It makes one laugh when political jokers like Anandasangaree and Siddharthan, shedding tears for the Tamils' plight, are pushed to the limelight to show some courage on behalf of Tamils for their convictions. Last year, spineless Anandasangaree ‘sobbed’ in front of the Lessons Learnt Reconciliation Commission (LLRC), “the people are not free now; the people want to be free; that is what they want first.” Siddharthan, similarly whined in front of the LLRC commissioners, “the majority community seem to believe they have conquered the Tamils and therefore their problems could be brushed aside.” These two jokers sided with the Sinhalese politicians for petty crumbs, when the LTTE was defending the Tamil pride. Now, they can’t even stand up courageously for the self-respect of Tamils.

Some ex-Tamil Tigers like Muralitharan and Kumaran Pathmanathan (KP) shared the reflected glory, when they were with the LTTE in the past. Now, they are on their own (Muralitharan since March 2004, and KP since August 2009) and they have become laughing-stocks among Tamils for their turn-coat behavior. These descendants of Judas will never be loved by the Tamils for whatever service they promise to deliver by licking the sandals of tyrant Rajapaksa.

|

Professor Margaret Trawick (b. 1948) |

“The author, Margaret Trawick is a professor and head the Department of Social Anthropology, Massey University, New Zealand. Why did she choose Tamil Nadu to carry out her anthropological research? In the introduction to the book, she states, ‘Through my mother, I am Irish. In many ways, South India is to North India as Ireland is to England. South India has been dominated politically and culturally by North India for many centuries. Tamils in particular, the most populous of South Indian ethnic groups, take pride in their identity and more than once in this century have attempted to establish a separate Tamil nation. Also like the Irish, Tamils believe in strong sentiment: rage, grief, compassion, affection, desire, laughter and ecstasy are openly and frequently displayed in the streets and courtyards of Tamil Nadu. And like the Irish, Tamils value the gift of the gab: fabulous conversationalists, story tellers, singers and poets abound among them.’ And very few among the Tails will disagree with these opinions of the author.

Margaret Trawick first visited India in 1975, when she was 26 to carry out her dissertation research on ‘concepts of the body in South India’. Her husband Keith and son Daniel (then a four month-old baby) accompanied her. She stayed for 18 months in Madras, came into contact with S.R. Themozhiyar, the principal protagonist of this book. Themozhiyar became the Tamil tutor to the author, from whom she learnt Tamil literature. In 1979, after receiving a grant to work on translating Saint Manickavasagar’s Tirukkovaiyar, the author invited Themozhiyar to the New York state to improve her Tamil skills further. In 1989, she returned to Tamil Nadu ‘to finish reading Tirukkovaiyar with Themozhiyar and do a general study of forms of ambiguity in Tamil.’ Her husband Keith did not accompany her this time. She and her son Daniel lived with the poor family of her Tamil tutor Themozhiyar. This book is an outcome of this cohabitation of Margaret Trawick and her son, with Themozhiyar’s extended family of 20 individuals, spanning three generations. She was identified by the members of Themozhiyar’s household as ‘Peggymma (Peggy-Mother), Peggy being the dimunitive of Margaret, the author’s first name.

The book consists of eight chapters under the headings: What led me to Them, Generations, The ideology of Love, Desire in Kinship, Siblings and Spouses, Older women and Younger men, Lives of Children, and Final Thoughts. I wish to highlight her views on themes, namely, the ideology of love and siblings. According to the author, for Tamils, anpu (as Tamils know ‘love’ in a broader sense) has the following nine properties.

Containment (adakkam): Open expression of love is to be restrained, even if it is mother love. Tamils also do not express love among opposite sexes openly.

Habit (pazhakkam): Attachment, or a sense of oneness with a person or thing or activity, grows slowly, by habituation.

Harshness and cruelty (kadumai and kodumai): Physical affection for children is expressed not through caresses but roughly, in the form of painful pinches, slaps and tweaks. The movie song, ‘Adikkira kai than anaikum; anaikkira kai than adikkum’ (Hitting hand will hold, and holding hand will hit) expresses this sentiment beautifully.

Dirtiness (azhukku): ‘Defiance of rules of purity conveyed a message of union and equality and was a way of teaching children and onlookers where love was’, tells the author. This is exemplified by mother’s care of baby’s bodily excretions and the host’s cleaning of guest’s plate of food.

Humility (panivu): Love is implicated in expressions of humility and patience (porumai), the strength to sustain and endure.

