Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Apocalypse in Our Timeby Ravikumar, Run From Big Media, mostly Delhi, December 8, 2010

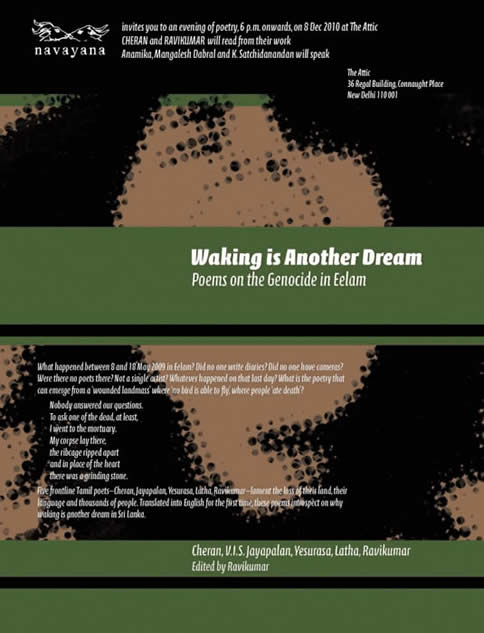

Waking is Another Dream: Poems on the Genocide in Eelam, a slim anthology edited by Ravikumar, will be launched by Navayana on Wednesday, 8 December 2010 at 6 p.m. at The Attic, 36 Regal Building, Connaught Place, New Delhi. [Can be ordered from http://navayana.org/?page_id=3] At a time when the Eelam issue is the news again owing to Channel 4’s coverage leading to the cancellation of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s talk at Oxford, citing emerging evidence of his war crimes, Navayana presents a volume of powerful poetry translated for the first time from Tamil into English. Says poet Cheran, “The lack awareness in a city like Delhi on the fallout of the genocidal war in Sri Lanka is appalling. People here who seem concerned about Palestine or even Kashmir seem utterly indifferent to the problem in India’s own backyard.” A modest effort to combat such indifference and ignorance is Waking is Another Dream. The book features the work of five leading Tamil poets—Cheran, Jayapalan, Yesurasa, Latha, Ravikumar—on the Eelam issue.

