Ilankai Tamil Sangam29th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

In Sudan, a Colonial Curse Comes Up for a Voteby Jeffrey Gettleman, The New York Times, January 8, 2011

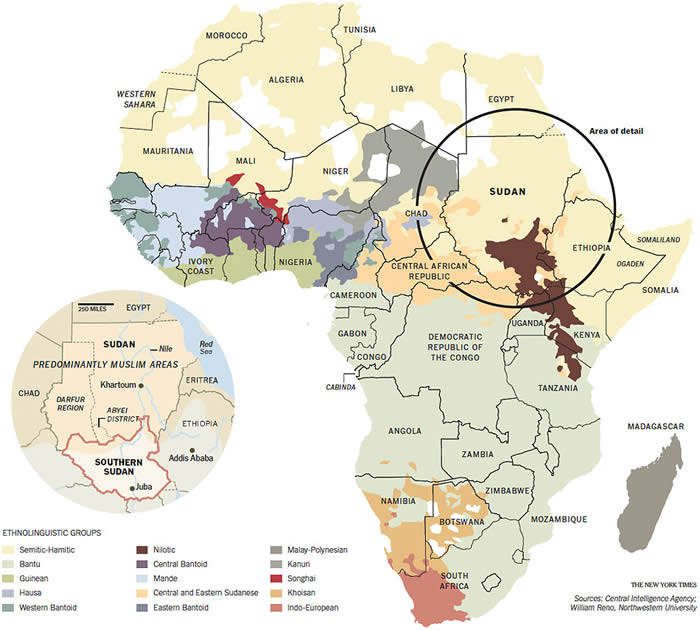

A Continent Carved Up, Ignoring Who Lives Where The map of today’s African nations looks much like the map drawn by Europeans to meet their own interests: diverse groups are scattered across many countries with little concern for ethnic links. The patterns shown here represent only the broadest ethnic and language groupings; within those are further divisions, like tribe and clan, too numerous to show. Areas in white are sparsely populated or lack data.

