Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

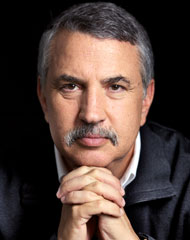

Tribes With Flagsby Thomas Friedman, The New York Times, March 22, 2011

David Kirkpatrick, the Cairo bureau chief for The Times, wrote an article from Libya on Monday that posed the key question, not only about Libya but about all the new revolutions brewing in the Arab world: “The question has hovered over the Libyan uprising from the moment the first tank commander defected to join his cousins protesting in the streets of Benghazi: Is the battle for Libya the clash of a brutal dictator against a democratic opposition, or is it fundamentally a tribal civil war?”

This is the question because there are two kinds of states in the Middle East: “real countries” with long histories in their territory and strong national identities (Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Iran); and those that might be called “tribes with flags,” or more artificial states with boundaries drawn in sharp straight lines by pens of colonial powers that have trapped inside their borders myriad tribes and sects who not only never volunteered to live together but have never fully melded into a unified family of citizens. They are Libya, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Bahrain, Yemen, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. The tribes and sects that make up these more artificial states have long been held together by the iron fist of colonial powers, kings or military dictators. They have no real “citizens” in the modern sense. Democratic rotations in power are impossible because each tribe lives by the motto “rule or die” — either my tribe or sect is in power or we’re dead. It is no accident that the Mideast democracy rebellions began in three of the real countries — Iran, Egypt and Tunisia — where the populations are modern, with big homogenous majorities that put nation before sect or tribe and have enough mutual trust to come together like a family: “everyone against dad.” But as these revolutions have spread to the more tribal/sectarian societies, it becomes difficult to discern where the quest for democracy stops and the desire that “my tribe take over from your tribe” begins. In Bahrain, a Sunni minority, 30 percent of the population, rules over a Shiite majority. There are many Bahraini Sunnis and Shiites — so-called sushis, fused by inter-marriage — who carry modern political identities and would accept a true democracy. But there are many other Bahrainis who see life there as a zero-sum sectarian war, including hard-liners in the ruling al-Khalifa family, who have no intention of risking the future of Bahraini Sunnis under majority-Shiite rule. That is why the guns came out there very early. It was rule or die. Iraq teaches what it takes to democratize a big tribalized Arab country once the iron-fisted leader is removed (in that case by us). It takes billions of dollars, 150,000 U.S. soldiers to referee, myriad casualties, a civil war where both sides have to test each other’s power and then a wrenching process, which we midwifed, of Iraqi sects and tribes writing their own constitution defining how to live together without an iron fist. Enabling Iraqis to write their own social contract is the most important thing America did. It was, in fact, the most important liberal experiment in modern Arab history because it showed that even tribes with flags can, possibly, transition through sectarianism into a modern democracy. But it is still just a hope. Iraqis still have not given us the definitive answer to their key question: Is Iraq the way Iraq is because Saddam was the way Saddam was or was Saddam the way Saddam was because Iraq is the way Iraq is: a tribalized society? All the other Arab states now hosting rebellions — Yemen, Syria, Bahrain and Libya — are Iraq-like civil-wars-in-waiting. Some may get lucky and their army may play the role of the guiding hand to democracy, but don’t bet on it. In other words, Libya is just the front-end of a series of moral and strategic dilemmas we are going to face as these Arab uprisings proceed through the tribes with flags. I want to cut President Obama some slack. This is complicated, and I respect the president’s desire to prevent a mass killing in Libya. But we need to be more cautious. What made the Egyptian democracy movement so powerful was that they owned it. The Egyptian youth suffered hundreds of casualties in their fight for freedom. And we should be doubly cautious of intervening in places that could fall apart in our hands, a là Iraq, especially when we do not know, a là Libya, who the opposition groups really are — democracy movements led by tribes or tribes exploiting the language of democracy? Finally, sadly, we can’t afford it. We have got to get to work on our own country. If the president is ready to take some big, hard, urgent, decisions, shouldn’t they be first about nation-building in America, not in Libya? Shouldn’t he first be forging a real energy policy that weakens all the Qaddafis and a budget policy that secures the American dream for another generation? Once those are in place, I will follow the president “from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli.” |

||

|

|||