Cheran is a major Tamil poet and playwright who has published seven anthologies of poetry in Tamil. His poems have been translated into English, German, Swedish, Sinhala, Kannada and Malayalam. He is a professor at the University of Windsor, Canada. Other speakers at the event are litterateur K. Satchidanandan (former editor of Sahitya Akademi’s Indian Literature) and eminent Hindi writers Mangalesh Dabral and Anamika. On the eve of the book's launch, Kafila offers its readers an exclusive excerpt from the anthology Introduction, "Apocalypse in Our Times".] Martin Luther King said that war was a poor chisel to carve tomorrow. Wars taking place around the world prove that military aggression can indeed destroy the future. It is said that ‘truth’ is the first victim of a war. And yet, the last corpse that is removed from the battlefield is the corpse of truth. Perhaps because that corpse cannot be easily buried, no one comes forward to claim it. The corpse of truth lies in wait like a landmine. When it explodes, the citadels of falsehood built over it fall apart. While the world seems to have almost forgotten the genocide that took place in Eelam, the Jaffna-based University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR) has published a comprehensive 158-page report, “Let them Speak: The Truth About Sri Lanka’s Victims of War”, that details the events that took place from the latter half of 2008 to 18 May 2009, when it was officially announced that the war on Eelam Tamils had come to an end. Using eyewitness accounts from people who had lived in the war zone, this report also records the happenings in the crucial period from 8 to 18 May 2009. Whereas news reports in the mainstream media in Tamil Nadu and elsewhere, about the genocide of Eelam Tamils, were based on speculation and fabrication, the UTHR report documents the atrocities in detail. UTHR is equally critical of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan government. The Sri Lankan government’s brutal massacre of the Tamils and continued distortion of the truth in communications with India and other nations are exposed in this report. Among other things, the report exposes the tactics employed by the Sri Lankan government to give false figures of the number of people in the war zone, and points to how, even today, the government plays with numbers when accounting for the people in refugee camps. Some human rights organizations claim that about 3,000 Tamils were killed between January 2009 and the first week of March. Contesting these figures, the Tamil Rehabilitation Organization, which worked among those displaced or affected by the war, claimed that at least sixty to ninety people were killed each day; on that basis, they informed media organizations that the number of casualties in this period could add up to 6,500. The estimates provided by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are even higher. A female doctor who was working with the health department of the LTTE has said that a total of 37,000 people were killed in this time span. Several ‘embedded intellectuals’ in India issued statements to the effect that people in the barbed-wire camps have been sent back to their own homes. The UTHR report gives some insight into the suffering that makes Tamil detainees eager to return home. As the Sri Lankan government makes clear, detainees in the camps are released only after ‘thorough investigation’. In the name of investigation, extreme human rights violations have been, and are being, orchestrated. The Sinhalese army tortures detainees at will, since any detainee may be accused of being an ex-LTTE cadre. Young women with cropped hair, for instance, are subjected to questioning on the grounds that they appear, visually, to be members of the rebel forces. The UTHR report also brings to light the corrupt practices of the Sinhalese army, which takes bribes from the people living in these camps. But for a few news reports that appear sporadically, there is no real information about the sexual exploitation of Tamil women in these camps. The Sinhalese soldiers come to the camps at night, take young Tamil women away in vans and drop them back early in the morning. Women who have been taken away in this manner find it difficult to come to terms with the trauma that they have faced, and lack the courage to disclose it to others. Not only in the camps, but even in the hospitals, there is no dearth of atrocities committed by Sinhalese army personnel. In a testimony recorded in this report, a doctor who worked at the Vavuniya hospital speaks of how the Sinhalese army randomly took away young men being treated at the hospital. He says not a single person who was carried off in this fashion returned to the camps. The UTHR report points out how the absence of proper records of people undergoing treatment at hospitals has made it impossible to trace details of where an individual was brought from, and where s/he has been taken to by the army. The report also records how the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime in Sri Lanka has misled the Indian government. When international NGOs tried to complain about the camps, not only did the Sri Lankan government threaten that their visas would be cancelled, but it also warned them that legal cases would be filed against them. As a result, many witnesses remained silent. In late 2006, the government of Sri Lanka signed an agreement to set up a thermal power plant with help from India’s National Thermal Power Corporation Limited. It selected Sampur as a site for that proposed plant. In order to clear out the people who were living there, the government of Sri Lanka conducted aerial bombings. Hundreds of people were killed in the shelling and the rest of them abandoned their homes and fled to safer areas. The government banned their return to Sampur, declaring it a High Security Zone. These actions took place with the knowledge of the Indian government. In March 2009, the Indian government opened a hospital in the war zone. Several hundred people received treatment there. The doctors who worked there had inside knowledge of the Sri Lankan government’s anti-Tamil attitude. On one occasion, Basil Rajapaksa, the president’s brother and advisor, brought a few journalists to the hospital. An Indian doctor confronted Basil Rajapaksa with a fragment of a bullet, and said: “I surgically removed this from near the heart of a six-year-old child. You say that you are only targeting terrorists. Is a six-year-old child a terrorist?” Basil Rajapaksa is said to have walked away without giving a reply. By keeping people treated at the Indian hospital hidden from the outside world, the Sri Lankan government was able to show reduced figures of wartime casualties. Even now, India continues to help Sri Lanka with removing landmines. Fearing that the mass graves of thousands of people would come to light, the Sri Lankan government has refused the help of several countries and is taking only India’s help in clearing the landmines. Eelam Tamils look at this as an act of betrayal by the Indian government. The widespread view among the Tamil people is that if the graves of the massacred Tamils are exposed to the world, Sri Lanka will be investigated by the International Court of Justice; and that in order to shield Sri Lanka, India is now involved in demining. When the Indian parliamentary elections took place in May 2009, media reports suggested that in response to requests from the Indian government, the intensity of attacks on Eelam had been reduced. On the contrary, having gathered all the facts about the war, the UTHR investigators state that the Sri Lankan government did not show any special consideration to India. The report blames Sri Lankan power-holders for trying to bring the war to a close before the end of the Indian general elections. The present political situation in Sri Lanka is dangerous for democracy. The report argues that the onus of creating a democratic political climate lies not only with the Tamils but also with the Sinhalese. The poisonous situation can be altered only when democratic forces consisting of both Tamils and Sinhalese work together. Eyewitness accounts of the war have been given in the UTHR report. When writers have fallen silent, only these testimonies portray the blood-drenched story of the genocide that took place in Eelam. Today, when death is the prize for speaking the truth, silence has become the language of the Tamils. They are unable to say anything, even to those who go in search of them, seeking the truth, because the Sinhalese army has ears everywhere. Overcoming this constant fear of death, a few Tamils have come forward to share their stories with UTHR. Here is one such testimony:

