Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 6: Birth of a unitary state by T. Sabaratnam, September 3, 2010

Cleghorn Minute Last week I highlighted three conventions and three treaties which establish that the Portuguese administered the territory they captured by defeating the Jaffna kings in battle as a separate unit. They permitted the people, as they agreed at the Nallur Convention, to be governed by their ancient customs and practices. The Dutch and the British till 1833 continued that practice. They also administered the territory that was under the Jaffna Kingdom in Tamil. Thus the territory that was under the Jaffna Kingdom during 1215- 1619 continued to be administered as a separate unit from 1619- 1833. As pointed out in the last chapter the British East India Company captured the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka in 1796. The East India Company which had been ruling the Madras Presidency since 1750 was directed by the British government to take over the Dutch possessions in Ceylon because Britain feared that they would fall into the hands of the French. Britain, a monarchy, was opposed to the French Revolution (1792- 1801) which resulted in the arrest of King Louis XVI of France in 1792 and his execution in January 1793. Great Britain formed a coalition with other monarchies and tried to crush the French Revolution that had become popular in Europe. That attempt failed. Five years later, in 1798, Britain formed a second coalition and inflicted heavy losses on France. Napoleon Bonaparte who was in Egypt during that period, returned and seized control of the French government and launched a war against the neighbouring countries. He captured Holland and its king fled to Britain. Fearing that the French would take over the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka and then attack India the British directed the East India Company to capture the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka. The British East India Company annexed Kotte and Jaffna to the Madras Presidency and made use of the Tamil tax collectors under its control to collect taxes in both territories. The East India Company took control of the pearl fishery and imposed several taxes including a tax on coconut trees. People of Kotte revolted and Britain took over the administration of the territories under the East India Company. It sent in 1798 Fredrick North and nine civil servants to take charge of the administration. The senior among the civil servants was Sir Hugh Cleghorn, a Scotchman. He was appointed Principal Chief Secretary and Governor’s Chief Advisor. He travelled throughout the territory under British control and was in charge of auctioning the rights for the pearl fishery. In a letter he sent to the British Government in June 1799 detailing the situation in Sri Lanka he wrote:

He advocated the takeover of the Sri Lankan possessions of the East India Company by the British Crown and recommended the continuance of the Portuguese and Dutch policy of administering the two territories the two nations occupied as separate units. Britain accepted that recommendation. The British administered the two territories separately till 1833. Though they annexed Vanni to the Tamil territory, they administered the Kandyan territory separately, honouring the undertaking they gave to the Kandyan chiefs. Thus after the capture of the Kandyan Kingdom there were three autonomous territories in Sri Lanka: Kotte, Kandy and Jaffna. Pandara Vanniyan One of the first decisions North took after the assumption of the office of Governor was to bring the entire country under British rule. Vanni and the Kandyan Kingdom were the only areas that remained outside their reign. The Portuguese and the Dutch had failed to subjugate those areas. North wanted to earn fame by capturing them. He started with Vanni. The origin of the Vanni chieftaincy is not clearly established but researchers maintain that human settlements in Vanni commenced in the first century BC. The Konesar inscription and old folk songs say sixty vanniyars accompanied the royal bride who came from Madurai in the first century BC to marry a king of Anuradhapura. Vanniars would have been brought from North Arcot in Tamil Nadu. The Vanniyars were settled in Vanni. Vanni came into the historical limelight around the beginning of the tenth century when the Pandyans invaded Sri Lanka and brought the northern province under their influence and control. Vanni’s importance increased during the period of the Chola invasion and Kalinga Magha gave importance to Vanni by making it one of his administrative divisions. G.C. Mendis in his book Early History of Ceylon (page 70) says Vanniyars occupied the territory between the Kotte and Jaffna kingdoms and acknowledged the supremacy of one or the other and remained independent whenever possible. He adds that the Vanniyars tried to be independent after the Pandyan and Chola invasions. They were tributaries of the Jaffna kingdom after it became powerful. Historically, the Vanni encompassed Mannar, Vavuniya, Trincomalee, Polonnaruwa, Batticaloa, Ampara and Puttalam hinterlands. But the Vanniyars in the Vanni region were powerful during the Portuguese and Dutch periods. The Vanniyars belong to the warrior caste with heroic and marital skills. According to folklore, seven Vanni chieftains who fought unsuccessfully against the Dutch committed suicide to avoid capture. They are still revered at Natchimar temples in the Vanni and Jaffna. With the capture of the Jaffna kingdom by the Portuguese in 1621 Vanni was under their nominal control and `Parangichetticulam` of the Vanni may have been the fort of the Portuguese. The Portuguese and the Dutch found the Vanniyars a formidable foe. Lewi, a Dutch commander praised their fighting spirit and said he had never met such resistance anywhere else in the world. He specially praised the valour of Vannichi Kurivichhci Nachiyar, whom he said was taken prisoner and detained in Colombo fort. Pandara Vanniyan, the last king of Vanni, was the most formidable of Vanni chieftains. He fought against the Dutch and the British. He formed an alliance with the Kandy monarchs in his bid to drive the British away. In his battle with the Dutch and the British he adopted conventional and guerilla warfare. In a surprise attack on the British garrison in Mullaitivu in 1803 Pandara Vanniyan’s forces, consisting mainly of Tamils of Vanni, overran the garrison and captured their cannons. The British forces under the command of Lt. von Drieberg withdrew to Mannar. Pandara Vanniyan’s forces overran the whole of Vanni and advanced up to Elephant Pass.

