery. An educated man finds himself united to a wife who cannot at all sympathize with him but also finds the dowry a mirage which he never gets. If God would blast this accursed marriage system, one of the greatest barriers to the spread of Christianity, if not the greatest, should be removed and certainly a principal source of anxiety with our elder boys would disappear.

|

Siva, Parvathy, Ganesh and Murugan |

Frustrated that their efforts to convert the Hindus of Jaffna Christian missionaries went into the offensive. They denounced the Hindu doctrine and practices in the street-corner meetings they held near the popular temples.

As in Bengal their first attack was on the worship of several gods.

They asked the Hindus, “If you worship so many Gods can you attain salvation?” Hindus initially answered saying that the Christian missionaries were asking that question because they failed to understand the basic philosophy of Hinduism. Some Hindu scholars gave the reply that Brahma Samaja adherents gave in Bengal: In Hinduism God is one, varies deities manifest the different attributes of God. The firm formulation of the answer of the Hindus had to wait till Arumuga Navalar published the simplified textbook on Hinduism in the form of question and answers, the Saiva Vinavidai.

Navalar's answer put to rest the Christian criticism of the worship of several gods. The following is the translation of Navalar’s formulation:

Who created the universe?

Siva.

What are Siva’s attributes?

He is eternal, omnipresent, omnipotent and all-knowing.

What are his activities?

Creation, protection and destruction.

Christians also ridiculed Hindu practices. They called the wearing of vipoothi, santhanam and kunkuman on the foreheads tribalism. They called the drinking of theertham and eating of panchamirtham unhygienic. They called the observance of fasts and eating vegetarian food on Fridays foolish.

Christian missionaries specially targeted the worship of Murugan for criticism and ridicule. They did it because Murugan worship was popular among the Tamils of Sri Lanka, particularly among the people of the Jaffna peninsula.

According to Hindu theology Murugan was the second son of Siva. He was next to Ganesha who is portrayed as the God of Success. Murugan was the Destroyer of Evil. Murugan is also known by the name Skanda (Kanthan in Tamil).

Ancient Tamil literature eulogizes Skanda. The Tamil work Tirumurugatruppadai by Nakkeerar of the Sangam period reveres the Aru Padai Veedu ( Six Abodes) of Skanda. The abode associated with his birth is at Tirupparankunram near Madurai and it is over 2000 years old. The Tamil works Akanaanooru and Puranaanooru of the Sangam period also refer to the abode Tiruchendur. Silappadikaaram refers to Tiruchendur and Tiruchengode as abodes of Murugan.

Christians also chose Murugan worship because the three foremost Murugan temples - Nallur Kanthaswamy temple, Maviddapuram Kanthaswamy temple and Sella Sannithy temple - attracted thousands of devotees. Devotees take kavadi and perform pirathaddai (rolling round the temple premises) and other penance in those temples. Shrines of Murugan are also part of all Sivan and Ganesha temples in the Jaffna peninsula.

Christian preachers stood outside those temples and delivered sermons and distributed leaflets ridiculing Murugan worship and the practices associated with it. Such actions irritated the Hindus and drove them away from the Christian preachers. A few instances where they ridiculed the preachers were also reported.

Opposition Emerges

The first instance of open opposition to Christian criticism and ridicule emerged in 1828 when the Batticota Seminary decided to teach Kantha Puranam (The Story of Lord Murugan) to its students. The teachers of the seminary decided to teach Kantha Puranam to prove that the story of Murugan was pure fiction. Kantha Puranam was first composed in Sanskrit under the title Skanda Puranam by Adi Sankara in the first century AD. It narrates the legends related to Skanda. Its Tamil version Kantha Puranam was created by Kachiappa Sivacharyar of Kanchipuran in the 14th Century. Kantha Puranam is highly valued for its spiritual and literary qualities.

The teachers got selected portions of the book which is poetic form written into prose and started teaching it. Hindus created a stir and exerted social pressure on the students compelling them to boycott the classes. The students kept away from that class and that forced the seminary to abandon its project. But the seminary claimed in its annual report that what they had taught had made the students realize that the book was filled with the most incredible fictions many of which were of immoral tendency. The teachers told the students that the marriage of Murugan to Valli and Theivanai was bigamy, an immoral act.

