Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by Sachi Sri Kantha, November 1, 2010

|

October 30th marked the eleventh death anniversary of Saumiyamoorthy Thondaman (1913-1999), the legendary Indian Tamil politician and trade union activist. |

I have read that there is a book with the title, The American Directory of Certified Uncle Toms (1999). Some prominent names included in this book, in alphabetical order, are Bill Cosby, Colin Powell, Condolezza Rice, Clarence Thomas, Oprah Winfrey and Tiger Woods. The phrase ‘Uncle Tom’, derived from a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) novel, is a servile black man who dances to the wishes of whites.

Suppose, if one has to prepare a similar version, ‘The Sri Lankan Directory of Certified Uncle Toms’, the most prominent names that have to be included in it were the Tamil Cabinet ministers, since independence – the likes of C. Suntheralingam, C. Sittampalam, G.G. Ponnambalam Sr, V. Nalliah, S. Natesan, Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan, M. Tiruchelvam, C. Kumarasuriar, K.W. Devanayagam, S. Thondaman, C. Rajadurai, L. Kadirgamar, D. Devananda and V. Muralitharan (aka Karuna). But, in any logical sense, it is unfair that the standing of Thondaman, Sr. (who had fought and defended the Tamil rights for 30 years, before he became a cabinet minister) to be equated with that of Lakshman Kadirgamar, a Johnny-come-lately. As such, I suggest an Uncle Tom Index (UTI): the higher the acceptance by the Sinhalese the less credibility one has among the Tamils or vice versa. In my estimation, whereas Kadirgamar’s UTI is the highest, Thondaman’s UTI is the lowest.

October 30th marked the eleventh death anniversary of Saumiyamoorthy Thondaman (1913-1999), the legendary Indian Tamil politician and trade union activist. I have long been an admirer of Thondaman’s career, for more than one reason. First, unlike other Tamil Cabinet Ministers whom I’ve named above, his UTI is lowest among Tamils. Secondly, he had been taunted, ridiculed and for many decades for his convictions, by the Sinhala racists. Thirdly, he was a gentleman; whatever the differences he had with the Eelam Tamil leaders (Ponnambalam, Chelvanayakam, Amirthalingam and Prabhakaran), he never identified with the Sinhalese politicians to call names publicly, for his political survival. Fourthly, he cared to write his autobiography and record his first hand experiences with the Sinhalese political leaders.

Four years after its publication in 1994, I was able to receive a copy of the 2nd volume of Thondaman’s autobiography ‘My Life and Times’. This is an unusual document, in the history of Eelam Tamil literature. I’m under the impression that, Thondaman wouldn’t have had the time to literally ‘write’ his version of history. Until 1999, he was active (even at the age of 86), holding a cabinet minister position. Maybe, (1) he might have recorded his thoughts in a cassette recorder at occasions, and someone would have transcribed the oral records into script. (2) the autobiography was ‘ghost written’. No mention (acknowledgment) is made about who this ghost writer was. In fact, there was no acknowledgment section in the book itself.

The book has a foreword by Prof. Ralph Buultjens, which provides a synopsis of the career of Thondaman’s enterprising father Karuppiah Thondaman (died in 1940), soon after his youngest son Mathavan (born in 1913 in Munapudur village, Pudukkottai district, Tamil Nadu), later to be known as Saumiamoorthy Thondaman, himself made his entry in labor activism in colonial Ceylon, after landing in the island in 1924.

In the Introductory Prologue, Thondaman mentions,

“In Volume One, I was mainly concerned with the background situation and the milieu in the plantations in which my father had worked and I had grown up. I had also briefly touched on some aspects of my trade union and political work. Admittedly, volume one had much more about the ‘Times’ and comparatively little about ‘My Life’. But, without the backdrop of the ‘Times’ I felt the story of ‘My Life’ could not be understood in its proper setting.

In this Volume, I will deal more exhaustively with ‘My Life,’ setting out wherever possible my personal recollections about men and matters from around the year 1939 when I was drawn actively into the political arena in this country…”

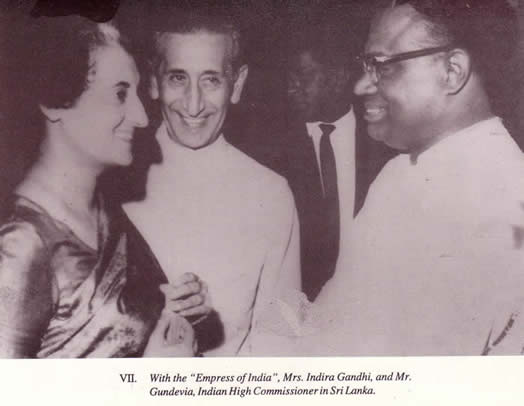

Though the written text may have been marginally ‘decorated’ by a ghost writer, I had a feeling that the captions provided to the chosen 15 photographs were characteristic of the autobiographer’s preferences. [For record, I provide scans of two photographs, in which Thondaman appears with Indira Gandhi and MGR.] In the 15 selected photos included in the book, Thondaman had touched all ‘political bases’, including that of JVP. Photos of Rohana Wijeweera and that of G.G.(Kumar) Ponnambalam appear in the book, though Thondaman was not included in these. Notable omissions include that of any Federal Party leaders and that of Sirimavo Bandaranaike. One cartoon of Thondaman by cartoonist Wijesoma also appears in the book.