Vanniyan's victory was short-lived. The British forces under the command of Drieberg attacked from three fronts- Jaffna, Mannar and Trincomalee- and defeated Pandara Vanniyan, captured and executed him on August 25, 1803. The British forces burnt all the houses which caused the people to seek refuge in the forest. Some of the people migrated to the Jaffna peninsula. The power of the Vanni Chiefs was thus finally and effectually extinguished. Pandara Vanniyan became a folk hero and Pandara Vanniyan Nattu Koothu is popular among the Sri Lankan Tamil people even today. A tombstone was erected at the spot where he was defeated. It was damaged during the recent war following the Ceasefire Agreement. Kandyan Wars While consolidating the British rule by annexing Vanni Governor North turned his attention to the Kandyan Kingdom. His first attempt was to make it a British Protectorate through negotiations. He sent an emissary to Kandy in the pretext of congratulating Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe who succeeded his uncle Sri Rajathi Rajasinghe who died on July 26, 1798. The mission failed because Vikrama Rajasinghe who had followed keenly the British intrigues and strategies that led to the conquest of South India was suspicious of North’s intentions. He reasoned that it would be wiser to deal with the smaller countries like Portugal and Holland than with the British who had vast resources and the dream to conquer the world. North who had, as indicated in the last chapter, held a secret meeting with Maha Adikaram Pilimatalawe in Sitawaka, sent two British detachments to capture the Kandyan kingdom. North took that decision on the strength that Pilimatalawe’s men would guide the British forces through the secret mountainous routes to Sengadagala where the king stayed. He also believed in the exaggerated stories Pilimatalawe told him about the king’s unpopularity. The detachment that went from Colombo was led by Major-General Hay Macdowell and the one that marched from Trincomalee was commanded by Colonel Barbut. The British forces entered Sengadagala in February 1803 after a fierce battle. They found the city deserted. The British forces established a garrison and crowned Muttusami, the brother-in-law of the former ruler Sri Rajathi Rajasinghe, who had claimed the throne, as the new king of Kandyan Kingdom. Then the forces moved to Kandy. The British forces then encountered a series of difficulties. The Kandyans resorted to guerrilla warfare and inflicted severe damage on the British army. Locally recruited soldiers which included Malays defected to the Kandyan side. Disease also ravaged the British. The Kandyans counter-attacked in March 1803 and seized Senkadagala. Barbut was taken prisoner and executed, and the British garrison wiped out; only one man, Corporal George Barnsley survived to tell the tale. The British unable to unable to withstand the Kandyan attack retreated. The British forces were defeated on the banks of the flooding Mahaveli river, leaving only four survivors. Kandyans did not stop with that. Their army, equipped with a handful of captured six-pound cannons, advanced through the mountain passes to Hanwella, a border town, but was routed by superior British firepower. North maintained pressure on the Kandyan frontier the next year, 1804, with numerous attacks. He dispatched a force under Captain Arthur Johnson towards Senkadagala which was also defeated. The appointment of General Thomas Maitland as governor of Ceylon in 1805 brought a temporary end to the military pressure on the Kandyan Kingdom.