Though the preachers at the Batticota Seminary claimed that they had proved their point by teaching Kanda Puranam it instilled in the Hindus an anti-Christian revulsion. That aversion was exacerbated by two more actions of the teachers at the mission.

Rev. Daniel Poor, the principal wrote five tracts asking the Brahmins to consider the teachings of Christianity. He got them delivered to the Brahmins through his students. He tried to show through those tracts that the tenets of Hinduism had no validity. This was interpreted by the Hindus as a direct challenge to their religion.

Rev. Henry Richard Hoisington who taught astronomy (he became the second principal of Batticota Seminary) ridiculed astrology. He was also behind the publication of the annual almanac Thiriyangam; which challenged the Panchangam in which the people had faith. Although it was published in the name of Vannarponnai Vellalan Mylvaganar Somasekarampillai people knew that Hoisington was behind it.

The Batticota Seminary which established a printing press in 1820 published anti- Hindu pamphlets in Tamil on a regular basis. Some of them were: Kiristuvin Inpattuvam (Happiness of Jesus), Oyvu Nal (A Day of Rest), Cittanta Kalakku (Confusion of Sittantha), Pauranika Matam (Religion of Puranas), CanmarkkamYaritattil (Who Possess Good Morals), Putiya Erpatu (New Testament) and Cristuvin Makimai (Greatness of Jeseus). They also published the pamphlets Blind Way ana The Hindu Triad which questioned the validity of Hindu beliefs and reliability of the Hindu puranas.

Hindus did not have a press of their own to reply. So popular Saiva poet Muttukumara Kavirayar (1780- 1851) wrote two long poems, Jnanakkummi (Kummi Song on Wisdom) and Jesumataparikaranam (Abolition of the Jesus Doctrine). In them he criticized the Bible and the Christian doctrine and practices just as the American missionaries ridiculed the Kantha Puranam and Hindu doctrine and practices. The poems were published in Madras in 1827 and widely distributed in Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. Those poems served as the starting point of the confrontation between the Christians and the Hindus in Jaffna and Tamil Nadu.

Vedanayaka Shastriar, a Protestant poet in Madras answered Muttukumara Kavirayar with the poem Shãstirakkummi (A Satirical Poem on the Superstitions of the Hindus) which ridiculed the beliefs of the Hindus. The conflict continued in Madras with a Hindu poet publishing Vetavikarpa (The Misunderstanding of Veda), a condemnation of the Bible, and a Catholic responding with Vetavikarpa tikkaram (Contempt for ‘The Misunderstanding of Veda).

The conflict intensified in July 1841 when the Batticota Seminary launched a bilingual bi-monthly newspaper Morning Star and Uthaya Tharakai which launched an attack on the Hindus. The attackers concentrated on ridiculing idol worship, temple rituals and called Saivaism a cult of devil worship. In its second issue its editor Henry Martyn wrote a scathing editorial in which he said,

There is nothing in the peculiar doctrines and the percepts of the Saiva religion that is adopted to improve a man’s moral character or fit him to be useful to his fellow men…if the world were to be converted to the Saiva faith, no one would expect any improvement in the moral and happiness of men. Everyone might be as a great liar and cheat, as great an adulterer, as oppressive as the poor, as covetous, as proud, as he was before without the purity of his faith.

Henry Martyn studied at the Batticota Seminary and taught mathematics and physics there. He was a prolific writer and wrote a poetical drama in Tamil, Esther Vilasam, a drama based on the Book of Esther in the Bible. The play was not printed. When he was appointed as the Editor of Morning Star he became the first Sri Lankan editor of an English newspaper in Sri Lanka.

After the death of his first wife in 1842 he married a Catholic lady, left the seminary and gradually shifted to Roman Catholicism. He became an anti- Protestant and wrote the Lamentations of Mary under the Cross, in Tamil which depicted the lamentations of Mary at the crucifixions.

Martyn in his editorial in the mid-August issue called Saivites devil worshipers. The relevant portion said,

Oh! What a madness of this people who live in darkness and foolishly practice their ritual ceremonies to the devil (Saiva deities) at the same time indulging in all sorts of sin in the temple. Please leave all these madness and darkness and visit the real God of Jesus and pray for your salvation.