Due to his half a century longevity in political arena, Thondaman would remain as one of the two politicians in the island (the other one being, J.R. Jayewardene) to have had the opportunity to interact with three generations of Nehrus (Jawaharlal, his daughter Indira and his grandson Rajiv). I should record, Thondaman’s one act here, which was detrimental to LTTE and Eelam Tamils in 1989. If not for Thondaman’s behind the scene peace-making deals with Rajiv Gandhi, on behalf of belligerent President Premadasa, in July 1989 (in the aftermath of assassination of A. Amirthalingam, which I consider as RAW-induced, as Premadasa himself should have been aware of), Sri Lankan army could have clashed with IPKF stationed in the island. Reading between the lines of the highly-censored news reports from Colombo of that period and T. Sabaratnam’s biography on Thondaman is of relevance here. (See below, for the cited sources) Some Premadasa apologists may be inclined to deny this now, but the events of July 1989 studied in depth record the serious role Thondaman played in averting Indo-Sri Lankan military conflict.

Due to his half a century longevity in political arena, Thondaman would remain as one of the two politicians in the island (the other one being, J.R. Jayewardene) to have had the opportunity to interact with three generations of Nehrus (Jawaharlal, his daughter Indira and his grandson Rajiv). I should record, Thondaman’s one act here, which was detrimental to LTTE and Eelam Tamils in 1989. If not for Thondaman’s behind the scene peace-making deals with Rajiv Gandhi, on behalf of belligerent President Premadasa, in July 1989 (in the aftermath of assassination of A. Amirthalingam, which I consider as RAW-induced, as Premadasa himself should have been aware of), Sri Lankan army could have clashed with IPKF stationed in the island. Reading between the lines of the highly-censored news reports from Colombo of that period and T. Sabaratnam’s biography on Thondaman is of relevance here. (See below, for the cited sources) Some Premadasa apologists may be inclined to deny this now, but the events of July 1989 studied in depth record the serious role Thondaman played in averting Indo-Sri Lankan military conflict.

In this tribute to Thondaman’s memory, I wish to highlight specific segments of his autobiography, relating to the two prime ministerial tenures of Sirimavo Bandaranaike. I consider his observations are worthy of record.

Thondaman on the Two Tenures of Sirimavo Bandaranaike

[Notes by Sachi: Abbreviations used in the text are, CWC = Ceylon Workers Congress, EPF =employee provident fund, LRC= Land Reform Commission, UF= United Front. Dots in the excerpts usually indicate omissions made by me. Wherever dots appear in the original, I indicate that specifically at the end of that particular sentence, with a note to that effect. Words within parenthesis, are as in the original.]

SLFP Period (1960-64)

Mrs. Bandaranaike was sworn in as Prime Minister on July 22, 1960 and formed an all-SLFP government. After much discussion in the SLFP leadership I was appointed a Nominated MP on August 4th ostensibly to look after ‘labour interests’. The SLFP High Command and Mrs. Bandaranaike had shown a great deal of reluctance because the SLFP did not want to be accused of appeasing the ‘Indian Tamils’…

Right from the start, Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government was dominated by Felix R. Dias Bandaranaike, an ambitious politician who had no scruples about pursuing diabolical policies to achieve his ends. Furthermore, within a short time the bureaucratic set up of Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government went completely into the hands of Sinhala Only cum Buddhist fanatics headed by civil servants like N.Q. Dias. What was worse was that more and more Sinhala extremists were brought into the administrative machine. Thereafter, only Sinhalese were recruited to the Army, and the Police, and unnecessarily heavy weightage was given to Sinhalese in all appointments in the public and even private sectors of employment.

Within a short time of the formation of the government, the SLFP leaders and government began to neglect and ignore the Federal Party. I reminded Badiuddin Mahmud who had become the Minister of Education of the promises made in March 1960 to the Federal Party about reintroduction of the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact. I also drew attention to the fact the government had already launched a vigorous campaign to implement the Sinhala Only policy with all its anti-Tamil implications.

Within a short time of the formation of the government, the SLFP leaders and government began to neglect and ignore the Federal Party. I reminded Badiuddin Mahmud who had become the Minister of Education of the promises made in March 1960 to the Federal Party about reintroduction of the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact. I also drew attention to the fact the government had already launched a vigorous campaign to implement the Sinhala Only policy with all its anti-Tamil implications.