It is well-known that the genocide of the Tamils in Eelam involved the violation of international war conventions and protocols. We are also aware of the talks that the Tigers conducted with the government of Sri Lanka, including their decision to give up arms. They were asked to carry white flags, but those who went ahead unarmed and bearing the flag of peace were shot dead mercilessly. Nowhere else in the world have we witnessed people taking shelter in bunkers being buried alive with bulldozers. Not one or two persons, several thousand people have been murdered in this manner. Even after the announcement on 17 May that the war was over, massacres continued to take place in Mullivaikkal. Those who had managed to escape were hunted down and ruthlessly killed by the government of Sri Lanka. How do Tamils there deal with this scenario? Having suffered unimaginable violence, do they express their sorrow in writing? The ethnic riots of 1983 introduced us to extremely talented poets from Eelam and their poetry collections changed the course of political poetry in Tamil Nadu. M.A. Nuhman’s Mazhainaatkal Varum (The Rainy Days Shall Come), Sivasekhar’s Nadhikarai Moongil (Bamboo by the River Bank), A. Yesurasa’s Ariyapadathavargal Ninaivaga (In Memory of the Missing), Cheran’s Rendavadhu Suriyodhayam (The Second Sunrise), V.I.S. Jayapalan’s Suriyanodu Pesudhal (Speaking with the Sun), Vilvarathnam’s Akangalum Mugangalum (Hearts and Faces), the Eelam women poets’ Solladha Sedhigal (Untold Stories), Nuhman and Cheran’s anthology Maranthul Vaazhvom (We Will Live in Death) that featured eleven Eelam poets: these volumes were among the unforgettable outpourings of that time. There were magazines like Alai (Wave) and later, Serinigar. The support for the Eelam cause in Tamil Nadu grew out of such books. Intellectuals here, in India, like Thamizhavan, S.V. Rajadurai, Bothiyaverpan, Crea Ramakrishnan and many others helped with the publication of these books. On the one hand, the supporters of the Tigers held tear-filled exhibitions, and on the other hand, these books created a silent revolution. Apart from this, members of the Marxist-Leninist movement had intense debates on the ethnic struggle. The Tamil problem was investigated along with the struggles of other oppressed nationalities in India. Not only Tamil writers, but even Sinhalese intellectuals like Kumari Jayawardene contributed to this discourse. Today, I look back with nostalgia at all that ferment of thought and feeling. The support for Eelam in Tamil Nadu was not only emotional but also intellectual. The reasons for its current absence need to be investigated. As I write this, it is nearly a year since the Mullivaikkal tragedy. How is the Tamil intellectual circle going to pay homage to the victims? When I was thinking of this in September 2009, I chanced upon an early poem of Cheran. I was amazed at the far-sightedness of poets. I shared that poem with friends over email. Apocalypse The apocalypse happened in our own time. Earth shaking in smokescreens Body splitting in satanic rain Fire raging within and without Night’s howling flood Dragging children, people Burning them in an inferno In those days, we ate death Throwing a lifeless sidelong glance At the helplessness of spectators Fuming, fuming, like a cloud We began to rise up Kafka did not get the chance to feed his writings to fire But Sivaramani burnt hers A poem is destroyed in an uneasy space And the compositions of others Refuse to come alive All of us have gone away There is no one to tell stories Now there is A wounded landmass No bird is able to fly over it Until we return A few lines of this poem moved me deeply. Sivaramani committed suicide on 19 May 1991. She was a powerful voice that emerged from among the Eelam women poets of her time. Before she died, she burnt all the copies that she had of her poems She wrote: “My days/ You cannot snatch away./ Like a small star/ that descends/ between your fingers/ that cover your eyes/ my existence is certain.” Sivaramani showed her opposition to the denial of freedom by taking her own life. But the fighters did not have the patience to learn any lessons from this. Therefore, those who tried to express their opinion there ‘ate death in those days’, ‘when the spectators were helpless’, ‘when the poem was destroyed, the compositions of others refused to come alive.’ There is a long list of those who have been silenced in Eelam. Where there are people with sensitivity, there freedom gains further respect. When all of them have been silenced, we can deduce who will rule. How can poetry come from such a space? I realize that Cheran’s poem contains the answer to why there no longer are intense poetic voices from Eelam. ‘All of us have gone away/ There is no one to tell stories’ so that, ‘Now there remains/ A wounded landmass/ No bird is able to fly over it/ Until we return.’ Here, ‘we’ is not a limited reference to expatriate poets like Cheran. It is a pronoun that denotes every creative voice that does not submit to power, but aspires to freedom. This small anthology is just an effort to create faith in such voices. ----------------------------------------------------------------- A Feast of PoetryNavayana is proud to present four new, cutting-edge poetry collections. These will be launched on 8 Dec 2010 at 6 p.m. at The Attic in New Delhi. Canada-based Eelam poet Cheran and Ravikumar from Chennai will be present at the launch of Waking is Another Dream. Ramesh Gopalakrishnan, South Asia Researcher with Amnesty International, will join them. Poets Anamika, Mangalesh Dabral and K. Satchidanandan shall speak on the occasion. In these “Poems on the Genocide in Eelam”, edited by Ravikumar, five frontline Tamil poets—Cheran, Jayapalan, Yesurasa, Latha, Ravikumar—lament the loss of their land, their language and thousands of people. This powerful work demands that we not look away from the genocide in own backyard, where war crimes compare with Abu Gharib, as this Channel 4 news clip, that led to the cancellation of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s talk at Oxford earlier this week, demonstrates. On the eve of the launch, poet Cheran said, “The lack of awareness in a city like Delhi on the fallout of the genocidal war in Sri Lanka is appalling. People here who seem concerned about Palestine or even Kashmir seem utterly indifferent to the problem in India’s own backyard.” Cheran is a major Tamil poet and playwright who has published seven anthologies of poetry in Tamil. His poems have been translated into English, German, Swedish, Sinhala, Kannada and Malayalam. He is a professor at the University of Windsor, Canada. Ravikumar’s Introduction to this volume, Apocalypse in Our Time, has been excerpted in Kafila. Among the other poetry offerings from Navayana is “a feast of flesh”. N.D. Rajkumar, born into a traditional shaman community in a border town between Kerala and Tamil Nadu, cracks open a world that offers the modern reader stunning glimpses into a magic-drenched, living dalit history. His Tamil poems have been rendered in English by Anushiya Ramaswamy in the collection Give Us This Day A Feast of Flesh. In Ms Militancy Meena Kandasamy stands myths on their heads in highly experimental poems, which critic and poet K. Satchidanandan says, “shock and sting the readers until they are provoked into rethinking the ‘time-honoured’ traditions and entrenched hierarchies at work in contemporary society”. Finally, there’s a re-issue of Namdeo Dhasal’s high-voltage, bruising poetry. First published in 2007 as a hardback edition, the paperback is titled A Current of Blood. All these printed on earthy brown craft paper and priced invitingly between Rs 150 and Rs 180. To buy all four titles at a discounted rate of Rs 600 (inclusive of postage, within India), send a DD in favour of “Navayana Publishing” and mail it here. All titles can be ordered online, across the world, from Scholars Without Borders. |

||

|

|||

D. Ravikumar, the editor of the volume, happens to be an MLA with Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (Dalit Panther), which is part of the DMK-UPA alliance in Tamil Nadu. Along with Toronto-based poet Cheran, Ravikumar will be present at the launch.

D. Ravikumar, the editor of the volume, happens to be an MLA with Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (Dalit Panther), which is part of the DMK-UPA alliance in Tamil Nadu. Along with Toronto-based poet Cheran, Ravikumar will be present at the launch.