That editorial provoked the Saivites. One of them was Arumugam Pillai, a Saivite who was teaching at the Wesleyan Mission School. He taught English Language for the lower classes and Tamil for the upper classes. He was also assisting the school principal Rev. Peter Percival to translate the Bible into Tamil. He sent an article titled “The Saiva Point of View” to Martyn. He signed the article as “Son of Siva”.

The editor published it as he wanted to give the other point of view. In that article the writer maintained with evidence from the Bible that Christianity and Jesus himself were rooted in the temple and the temple rituals of the ancient Israelites. The article admonished the missionaries for misrepresenting their own religion and concluded that in effect there was no difference between Christianity and Saivaism as far as idol worship and temple rituals were concerned. He said,

The Israelites who were chosen by God as his own children believed that the Lord who dwelt in the ark made of wood, and who lived between the Cherubims had bestowed grace upon them. The Saivites believe that God dwells in the image. They [the Israelites] made a sanctuary for the worship of God. The Saivas build temples. The Israelites worship Cherubim and bronze serpents. The Saivas worship the images made of gold, and silver. The Israelites had shew bread and wine in their sanctuaries. The Saivas keep fruit as prasada. The Israelites had incense. The Saivas have it too. The Israelites burnt heifer and took its ashes for their use. The Saivas use ashes from the dung of a heifer.

The editor knew that he had a difficult task in responding to this long and carefully wrought document. It took him three issues to do so. He understood this calculated challenge, for he referred to its contents as “the pretended Resemblance between the rites and ceremonies of the Mosaic dispensation and those of the Sivas.”

Emergence of Hindu Consciousness

As Murugar Gunasingam remarks (Sri Lanka Tamil Nationalism, page 122) Hindus realized that the Christians were attacking not only their religion but also their religious-based cultural life. That realization stimulated their desire to resist the anti-Saivite attacks by the Christians and a desire to revive and reform their religion.

According to a report published in the Morning Star of October 20, 1842 over 200 prominent Hindus met in the mandapam (prayer hall) of the Jaffna Vannarponnai Sivan Kovil on September 30, 1842 to work out a plan to counter that attack. The meeting was convened by five wealthy Hindus but Arumugam Pillai who was present at the meeting was the livewire behind them.

Among the others were: Sathasiva Pillai,Swaminatha Iyer, Natarajah, Viswanatha Iyer, Kanthaswami Pillai and Arumuga Chettiyar.

Most of the speakers gave vent to their anger. They said that they should react fast and decided to open a school to teach Vedas and Agamas to their children as a means to prevent conversion. They decided to collect money from sympathizers to fund the school. They also decided to buy a printing press.

The school, Saivaprakasa Vidyasalai was opened on Saturday, October 22, 1942. It adopted the curriculum and teaching methods practiced in Christian schools. That project was abandoned because the government refused to register the school. Their decision to establish a printing press too did not materialize.

|

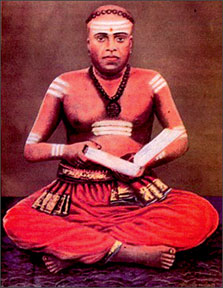

Arumuga Navalar |

Arumugam Pillai, the man behind this move, was born on December 18, 1822 in Nallur and grew in a highly Saivite environment. He completed his Tamil education at the age of twelve under the guidance of his father, Kanthar, a Tamil poet and playwright. Thus he had a sound foundation in Tamil literature. His mother Sivakami was a devotee of Siva. That gave him a firm devotion to Saivaism.

Arumugam Pillai later joined Wesleyan Mission English School, currently Jaffna Central College, for his English education when Rev. Peter Percival was its Principal. He was identified as a bright student and was appointed a teacher after he completed his education. He taught Tamil and English and helped Percival to translate the Bible into Tamil. He worked with Percival from 1841-1848.

While working with Percival he saw first hand the constant attacks on Saivaism and the tireless efforts made by the Christian missionaries to convert the people. They claimed that Christianity had begun to take root in the Jaffna soil and before long it would be a Christian country.