It was only after a great deal of humming and hawing, in February 1961 – seven months after the government was formed that Baddiuddin took up the matter in the cabinet. At this meeting, Felix Bandaranaike, I learnt from several present, had made a joke of the whole thing and had said that the promise, if any, had been given in a completely different situation…and that ‘now’ the UNP should not be given an opportunity to incite the Sinhala people against the SLFP government. [dots, as in the original.] It was then that I realized that the even the liberal minded Bandaranaike husband, wife and nephew were only concerned about political power by securing the support of Sinhala extremists and that they were not concerned about the Tamils, be they Ceylon Tamils or Indian Tamils…

Mrs. Bandaranaike, in refusing to end the Sinhala-Tamil problem, threw away an opportunity undoing much of the damage done from 1956. The Federal Party, in spite of the fact that it was the SLFP which had introduced Sinhala Only, had been persuaded to help the SLFP to defeat the Dudley Senanayake Government in March 1960 on the promise the SLFP would revive the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam agreement which had been abrogated because of the racist campaign against it launched by the UNP – a campaign which had helped all jingoistic Sinhala chauvinists (including those in the SLFP) to cut the ground under S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s feet and compelled him to abandon his agreement with Chelvanayakam.

I was extremely disappointed that Mrs. Bandaranaike and other SLFP leaders did not seem to be in any way concerned with the fact that it was Mr. Chelvanayakam and the FP which had helped the SLFP to defeat the Mr. Dudley Senanayake government in March 1960 and that thereafter in the July 1960 elections the FP and the Tamil community helped the SLFP. If the FP had gone along with the UNP in March and July (when the UNP was prepared to have an electoral agreement with it) the story would have been different.

The FP was understandably angry that the SLFP should have broken the promises it had made in March 1960 and was even more annoyed that it had taken a tough line to suppress its February satyagraha. The FP thereupon extended its satyagraha into a civil disobedience movement…

From the time the SLFP went back on the promise it had given Mr. Chelvanayakam in March 1960, I began to get disillusioned with the Sirima Bandaranaike government. This was reflected in no uncertain way on two occasions in Parliament; first in my voting against the Government Amendment to the Immigrants and Emigrants Act which imposed harsh and brutal treatment on suspected illicit immigrants, contrary to civilized human rights rules; and the second, in voting for a Federal Party Amendment to the Throne Speech.

In thus, creating parliamentary history, I broke a convention that Nominated MPs in the Ceylon Parliament always voted with the Government, even though they may speak against some provisions of a Bill. Early in the history of the First Parliament (1947-1952), Mr. E.F.N. Gratien had abstained from voting on one Bill, and Mr. D.S. Senanayake had quickly kicked him upstairs to the Supreme Court Bench. Mr. Gratien no doubt preferred the freedom as a Judge to the constraints which inhibited a nominated MP.

I had good reasons for the way I voted, and I always set out the reasons in no uncertain terms…Accepting nomination as an MP, I had pointed out on every possible occasion, did not make me a ‘yes man’ of the government particularly on matters which affected Ceylon Indians…The ‘Independent’ line I took as a nominated MP vis a vis the SLFP did not lead to an immediate break with the government. Nor was there any attempt to sack me and deprive me of my ‘nomination’ as an MP. But in a number of ways I was made to understand that the government was in a position to ‘teach me a lesson’ in the hope, no doubt, that I will learn to ‘behave better’….

Although I was appointed the nominated member by the government to safeguard ‘Ceylon Indian’ interests, I soon realized that I was not even a proverbial ‘Voice in the Wilderness’. In fact, I found that I was not even consulted on matters that vitally affected the lives and the future of plantation Tamil community in this country…

When I met Nehru on October 4, 1963 in New Delhi, I brought to his notice that the SLFP government was planning to raise the question of the ‘stateless’ with the Indian Government with a view to concluding an agreement to secure repatriation of a large number of them in exchange for citizenship for a smaller number. Nehru told me that he and the Indian Government were totally opposed to any compulsory repatriation – whatever the bait offered to induce such repatriation. I made it clar to him as I had done so often in the past that ‘the Tamil plantation workers were born in Ceylon and they will work and die here’. I had also told him of the many difficulties they faced especially because of the government’s decision to stop employing stateless persons in the state and public sectors.

I had made it a point to mention to Pandit Nehru that there was a talk in SLFP government circles of a coming ‘deal’ with Indian about ‘sharing’ the stateless persons between the two countries. ‘No such nonsense with me’ he had angrily declared. ‘I will not agree to any horse deal’. But he died shortly afterwards and it was his successor Lal Bahadur Shastri who conducted the discussions and negotiations with Mrs. Bandaranaike at this meeting. I was not permitted to travel with a CWC delegation to be in New Delhi during the talks.

