Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lankan Tamil StruggleChapter 14: Clash between Nationalisms Intensifiesby T. Sabaratnam

Aryan – Dravidian Divide The clash between the Sinhala- Buddhist and Tamil Nationalisms intensified from the beginning of the 20th Century. Greater number of Sinhala and Tamil children had taken to education by that time and the clamour for government jobs and entry into the professional courses of study had begun. That posed greater challenge to the Tamils who were almost dominating the clerical service and the prestigious professions. Education Department statistics reveal that about 25 percent of the children of school-going age attended school in 1901. The rush to join the medical, law and technical colleges had increased. Charges that Jaffna students were gaining admission to the professional courses in greater numbers was also voiced by Sinhala nationalists. The sudden rise in the Indian Tamil population had reawakened the traditional Sinhala fear of Tamil domination. With the introduction of tea cultivation in 1867 and rubber planting in 1877the migrant Indian Tamils began to settle down in their estates as tea and rubber needed resident labour. Thus the Indian Tamil labour which was 123,000 in 1870 rose to 195,000 in 1881 and to 235,000 in 1891. The emerging Sinhala commercial sector, especially the retail trade, began to grumble that Tamils and the Muslims were standing in their way to prosperity. Tamils and Muslims who controlled the textile and food commodity trade had also built a network of retail shops across the country. The impact of these socio-economic changes intensified the clash that had begun in the last quarter of the previous century. Two of the British government’s policies, the acquisition of land in the Kandyan districts for plantation companies and the excise policy of licensing taverns for sale of arrack and toddy had activated the Kandyans and the Low Country Sinhalese about their rights.

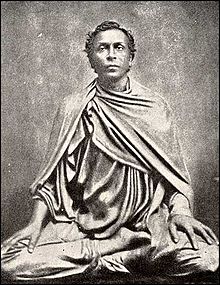

By the beginning of the 20th century, Sinhala- Buddhist nationalism had begun to lose its anti- Christian character and had begun to acquire an anti- Tamil complexion. Tamil nationalism, on the other hand, as already pointed out had acquired a linguistic character. Anakarika Dharmapala played the prominent role in giving the Sinhala- Buddhist nationalism an anti- Tamil character. Tamils who had welcomed the transformation of the Sinhala- Buddhist nationalism into an anti-colonial movement were disturbed when Anagarika Dharmapala gave it an anti- Tamil twist. By the beginning of the 20th Century Tamils noticed with disquiet that Sinhala- Buddhist nationalism was acquiring a Sinhala- Buddhist orientation and an anti- Tamil, anti- Muslim character. Dharmapala, (September 17, 1864 – April 29, 1933) the son of H. Don Carolis, a prominent furniture manufacturer in Colombo was named Don David Hewavitarne at birth. He was educated in Christian schools. He started his schooling at CMS Boy’s School which later became Christian College, Kotte. Then he studied at St. Benedict College, Kotehena, St. Thomas” College, Mount Lavania and ended up at Royal College, Colombo. His parents were among the richest merchants of Ceylon. His younger brother was Dr. Charles Alwis Hewavitharana. This was a time of Buddhist revival. From youth Dharmapala took up Buddhist promotion work. He became the interpreter to Olcott soon after he arrived in 1880. He toured the Sinhala areas with Olcott and changed his name to Anagarika Dharmapala. Dharmapala' means protector of the dharma'. 'Anagarika', a term coined by Dharmapala, means "homeless one." It is a midway status between monk and layperson. Dharmapala was the first anagarika - that is, a celibate, full-time worker for Buddhism. Although he wore a yellow robe, it was not of the traditional bhikkhu pattern, and he did not shave his head. His trip to Bodh-Gaya was inspired by an 1885 visit there by Sir Edwin Arnold, author of The Light of Asia, who soon started advocating the renovation of the site and its return to Buddhist care. Dharmapala eventually broke with Olcott and the Theosophists because of Olcott's stance on universal religion. "One of the important factors in his rejection of theosophy centered on this issue of universalism; the price of Buddhism being assimilated into a non-Buddhist model of truth was ultimately too high for him." Dharmapala founded the Maha Bodhi Society in 1891 and published the 'Mahabodhi Journal' and the 'Sinhala Bauddhaya' in the 1910s. He turned Buddhist nationalism into an anti-Tamil and anti-Muslim movement. In doing that he was influenced by the discovery of the Buddhist Pali chronicle, the Mahavamsa, by Turnour, a British civil servant, and its translation by him into English in the 1830s and the identification of the Sinhalese as an Aryan language by a section of linguistic scholars Delivering a speech in India Dharmapala proclaimed that Sinhalese were the original inhabitants of Sri Lanka and declared the Tamils and Muslims were invaders and interlopers. Claiming Mahawamsa as his authority he declared that the Sinhalese had defeated and expelled the Tamils whenever they invaded Sri Lanka. He cited the Mahawamsa story of the defeat of Ellara by Dutthugamani to prove his point. Dharmapala was a dynamic orator and attracted a large following among the middle class and in villages. He preached that Sinhalese - the Lion Race - were a superior people as they descended from pure Aryan stock. Basing his claim on the Mahawamsa he wrote,

