Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Satyagraha of March 1961 in Eelamby S. Ponniah, 1963

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha Comparing the Federal Party’s nonviolent campaign led by S.J.V. Chelvanayakam in 1961 to that of the LTTE’s violent campaign led by V. Prabhakaran since 1980s is of interest. Here are my nine observations. First, there was no interference from nosy external forces (especially the RAW intelligence operatives from neighboring India, Pakistan’s military mercenaries, Britain’s Special Air Service (SAS) mercenaries, Israel’s MOSSAD operatives) in 1961. RAW was formed only in 1968. But this was not to be during LTTE’s campaign from 1980s. Since 1982, RAW and Pakistan’s mercenaries from military dictators Zia Ul Haq and Pervez Musharaff had been a threatening presence to Eelam Tamil interests.

Secondly, the international human-rights industry and their local lackeys (the likes of Hoole brothers, Jehan Perera) were absent in 1961. Amnesty International was founded in July 1961 in UK. Human Rights Watch was founded in 1978 in New York, under the name Helsinki Watch. The Amnesty International became interested in Ceylon, after the April 1971 JVP terrorism. Though some Tamils have soft feelings to the activities of Amnesty International, I’m not convinced. My view is that this brand of Human Rights barking are self-serving and they only serve the interests of super powers in intelligence gathering. They are also semi-blind to the naked terrorism of the state. Pampering by the international human rights barkers was a Pandora’s Box to Tamils. Thirdly, in 1961, the local press owned by Sinhala moguls [The Lake (Fake) House, as well as M.D. Gunasena and Davasa groups] from Colombo, Sinhalese intelligentsia (with a few notable exceptions) and Buddhist clergy were highly critical on Federal Party leadership, even though the agitation for Tamil rights was strictly of a nonviolent nature. This remained a constant during the LTTE’s campaign as well. Fourthly, among Tamils, there were (are) shameless sycophants who sided with SLFP regime of the day. Alfred Duraiappah (then the Independent MP for Jaffna) was one of them in 1960s. Chelliah Kumarasuriar, K.T. Rajasingham and K. Vinodhan in 1970s, as well as Lakshman Kadirgamar and Douglas Devananda were 'Duraiappahs' in 1990s and 2000s, and were Duraiappah’s professional descendants. Fifthly, among Tamils, some politicians who came to prominence among Sinhalese since 2004 by criticising the LTTE for its violent campaigns (the likes of Veerasingham Anandasangaree!) were conspicuously absent in nonviolent satyagraha campaign in 1961. At that time, Anandasangaree belonged to the Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaja Party. Sixthly, Uncle Sam was busy in 1961 with Cold War politics and toppling Fidel Castro from Cuba. He was least bothered with what was happening in Ceylon. But, this was not so after the end of Cold War in 1990s and 2000s. Seventhly, while Chelvanayakam led the satyagrahis in 1961, his wayward son S.C. Chandrahasan has colluded with India’s RAW panjandrums since 1983 to undermine the spirit of Eelam Tamil liberation. The same would be noted for Chelvanayakam’s protégé Senator M. Tiruchelvam too. His son Neelan Tiruchelvam was neck deep in his ties to anti-Tamil interests in Colombo and in Washington DC. Eightly, journalists' panjandrums, servicing the enemies of Eelam Tamil political aspirations, were mild in 1961. But this was not so from 1984-2009. In this respect, the anti-LTTE propaganda of D.B.S. Jeyaraj (Canada), Noel Nadesan (Australia), K.T. Rajasingham (Thailand), Rajeswary Balasubramaniam and Nirmala Rajasingham (UK) and Rohini Hensman (India) deserves mention for their twisted tripes. Ninethly, on a positive note, Eelam Tamils were happy with their leadership, irrespective to which religion or caste they belonged to, as long as the leader showed proper leadership traits. Federal Party’s leader Chelvanayakam was a minority Anglican Christian. LTTE’s leader Prabhakaran arose from fisher caste (karaiyaar; which literally means, ‘those who belong to the coasts’), and not from the Vellalar (farmer) caste.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Satyagraha campaign of the Federal Party, I have transcribed below Chapter 10: Satyagraha Continues Chapter 11: The Premier’s Broadcast: The Pros & Cons Chapter 12: Some Highlights of Satyagraha Chapter 13: Government’s Anti-Satyagraha Moves Chapter 14: The Premier Returns from Commonwealth Premiers’ Conference from S.Ponniah’s Satyagraha and The Freedom Movement of the Tamils in Ceylon (1963) book. These chapters cover the events of March 1961. The subtitles, within each chapter, are as in the original. Chapter 10: Satyagraha Continues (pp.86-94) The eleventh day of satyagraha at Jaffna on 2nd March, may be recorded as one of the greatest events in the history of Ceylon, on account of the spontaneous uprising of the Tamil-speaking people against the tyranny of the government of this country and its armed forces.

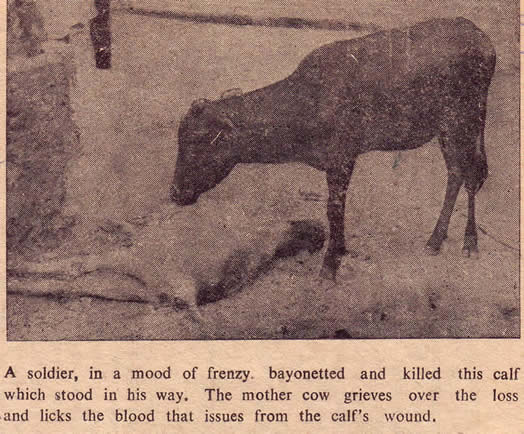

This officer was keen to get into the kachcheri. He secretly conveyed his wish to the Commanders present there. There were thousands of satyagrahis at the Main and Old Park entrances through which no entry would have been possible. The satyagrahis were suddenly taken aback, when they saw some military and police men lifting a man in white national clothes close to a parapet wall underneath which there were just a handful of satyagrahis. At once the Member for Nallur, Dr. E.M.V. Naganathan who was close by, learning that this person was Mr. N.Q. Dias rushed forward to prevent his ingress while a few other satyagrahis followed at his heels. As Mr. Dias was being held above the parapet wall, the satyagrahis intercepted the armed men and stood against the wall with upraised hands. This brought in more armed forces and satyagrahis. In the commotion that ensued, the armed forces attacked the satyagrahis with rifle butts and batons, but the satyagrahis stood up quietly. Dr. Naganathan was heavily baton-charged and attacked with rifle butts. As the armed forces struggled to life Mr. N.Q. Dias as high as possible, his legs got placed wide apart and his clothes, unable to meet with the distention gave way in two places. As the armed men dropped him, he fell with a heavy thud on the inner side of the wall in the kachcheri premises. He sprang to his feet, and with snarl, he stared at the armed men who had dropped him. But his stares fell on their backs, they having turned to the crowds. Similar experiences were gone through by Mr. Nissanka Wijeratne, the new acting government agent, a Sinhalese. While he attempted to secure entry into the kachcheri for the first time to assume duties on this day, i.e. 2nd March, satyagrahis at the Old Park entrance refused him entry. This led to a triangular charge on the satyagrahis by the police, army and navy. 17 satyagrahis sustained injuries and 5 of them were seriously injured. All of them were admitted to the Jaffna Hospital. Despite their assaults and bleeding injuries, the satyagrahis did not move from the entrances and still the new government agent was outside the entrances. In a couple of minutes of the assault the number of satyagrahis increased and this compelled the Forces to abandon their attempt to create an opening for the new government agent. A little later, as the satyagrahis lay prostrate on the ground, the police lifted him over their heads and dropped him over the parapet wall into the kachcheri premises. This happened at a place well away from the Old Park entrance and at spot where there were just a few satyagrahis who did not expect this. The entire scene was remarkable for the patience with which satyagrahis conducted themselves. They baffled all provocations and went through the tests gloriously and successfully. The armed forces little appreciated that they were dealing with disciplined and trained satyagrahis. Even the crowds had become somewhat disciplined on account of incessant appeals made to them by the Federal Party leaders that the people should not let down the satyagraha movement by any hasty and violent conduct or by doing anything on the impulse of the moment that would infringe on their avowed principles and methods. Seige and Counterseige About 400 satyagrahis at the kachcheri entrances were encircled by Navy men armed with bayonets and rifles. The satyagrahis who were encircled included some Federal Party Members of Parliament. They could not have contacts with the people outside. Neither food nor water could be taken to them. The navy and military refused to allow any people to serve the satyagrahis and the whole day they had to starve and suffer the agonies of thirst. The government plan was to starve the satyagrahis into submission and thereby break the movement. The siege of the satyagrahis by the armed forces came as a shock to the people, who on hearing this began to surge on the kachcheri