My visit to India when I met Nehru on October 4, 1963 was the subject of comment in parliament. At that time Ceylon was in the era of exit permits for travel. The government had the sole discretion to grant or refuse such exit permits. K.M.P. Rajaratne raised a question in parliament and said that I had gone to India under false pretences, that I had not disclosed that I was going to Delhi to meet Nehru and that I had obtained the permit to attend a Trade Union Conference.

The talks between Shastri and Mrs. Bandaranaike began in New Delhi on October 24, 1964. Before she went, she did not consult me or the CWC about the problem of the stateless. What was worse she refused permission for me and other CWC leaders to travel to India to present our case to the Indian Government. This was the setting for the Shastri-Sirima talks which led to the signing of an agreement which did not solve the stateless problem. But, it created a host of others…

I was angry about the agreement. I condemned it and called it a ‘horse deal’. I pointed out that neither the Indian nor the Ceylon Government had the right to negotiate and decide on the fate of the Ceylon Indians without consulting their representatives. I also accused Mrs. Bandaranaike of conducting negotiations behind my back. She had reacted with anger and on her return from New Delhi she had informed Parliament that the registered Ceylon Indians would be placed on a separate electoral Register. This was a scheme introduced by Sir John Kotalawela but condemned as retrograde by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and dropped…

I was always opposed to the Shastri-Sirima Agreement. I have at all times – even to this day – frankly declared that the Indian Government had made a mistake in ‘trading’ the rights of nearly half a million Ceylon Indians in this way. The majority of those repatriated were born in Ceylon – only their ancestors had come from India. The ‘sin’ for which they were repatriated was that they were of ‘recent Indian Origin’. The Indian Government through its High Commission Offices in Colombo and in Kandy had carried on a high-power campaign to persuade Ceylon Indians to opt for Indian citizenship on the promise of ‘rehabilitation’ adequate to enable them to start life anew in India.

This is how the Agreement was made ‘operational’. I shall at the appropriate time and place refer to the near total failure of the rehabilitation schemes of the Indian Government. Apart from this, 15 years after the signing of this Agreement over 80,000 of those who had registered themselves as Indian citizens were still in Ceylon – Sri Lanka by that time – and this in spite of two Acts to implement and hasten the repatriation…

...In December 2, 1964, [sic; the date was December 3] I had abstained from voting on the controversial Press Bill. My abstention had ensured the defeat of the government by one vote. If I had voted with the government it would have been a tie and the Speaker would have had to cast his vote in favour of the government and a defeat could have been averted….

For expressing opposition to the Press Bill I came under heavy attack from pro-Mrs. Bandaranaike SLFPers and LSSP stalwarts. Even the usually staid Mr. A.P.Jayasuriya had declared that I was ‘reactionary and an imperialist…’ [dots as in the original.] The LSSP, through its Lanka Estate Workers Union had mounted a campaign to discredit me. But, they failed to turn the plantation workers against me.

SLFP Period (1970-77)

The Marxist fanatics who took the SLFP-LSSP-CP Coalition on the slippery downward path of a regimented economic society have often claimed that it was the 1971 JVP revolt which made it necessary to hastily embark on Land Reform which proved to be self-defeating, counter-productive and economically disastrous. Land Reform to be valid should have been based on sound economic grounds. In the case of our 1972 Land Reform Law, it was one hundred percent motivated by sectarian political considerations. While the extent of land holding allowed for private ownership should have been determined on the fertility and other factors of usability, district-wise and area-wise Land Reform Law was based on an arithmetic norm of 50 acres per adult private owner whatever the nature of land, its location or its conditions. All the rest to the privately owned land was vested in the State….It is now a matter of record that the Land Reform Law was utilized to wreak revenge on political opponents and the very small segment of land owning Indian Tamil community to even deprive them of their shelter. The entitlement of individuals of land even within the ceiling of fifty acres was swept aside as fancy directed the Ministry concerned. The Land Reform Law was made an instrument to terrorise and uproot individuals from their home and hearth. The vindictive application of this law can be assessed by the fact that where the Land Reform was not applicable, the Land Acquisition Act was invoked for this purpose.

Apart from this gross injustice perpetrated on certain people, a greater vicissitude was visited on organized labour in the denial of trade union and other rights to workers on estates taken over by the Land Reforms Commission. The government, which in its first Throne Speech on 17th June 1970 pledged: “A comprehensive charter of Worker’s Right will be introduced: this will include the revision of Labour Laws, provision for security of employment, the acceptance of the principle of equal pay for equal work, the abolition of discrimination due to the medium or instruction; compulsory recognition of trade unions by employers, bonus payments, increase of EPF contributions; welfare services etc. Legal provision will be made to see that casual and temporary workers both in the public and private sectors can become permanent after a definite period of service and that employees in the private sector cannot be dismissed without an independent prior inquiry.”