In 1902, Dharmapala wrote,

By polytheism Dharmapala meant Hinduism. He also pointed to the past glories of the Sinhalese civilization as portrayed by the Mahavamsa as a way of infusing the Sinhalese with a nationalist identity and self-respect in the face of the humiliation imposed by the British rule and Christian missionary activities. Once he struck the nationalist note he blasted everything foreign. He attacked the Anglicized and Christianized Sinhalese elite and ridiculed them for their Westernized life, foreign dress and European names (such as Perera, Silva, Diaz, Cabral, Gomez). Finally, he turned to the Tamils, Muslims and other non Buddhists in the island. He wrote:

Through his propaganda he created a new Sinhala- Buddhist identity which rested on: Sri Lanka is the land of Theravada Buddhism because Buddha blessed it to be so during his three visits; Sri Lanka is the land of the Aryan Sinhalese because Vijaya established the first human settlement and that Tamils, Muslims and others (Hindus, Islamists and Christians) were foreigners and invaders who polluted the pristine Buddhism. Dharmapala ended up as a racist. He roused the Sinhalese saying that the Sinhalese should rule the Sinhala country, for only then they could restore the ultimate fairness and justice with their Buddhist philosophy. In 1911 he wrote,

Dharmapala took control of the Temperance Movement by the end of the 19th Century and made use of it to whip up national spirit of Sinhala Buddhists. He turned the movement into an anti- Karava, anti- Tamil and anti- Christian campaign. He founded the Sura Virodhi Vyaparaya , an organization against alcoholism, in 1895. Temperance movement Temperance Movement was introduced into the Jaffna peninsula long before Dharmapala founded his society. American Ceylon Mission introduced temperance into Jaffna during the 1830s. The batch of American missionary teachers who joined the Batticotta Seminary during that period were teetotalers and their refusal to drink alcohol prompted Poor, the principal, to stop serving drinks at parties. He also launched a campaign against the evil of the drinking habit. In one of the articles he wrote for the Morning Star he said,

From Poor’s comments we can infer that the toddy and alcohol drinking habit had become widespread in the Jaffna peninsula during his time. Similar situation prevailed in the Sinhala areas too. Records available with the Excise Department show that taverns were opened in almost all the villages in the country.

Wesleyan Mission in Jaffna also organized a Temperance Movement in 1834. It was an umbrella organization that brought together all the temperance societies in the peninsula. A delegation of the World Conference of Temperance Unions (WCTU) visited Jaffna during this period. The tavern system for the selling of alcohol and toddy was introduced in 1820 by Governor Barnes as a revenue raising measure. The Excise Department issued permits to open liquor shops and the permits were sold by auction thus maximizing the government income. In 1820 itself one percent of Sri Lanka’s population had become alcoholics and the government earned 60,000 sterling pounds. An entry in the diary of J. Forbes, a District Judge, provides a glimpse of the seriousness of the situation. He wrote that 133 taverns were opened in an area where 200,000 residents lived. The tavern system not only made alcohol drinking popular but also created among the Low Country Sinhalese severe social problems. The tavern renters were mainly from the Karava (fishermen) caste and they became very rich. By 1864 the De Soysa family became the wealthiest in Sri Lanka. It amassed its wealth through arrack sales and through investment in coconut plantations. From then on the Karawa business community which was faithful to the British rulers posed a challenge to the Govigama nobles. Opposition to the tavern system was voiced in 1820 itself. A British army officer Lt. Thomas Skinner in his memorandum submitted to Governor Barnes said,