in thousands. As the crowds kept on increasing the armed forces put a cordon to keep them off and prevent them from reaching the gates of the kachcheri. They impeded the normal run of affairs.. Traffic in the streets came to a standstill. Buses, lorries, cars, vans, carts etc. were all halted in never-ending lines throughout the steets and lanes of the city. Doctors and nurses were prevented from going to the hospital. They squatted on the middle of the road and refused to leave. Scavengers and street cleaners, too, were impeded in their normal duties. They halted their lorries and carts in the streets and squatted along with the others. Railway stations and railway lines became packed with satyagrahis. Train service was completely paralysed. Crowds Swell A postman, one Kandiah unmindful of the nature of the situation rode on his push-bike into the military cordon. He was bound for Chundikuli to deliver an urgent telegram. At once a naval soldier, in ‘rakshasa’ fashion, thrust his bayonet into the body of the postman who, having lost his balance fell, on the ground senseless, bleeding profusely. He was taken to the hospital. He was in a serious condition. The news of this heartless onslaught on the postman was received with much bitterness and resentment by the Tamil-speaking people in the peninsula. The postal workers of the Jaffna post office struck work at once as a protest against the assault on the postman. Other postal workers in the rest of the peninsula also struck work and this resulted in a complete paralysis of the postal service in this area. Immediately after this incident vast crowds of people flocked to the scene. All approach roads to the kachcheri became filled with people who had become hostile. These crowds encircled in turn those armed forces who had encircled the satyagrahis. These forces were disabled from having any access or contact with the remaining forces outside. In certain streets the people squatted even to half-a-mile deep. It was lunch time, but neither satyagrahis nor the armed forces had their lunch. In one street, at the tail-end of the crowds who were squatted, a military jeep and a military truck halted. The jeep had a high-ranking military personnel and the truck contained, besides a number of soldiers, food and other provisions for the Forces. The high-ranking, military officer and the soldiers in the jeep and truck got down with their bayonets and guns in a threatening manner and told the crowds to disperse. Heedlessly the crowds stuck to their places. Some of the soldiers attempted to pull away few of those who were squatted. At once hundreds of onlookers rushed to the spot and squatted. Then the military men got into their vehicles and threatened to drive through the crowds. At this stage the crowds, almost turned hostile and anything could have happened had it not been for the insistent appeals of some educated men to the crowds to follow the peaceful way of satyagraha. The high-ranking military officer again got down from the jeep and made an appeal to the crowds to make way for them as they were taking food. ‘Food to whom?’, asked a boy of 16. ‘Food for soldiers, please’, returned a soldier who was standing close by. ‘What about food for the peaceful satyagrahis?’ questioned the boy in a mood of frenzy and at the top of his voice and he quickly followed it up saying, ‘No food for satyagrahis, no food for soldiers’. This was echoed by the rest of the crowds and as they did so, they knitted themselves closely against the buffer of the jeep. Some stood up; some squatted, while others lay prostrate on the road. Close to the bumber tens of young men lay one upon the other. The people in front of both the jeep and truck were so packed that they gave the appearance of a hill grown with human beings rising tier upon tier. It was clear from the determination of the people that they were ready to face the consequences, even if it meant death. The soldiers stood confounded, but the high-ranking military person could not help betraying now and then smiles at the courageous conduct of the boy who was the spark and life-wire of the entire throng. It was with great difficulty that both the militarymen and their vehicles retraced their steps and disappeared. Almost a similar incident happened at the Ariya Kulaththady junction. At this spot there was a huge crowd. The three commanders of the Navy, Army and Police drove in a jeep and arrived at this junction. They were stopped by the people and refused further entry. They had to get down from the jeep and walk back to their places of calling. Heavily armed navy men stood on guard at the Chundikuli junction and prevented the people from going to the kachcheri. A contingent of boy students, in their determination to assert their freedom, lay prostrate on the roads at the junction. Some soldiers uttered threats and asked them to quit the place; but in vain. One soldier held his rifle point-blank against the boy’s chest and threatened to shoot him on the spot unless he got up and left the place. But the boy gallantly stretched his chest and said, ‘Here shoot if you must and I am ready to die.’ The soldier recoiled completely stupefied. Not less than a lakh of people had filled the kachcheri streets and lanes. Although there were only about 400 satyagrahis at the kachcheri entrances outside there were at least fifty thousand people who turned satyagrahis on the impulse of the moment which was brought about by the armed forces on account of their tactless and stupid handling of the situation. For about a mile in length the streets of Jaffna became packed with people, buses, lorries, vans, carts, jeeps and trucks. Traffic of all kinds came to a dead stop. It took hours and hours to clear this enormous congestion. This day at Batticaloa, about 1,500 satyagrahis squatted in front of the kachcheri. A large number of Muslims participated. The muslim MP for Kalmunai, Mr. Ahamed, in a written appeal requested all Muslims in the Battiacaloa and Kalmunai areas to sink their differences and join the satyagraha movement and render whatever help they could. There were about 400 women volunteers. Batticaloa Student’s Forum also participated. Sinhalese Satyagrahis Sinhalese residents of Batticaloa actively interested themselves in the satyagraha movement. They joined processions and uttered slogans against the government. They squatted in front of the kachcheri along with the Tamil-speaking satyagrahis. The leader of the group of Sinhalese satyagrahis remarked that insult to their Tamil brethren was insult to themselves as both were equal citizens of Ceylon. A number of wealthy Sinhalese residents served the satyagrahis for several days with lunch, fruits and drinks. They had also collected funds for the movement. Mr. B.R. Devarajan’s transfer from Batticaloa took effect from this day and the new government agent of Batticaloa, Mr. D. Liyanage arrived in the morning of the same day. It was well known that the reason for his transfer was unlike that of his Tamil counterpart in Jaffna, his courageous refusal to collaborate with the government to further the cause of violence on peaceful satyagrahis. At Batticaloa, resolutions were passed by the Urban Council and the Lawyers’ Association demanding the government to withdraw the armed forces from the Northern and Eastern provinces, if the government really wanted peace and to avert very serious consequences for the government and people of Ceylon. The Lawyers’ Association of Batticaloa also resolved to resist the implementation of the ‘Sinhala Only’ at whatever cost besides giving moral and pecuniary aid to the satyagraha movement. It lies to the credit of this Association to have been the first body of lawyers to take a dignified and clear stand on the language policy. The lawyers’ of Jaffna themselves would admit it, but with a sense of shame. It is, however, encouraging to see that the Jaffna Lawyers’ Association, too, at the present moment is viewing the language question with a measure of sternness that it never was accustomed to. They are now united to a man that besides resisting the implementation of the ‘Sinhala Only’ in the Northern and Eastern provinces Tamil should be the language of the judicial records in these provinces. There is now happy to relate, no denationalized Tamil in these regions with a wooden feeling so as to cause any damage or be a hinderance to our sacred and fundamental cause. On 3rd March, navy personnel who had been on duty for full 48 hours were completely withdrawn from the streets of Jaffna and the kachcheri entrances. The police and army took charge of the situation. The satyagrahis, who were squatted for the 48 hours at the kachcheri entrances without food or water and who refused to disperse despite enormous harassing from the armed forces, were relieved this day during the early hours of the morning by a fresh batch of satyagrahis. The performance of satyagraha for 48 hours without a break was due to the information received that the armed