Arumugam Pillai was touched by the Hindu religious awakening that was taking place among the people and also the sense of helplessness that prevailed among them. He later admitted that he spent sleepless nights pondering how he could play a positive role to stem the tide of conversions.

Arumugam Pillai later wrote about the torments he underwent thus:

I have not made the efforts needed to promote the Saiva religion. What can be done in this matter? The Lord Siva gave me the great desire to promote the Saiva religion but I do not have the ability to achieve this. Why did He give me this desire and not to those who have the ability? Day and night this was my worry. My time is spent in heaving sighs and raving deliriously to others about this.

From the date of the Sivan Kovil meeting he worked out a plan to meet the Christian challenge. He selected as his model Bengal’s Brahmo Samaj which advocated reforms to Hinduism to ward off the criticisms of the Christians before meeting their challenge. He decided to copy the sermons delivered by the Methodist priests as the prime mode of preparing the Hindus to withstand the Christian attack. He named his ‘sermons’ pirasangam.

Arumugam Pillai prepared himself for the task he had selected for himself. He studied Sanskrit. He studied the Hindu scriptures: Vedas, Agamas and Upanishads. He also prepared the plans to reform Hinduism and the educational methodology.

Arumugam Pillai delivered his first pirasangam on December 31, 1847 at Vannarpanni Sivan Kovil after the evening pooja. The chief priest of the temple broke a coconut before the commencement of the pirasangam. The priest blessed Arumugam Pillai and announced that the coconut had broken evenly and that was a good omen. The priest also announced that he heard bells ringing inside the temple which was also a good sign. Arumugam Pillai’s pirasangam was followed by a discourse by Kartigesu Ayer who was helping him to reestablish the school. The historic event was held in a spacious shed put up outside the front wall of the temple.

The pirasangams were held every Fridays after the evening pooja. Arumugam Pillai spoke on different topics every week. The topics he dealt were mostly ethical, liturgical, and theological and included the evils of adultery, drunkenness, the value of non-killing, the conduct of women, the worship of the linga, the four initiations, the importance of giving alms, of protecting cows, and the unity of God. He attacked Christians and Hindus alike. He attacked the trustees and priests of Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil because they had built the temple not according to the Agamas and the Brahmin priests who served there were not initiated in the Agamas. He also opposed their worship of Vel as it did not have Agamic sanction.

Arumugam Pillai’s pirasangams were something new to the Hindu public. They differed from the tradition of reading of Puranas where one person read the poetic text and another gave the meaning and explanation. Such readings would stick strictly to the text. Arumugam Pillai, on the other hand, spoke on topical subjects including political developments. These pirasangams invigorated the Hindus. Hindu revival that was till that time confined to the educated section of the people spreads to the general public.

Arumugam Pillai left his job at Wesleyan Mission School in September 1848 and devoted his entire time to work for the revival of Saivaism. This irritated and angered the Christians. Christian missionaries and the Morning Star accused and attacked Arumugam Pillai and his anti-Christian campaign. That did not deter Arumugam Pillai. His determined defence of Saiva doctrine and practices created a solid resilient foundation of self-consciousness among the Tamils of Sri Lanka. This revitalized sense of purpose and identity became the turning point in the history of the Tamils of Sri Lanka.

Having laid the foundation Arumugam Pillai and the group of prominent Tamils proceeded to take the necessary steps to consolidate the Hindu revival. They were instrumental in restarting the Saivapiragasa Vidyasalai in Vannarponnai in 1848. Arumugam Pillai opened a similar school at Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu in 1854. In these schools he introduced the education system followed in the Missionary schools. He admitted around 20 students in each class and developed the curriculum which included subjects such as arithmetic, geography, history, English language and Tamil grammar besides Saivaism. Most of the teachers were his friends and acquaintances who were volunteers.

Arumugam Pillai also wrote the basic instruction materials for different grades on Tamil language – the Pala Padam series – and Saivaism – the Saiva Vina Vidai series.

Through the Saiva Vina Vidai Arumugam Pillai tried to imprint in the minds of Saiva children the basic concepts of that religion. Through that method he prepared the Saivites to answer the criticisms of the Christians. The very first concept he imprinted was that of One God.