More than any other continent, Africa is wracked by separatists. There are rebels on the Atlantic and on the Red Sea. There are clearly defined liberation movements and rudderless, murderous groups known principally for their cruelty or greed. But these rebels share at least one thing: they direct their fire against weak states struggling to hold together disparate populations within boundaries drawn by 19th-century white colonialists. That history is a prime reason that Africa remains, to a striking degree, a continent of failed or failing states. And it helps explain why the world is now trying to stand behind southern Sudan as it votes, starting Sunday, on cutting its ties to the Sudanese government in Khartoum. Voters are expected to approve independence, and if it does, South Sudan will become a rare exception in Africa — a state that is reorganizing its colonial-era borders. It might even set a precedent for others. In any case, it has already set off an agonizing debate, a half-century in coming, over the wisdom of trying to hold together the unwieldy colonial borders in the first place. Even though many of those frontiers carelessly sliced through rivers, lakes, mountains and ethnic groups, few of the leaders who shepherded Africa to independence a half-century ago wanted to tinker, because redrawing the map could be endless and contested. So, on May 25, 1963, when the Organization of African Unity was formed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, it immediately recognized the colonial-era borders. In hindsight, it is clear that the old boundaries often hurt prospects for state building. But back then, and even today for many Africans, the alternative of tiny ministates seemed even worse. “In 1963, the O.A.U. did something very important: they sanctified the borders,” said Sadiq al-Mahdi, one of the grandfathers of Sudan’s politics, a vibrant man in his 70s whom I recently interviewed in a gazebo along the Nile near Khartoum, with bowls of dates at his fingertips. “But now this sanctification is gone,” he said. “The borders have been polluted. And to resort to self-determination to solve your problems will break up the Sudan, will break up Ethiopia, will break up Uganda, will break up all of Africa, because all African countries are made up of such heterogeneous elements.” “Pandora’s box is now open,” he declared. Mr. Mahdi is understandably grumpy. For starters, he was an architect of the most brutal phase of the north-south civil war in Sudan in the late 1980s, and is widely blamed for unleashing tribal militias against southern civilians, an accusation he denies. (The tactic was repeated in the last decade in Darfur in the west.) Eventually, the southerners won. And now he, like many northern Sudanese, is as fearful and depressed as a patient about to undergo an amputation. If the southern third of Sudan is lopped off, with it goes most of Sudan’s oil. Even though much of that oil still must flow through the north in pipelines for export, northern Sudan is in for a rough patch, and Mr. Mahdi knows it. But divorce will also be messy for the south. It’s not as if there is a knife-sharp cultural line where northern Sudan ends and the south begins. The British colonizers did draw an administrative border. But many communities, like the Misseriya nomads, drift back and forth across that line to graze their animals, and the Misseriya are now refusing to be categorized as northern or southern. One of their areas, Abyei, is considered a likely flashpoint of any potential dispute over where to divide the country. Most Africa hands agree that there was considerable international pressure on the African Union, the successor to the Organization of African Unity, to make southern Sudan an exception to the rule about preserving old borders. “Recognition is seen as a very, very bitter pill” at the union’s headquarters, said William Reno, a political scientist at Northwestern University. And Phil Clark, a lecturer in international politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, said that until last year, “the A.U. mantra was that independence for the south would lead to further conflict.” But the African Union, which needs the West to finance its peacekeeping missions, yielded in the face of enormous American and European support for the southern Sudanese — support rooted in perceptions that southerners have long been Christian victims of Muslim persecutors. There was also the matter of Sudan’s president, Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who was indicted by the International Criminal Court on genocide charges for atrocities in Darfur. He is also suspected of reviving old contacts with the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda to destabilize southern Sudan. “Could it be that Bashir’s support for the L.R.A. and other rebels has made countries exhausted” with him, wondered Maina Kiai, a Kenyan human rights advocate. “Or could it be self-interest among the neighbors hoping to cash in on a new, unformed state that has plenty of natural resources? “I do think the oil could be a major factor,” he added, especially for Kenya, Uganda and perhaps Congo. (There has been talk of one day building a new pipeline through Kenya and Uganda that could let the south’s oil exports bypass the north.) Letting southern Sudan break free could also set a wide and unpredictable precedent — including for the Western Sahara, the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, the Cabinda enclave in Angola, and Congo. There is also Somaliland, the only functioning part of Somalia; it recently held elections followed by a peaceful transfer of power. Michael Clough, who directed the Africa program at the Council on Foreign Relations in the 1990s, said he thought that the African Union did not play the same influential role it once did. He expects that local balances of power, more than anything else, will determine whether a putative state like Somaliland actually becomes independent. When the union was founded in the 1960s, “there were a number of strong and articulate African leaders,” he said. “Today, I just don’t think there are many leaders left in Africa who have political/moral authority.” In other words, maybe Africa is moving toward an understanding that smaller units can be better — that the Pandora’s box should have been cracked open long ago and the colonial-era borders adjusted to carve out smaller, more governable units. Mr. Clark doesn’t buy it. “Africa doesn’t need a new map,” he said. “It needs new forms of leadership. In particular, it needs leaders who use national resources to benefit all citizens.” With that, Mr. Kiai agrees. In the end, the Kenyan human-rights advocate said, Africa’s problems are about governance and “the narrative of the state.” “No country becomes a nation without a common accepted narrative that goes beyond individuals,” he said. “Hence the U.S. and its Mayflower, Tea Party, the War of Independence, the Wild West stories. When there is a narrative that provides a sense of sharedness, then the sense of nationhood cements itself.” By that standard, though, maybe an independent South Sudan won’t be a struggling nation-state either. True, it’s poor, even by African standards. Many children go to school under trees. Many local officials can’t read. But if it has anything, it is a sense of “sharedness” — of shared sacrifice and shared struggle. Maybe that means more than roads. Or oil.

| ||