forces were going to occupy the kachcheri entrances and prevent satyagrahis reaching them. The armed forces also held out the hope to the government that they would pave the way for the public servants to go to their offices. Government sources claimed that the navy was withdrawn on the undertaking given by the Federal Party leaders that satyagrahis would not prevent the officers from going to their offices. Mr. S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, however, rejected this claim as untrue and mischievous. To the Tamils, it was clear that the government claim was without foundation as the Federal Party satyagraha movement was primarily intended to picket public servants from attending their offices and that such an undertaking would be incompatible with their strategy. Federal Party sources said that the navy personnel were withdrawn as the situation in Jaffna was ‘getting out of control with thousands of students and Federal Party volunteers appearing on the streets of Jaffna’. The people of Jaffna knew that the Federal Party claim was correct. After two days hurly-burly, satyagraha on 3rd March, commenced with marked calm. The golden rays of the early Sun peeped pleasantly through the green leaves of trees and dissolved the clouds of the peoples’ minds. The satyagraha had persisted and was continuing despite enormous odds. There was rejoicing in the whole of Jaffna. Although satyagrahis increased, there was no interference whatsoever from the armed forces. Satyagraha was performed throughout the whole day peacefully. Muslims’ Day March 3rd may be treated as the Muslims Day at Batticaloa. About 5,000 Muslims participated in the satyagraha in front of the Batticaloa kachcheri. Mr. Markan Markar, 2nd MP for Batticaloa issued an appeal to the Muslims of Batticaloa, Kattankudi, Eravur and other areas to support the satyagraha move and the demand for language and other basic rights. The Muslim Traders’ Association in a memorandum took up the position as follows: “So long as the Federal Party has pledged to secure for Tamil its honoured place, we the Muslims of Batticaloa are prepared to give the party our maximum support. The prime minister and the government must know that the Tamil question affects not merely the Tamils but the Muslims of Ceylon too. The prime minister must summon a roundtable conference without delay and settle the language problem satisfactorily.” All Muslim shops and business establishments were closed to enable the employees to participate in the procession. That day there were 25 processions of volunteers and supporters. The Batticaloa Students Forum organized a mammoth procession of students running in many thousands who paraded throughout the streets of Batticaloa displaying their health and vitality and their zeal for a magnanimous future. The heat of the day was so intense that a number of people including women and children fainted. Soda tea, coffee, young coconuts and meal packets were served in abundance. On 4th March at Trincomalee, satyagraha was started, led by Messers N.R. Rajavarothayam, MP and T.A. Ehamparam, MP for Mutur. As satyagrahis squatted at the kachcheri entrance and prevented public servants from entering the kachcheri, the police baton-charged them injuring 4 satyagrahis seriously and causing 6 others minor injuries. One of those seriously injured was Mr. Ehamparam, MP, who soon after developed complications of heart. In spite of the activities of the armed forces, satyagraha persisted. ***** Chapter 11: The Premier’s Broadcast: The Pros & Cons (pp.95-106)

In a broadcast on 4th March before her departure that day for the Commonwealth Premiers’ Conference in London, the prime minister urged the Federal Party to give up its satyagraha campaign. She was rather emphatic that no discussions would be possible until then. She guaranteed that if the Tamil people suffered any hardships owing to government’s language policy she was ready to consider them after her return from the London conference. Recounting the uses which Tamil enjoyed, the prime minister said:

While such reasonable steps have been taken to do justice to the Tamils, it is highly deplorable that a campaign calling itself satyagraha which is misleading the people and obstructing state business should have been started. I am certain that this is not a step that has the approval of the reasonably minded members of the Tamil community. It is said that nonviolence is the essence of any satyagraha movement. But the so-called satyagraha movement carried on by the Federal Party is by no means nonviolent. Last Thursday, a Federal Party member of parliament and his associates had attempted by use of force to prevent a highly paced government official entering the kachcheri premises. Last night I saw for myself the torn clothes of this official… It has been publicly declared that the campaign is aimed at preventing the implementation of the Official Language Act in the Northern and Eastern provinces. I should like to make it clear to the people that there will be no change in the implementation of the Official Language Act which, as everyone knows, was enacted on the request of the people and in accordance with a solemn pledge given to them at two successive general elections.” [dots as in the original.] These, were the chief matters she dealt with in a fairly long speech. One need not be at great pains to show how unfair and unjust the prime minister’s speech was to the Tamil speaking people. In the last paragraph the words “at the request of the people and in accordance with a solemn pledge given to them at two successive general elections” cannot fail to tell the world that it was a decision given by the Sinhalese majority against the Tamil-speaking minority and yet the prime minister and the government would have the world believe that the implementation of that policy is political and natural justice! What an unimaginative and unenlightened approach! Is this not enough to establish the fact that the prime minister and government were pursuing a policy of racial discrimination and persecution against the Tamil speaking people in this country? The Low-minded The prime minister had imputed violence to the satyagrahis! It could be countered by what the new government agent of Jaffna, Mr. Nissanka Wijeratne, a Sinhalese himself, who was unlike the prime minister, an eye witness to the conduct of the satyagrahis, had said of them: “The satyagrahis are very well behaved gentlemen”. He said this on 3rd March (Friday) and it was released in most of the newspapers in the island. But the mischievous purpose of the allegation by the prime minister was well known to the Tamil speaking people. Naturally, they did not bother about what the prime minister had said. Even “the reasonably minded members of the Tamil community” were well aware that there was no truth in the prime minister’s remark that the satyagraha campaign did not have their approval. What the prime minister had in her mind by those “reasonably minded members of the Tamil community” were the just few shameless and dastardly Tamil sycophants who were utter strangers to a sense of self-respect or dignity and ready to barter their inalienable rights for their selfish and temporary advantages. Their was one Tamil politician, particularly, who was content to wash the dirty linen of the Government’s military conduct, viz. its atrocities on the unarmed satyagrahis and expose the Tamils to ridicule and contempt by sheer betrayal. He also took great pains to give official functions at Jaffna, the appearance of success by entreating prominent Tamil men to be present at these functions! This man is satisfied with the crumbs and bones the Government throws! This estimation of the despicably low-minded individuals by the prime minister and her colleagues is shocking to the upright and decent people. What an understanding of human values! The time has now come even for the ‘fallen angels’ to restore themselves and find their honourable places. The fact that the prime minister on looking at some torn clothes in a remote place about 250 miles away from the scene of the incident was satisfied that they were torn by the satyagrahis is equally shocking to a person who had seen the incident with his own eyes. Thank God, the prime minister is not the judge. How many persons would have lost their rights, liberty and life! The satyagrahis did not do anything of that kind. The clothes of Mr. N.Q. Dias were torn, as the author has stated above, when the armed forces, in a frantic attempt, lifted him over the satyagrahis and the parapet wall to drop him in the kachcheri premises. Tamil Q.C.s Refute The arguments contained in the prime minister’s speech were adequately met and refuted by two eminent Tamil Senators, S. Nadesan QC and Mr. Tiruchelvam QC, in two of their most illuminating articles published in the Ceylon Observer. Mr. Nadesan wrote: “The most important basic right of a citizen is the right to his national culture. Ever since the first