The need to publish these school textbooks compelled Arumugal Pillai to buy a printing press. He went to Madras in 1849 with his colleague Sadasiva Pillai to buy one. On the way back they stopped at Thiruvavaduturai Aththeenam in Thanjavur, an important Saiva monastery. The head of the monastery asked Arumugam Pillai to preach. Impressed by his unusual mastery of the knowledge of Agamas, the head of the monastery conferred on him the title Navalar (learned). He has been known as the Navalar since then.

Navalar published two teacher’s guides, Cüdãmani Nikantu, a 16th Century lexicon of simple verses and Saundarya Lahani, a poem in praise of the goddess of devotion. They were his first effort at editing and printing Tamil works.

Navalar named his press established in 1849, Vidyaanubalana yantra sala and published the Bala Padam series. They were Navalar’s reply to the Bala Potham series published by the American Ceylon Mission. The third volume of that series contained 31 essays in clear prose, discussing subjects such as God, Soul, The Worship of God, Crimes against the Lord, Grace, Killing, Eating meat, Drinking liquor, Stealing, Adultery, Lying, Envy, Anger, Animal Sacrifice and Gambling.

Navalar's first major literary publication appeared in 1851, the 272-page prose version of Sekkilar’s Periya Puranam, a retelling of the 12th Century biography of the Nayanmars, the Saivite saints. In 1853 he published Nakkirar’s Thirumurukattuppadai, a devotional song on Murugan, with his commentary. This publication reinforced Murugan worship among the Saivites.

The missionaries launched an attack on Murugan worship pointing out that having two wives was immoral. Navalar replied the missionaries in his English language publication Radiant Wisdom explaining the wisdom behind the Murugan story. He showed the different levels of meaning of the story and charged the missionaries with the incapacity to understand the real meaning.

The Hindu-Christian confrontation intensified further in 1852 with the publication Bibiliya Kutsita (Disgusting things in the Bible) which he co-authored with Senthilnatha Ayer. Navalar followed that with another publication, a kummi song on the Wisdom of Muttukumara Kavirayar, a work he co-authored with S. Vinayakamurtti Cettiyar of Nallur which commented further on Muttukumara Kavirayar’s Jnanakkummi, the first Hindu response to the Christian criticisms of 1920s.

Then Navalar published his seminal work Saiva dusana parihara (The Abolition of the Abuse of Saivaism) in 1854, in which he said all the ridiculous things and superstitions mentioned in the pamphlets published by the Christians as found in Saivaism were also found in the Bible. He quoted what was said in the pamphlets and showed that a similar saying was found in the Bible. It became a training manual for the use of Saivites to answer the missionaries.

Carol Visvanathapillai replied with the pamphlet Supratheepam. It contradicted Navalar’s arguments and explained the Christian doctrine lucidly. In it he praised the missionary education and tormented Navalar.

Arumuga Navalar’s campaign instilled a new sensitivity and confidence among the Saivites. They developed the feeling that their religion was not as bad as the missionaries painted it. He created among the Hindus the sense that they need not change their religion because they were not under the shadow of death as the missionaries told them. Even those who had earlier embraced Christianity started returning to Hinduism. This resulted in the establishment of many Hindu schools and the growth of more political awareness among the Tamils.

Navalar had carefully whipped up the spirit of Hindu nationalism among the Jaffna Tamils and Bishop Sabapathy Kulendran acknowledged that with the comment,

"When comparing the promise Christian conversions showed in Jaffna at the beginning of the century to their disappointing results, this low rate of conversion was largely due to Navalar".

Navalar should also be credited with laying the foundation for the Christian community of Jaffna to move into the mainstream of Tamil nationalism with his contribution to the rediscovery of ancient Tamil literature and civilization, an opportunity the Christian community seized firmly. This helped to alter the incipient Hindu religious nationalism which emerged as an anti-Christian movement into Tamil nationalism with a linguistic base.

(Next week- Parallel Growth of Nationalisms)

--------------------------------------------------------------

Index

Emergence of Racial Consciousness

Religious Revival

Parallel Growth of Nationalisms

© 1996-2025 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.