The Ministry of Labour appointed a Committee of Inquiry in July 1970 to draw up a Charter of Worker’s Rights among other matters. Events have proved that the actions of the Minister of Lands were diametrically the opposite to the promise held out in this pledge. It is an indictment on the government and the makers of its policy that the Land Ministry has proceeded to create conditions inhibiting the development of trade unions and the proper functioning of the process of individual freedom. The union dues, check-off system for the first time applied to private industry on account of the initiative taken by the CWC extended by law by the UF government to all Unions, has been arbitrarily frozen on estates taken over by the Land Reform Commission.

The unplanned and ill-conceived haste in which estates were taken over, dislodging members of the estate staff in the process within a matter of hours, caused immense hardship to the workers by way of obtaining documents for citizenship inquiries and for purpose of gratuity in the event of repatriation and retirement. These factors and difficulties visited on the workers produced a consensus of protest from all trade unions, pro-Government and otherwise towards the end of 1972, resulting in a series of conferences with the Commissioner of labour and memoranda to the prime minister which however have failed to create an impact on the Minister of Agriculture and Lands, Mr. Hector Kobbekaduwa.

It must be recorded with sense of achievement that the action taken by the CWC prevented a mass scale displacement of labour from these estates. Apart from practices well established in the industry, even the legal minimum concerning wages and other benefits of the workers were thrown overboard on estates in the LRC to the extent of paying workers governed by the minimum wages law, wages by result, i.e. payment of wages on poundage basis. However, prompt action by the unthrough the Commissioner of Labour put a stop to this practice and its spread to other estates in the LRC.

The CWC had brought to the notice of the government that threats, intimidation and assault had all become a part of the daily routine of the workers on these estates. Workers had been forced out of employment to no bigger crime than trade union activities. We had pointed out that the management on some of these estates had adopted the following measures to terrorise the workers into submission: (a) Refusal to negotiate with unions to settle disputes; (b) Denial of trade union rights; (c) Deprivation of existing practices; (d) Denial of assistance to applicants for Indian and Sri Lanka citizenship; (e) Non-payment of earned wages; (f) Non-recovery of dhoby and barber allowances; (g) Denial of rations and other subsidiary foodstuffs; (h) Non-issue of free milk to infants and tea to pensioners; (i) Non-payment of full maternity benefits; (j) Shutting down of educational facilities; (k) Denial of minimum wages; (l) Denial of monthly cash advances; (m) Lack of credit facilities; (n) Non-payment of statutory dues to repatriates.

One of the really difficult and sensitive problems of this period centered around the implementation of the Sirima-Sastri Agreement of 1964. In the last chapter, I examined the implications of the agreement about which neither I nor the CWC had been consulted. Statutory provisions were made by the Dudley Senanayake government, soon after it came to power in 1965, to ensure a fair and reasonable implementation of the agreement. Unfortunately bureaucrats with their pro-Sinhala Only inhibition had made any real or satisfactory implementation impossible. I also drew attention to the fact that SLFP had been highly critical of what it termed ‘concessions’ to the Indian Tamils by Dudley Senanayake in his Implementation Act. The SLFP was particularly opposed to the decision to allow Indian Labour to remain on the estates pending the implementation of the agreement…

The Governor General in his Speech from the Throne had declared that the Indo-Ceylonese Pact of 1964 would be speedily implemented. This was necessary because almost five years after the Pact was signed and ratified, only 12,799 persons of Indian origin had been repatriated. Sri Lanka had already fulfilled its quota of granting citizenship to 7,316 persons upto 30 June, 1970. In addition, 1,220 children born after the date of the agreement had also been granted Sri Lanka citizenship.

At this stage, as a goodwill gesture, the Indian High Commissioner in Colombo put forward a plan popularly known as the ‘Puri Plan’. Under the plan, India agreed to take back 50,000 persons annually who had bonafide claims for Indian citizenship prior to the conferment of Indian nationalisty. The provident fund claims of potential Indian citizens were to be decided on the recommendation of the Indian High Commissioner. Though the Government of Sri Lanka discussed the plan on 15 November, 1970, the plan apparently failed to receive a favorable response. Consequently, the novel idea died prematurely because of governmental apathy and a skeptical public opinion in Sri Lanka. Notwithstanding the abortive Puri Plan, and Dudley Senanayake’s alleged lethargic approach to the problem of the ‘stateless’, Mrs. Bandaranaike took the initiative to hasten the implementation of the Pact. To expedite the process of repatriation of the persons of Indian origin to India, Mrs. Bandaranaike brought in an amendment to the Indo-Ceylon agreement (Implementation) Act of 1967, which was adopted. Mrs. Bandaranaike declared in the House that she ‘had to bring this amendment in order to keep strictly to the terms of the Pact. The amendment to Section 8 was to incorporate the provisions of the Indo-Ceylon Agreement of 30 October 1964 that the number to be granted Ceylon citizenship will be in proportion to the number repatriated to India’. Further, Mrs. Bandaranaike regretted the delay in the implementation of the Pact during the last seven years. ‘We could have repatriated’ she maintained, ‘about 150,000 persons to India, but we had not sent back even the one-fourth of this number. We are dedicated to implement the Pact in letter and spirit and we will repatriate them as quickly as possible.’