Skinner raised his objection because he was under the influence of the temperance movement which was popular in Britain, America, Australia, New Zealand and many colonial countries. World’s first temperance society was formed in Connecticut, America. A group of about 200 farmers influenced by the writings of Dr. Benjamin Rush who maintained that excessive use of alcohol was injurious to physical and psychological health formed an association in 1789 and campaigned for the ban of manufacture of whiskey. Similar temperance societies were formed in Virginia in 1800 and new York in 1808. The movement spread and The American Temperance Society was formed in 1826. Within the next 12 years more than 8,000 local groups with over 1,500,000 members were formed nationwide. Christian clergy took the lead in spreading the message. The American missionaries who joined the Batticotta Seminary in 1830’s belonged to the groups that advocated temperance. At their insistance American missions in the Jaffna peninsula formed temperance units in all their stations. American Mission Report 1845-1854 says that temperance movements were in existence in all the mission stations in the Jaffna peninsula and in the outstation stations. Newspapers of that period Morning Star and Uthaya Tharakai had provided coverage for the formation of temperance societies and the spread of the movement. The following item in the Morning Star indicates that the movement had seeped down to the student level. It reads,

The Morning Star has also reported the formation of temperance movements in several parts of the Jaffna peninsula during 1850 and 1851. The paper has published reports of the formation of Temperance Societies in Manipay, Tellipalai, Chavakachcheri, Kayts, Atchuveli, Karaveddi and Uduvil. From these reports it is clear that the opposition to the drinking habit and liquor trade was widespread in the Jaffna peninsula. Uthaya Tharakai conducted a vigorous campaign against the renting of toddy and arrack taverns. In the second half of the 19th Century the temperance movement was an integral part of the Saiva revival movement. Though at times anti- government overtones were noticeable the campaign never took anti- Christian or political dimensions. It was purely an attack on the drinking habit and the disruption it caused in the family and society. Navalar had concentrated his attention on the evils of alcoholism in his pirasangams. He adopted a positive approach and dwelt mainly on the virtue of abstaining from alcohol. After Navalar’s death and following the transformation of the religious revivalism into a Tamil linguistic nationalism interest in the temperance movement declined in the Jaffna peninsula and the drinking habit surged. The rising trend of alcohol and toddy consumption is revealed by these figures: The revenue collected by the government in the northern province from arrack and toddy was Rs.13,448 in 1895 and Rs. 20,000 in 1896. This perturbed the religious and social activists of Jaffna who were watching with appreciation the growth of the temperance movement in the south. They revived the temperance movement and in mid-1920s, during the active days of the Jaffna Youth Congress and when Mahatma Gandhi visited in 1928 Jaffna had achieved total prohibition. In the south too the Christian missionaries launched a campaign against drinking during the last quarter of the 19th century. Buddhists joined it and by the beginning of the 20th century they took over the leadership. Dharmapala who led the Buddhist revival movement preached that alcoholism was a tool of Westernization and Christianization. His followers overstepped their limit occasionally and criticized Christians thus giving it an anti- Christian orientation. The influence of the temperance movement peaked in the south and the north during 1904-1905 and its tempo slowed down following the departure of Dharmapala to India. It revived in 1912 when the Colonial Government issued a decree permitting the opening of taverns in every village and town. Opposition to that order was almost island wide. In Colombo Anagarika revived the temperance movement. P.A. de Silva of Bandarawatte, Koggala provided the leadership in the South. Jaffna College teachers and students were drawn into the movement. Several interesting anecdotes are available about this campaign. Martinus C. Perera was a well-known businessman from Colombo. He would go from place to place on his bicycle carrying a violin. He would stop at places when he saw a crowd. He would play the violin and dance. After sufficient people gathered he would deliver his oration on the evils of drinking. The temperance movement received a major boost with the arrival in Sri Lanka of ‘Pussyfoot’ Johnson, an American temperance worker. He organized temperance meetings in various parts of the island and one of those was held at Ananda College, Colombo. The meeting was chaired by F.R. Senanayake, elder brother of D.S. Senanayake. After Johnson delivered a stirring speech on the evils of liquor a man in the audience stood up and started to scoff at the temperance movement saying that it would serve no useful purpose. He was R.L. Pereira who later became a leading lawyer and King’s Counsel . But the majority in the audience did not allow him to continue with his speech. He was compelled to stop half-way when he was jeered and hooted at. On another occasion at a meeting in Mirigama, a person stood up and challenged F.R. Senanayake who was in the chair. The man asked him, “When we don’t care for the advice of even Jesus Christ, Lord Buddha and Prophet Mohamed against drinking, would we care to listen to you?” He received the answer not from the chair but from members the audience. They thrashed him well and truly. In Jaffna a public meeting was organized to welcome Johnson. Kanagasabhai presided. A section of the audience, carefully planted by tavern renters, shouted slogans highlighting the impracticability of the temperance movement. A group of students caught the disrupters and took them to the platform and kept them standing till the meeting concluded. Instances of physical violence were recorded in the south and the north. Militant agitators waited in hiding near taverns and assaulted those who patronized them. Buddhists when caught drinking were forced to carry sacks of sand needed for repairs to temple buildings. In some places drinkers were given ‘welcome’ with garlands made of coconut shells! Coconut shells because toddy was served in taverns in coconut shells. Jaffna newspapers have recorded instances where alcoholics were paraded round the village carrying earthen pots full of toddy. Temperance workers forced the government to accept a scheme of holding polls in Village Headmen divisions to determine whether to close the tavern in the area or not. Temperance Movement formed societies at village level to campaign for the closure of the tavern. In some villages sensing the mood of the people the village headmen joined them. The government reacted by issuing an order to the headmen prohibiting them from joining the societies. Other government officials were told to obtain permission from higher officials before joining the societies. These orders divorced the rural level government officials from the people. The temperance movement, when considered on the basis of the entire country, radicalized the people and created an environment suitable for political agitations. In the north, it paved the way for the formation of the Jaffna Association and assisted the intellectuals and students to think in terms of economic development of the region. In the south it created the condition for non- Panditharatna families, particularly the Senanayake family, to enter politics. Don Spator Senanayake who had made his fortune in plumbago among other things made his name through the temperance movement and his sons F.R., D.S. and D.E. entered politics through it. F.R. emerged as the lieutenant of Dharmapala and led a virulent racial campaign against the Tamils and the Muslims which created the environment for the 1915 riots. D.B. Jayatilleke was another prominent leader who entered politics through the temperance movement. Dravidian self-consciousness We have pointed out in Chapters 11 and 12 that Dravidian self-consciousness had emerged among the Tamil people in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu by the end of the 19th Century. In Sri Lanka it emerged as a response to Dharmapala’s claim that the Sinhalese were of Aryan origin and thus superior to the Tamils. In Tamil Nadu it emerged as a reaction to the dominance of the Brahmins who were of Aryan descent. Bishop Robert Caldwell’s (1814- 1891) publication, ‘Comparative Grammar of Dravidian Languages’ which appeared in 1856 had set in motion a train of ideas that influenced the thinking of the Tamil people. Caldwell held that Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada formed a separate language family which he named Dravidian languages. He also held that Tamil was the foremost language in the family. He said that Tamil possessed rich literature and had had an independent existence free of Sanskrit influence.

