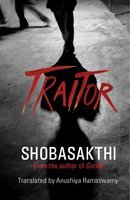

'Traitor'

by

Shobasakthi, translated by Anushiya Ramaswamy, Viking Penguin India, 2010

|

A stark rhetoric of torture, pain and black humour, Traitor, through its pathologically damaged protagonist, gives voice to the testimonies of millions of refugees of a war-ravaged land. |

Summary

‘As I live my days locked up in a wretched prison in this frozen country, I start to write the story of my beloved child, Nirami. The story begins with the birth of God.’

Nirami, Nesakumaran’s fourteen-year-old daughter, is awaiting her abortion in the hospital room of an unnamed European city; she refuses to name her rapist.

Nesakumaran’s narrative begins in 1980s Sri Lanka when, radicalized by the dream of Tamil Eelam, he abandons his seminary studies. A bungling terrorist, botching up one task after another, Nesakumaran is in no way a genuine threat. But once he has entered the system as a suspect he can never find a way out of the maze of interrogation chambers, army camps and regional prisons. What follows is a surreal account of torture, which culminates in the extremely brutal massacre of Tamil prisoners by the Sinhalese inmates in the Welikade prison in 1983, and also, the revelation of Nirami’s rapist.

A stark rhetoric of torture, pain and black humour, Traitor, through its pathologically damaged protagonist, gives voice to the testimonies of millions of refugees of a war-ravaged land.

Book review by Urooj Zia, Himal, August 2010

Shobasakthi, a former LTTE child soldier, gives a stark account of some of the most bloodcurdling moments in the history of what his protagonist, Nesakumaran, refers to throughout as ‘the Movement’. The story begins with Nesakumaran in exile in the US, but quickly we go back to his years in the ‘Movement’. Throughout the narrative, Nesakumaran is neither ‘heroic’ nor superhuman – he gives in to tears and pleads with his Sinhalese tormentors when threatened with sexual humiliation. But he also survives, and in order to do so, the preyed-upon often becomes party to the predation. Every school of thought within ‘the Movement’ is examined – from the raw anger of ‘goons’ to the non-violence of the benign, intellectually inclined Pakkiri, who ‘gently pushes the gun barrel away from his face’ just before his Tamil tormentors ‘tear open his mouth and beat him to death with their bare hands’. Yet his characters are neither saints nor demons – the war is never depicted as one between good and evil.

Book review: Sri Lanka’s civil war up close & personal

By Deepak Narayanan, Mumbai, Daily News & Analysis India, Sunday, Jun 6, 2010

Shobasakthi’s second novel, Traitor, narrates the story of Nesakumaran, the only boy in the Tamil-dominated Palmyra Palm Island — off Sri Lanka’s northern coast — who’s studying to become a priest. He, however, ends up as a child soldier for the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE) instead.

The story of Traitor is also the story of the beginning of the full-scale Civil War in the 1980s that was to tear Sri Lanka apart for the next 30 years. At the centre of the entire narrative is a gut-wrenchingrendering of a real event: the Welikade Prison massacres of July, 1983, in which 53 Tamil prisoners — most of them held without trial under the Prevention of Terrorism Act — were massacred in the walled-off complex by Sinhalese convicts given license to kill by the cops who were supposed to be guarding them.

“When I climbed up to the window and looked out again, I saw the prisoners in B3 being dragged out into the common hall and cut to pieces…” says Nesakumaran, describing in graphic detail the events of that day. “Mannikadasan, who was watching from his cell window, said that they were piling up the corpses in front of the Buddhist temple near the entrance of the prison.” While Sobhasakthi’s fictional account is drawn from conversations with the survivors, till date, in the real world, no charges have been filed in the case.

While Sobhasakthi’s method — using a micro-story to comment on the big picture — isn’t exactly novel, what makes Traitor special is the trickiness of the subject. Himself a Lankan Tamil refugee (now living in France) and a former LTTE child soldier, his stand on the conflict is never in doubt, and a fair percentage of the 231 pages are spent on inter-twining accounts of police and army brutality. At all times, the line between reality and fiction stays blurred. For example, there’s the story of Shanmuganathan, who Nesakumaran says was arrested in 1986 along with 62 other Tamils:

“When the target practice began, Shanmuganathan and the other prisoners were made to take the place of the usual dummies of hay. At that morning practice, forty-one soldiers were able to shoot their targets accurately. Twenty-two missed. Shanmuganathan was shot in the leg. Another twenty lay on the ground half-dead.” Finally free 16 years later, Shanmuganathan has already been declared dead by the government. He’s bruised, battered, crippled, but his most pressing worry is “to prove to the government that I am alive.”

Thanks to its disturbingly flawed protagonist, Nesakumaran, Traitor avoids ending up as a self-piteous rant. Far from being heroic, Nesakumaran snitches every time he’s threatened with torture, pawning the lives of close friends for his own meaningless existence. Nesakumaran’s vulnerability adds conviction to the narrative, and his journey, though never pleasant, is brutally honest and worth a read.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives Home

Home Archives

Archives