The Government of India which had kept silent during the passage of the 1967 Implementation Act faced some angry exchanges from the Opposition Members in the Lok Sabha on 23 June 1971. Replying to the debate, Surendra Pal Singh, Minister of State for External Affairs, said that ‘the present amendment is to the Ceylonese domestic legislation of 1967 and not to the 1964 Indo-Ceylone Agreement,’ and ‘…it only brings their own enactment in line with the 1964 agreement. It does not come into conflict with the 1964 agreement.’ [dots, as in the original.] This was, in effect, a public acclaim of an understanding which Mrs. Indira Gandhi and Mrs. Bandaranaike had apparently arrived at when they met during the Non-Aligned Conference at Lusaka in September 1970. It would be seen that the Government of India had endorsed the couse of action Mrs. Bandaranaike intended to take.

Meanwhile, the progress made in the implementation of the agreement in nearly three and a half years was not satisfactory, as is evident from the table below:

| Year | No. of Persons repatriated to India |

| 1970 | 8,733 |

| 1971 | 21,867 |

| 1972 | 27,575 |

| 1973 | 33,172 |

| 1974 | 35,141 (plus 9,837 as natural increase) |

This implied that not withstanding her efforts Mrs. Bandaranaike had not succeeded in fulfilling the stipulated number of 35,000 person to be repatriated every year. Also, by 1972 it was realized by her that the number of person desirous of acquiring Ceylonese citizenship was far in excess of the number stipulated in the past. As such, she appealed to the Indian Prime Minister to reopen the register in the Indian High Commissioner which was closed in April 1970, so that the persons of Indian origin whose application for Sri Lanka citizenship were rejected might apply for Indian nationality. Consequently, a ten-member delegation of Indian officials headed by the Foreign Secretary, Kewal Singh, arrived in Colombo on 13 February [1971], for a four day visit. It was reported that the talks had been deadlocked on two issue: (1) the Ceylonese proposal that India reopen its list, and (2) the increased rate of annual repatriation. These issues appeared to have been the basis of Mrs. Gandhi’s discussion with her counterpart in Sri Lanka, when she visited the island from 27 to 29 April 1973.

In the talks during her visit, Mrs. Bandaranaike expressed a hope that India would absorb, over the next eight to nine years, a progressively increasing number of Sri Lanka residents of Indian origin who had opted for Indian citizenship. She made it clear that Sri Lanka expected that figure for this period. The duration of the agreement was also to be extended up to 1982 (originally 1979).

However, the Indian government was not inclined to accept the Ceylonese request for reopening the register for the registration of the repatriates. India believed that those numbering about 400,000 would had applied for Indian citizenship should be disposed of before inviting new applications. India had also pointed that if Ceylon rejected more applications, involving another 325,000 persons, the number of rejected applicants would far exceed the 525,000 persons which India had agreed to take back. Further, India was unwilling to reopen the register presumably on the grounds that there was no guarantee that the residue of 150,000, not covered by the Agreement, would not apply for Indian citizenship. And it was feared that fresh applications might not be entirely on voluntary basis. However, it is interesting and surprising to note that Mrs. Bandaranaike did not raise the issue of the problem of the residue number, left over in the 1964 Pact, during Mrs. Gandhi’s visit. Further discussions were put off and the solution was evolved during the return visit of Mrs. Bandaranaike to New Delhi.

Mrs. Bandaranaike went to India on 22 January 1974 for a week-long tour to solve a ‘few issues’. It was during this visit that the issue of the residue, which had not been covered by the Indo-Ceylonese Pact of 1964, was taken up. India and Sri Lanka pledged to share the remaining 150,000 persons of Indian origin. Under the January 1974 Agreement, India agreed to take back 75,000 persons. Sri Lanka, on the other hand, assured India that until their repatriation, they would be allowed to enjoy all existing facilities in Sri Lanka. The process of repatriation of these persons was to begin only after 525,000 person of Indian origin covered by the 1964 agreement had crossed over to India.

Though the Sirimavo-Shastri Pact is a landmark in the realm of Indo-Sri Lanka relations, its implementation was beset with many hurdles. This is evident from the fact that, till 1970, very little headway was made regarding the grant of citizenship by both the countries, especially Sri Lanka.

Up to the end of 1974, 274,455 persons had been recognized by the Indian High Commission as citizens of India. Of this number, 106,423 had been repatriated till January 1974. On the Ceylonese side, 60,813 persons were granted Sri Lanka citizenship till the end of 1973. The progress of repatriation was on an average of 11,202 persons with the maximum number of repatriates being 35,141 in 1974 and the minimum being 512 in 1965. If the speed of repatriation remained the same, it used to take, Sri Lanka nearly 38 years to repatriate the remaining persons of Indian origin to India.