Sangam literature discovered and published subsequently proved Caldwell correct and gave a vital stimulus to the revival of the Tamil people and their nationalism and the emergence of Dravidian self- consciousness. Tamils found themselves equal if not a superior to the Sinhalese. The publication of the historical work ‘Tamil- Eighteen Hundred Years Ago’. by Jaffna scholar V. Kanagasabaipillai (1855-1906), who served in Madras University gave additional pride to the Tamils. In that publication which appeared in January 16, 1904 Kanagasabaipillai showed that the entire Indian subcontinent was ruled by non-Aryan tribes 1800 years ago. He showed that at that time the southernmost portion of India formed Thamilakam, the land of the Tamils. He said the discovery of Sangam literature had proved the Western scholars who said that Tamil had no literature before the 9th Century AD were wrong. Kanagasabaipillai’s work generated a new enthusiasm and pride among the Tamil people and in the first decade of the 20th century Tamil nationalism peaked. It had shed major part of its religious character. In Sri Lanka, Saivaites were willing to work with the Christians to face Dharmapala’s challenge. In Tamil Nadu Hindus and Christians joined hands to break the Brahmin domination. Political Leadership The socio- economic changes that took place among the Sinhala and Tamil communities, especially the emergence of Sinhala- Buddhist and Tamil nationalisms that grew during the second half of the 19th Century were not reflected by the political leadership of the Sinhala and Tamil leadership. That was because the leaderships of both communities did not emerge from the people. They were imposed from above by the British rulers. The representative system was the result of a recommendation by the Colebrooke Commission, which recommended an Executive Council and a Legislative Council to assist the Governor. The Executive Council comprised five members. They were: the Commander of the Forces, the Colonial Secretary, the King’s Advocate, the Colonial Treasurer and the Government Agent of the Central Province. The Legislative Council consisted of nine officials and six unofficial members nominated by the Governor. The nine officials were: the Chief Justice, an officer commanding the land forces, the Colonial Secretary, the Auditor General, the Colonial Treasurer, the Government Agent for the Western Province, the Surveyor General and the Collector of Customs at Colombo. The six unofficial members were: three Europeans and one each to represent the Sinhalese, Tamils and Burghers. The criteria stipulated for nominations were: for Europeans- respectable merchants or residents; for others- high class indigenous people. The choice for the Sinhala representative fell on G. Philipsz Panditharatna, a Govigama Anglican Christian and a wealthy landowner. Arumuganathapillai Coomaraswamy, a Vellala Hindu, was nominated as the Tamil representative. Members of the families of those two nominees provided the political leadership of the two communities for nearly a century. J.G. Hillebrandt was nominated as the Burgher member. Panditaratne was succeeded by his sister’s two sons, J. C. Dias Bandaranaike and H. Dias Bandaranaike, the younger brothers of Rev. S. W. Dias Bandaranaike who later became a Canon of the Anglican Church, Colonial Chaplain and Vicar of All Saints’ Church, Hulftsdorp. J. C. Dias Bandaranaike was enrolled a Proctor in 1839 and was a Member of the Legislative Council till 1861. He was succeeded by H. Dias Bandaranaike who was the first Sinhalese to be called to the Bar in England and the first such to be appointed a Judge of the Supreme Court (1879) and knighted. He was succeeded by Philipsz Panditaratne’s grand nephew, Advocate James D’ Alwis in 1864. D'Alwis was also a great Oriental Scholar whose contributions to the development of the Sinhala language and literature earned him a place in recent history. Another of James D’ Alwis’ relatives, Albert L.D.’ Alwis was also an Unofficial Member of the Legislative Council. While Panditharatna’s family provided the Sinhala political leadership Coomaraswamy’s family dominated the Tamil political scene. Panditharatna and his family members were Anglican Christians who had adopted the Western way of life while Coomaraswamy and his family members were practicing orthodox Saivaites. They never gave up their Saivaite way of life. Though both families collaborated with the British government Coomaraswamy family’s outlook was more responsive to the aspirations of the local people, the Tamils and the Sinhalese. Panditharatna’s family, in most instances, reflected the interests of the British rulers and the Christian Church. Coomaraswamy (1783-1836) was from Garudavil, a village near Point Pedro. His father Arumuganathar Pillai was an immigrant from Tamil Nadu who came and settled in Garudavil. The family moved to Chekku Street, Colombo at the turn of the 19th Century. He was educated at The Academy (now Royal College) and was appointed Mudaliyar of the Governor’s Gate which gave him the opportunity to move closely with the governors. From 1808, Coomaraswamy served as an interpreter to Governor Thomas Maitland and rose to the position of Governor’s Chief Interpreter. He was nominated as an unofficial member of the Legislative Council to represent the Tamils in April 1833. A British publication London News said that he was nominated to the Legislative Council due to his high status and as a reward for the services he had rendered to the British government. The report published by the paper said,