The second Kandyan war took place in 1815. During those ten years (1805 -1815) two different processes took place in the British-controlled areas and in the Kandyan Kingdom. In the British administered areas Governor Thomas Maitland consolidated British power and influence through a series of reforms and by bringing more Europeans into the country, Maitland restructured the civil service and eliminated corruption. He created a Ceylonese High Court based on caste law. He enfranchised the Catholic population and withdrew the privileged position granted to the Dutch Reformed church. Maitland also undermined the Buddhist authority. He brought Europeans into the island by giving them large extents of land. Sir Robert Brownrigg who succeeded him in 1812 largely continued these policies. Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe, on the other hand, created a situation that led to instability in Kandy. He executed Pilimatalawe and tortured and killed the members of his family which turned out to be very unpopular among the Kandyan nobles. He also antagonized the Mahanayakes through arbitrary requisitions of land and treasure. The British made use of this discontent to overthrow the king. The role played by John D'Oyly, a British civil servant, in the overthrow of the Nayakar monarchy was significant. The events connected with the Second Kandyan war and the Kandyan Convention had been given in the last chapter. The British honouring the undertaking they gave the Kandyan chiefs administrated the Kandyan areas as a separate unit. Thus in 1815 Sri Lanka was administered as three units: Kotte. Jaffna and Kandy. That continued till 1833. A change was made in that arrangement in 1833 as a consequence of the 1818 revolt. The Kandyans revolted in 1818 because they realized that the British were in no way better than the Nayakar kings. Discontent with British activities soon boiled over into open rebellion in Uva and Wellassa. Hence the rebellion is usually referred to as the Uva Rebellion or Wellassa Rebellion. The revolt was Sri Lanka’s first struggle for Independence from British rule. It is also known as the “Great Rebellion of 1818”. The Kandyans were greatly affected by the administrative policies of the British and were not used to being ruled by a king who lived far away in another continent. This created unrest among the local people and the aristocratic Chiefs in the Kandyan Kingdom. The rebellion was led by Wilbawe, an alias of Duraisamy, a Nayakar of Royal blood, and Keppetipola Disawe. Keppetipola was sent by the British to stop the uprising. Most of the Kandyan chiefs joined the rebellion. The rebels captured Matale and Kandy before Keppetipola fell ill and was captured and beheaded by the British. His skull was abnormal - as it was wider than usual - and was sent to Britain for testing. It was returned to Sri Lanka after independence, and now rests in the Kandiyan Museum. The rebellion failed due to a number of reasons. It was not well planned. The areas controlled by the Chiefs who helped the British provided easy routes to transport food and other necessities. Doraisami [Duraisamy], one of the leaders, did not have many followers. The British suppressed the rebellion by arresting and executing the rebels through 'Search and Destroy' operations. Houses, property, livestock and even the salt in their possession were destroyed. The irrigation systems in Uva and Wellassa were also systematically destroyed. Herbert White, a British Government Agent in Badulla minuted in the 'Journal of Uva':

The British blamed Ehelepola for the revolt. He was arrested, taken to Colombo and exiled to Mauritius, where he died in 1829. Unification of Sri Lanka According to K.M. de Silva in The History of Ceylon, “Thus the year 1818 marks a real turning point in the history of Sri Lanka”. The British became the masters of the entire island. The whole of Sri Lanka had not been under a single ruler after the days of Parakramabahu I and Vijayabahi I. Though Kotte King Parakramabahi VI claimed the control of the entire country his supremacy lasted for only 17 years when Sapumal Kumaraya ruled Jaffna. Even Parakramabahu I and Vijayabahu I did not try to bring about the unification of the administration of the entire country. The British who wanted to prevent rebellions in the future started a process of unifying the administration of the country while abolishing or reducing the privileges of the nobles. The two governors who succeeded Brownrigg who retired on February 1,1820 – Edward Paget (February 1812 –November 1822) and Edward Barnes (January 1824- October 1831) continued Brownrigg’s policy of unification of the country. They adopted the following measures to achieve their objective:

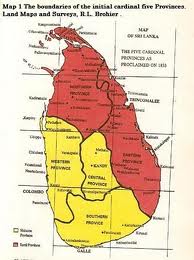

All these measures taken together started the process of the unification of the country. Yet they administered Kotte, Jaffna and Kandy as separate units. To complete the process of unification Governor Barnes requested the British Colonial Office to send a Royal Commission to look into the administration of the three units. The Unitary State King George IV appointed in April 1829 a Royal Commission headed by Major W M G Colebrooke to examine "all laws, regulations and usages of the settlements in the island and into every other matter in any way connected with the administration of the civil government". Colebrooke was followed by Charles Hay Cameron, who was commissioned to report on the judiciary. The commissioners presented their recommendations in 1832, suggesting the creation of one government with one centralized, unitary form of administration under a governor in Colombo. The British did this without the consent of the people, and in doing so ended the hopes for a Tamil or a Kandyan nation as a distinct political entity, something that no conqueror had managed to do throughout the history of Sri Lanka. The Colebrooke commissioners also recommended that the Island should be divided into five provinces - Colombo, Kandy, Galle, Jaffna and Trincomalee. They further recommended the establishment of Executive and Legislative Councils. This uniform administrative structure and the idea of a "united Ceylon" spelt doom for the Tamils' distinctiveness which Sinhalese rulers had failed to achieve. There were periods when Sinhalese kings ruled the whole of Sri Lanka. Under the monarchical system that prevailed during those times what they achieved was supremacy of the entire country by making the other rulers their tributaries. They never imposed their administration in the territories they brought under their control.

The Colebrooke Commission by introducing the unitary form of government changed the political structure of Sri Lanka. C.G. Mendis has recognized this fact in his book Early History of Ceylon. He considers the Colebrooke reforms to be the dividing line between the past and present Sri Lanka. Five Provinces As noted above the Colebrooke commissioners recommended that the Island should be divided into five provinces - Colombo, Kandy, Galle, Jaffna and Trincomalee. The demarcation of the five provinces was done through the proclamation of September 30, 1833. When the British East India Company took over the administration of the maritime territories from the Dutch it placed them under the Madras Presidency. When Sri Lanka was declared a Crown Colony in 1802 the government reverted to the system of administration adopted by the Dutch which closely resembled the native authority structures and divisions of earlier times. The British officials divided the maritime areas into what they called collectorates, which were: Colombo, Kalutara, Galle, Matara, Negambo. Chilaw, Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Vanni, Jaffna and Mannar. Subsequently the collectorates were abolished and the territory was divided into 13 provinces including those of Jaffna, Mullaitivu, Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Mannar. Following the recommendation of the Colebrooke Commission the 13 provinces were fused into five provinces through the proclamation issued by Governor Norton. In forming the five provinces British administrators took care to adhere to the existing political divisions. According to the Proclamation the territories of the Northern and Eastern Provinces were demarcated thus:

The territorial limits mentioned in the Proclamation depict the areas under the control of the Tamil people in 1833. In the subsequent years the number of the provinces were raised to nine and the main suffers were the Tamils. The sixth province called the North Western Province was created in 1845 by the annexation of territories from the Western and Central Provinces. In 1873 the North Central Province was constituted by bringing together Nuwarakakalaviya of the Northern Province, the seventh province, and Thambankaduwa of the Eastern Province and Demala Hatpattu of the North Westerrn Province. The provinces of Uva and Sabragamuva were formed in 1886 and 1889 bringing the number of provinces to nine. The Sinhala belief that the island of Sri Lanka belonged to them and the Tamil belief that they too have a similar claim was the basic cause of the Sinhala Tamil conflict. It was accentuated by the unitary state structure thrust on them by the British. Next week; Emergence of Nationalisms --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Index Emergence of Racial Consciousness Birth of a Unitary State |

|||||||

|

||||||||

A look at the definitions of the words monarchy, tributary and unitary state clearly indicates that Sri Lanka was never a unitary state. We have had monarchies and tributary states but never a unitary state. Whenever Jaffna was conquered by a Sinhalese king he never interfered with the local administration. Even in the case of Sapumal Kumaraya he did not disturb the existing administration. In a unitary state that is not so. A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as one single unit in which the central government is supreme and any administrative divisions (subnational units) exercise only powers that the central government chooses to delegate.

A look at the definitions of the words monarchy, tributary and unitary state clearly indicates that Sri Lanka was never a unitary state. We have had monarchies and tributary states but never a unitary state. Whenever Jaffna was conquered by a Sinhalese king he never interfered with the local administration. Even in the case of Sapumal Kumaraya he did not disturb the existing administration. In a unitary state that is not so. A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as one single unit in which the central government is supreme and any administrative divisions (subnational units) exercise only powers that the central government chooses to delegate.