As far as India was concerned, the annual report of the Rehabilitation Department disclosed has many as 10,643 families had arrived during 1974 and 14,168 families had been given rehabilitation assistance by way of employment on the plantation areas, grant of business loans and allotment of cultivable land till the end of 1974. However, taking into consideration the admission in the report that employment on the plantation has almost reached a saturation point, the economic prospect of the future immigrant (90 percent of whom have been from the plantation areas) appears bleak.

No doubt, the repatriates on arrival in India got loans to finance business, for construction of houses and the like. Under the land commission scheme, upto Rs. 4,650 per family was given, provided the value of assets brought by them did not exceed the limit. Repatriates who opted for cultivation of their land were given financial assistance ranging from Rs. 3,105 to Rs. 4,359 which was determined on the size of the land holding. But this was a meager sum not enough to start life in a ‘new’ country. A large number of them had been reduced to destitution. The problem of statelessness was not solved by the Srima-Shastri Pact. It was resolved only through legislation in 1986 and 1988.

Though the Indo-Ceylon Agreement had been reviewed on a number of occasions, the agreement in January 1974 was said to have finally resolved the question of the statelessness of the people of India origin in this country. The Ceylon Workers’ Congress however, had consistently opposed the phasing of the granting of citizenship and repatriation over a period of 15 year envisaged in the original agreement of 1964 on the ground that such phasing will perpetuate the state of statelessness of the affected persons. During the course of the discussion I had with Mrs. Gandhi in the course of her visit on the 27th of April 1973 I had stressed that any solution of the ‘stateless’ problem was a matter that had to be given careful consideration as it affected the development of persons as human beings and that this could be achieved only through the generation of goodwill. The Indian Prime Minister agreed to give consideration to the representations made by me and the CWC….

In terms of the Indo-Ceylon Agreement a total of 191,571 persons had left for India by 1974. The CWC had continued to assist these repatriates in various ways such as purchasing their railway tickets, luggaging their effects and also providing them shelter in our office premises for overnight stay whenever the need arose. The CWC made representations to both the representatives of the Government of India and to the Government of Sri Lanka of the manifold difficulties that repatriates had to undergo before and after their repatriation….

In October 1973 the government started the first of its recourses to gazette notifications to impose a drastic cut in the food items issued to consumers both in and outside the estates. While the rice on ration was cut by half to bring it to one measure from two measures, the free issue was restricted to half a measure and the quantity of flour to one pound per person for a week. This quantity was further reduced to one pound of atta flour for an estate worker for a week. In the meantime, government clamped down Emergency Regulations banning the transport of rice and paddy. The ban of the movement of rice however was modified after a vehement protest by the joint Opposition.

A direct consequence of the food situation was the unprecedented rise in the death rate on the plantations. This was commented on by even the medical officer in charge of the Planters’ Association Health Scheme, Dr. L.V.R. Fernando who stated that the increase in the death rate on the plantations was solely due to insufficient food available to the estate population. International focus was so widespread on the near starvation condition suffered by the estate workers that two little girls from Scotland Anjela and Fiona de Saram sent their pocket money to help the plantation workers. This gesture of these two little girls are one that humanity should be proud of. The question we were constantly posing to the government was whether a worker could live on a half measure of rice and a pound of flour for a week. The CWC appealed to International Organisations like the FAO and the International Red Cross Society for dry rations to estate workers but were baulked in its attempts in this direction due to the fact that these organizations would respond only to governmental requests.

In this background it defies every concept of right thinking that the government should have resorted to Emergency Regulations to evict the workers who had gone to the Eastern Province to open up cultivation plots in May 1973. I brought it to the notice of the government that extra legal methods were being adopted to get rid of these cultivators who had proceeded to the Eastern Province to cultivate food when the country in general and the plantation workers in particular were in the grip of man-made famine conditions.

I had also brought to the notice of the Prime Minister in July 1974 that the famine conditions prevailing on the estates compelled workers to go to provincial towns to procure food or to earn a pittance to augment their family income. I complained that such people were being bundled into lorries and marooned in distant places whenever a Minister or a politico happened to visit these towns. We conveyed to the Prime Minister the fact that some of the persons responsible for this type of atrocious action were in some cases the police and in other cases officials of local bodies. We appealed to the Prime Minister to end this type of inhuman activity….