European war it has been widely recognized by most thinking people, that minorities must be protected against the danger of losing their national character and that an individual could not enjoy human rights in any meaningful sense unless adequate recognition was given to the ethnic collectivity of which he was an integral part. The Tamil speaking people consider that it will not be possible to preserve the Tamil language and culture in Ceylon unless there is firstly adequate recognition of the ethnic collectivity of which the Tamil-speaking citizen forms an integral part and secondly adequate use of the Tamil language in the day-to-day administration of those areas in which Tamil-speaking citizens are concentrated. This is the basic demand of the Tamil speaking people.” It has been stated that the Tamil language is now being used for the same purposes as it was under the British administration. Hardly anyone would disagree that those uses to which Tamil was put under the colonial administration were limited uses and that the full use of Tamil in keeping with a free language was never recognized under that administration. But due to the joint efforts of both the Sinhalese and Tamils, Ceylon today is free. With freedom to the Tamil-speaking people, to refuse the free and full use of Tamil in the administration of the country is what the Tamil-speaking people are aggrieved with. They had hoped that Tamil and Sinhalese would replace English and their honoured places would be regained. But now they are told that Tamil shall not regain that position, but Sinhalese only! Natural and elementary justice, however, would prompt to them that they are quite justified in insisting on their inalienable rights. Position Worse To be frank, the present communal government has made it worse for the Tamil speaking people. Whereas during the colonial regime name boards of post offices, police stations, railway stations, and of other departments were in English, Sinhalese and Tamil, is being eliminated in certain of the government departments presently Tamil. Even government frank and seals are maintained only in Sinhalese in all the departments. Reference has been made to the effect that provision existed for keeping a translation of the activities and report of the Sri Lanka Sahitya Mandalaya in Tamil. Actually, the reports are maintained by the Director of Cultural Affairs only in Sinhalese and English. This shows that unless statutory recognition is given to Tamil, the Tamil language runs the risk of losing its place in the administration of the country. Some capricious minister might come and inflict great hardships on the Tamil speaking minority. A true illustration may be given. In the past, the administration reports of government departments were published in all the three languages viz. English, Sinhala and Tamil. But now the present Minister of Justice has discontinued that practice. The Secretary to the Treasury issued a directive to all heads of departments that in future administration reports of government departments should be published in the official languge, i.e. Sinhalese, with an English translation. This directive, it was learnt, was issued on the instruction of the Minister of Justice. A Treasury spokesman said that the practice of translating administration reports into Tamil was followed even before the Official Languages Act was passed in 1956 and when English was the official language. Following the directive, heads of departments were compelled to take steps to discontinue the practice of translating these reports into Tamil. Speaking on this discriminatory act in the House of Representatives, Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, a leading Sinhalese Member of Parliament, said that the Tamil speaking people had every reason to live in fear and anxiety about their rights in this country, for the Government, by its obnoxious and communal acts like this forfeited the confidence the Tamil speaking people had placed in it. For quiet a long time Sinhalese and Tamil had been equal in status, but suddenly Sinhalese had been enthroned in a seat of power and prestige and Tamil neglected much to the annoyance of the Tamil speaking people. This could not promote communal harmony or good relations between the Sinhalese and Tamil communities, he warned. He exhorted the government to give Tamil its rightful place in the administration of the country. Provision was made even under the colonial administration for the use of Tamil in the Criminal and Civil Procedure Codes, viz. the use of Tamil in the duplicate of summons, proclamations of persons absconding, statements to magistrates and police officers, conditions of a probation Order, duplicate of plaint, notice of sale, giving evidence in Tamil, a Tamil-speaking jury and other similar matters. These uses were recognized not as a matter of necessity. For example, a witness who knows only Tamil can give evidence only in Tamil. I wonder whether a government can compel him to give evidence in any other language. That is the reason whcy a Tamil who knows only Tamil is given the right to give evidence in his language. A government that tells a Tamil that it has given him his freedom can as well say that it has given him the freedom to talk to his wife and children at home in Tamil. Surely, these uses of Tamil referred to by the prime minister are not the tests of a free language. The real test of a free language is the freedom given to those who speak it to use it in the manner they want; i.e., to suit their convenience, coupled with government patronage for its cultural and beneficial development. Great damage is done to community and the country as a whole when politicians and political parties make the language of that community a communal issue unleashing thereby a host of communal problems that undermine the social and economic structure of the nation. Herty writes: “Afterall, language is an instrument of citizenship and not a weapon of domination and consideration of prestige should not be allowed to prevail over the dictates of plain common sense. This problem can never be solved in an atmosphere of distrust or by veiled efforts by one nationality to dominate over others.” It is vital to know that inalienable, basic human rights far outweigh mere considerations of prestige. Minister’s Intransigence When the Minister of Justice introduced the Language of the Courts Bill in parliament, several of its members exhorted him to follow the British precedent in India and declare Tamil as the language of the Courts in Tamil areas. In British India, the government declared the language of the area in which a Court was situated as the language of that Court, although English was the official language. The judicial records of those Courts were kept in that language of the area. The provision suited the convenience of the people of India and saved considerable expense, time and trouble both to the government and the people. But the Justice Minister of this country dismissed this suggestion with callous indifference. Referring to this Senator S. Nadesan wrote as follows: “But unfortunately the Minister of Justice summarily turned down this reasonable suggestion. His intransigence on this matter is in no small measure responsible for the present acute tension that is prevailing among the Tamil-speaking people.” University Professors In a brilliant article on the language question written jointly by five Ceylon University professors and lecturers, all Sinhalese namely, Rev. Lakshman Wickremasinghe and Messers E.R. Saratchandra, G. Obesekera, V.E.A. Wickeramanayake and Ian Goonatilake, the following was included: “An examination of the Language of the Courts Act indicates that no provision has been made for court pleadings to be led and court proceedings to be recorded in the Tamil language in Northern and Eastern provinces where necessary. The opportunity to give evidence in the Tamil language in courts is not the granting of a right as some claim but merely the recognition of brute fact in the present circumstances. In clause 4 this Act, however, provision is made for the use of English language where necessary and for the translation of documents in the English language into Sinhala in order to safeguard the main provision of the Official Language Act. It is both fair and possible to make similar statutory provision for the use of Tamil language in court documents in the Northern and Eastern provinces where necessary, within the frame work of the Official Language Act. In not doing so now the government is providing a source of just grievances to the Tamils of these region.” Criticising the prime minister’s reference to the ‘peoples’ mandate’, those Men of Letters wrote: “It is a political wisdom which also pays heed to the words of Jefferson in his Essays on Freedom, namely that all too will bear in mind the sacred principle that though the will of the majority is to prevail in all cases that will to be rightful must be reasonable both to common sense and to the moral sense.” These men of learning and culture in their article exhorted the government not to treat lightly the satyagraha movement that had ‘so much mass support among the Tamils.’ Almost similar opinions were expressed by Mr. M.B. Ratnayake, an educated Sinhalese of Gunnepana. Besides, there was a host of other Sinhalese gentlemen who had unsparingly condemned the government for pursuing a communal policy of discrimination and making the whole country a cauldron bubbling with communal riots and chaos. Those who are familiar with legal practice know that, a litigant should go to a court of law to obtain justice with clean hands. The prime minister of Ceylon, Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike at the Commonwealth Premiers’ Conference in London condemned the apartheid policy of the South African government. But as she did so, she knew that at home (in Ceylon) injustice had been done by her and her government to the Tamil-speaking people, viz. their fundamental rights of language had been heartlessly denied. Dr. Verwoed, the South African prime minister, however, was equal to the occasion. In reply, he lashed out at the Ceylon prime minister and her government for pursuing an inhuman policy of persecution against the Tamil-speaking people and denying their basic rights which were not denied to anybody even by the South African government. It is a case of the pot calling the kettle black! All the nations of the Commonwealth knew the happenings in Ceylon. It was learnt that these nations had decided to watch further developments in Ceylon before they discussed the Ceylon Tamil question in the UN organization. Some members of the Commonwealth however are becoming convinced that Ceylon affairs are assuming such proportions that the Tamil question can no longer be reasonably solved by the communal governments of Ceylon, whose fairness and competence are very much in doubt. To this extent, they feel, that the Tamil question is ceasing to be a local question. A better reason, still, is the fact that that conflict is not merely between sections of one nation, but between two nations, the Sinhalese steam-roller majority on the one hand and the Tamil minority on the other. If this racial question is not a fit matter for the jurisdiction of the United Nation, one wonders what other problem is more fitting. Again when the prime minister participated in the Belgrade Conference in September purporting to contribute mite in defence of democracy and peace, Mr. W. Dahanayake, the well-known Sinhalese Member of Parliament, speaking in the House of Representatives on September 16th, said that it was ridiculous that the prime minister of Ceylon was speaking glibly of the importance and defence of peace and democracy abroad while what was happening at home was just the opposite of democracy. Dr. N.M. Perera, Member of Parliament, also warned the House and the country that there was a serious threat to democracy in this country. The leading newspapers of the world had given prominence to the Ceylon Tamil question and had entertained the feat that the Ceylon government would not solve this question with fairness and justice. Let us see what the Madras Hindu, a newspaper that enjoys a reputation for its fair comment and unbiased views, had expressed on this question, in its editorial of 18th March. “We note that the finance minister of the Ceylon has lost no time in repudiating the South African prime minister’s charges against the government of Ceylon. Mr. Felix Bandaranaike says that there is no racial discrimination in this country. How then should one describe a policy whose sole effect would be to enthrone one race, one language and one religion above others and that would deny citizenship to the hundreds of thousands of Ceylonese of Indian origin, on the most flimsy grounds.” It is as though a duel between a giant and a pigmy. The little man is dragged, mauled and trodden by the heartless giant. Is there the man who would say ‘Go ahead’ to this giant who tells humanity, ‘You shall not interfere, for this man is in my territory, in my dungeon.” In Ceylon, nine trade union organizations protested to the prime minister on 3rd March against the use of troops on satyagrahis. Their resolution was as follows: “The working people in general and the organized trade unions movement in particular have long experience of the evils attendant upon the use of troops in relation to legitimate trade union activity. In view of this working people are restless over the deployment of troops in relation to the present situation which had resulted from the satyagraha campaign and the government policy towards it. The Coordinating Committee of trade union organizations also stresses that the present situation prevents the government and the people from engaging unitedly in the urgent task of bringing down the cost of living, abolishing unemployment and engaging in the planned development of the economy of the country. The Coordinating Committee of the trade union organizations notes with concern that, for instance the legitimate activities of the Government Clerical Service Union and other unions have been directly interfered with by the bringing in of troops.” The Unions which met and passed the resolution were the Ceylon Mercantile Union, The All-Ceylon Bank Employee’s Union, the Colombo Municipal Employees Union, the Trade Union Federation, the Customs Officers Association, the Ceylon Workers Congress, the Government Workers’ Trade Union Federation, the Governement Clerical Service Union and the Ceylon Federation of Labour.” On 9th March, 21 Government Service Unions at Jaffna struck work. This was a day’s token strike as a protest against the police atrocities. They also insisted on three things, viz. (a) withdrawal of Forces from the North and East; (b) an immediate inquiry into the assault on public servants by police, and (c) inquiry into the assault on the postman Kandiah by navy personnel. ***** Chapter 12: Some Highlights of Satyagraha (pp.106-123)

In a matter of few days, it became clear to all that the satyagrahis were solemnly devoted to their cause and strove hard to avoid violence. They had defied all forms of provocation by government and its armed forces. The prime minister’s allegations that the ‘Satyagraha campaign carried on by the Federal Party is by no means nonviolent’ came as a rude shock to the people of Jaffna. They, however, came to realise that it was intended to mislead the people. The prime minister’s broadcast had made one thing clear to the Tamil-speaking people; that the government was not willing to recognize their substantive rights. This led to huge rallies at the Jaffna kachcheri by Tamil speaking people of all descriptions regardless of their differences in support of the Federal Party satyagraha campaign. It did not matter whether they were Hindus, Christians or Muslims. Between 4th March and 18th April, all sections of the Tamil speaking people representing all their interests, viz. city-fathers, farmers, taxi drivers, carters, city workers, the clergy, Hindu priests, teachers, students, lawyers, doctors and politicians notwithstanding their party differences marched in processions carrying placards, uttering slogans and finally participating in the satyagraha. It was the decision of the Federal Party or other Tamil party. But as the satyagrahis rose to thousands everyday, this system had to be abandoned. The satyagraha movement became a spontaneous mass movement beyond party considerations. At this stage, the Member of Parliament for Udupiddy (Tamil Congress member) Mr. M. Sivasithamparam came into the movement with his party supporters. The government’s language policy and its excesses had driven the Tamil speaking people into one unified front. Teachers The Director of Education issued a circular that teachers of the Assisted Schools that had come under the Director’s management should not participate in the Federal Party’s satyagraha campaign and that all those who did participate would be discontinued from service. The Tamil Teachers’ Association of the Eastern Province criticized the Director for his circular and telegraphed to him to withdraw his circular at once pointing out that the circular was calculated to deprive the teachers of their political rights. Similar resolutions were passed by the Northern Province Teachers Association and the Hatton Tamil Teachers Association. As a protest to this circular about 400 teachers in the Eastern Province marched in procession on 4th March to the Batticaloa kachcheri carrying placards and uttering slogans. Many placards they carried indicated ‘Hands off Teachers Political Rights’. As the procession ended at the kachcheri entrances, the teachers joined the satyagrahis. Most of the satyagrahis that day were Muslims of the Eastern Province and they were led by the Muslim Member of Parliament of the Batticaloa constituency. At a meeting of 15,000, the Member of Parliament addressed as follows: “In the Tamil freedom struggle, the Muslims of Ceylon have a big part to play. What is wanted now is real unity between the Muslims and Tamils and I am glad that unity is forthcoming and is spontaneous. Once we have become strongly united, the government cannot but bow down to our demands.” The expression of his sentiments was acclaimed with thunderous applause. Another prominent Muslim of the Eastern Province observed, “What is the use of listening to those Muslims who pretend to be our leaders and talk softly of goodwill and alliance with the communal government when out own correspondence in Tamil with the government is replied in Sinhalese.” On 11th March about 3,000 teachers of both sexes from several parts of the Northern Province marched in a lengthy procession to the Jaffna kachcheri. They were dressed in white and the procession moved slowly. The entire scene resembled a slow-moving film of beautiful white figures in two rows. The placards they carried presented interesting and stirring reading. Some of them read as follows: TAMIL IS OUR SOUL TAMIL IS OUR LIFE BLOOD TAMIL IS MORE PRECIOUS THAN OUR EYES THOU SHALT NOT DEFILE OUR MOTHER TAMIL At the head of the procession they carried a painted canvas wherein was a picture of ‘Mother Tamil’ whose hands and feet were bound in chains standing with disheveled hair and dark and pitiful countenance. The teachers carried hundreds of black flags and uttered slogans in a studiedly rhythmical fashion that sounded pleasantly to the hearers. This slow-moving mile long procession took place against a cloudless sky and blazing Sun and lasted nearly one hour. When this procession approached the kachcheri entrances, a good number of teachers squatted at the entrances that were already packed with about 5,000 satyagrahis. They looked fatigued and there was almost a mad scramble to serve them with water, soda and young coconut. When the procession was over they placed the painted canvas representing ‘Mother Tamil’ at the main entrance to the kachcheri. Crowds of people collected there to get a view of this picture. The crowds included two Europeans. They were seen looking at this picture intently and talking to each other and appeared quite moved by what they saw. They then, came out of the crowds and talked to the people. At the end of their talk one of them was heard to say with a smile that betrayed a note of sympathy. “Your cause is just and your efforts cannot be without happy result. Any government that has the good of the governed at heart must soon yield to your demands. God bless you.” This day, i.e. 11th March, being a Saturday, the number of satyagrahis rose to nearly 8,000 while the crowds of sympathizers to about 40,000. In the ranks of the satyagrahis could be seen mothers with their innocent babes sleeping on their shoulders or laps as they kept singing devotional songs. There were old people of both sexes who had joined the satyagraha movement despite their failing health. Even sick people had abandoned their beds before their prescribed time to go to the kachcheri to satisfy their passion for satyagraha. Satyagrahis from distant places of the Jaffna peninsula walked in the hot Sun nearly 15 to 20 miles to participate in the satyagraha. Students Thousands and thousands of students of the North and East played a big part in organizing demonstrations and offering passive resistance to violence by the government and its armed forces. The assault on the satyagrahis by the police on 20th February came as a rude shock to the school children in the Northern province. Hundreds of students gave up attending school and went to see for themselves what was happening at the kachcheri. A large number of them mobbed the hospital verandhas and wards to get a good view of those patriotic Tamils who had sacrificed their blood for the Tamil cause. A teenage boy lost control of himself and broke into tears as he (talked) to a satyagrahi who was suffering from intense pain and difficulty in breathing, having been trampled on his abdomen by the police. There were many such pitiful sights and many students went without lunch on account of the depressing and melancholy effect of what they saw. On the following day, i.e., 21st February, about 5,000 students of the leading colleges of Jaffna marched in a long procession to the kachcheri which was about a mile and a half away as a protest against police violence. They marched in two columns winding through the streets and lanes. At the rear of the procession there were about a thousand cyclists who exhibited great skill in the art of balancing in a slow ride. The students carried black flags and placards. Their resounding slogans could be heart half-a-mile away. Many colleges had to be closed at noon for want of sufficient attendance. At the end of their procession, they wanted to participate in the satyagraha. But the Federal leaders and elders persuaded them not to participate as that would interfere with their studies and school discipline. They obeyed but assembled in front of the kachcheri entrances in large numbers and remained there until they were led away. There was also a long procession of girl students of about 5,000 from the schools and colleges of Jaffna. They collected in the premises of the Jaffna town hall and filed themselves in two long columns. Most of them were dressed in white frock while the rest were in glistening white sarees. They carried black flags and placards. Uttering slogans they moved beautifully through the streets and lanes of Jaffna and reached the kachcheri. On 25th February, 20 law students from the Law College headed a procession of school boys and participated in the satyagraha. Following the participation of the students of the North in the satyagraha movement, the Ministry of Education issued a directive over radio on 1st March 1961 to the heads of schools in the Northern province directing them to dismiss the students who absented themselves from school without sufficient reason. The parents of Jaffna treated this directive as an insult and a challenge to their liberties. Some of the leading parents met on 2nd March 1961 and issued a notice by which they requested all parents to stop sending their children to schools on 3rd March 1961. They however, appealed to the students not to participate in processions etc. This notice was widely circulated. As expected, not a single school, whether big or small, was able to function throughout the whole of the Northern province. Instead of confining themselves to their homes, the students organized demonstations and marched in procession all over the peninsula. They squatted at entrances to their respective schools and picketed teachers from attending them. The students strike spread to the Eastern province as well. Although, it was decided to be a day’s token strike, in the majority of schools, the students’ strike went on for a week. This inevitably compelled the Father of the Movement, Mr. S.J.V. Chelvanayakam to issue a general appeal to students to call off their strike and attend school. They responded to the appeal but not with a willing heart. On 3rd March at Batticaloa, thousands of students both boys and girls, marched in a huge procession and participated in the satyagraha at the Batticaloa kachcheri. It was organized chiefly by the Batticaloa Students’ Forum. All the school were closed for want of attendance. Students picketed teachers from attending schools. At the end of the procession, they joined the satyagrahis who were seated in the burning mid-day Sun. Unable to bear the heat, three girls fainted and had to be helped out. On April 6th some students marched to the tomb of Rajendra Stephen, who was killed by the military in the 1958 riots, pierced their forearms with knives and wrote in blood their determination to fight for Tamil rights. Similar processions were organized by students at Trincomalee, Vavuniya and Mannar. At Trincomalee, students invaded the police station as a protest against the police taking 3 students to the police station. They refused to disperse until the 3 students were released. The longest procession of students in Jaffna was on March 7th when nearly 10,000 students participated. Many hundreds of them went with their hands chained and with black handkerchiefs tied firmly over their mouths as an indication of the agony of the Tamils who are under chains and without freedom of speech. The provocation for such a procession was a rumour that Mr. N.Q. Dias, a senior civil servant of the government, was coming to open the kachcheri for work. Mr. Dias came to Jaffna but could not enter the kachcheri as he had to cross many columns deep of satyagrahis who numbered that day about 10,000. On 8th April, the Federal Party nonviolent service corps came out on a parade and marched in a procession to the Jaffna kachcheri. This service corps consisted mainly of the youth, both male and female and counted six hundred. They were mostly students. The lads were dressed in pure white with Gandhi caps. They