Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Elegy to Parvathi Ammaby Sachi Sri Kantha, February 27, 2011

A Bhagavad Gita sloka says:

In Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’s English translation, this sloka means “When the Lord takes up a body and when he leaves it, he takes these (the senses and mind) and goes even as the wind carries perfumes from their places.”

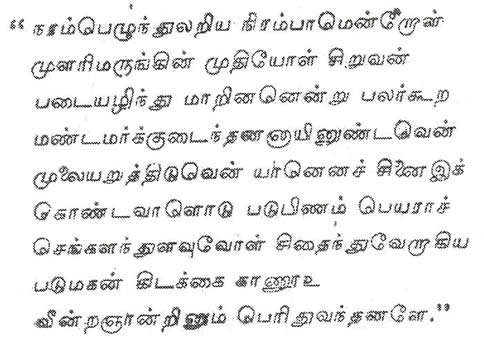

Whatever the desecration, the military minions of President Mahinda Rajapaksa meant to hurt the feelings of Eelam Tamils, we can feel encouraged that Mrs. Parvathi Veluppillai’s (1931-2011) mortal ashes have been taken care of by the Lord. The action of military minions only demonstrates that she was a brave woman, who gave birth to a Tamil hero; even in death this lady scared the pants off culturally dumb idiots. Even with her ashes, the naked brain matter of these minions and their paymasters stand exposed to the world. It is apt to eulogize Parvathi Amma’s life with the famous, ancient Pura Nanooru song of the Tamil Sangam anthology, dedicated to brave mothers. Among the 400 songs [literally Puram = Exterior, Nanooru = 400], that describe Tamil life between 200 BC and AD 200, was this beautiful one with nine lines, which extols the courageous spirit of a hero’s mother. In English translation, it reads: “The old woman with lean, lanky shoulders and of slender waist on hearing from the lips of many that her son had turned his back on the battle field became enraged and pledging that If her son had been a coward while fighting, She would slice the very breasts which he sucked. Picked up a sword, went to the gory field turned over the corpses and finding her son’s wound in front became delighted than when she gave birth to him.”

It can be inferred that Tennent never got an opportunity to interact with the women of Valvettithurai. What he had portrayed was their external beauty of the body as a ‘tourist’. What the Valvettithurai women was blessed with in abundance was the internal beauty of pride, mental toughness, thrift and god-fearing spirit. And Parvathy Amma was an epitome of this. Born in 1931, she married young, around the age of 16 or 17. She probably would have had an elementary school education. She gave birth to her fourth child Pirabhakaran on November 26, 1954, at the age of 23. An Indian reporter who approached her in 1995, when she was living in Tiruchi, Tamil Nadu, had described her mood and surroundings as follows:

Yes, Parvathi Amma was a tough lady indeed. That toughness and pride was evident last year, when she rejected a belated, half-hearted offer by the Indian mandarins to let her receive medical treatment. She would have found it insulting to the pride of Valvettiturai and Tamil courage. She could not boast of a MBBS degree, a JD degree from Harvard or a PhD from a European university. But blessed with an elementary school education in Vadamarachchy area, Parvathy Amma showed what simple common sense, toughness and pride means in this world. She might be illiterate in English and did not see America during her high school days and return to Sri Lanka to stage and act in the translated Tamil plays of Tennessee Williams; but Parvathy Amma was a real heroine in many dramas which were staged in Eelam territory during our times. When I wrote ‘Pirabhakaran Phenomenon’ (2005), which was first serialized in this website from 2001 to 2003, I deliberately omitted references to living individuals. Thus, you won’t find any references in it to Prabhakaran’s parents, siblings, as well as many other LTTE top rankers (such as Anton Balasingham, S.P. Thamilchelvan), who were living then. I included only one sentence about Parvathi Amma, which was “Pirabhakaran’s parents have been described by pestering reporters who had approached them, as ones who won’t wilt even under discomfort and pressure.” I provide a contemporary eulogy to another heroic mother (from a 63-year old Japanese woman Chiyo Taniguchi) who lost her son in the Second World War. These lines also fit our sentiments about Parvathi Amma. In English translation, this elegy of four lines read as follows: “Mom, when brother was killed in the war, You didn’t show your tears in public. When and where did you weep?” Finally, I also like to cite some sentences from the sentiments expressed by humorist Andy Rooney, on the death of his mother. I think, these also fit to Parvathy Amma perfectly.

Sources Maruoka-cho Cultural Foundation: Japan’s Best ‘Short Letters to Mom’ – The Best 51 Letters, Kadokawa Shoten, Tokyo, 1995, p. 118. X.S. Thani Nayagam: Landscape and Poetry – A Study of Nature in Classical Tamil Poetry. Asia Publishing House, New York, 1966. Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam: Ancient Jaffna. Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 2003 reprint (originally published in 1926), p. 144. S. Radhakrishnan: Bhagavad Gita. Harper Collins, New Delhi, 2000 Impression (originally published in 1948), p. 329. Andrew A. Rooney: And More by Andy Rooney. Athenum, New York, 1982, pp. 240-242. G.C. Shekhar: Pirabhakaran’s Parents: In the name of the son. India Today, Dec. 15, 11995, p. 31. Sachi Sri Kantha: Pirabhakaran Phenomenon, Lively COMET Imprint, Gifu City, Japan, 2005, p. 389. James Emerson Tennent: Ceylon, vol.II, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, 1999, pp.535-536 (originally published by Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, London, 1859, 2nd ed.) |

|||

|

||||

When Sir Emerson Tennent, the 19th century British administrator and historian passed through the Point Pedro-Valvettiturai area 160 years ago, he was impressed by the women folks of the Valvettiturai coast. This is what he had described in his classic work, Ceylon (1859).

When Sir Emerson Tennent, the 19th century British administrator and historian passed through the Point Pedro-Valvettiturai area 160 years ago, he was impressed by the women folks of the Valvettiturai coast. This is what he had described in his classic work, Ceylon (1859).