The popularity of the government had begun to vanish. In all the by-elections in this period – in Nuwara Eliya, Ratnapura, Kesbewa, Puttalam, Mannar, Kankesanthurai, Colombo Central, Colombo South and Dedigama, the government faced badly. It lost all the by-elections, except two and in the one at Ratnapura the majority of the SLFP was halved. The Kankesanthurai by-election was held after three years from the date the leader of TULF resigned his seat as a challenge to the government against the promulgation of the 1972 Constitution. The TULF leader won by an overwhelming majority, so also did J.R. Jayewardene who had resigned his seat as a mark of protest against the government’s extending its term of office from five to seven years. He doubled his majority. In the period 1970-77, there were 13 by-elections. The UNP won 10, the TULF won 1, and the SLFP won two and both on reduced majorities…

By the middle of 1975, the popularity of Mrs. Bandaranaike and her UF Government had all but vanished. Neither the Land Reform Law nor the Republican Constitution appeared to have made an impact on the people…

There was no doubt that the ‘socialist’ policies and programmes of the LSSP, the CP and their fellow-travellers in the SLFP wanted more and more authoritarian ‘socialist’ measures to save the situation, but Mrs. Bandaranaike and the majority of the SLFP did not want away more ‘extremist’ economic measures. A major dispute arose between Mrs. Bandaranaike and the LSSP in mid 1975 and on September 2, she expelled them…

I contested the Nuwara Eliya seat [in the 1977 General Election]. It had been made a three-member seat. I entered the fray because a sufficiently large number of Tamils of Indian origin who had become citizens were on the voters list. The voting strength which was 24,024 in 1970 was 64,407 in 1977. The SLFP had increased the voting strength of the Sinhalese by large scale state-aided colonization schemes in the area. It fielded Anura Bandaranaike as its candidate. On the strength of Tamil voters, I should have been the First Member, but when the votes were counted, I was third. The voting was as follows: Gamini Dissanayake (UNP) 65,903; Anura Bandaranaike (SLFP) 48,776; and Thondaman had 35,743 votes.

I had been deprived of a large number of votes which should normally have been cast for me through a trick – with the aid of a false letter addressed to the Tamil voters of Nuwara Eliya purporting to be issued by a Gandhian organization in India calling upon Indian voters to give at least one (or more) of their three votes to Gamini Dissanayake (hinting that Thondaman had enough votes to win with ease). This gimmick or trick was only one of the many used against me. It was surprising that this trick should have been used against me by supporters of the UNP. The CWC had cooperated with the UNP from 1965 especially in the difficult years from 1970 to 1977. The CWC had helped the UNP in all elections from 1965. It had also helped to persuade the Ceylon Tamils of the FP, TC and TULF to vote with the UNP in these elections. I had excellent relations not only with UNP leader J.R. Jayewardene but also with nearly all the leading members of the UNP. I was greatly saddened by this trick played on me but I took it in my stride as part of the price one has to pay for playing the ‘democratic’ game.

It was most unfortunate that post-election violence assumed serious proportions after the July 1977 elections. Whilst UNP supporters attacked selected SLFPers, disappointed SLFPers had turned their wrath on the Tamils for having supported the UNP – but this was done under cover of fighting separatists (Eelam). Whilst in the 50’s and 60’s, such Sinhala violence was directed against the Ceylon Tamils, in the 1970, such violence was let loose against the plantation Tamil workers under cover of implementing Land Reform and also for helping the UNP at the elections. The attacks on Tamil plantation workers continued into the 1980s and it stopped only after the CWC took adequate counter measures against such attacks.

Coda

Thondaman’s story stopped at the end of 1977. He concluded volume 2 as follows: “The next stage of my story, which will set out in the next chapter – the First in Volume Three of my Autobiography. It will take my story forward from 1978 to the present day.” As Thondaman died in 1999, we don’t know, whether volume 3 currently exists in any format (as a written script or recorded oral tape).

It is most depressing that Arumugam Thondaman (the current leader of CWC and the grandson of Saumiamoorthy Thondaman) is a pale shadow of his grandfather. He simply lacks the courage, gravitas and temperament to dictate terms to Sinhalese political leaders.

Cited Sources

Anomymous: Towards midnight. Economist, July 22, 1989, p. 31.

Anonymous: War of Guns and Words. Asiaweek (Hongkong), July 28, 1989, pp.18-20.

Delhi Correspondent: Gunning for Gandhi. Economist, July 29, 1989, pp.31-32.

Desmond E: Facing Up to The Tough Guy. Time, July 24, 1989, pp.22-23.

Sabaratnam T: Out of Bondage – A Biography. The Sri Lanka Indian Community Council, Colombo, 1990, chapter 13 – A War Averted. pp. 229-250.

S. Thondaman: Tea and Politics An Autobiography, vol.2: My Life and Times. Navrang (New Delhi) and Vijitha Yapa Bookshop (Colombo) Co-Publishers, 1994. Selected excerpts from Chapter 5 ‘Srimavo’s SLFP 1960-64, Disillusioned’(pp. 175-201) and Chapter 7: SLFP at the Helm 1970-1977 A Difficult Period (pp. 239-295).

© 1996-2025 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.