formed one of the two columns of the procession. The other column consisted of young women dressed exquisitely in bright white blouse and saree and fringed in peacock blue. The entire youth wore on their chests the party badge of yellow, red and green. Both the youth and their wear shone pleasantly in the early rays of the Sun as they assembled and stood in the open space. The procession started from the premises of the ancient residence of the Tamil king Sankili, at Nallur. In front of the procession was a car fixed with loudspeakers amplifying the service hymn sung melodiously. Immediately behind the car were two motor cyclists, also dressed in shining white and smartly seated on their motor cycles on each of which was hoisted the party flag. After them the members of the service corps lined up in two columns. Their smart appearance in their white uniform, their brisk walk with regular steps against the background of rhythmic music was a rare sight, pleasant and captivating, that baffles description. Police and lorry-loads of army personnel in their rounds, apart from having a long and appreciative look at the procession, spontaneously moved their vehicles to a side to make way for the procession. Foreign observers, viz. Englishmen, Germans, Indians and even Sinhalese Members of Parliament who had come to gather first hand information about satyagraha had a full view of this procession and were highly impressed with it. When the procession was over these 600 lads and lasses participated in the satyagraha in front of the kachcheri. Lawyers The first group of lawyers to react to the Language and the Courts Act and the police violence on satyagrahis was the Lawyers’ Association of Batticaloa. By an earlier resolution, the lawyers of Batticaloa decided to resist the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act. As a mark of their decision to resist, they unanimously stayed away from the Courts for a full day. These lawyers of Batticaloa met again on 3rd March and passed a resolution calling upon the government to withdraw the armed forces from the North and East. They also resolved to support the satyagraha movement and give all possible financial aid. They did not merely pass a resolution but at once went into nonviolent action in furtherance of their resolution. At Jaffna on the other hand, there was no concerted action. On 8th March, the Minister of Justice was expected to come to Jaffna. This day about 35 lawyers of Jaffna marched in a procession and joined the satyagrahis. They were in the black coats and trousers. They lawyers included veterans. They came early morning and squatted till it was past noon intending to meet the Minister if possible and tell him their view of the Language of the Courts Act. There were about 10,000 satyagrahis at the entrances. That day the satyagrahis were led by Mr. S. Kathiravelpillai, advocate. A few days later the lawyers of Point Pedro went in a procession and participated in the satyagraha. They were led by Mr. Mailvaganam, the President of the Point Pedro lawyers association. They were dressed in their black coats and trousers. They squatted at the kachcheri until it was late in the evening. At Trincomalee, the lawyers marched in procession and joined the ranks of the satyagrahis at the kachcheri. They too went in their lawyers’ dress. Doctors Doctors, apothecaries, nurses and attendants too identified themselves with the satyagraha movement. On 2nd March when the armed forces interfered with free movement of traffic, doctors and nurses of the Jaffna hospital joined the crowds of people and squatted on the road and refused to move. Traders The Traders’ Association of Jaffna met and decided to go in a procession on March 8th. It was said that this day the Minister of Justice and two Members of Parliament from south Ceylon would arrive at Jaffna to study the situation. In view of this, thousands of people had flocked to the kachcheri. There were numerous processions from all parts of Jaffna. The most impressive procession of the day was by the traders of Jaffna. All shops, banks and business establishments were closed and no business of any sort was transacted in the whole of Jaffna city which appeared to be a deserted place. More than 5,000 traders participated in the procession. They carried black flags and placards. They also took with them big parcels of biscuits, sugar candies and a lorry-load of bananas and aerated waters to feed the satyagrahiss. When the procession ended the majority of them participated in the satyagraha while the rest started serving the satyagrahis with refreshments. A purse of Rs. 40,000 was given to Mr. S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, on behalf of the Jaffna Traders’ Association. At noon a lorry-load of lunch packets arrived for distribution among the satyagrahis, said to have been sent by some traders. Traders took turns to provide lunch packets until the emergency was declared. In this not an insignificant part was played by the Muslim Traders of Jaffna. Farmers Farmers from all parts of Jaffna peninsula actively participated in the movement. Various villages organized processions. These processions were as interesting as they were important. On 1st March a procession of bullock carts from Chunnakam arrived at the kachcheri. There were 50 bullock carts and they were filled with provisions for the satyagrahis – vegetables, fruits, yams and young coconuts and on these heaps were seated the farmers. In one of the carts was seated a blind old man of 70. Throughout the procession, he kept himself active. He sang and narrated stories. His main theme was Mother Earth. He did not fail to place her in the forefront of all other things. One of his exclamations was: ‘Oh! Mother Earth – How faithful and true you are. You are the only one in this world that has not betrayed us in life. How can we repay you?’ Village songs were sung and they were full with matter or thought-provoking ideas. One of such songs went thus: “We (farmers) bring you no ill will, no disease, no ingratitude, but the bounties of our Mother Earth, food, clothing and shelter nay more than that we bring you freedom too”. Many songs were of current topics. They scoffed at white collar jobs as servile and shaky and bereft of the essence of life, namely freedom-sweet freedom; they considered jobs as mere trifles that no self-respecting man would bargain for his human and basic rights, viz. language etc. Several songs ended with a warning and an appeal by the farmers to all others: “Come, come and toil with us and make sure for a free life”. As the procession ended at the kachcheri, the farmers got down from their carts and squatted at the entrance. On 15th March, a hundred tractors and lorries with more than 200 farmers and labourers set out early morning from the Kandaswamy Kovil at Kilinochchi, a distance of 50 miles from Jaffna. They brought with them rice, vegetables, fruits and green coconuts for the satyagrahis. All of them got down at the Jaffna esplanade and walked in procession to the kachcheri headed by their Member of Parliament, Mr. A. Sivasundaram. They carried with them, as they went in procession, parcels of rice and vegetables on their shoulders and heads. Young mothers carried their little children in their arms. In the hot Sun, as perspiration ran all over their bodies, they reached the kachcheri and swelled the ranks of the satyagrahis. They were received at the kachcheri by Mr. S.J.V.Chelvanayakam. The satyagrahis, that day, were led by Senator S.Nalliah and the deputy mayor. The Kilinochchi procession, too laid a strong emphasis that the life of the Tamil people should change from white collar jobs to an agricultural and industrial life. Clergy The Hindu and Christian priests had their turn at the kachcheri. The Christian priests accompanied by hundreds of Christians, both Catholics and Protestants, went in a procession and participated in the satyagraha. The procession included a large number of Christian women. As soon as they reached the kachcheri the priests and their followers started satyagraha by kneeling down in prayer. They spent the whole day in fasting and singing hymns in chorus. The Christians of Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Mannar and Vavuniya also displayed great enthusiasm for satyagraha. Brahmins On 13th March, the Brahmins of the All Ceylon Brahmin Priests’ Association, their wives and children came out in a procession, singing vedic hymns. Group singing, viz. bajanai, was the regular feature of their procession and satyagraha. They sang Thiruvasagam and Thiruvembavai of the Saiva saint Manikavasagar. They moved the hearts of all. The Brahmin priests were accompanied by a number of musicians who, melodiously sang and played on the flutes and violins. Apart from the stillness and ecstasy that prevailed on the advent of Brahmins and musicians, the atmosphere at the kachcheri became cleansed into one of purity and piety. The Brahmins blessed the movement and