Coomaraswamy was an unabashed collaborator and admirer of British rule. This servile devotion of Coomaraswamy is an important factor that must be taken note of to evaluate the role his successors played for nearly a century, 1833- 1930, the period that ended with he death of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan. Coomaraswamy family’s slavish devotion to the unitary state created by the Colebrooke Commission led Ramanathan to the ridiculous situation of opposing the granting of adult suffrage. Coomaraswamy died on November 7, 1836 and was succeeded on the Council by Mudaliyar Simon Cassie Chetty (1807- 1860) a Roman Catholic from Puttalam. (Next week; Tamils Demand Communal Representation) Index Chapter 2: Origins of Racial Conflict Chapter 3: Emergence of Racial Consciousness Chapter 4: Birth of the Tamil State Chapter 5: Tamils Lose Sovereignty Chapter 6: Birth of a Unitary State Chapter 7: Emergence of Nationalisms Chapter 8: Growth of Nationalisms Chapter 10: Parallel Growth of Nationalisms Chapter 11: Consolidation of Nationalisms Chapter 12: Consolidation of Nationalisms (Part 2) Chapter 13: Clash of Nationalisms Chapter 14: Clash between Nationalism Intensifies Chapter 15: Tamils Demand Communal Representation |

|||||||

|

||||||||