satyagrahis. Jaffna, that had not any shower of rainfall for the season, had a shower of rainfall within an hour of their advent. Notwithstanding the welcome shower, the satyagrahis (including women who had by now outnumbered the men satyagrahis) did not even make a stir, but sat quietly and determinedly. Mr. Chelvanayakam presided over that day’s satyagraha. The women satyagrahis were headed by Mrs. Chelvanayakam. Later in April, the brahmin priests of North Ceylon assembled at Punguduthivu and performed a yagam for five days at Sithivinayagar kovil. In olden times, kings used to offer sacrifices to the gods to end droughts, famine and pestilence. This was also performed by kings, who were without issues, to invoke the gods to bless them with children to succeed as heirs to the throne. The chief aspect of the yagam is making offerings to the gods accompanied by poojas invoking elaborate rituals. This was an expensive item. In the performance of the yagam at Punguduthivu, the priests paid due attention to rituals. This was accompanied with fasting and prayers by the participants. Thousands of people gathered everyday to witness it and joined the priests in their prayers to the gods for a solution of the Tamil question. At the end of the yagam, the priests went in a procession to the kachcheri chanting haro hara. They carried aloft Lord Muruga’s flag of the cock and peacock. As the procession ended, they served the satyagrahis with holy ash and holy water, a practice of the Hindus symbolizing their worship and faith in the gods. Taxi Drivers On 24th February, more tha a hundred taxi cars were driven in a procession through the streets of Jaffna and then to the kachcheri in support of the satyagraha campaign and as a protest against the violence inflicted by police on the satyagrahis. The taxi drivers who were compelled by government to use ‘Sinhala Sri’ on their number plates replaced by ‘Tamil Sri’ in breach of the law, hoisted black flags on one side of their cars and the Federal Party flag on the other and fixed placards, both in front and rear of their cars. The procession was witnessed by about 50,000 people and the taxi drivers were cheered as they drove through the streets. The taxi cabs’ procession evoked considerable interest and attracted large crowds as it was a direct challenge to the implementation of the ‘Sinhala Only Act’ in the Tamil areas. Consequent on this procession, the police took details of those cabs that had ‘Tamil Sri’ number plate and delayed both the driver and his car for a number of hours. Thereafter the police took away six cars without the knowledge of the owners. The reason given by the police for this was that the Superintendent of Police had instructed them to detain the cars with ‘Tamil Sri’. As a protest against this detention, more than 100 taxi drivers with their taxi cars bearing ‘Tamil Sri’ lined up at the grand bazaar and refused to move away. Following the great lea given by the taxi drivers more than 95 percent of the vehicles in Jaffna started plying with ‘Tamil Sri’ on their number plates. Following the detention, the owners of the six cars brought a criminal action against the police officers who took them charging them with theft in the magistrate’s court of Jaffna. The case, however, did not go through a full trial, but by way of settlement, the owners of the vehicles were allowed to take them away and the accused were discharged. Sinhalese Not an insignificant part was played by the Sinhalese residents of the North and East. Far from standing aside or contemptuously watching the satyagraha campaign or adopting a neutral attitude, the Sinhalese residents of Jaffna took an active interest in furthering the cause of satyagraha. The first contingent of Sinhalese in Jaffna participated in the satyagraha on 28th February. It included a number of Sinhalese women. Besides participating in the satyagraha, a good many of them served the satyagrahis with thousands of lunch packets, fruits and soft drinks. A leading Sinhalese satyagrahi remarked that the government’s activities were certainly communal and amounted to dividing the peoples of the country. He appealed to the government that it was nothing but just to concede to the Tamils their fundamental rights which the Sinhalese citizens themselves enjoyed in this country. On subsequent days more and more Sinhalese came into the movement. They also gave cash donations to the leaders of the movement. At Batticaloa on 7th March, a large number of Sinhalese went in a procession and participated in the satyagraha at the kachcheri. They carried black flags and uttered slogans calling for Tamil-Sinhalese unity. They blamed the government for all the communal trouble in the country. Sinhalese residents of Akkaraipattu and Nintavoor also identified themselves with the satyagraha movement. Sinhalese women satyagrahis were headed by one R. Alice Nona. Despite inclement weather, Sinhalese women with their babes in their arms, joined the ranks of satyagrahis. Certain wealthy Sinhalese served the satyagrahis with lunch, besides giving cash donations. At Trincomalee and Vavuniya, greater numbers of Sinhalese people participated in the satyagraha. In these areas the Sinhalese residents participated almost everyday. They also provided the satyagrahis with refreshments. They gave cash donations in their respective places to Messers N.R. Rajavarothayam, MP, and T. Sivasithamparam, MP. A model contribution may be indicated here. 7th March 1961 N.R. Rajavarothayam, Esq., Trincomalee. Sir, Please accept my humble contribution towards the struggle to achieve your aims. Sgd. K.W. David Silva (Trincomalee) N.B.: enclosed currency for Rs. 50/- When Mannar commenced its satyagraha under the leadership of Mr. V.A. Alagakone, MP, several Sinhalese lent their support to the satyagraha. One of the sympathizers of the movement and one who went to the Mannar kachcheri to see the satyagrahis and gave them his moral support was the Ven. Sir Jinaratne Thero, a Sinhalese Buddhist priest. In an appeal addressed to the Sinhalese people and the government, he said that it was inhuman to deny the fundamental rights to which every community was entitled. He pointed out that earlier the Tamil problem was solved satisfactory to the Tamil-speaking people, the better it was for the whole of Ceylon. Heart-rending Sights There were some heart-rending sights at the satyagraha. One Maniccam of Trincomalee chained both his hands and feet and rolled a distance of nearly five miles in the hot Sun to the Trincomalee kachcheri, to participate in the satyagraha. He was accompanied by a large number of people, some of whom sang bajanai, all along the roads. There was a lame man known to be from Ilavalai, who had a consuming desire to see the satyagraha at the Jaffna kachcheri and participate in it. He left his home at about 7 am in his wheel-chair with the lame man and the group of men who kept him company, trudged along the road and it took them five hours to cover the distance of ten miles to the kachcheri. All of them reached the kachcheri fully soaked in perspiration. The lame man was happy to see thousands of satyagrahis squatted at the entrances. A group of young men from Mullaitivu walked ninety eight miles to reach Mannar to participate in the satyagraha. They were determined to cover the entire distance on foot without stopping and without talking shelter anywhere. They reached Mannar in two days in an almost exhausted condition. On their way the people served them with soft drinks but they refused to take any food. The People’s Leader Being a movement by and far for the Tamil speaking people, the satyagraha, by its peaceful character and the good and just intentions of those who initiated it, attracted even non-Tamil speaking supporters and sympathizers. The name of Mr. Chelvanayakam became a by-word for the unity of all Tamil speaking people and for correct and able leadership. The satyagraha days, indisputably, spotlighted that leadership. Before the advent of Mr. Chelvanayakam to active politics, the Tamil speaking people were a scattered community satisfied with a meager existence and in a degree unimaginative of their political future. It was Mr. Chelvanayakam who brought them out of their past mire and led them to a fresh trend of thinking, action and unity giving them their form and strength. He is a man of vision and firm decision. He is simple, honest and tolerant. Mr. Chelvanayakam is an amiable personality respected even by his political adversaries. At meetings he speaks little, but speaks well and uses correct language. Word after word he would pause and in that pause could be felt the dead silence of a hundred thousand people hanging on his lips, so to say, to hear the next word he would utter. Outside meetings and in the streets, he would be mobbed by crowds and he greeted them all with a genial smile. He is the leader of nearly twenty five lakhs of Tamil speaking people. ***** Chapter 13: Government’s Anti-satyagraha Moves (pp.124-130)