Poverty and simplicity (ezhumai and eLimai): Self renunciation of luxury (such as fancy clothes and jewellery) for the cause of a loved one, as expressed in sentiments like, ‘I don’t want new clothes…as long as you are sick.’

Servitude (adimai): Illustrated as the servant of God, who receivd the highest respect among the civilians. Elimination of the boastful ‘I’ (Naan) and substituting with the self deprecating ‘this slave’ (adiyean), exemplified by Tamil saints of the past.

Opposition and reversal (ethirthal and puratchi): Characterized by the use of the very intimate suffix ‘di’ (for girl) and da (for boy) among family members and close pals. When these intimate forms of address are used by acquaintances or strangers, they become derogatory.

Mingling and confusion (kalathal and mayakkam): Love erases distinction completely and mingle everyone, typified by the adage ‘We are all one’ (Onrae kulam Oruvane Thevan). In addition, love leads to dizziness, confusion, intoxication and delusion (mayakkam).

The author also observes, ‘Within the nuclear family, four relationships seemed to be be especially important to the Tamil people whom I knew. These were the mother-daughter, father-son, husband-wife and brother-sister relationships’. The love links between these four relationships are identified by the author as follows: ‘A man sees his son as a continuation of himself. A woman sees herself as continuation of her mother; the bond between brother and sister is strong but must be denied; the bond between husband and wife is conflictual but difficult to sever.’

As an example for the sentiments of sibling love among Tamils, the author has presented in the book, the following duet:

Brother: You were born to win many battles with your elephants and armies

You were born to marry your aunt’s daughter and live in joyful love!

Sister: Shall I tell you how my brother brought me up like a darling daughter.

Sheltered under his wing?

Shall I tell you of the unimaginable misfortune which separated us?

Brother: We were born together, joined like the eye and the pupil and the image within!

Though the earth and sea and sky should come to an end,

We shall not forget our love, Nothing can break our bond!

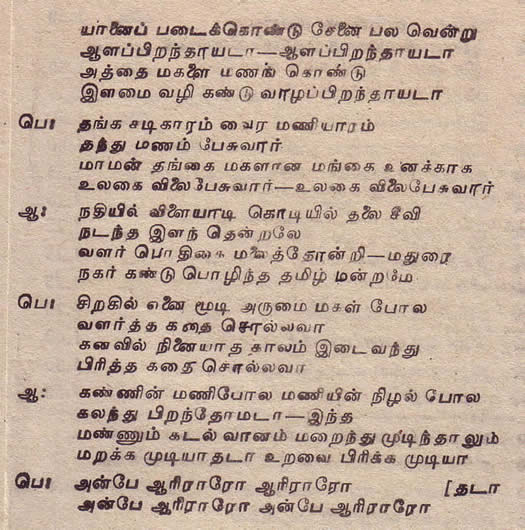

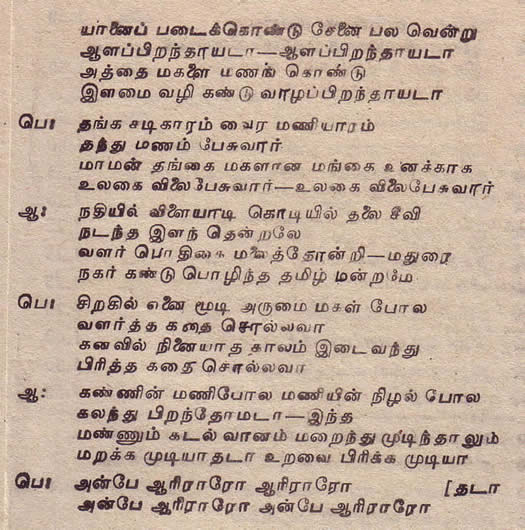

This duet is none other than an English translation of that touching lullaby ‘Malarnthum Malaratha Pathi Malar pola’ penned by poet Kannadasan (whose name is not mentioned in the book!) for the hit movie Pasa Malar. The book author has stated that this particular movie, although released in the early 1960s, still enjoy  mass appeal among the Tamils, for extolling the sentiments of sibling love. Of course, this lullaby duet of Kannadasan should be enjoyed in the original (not presented in the book!) since translation does not do merit to the beauty and cadence of the poet’s choice of Tamil words in expressing sibling love. Kannadasan also made an elegant use of the very intimate suffix (da for boy) to express intimacy and love, in this lullaby. In original (undoubtedly, a vintage Kannadasan), the cited duet reads as presented adjacently.

mass appeal among the Tamils, for extolling the sentiments of sibling love. Of course, this lullaby duet of Kannadasan should be enjoyed in the original (not presented in the book!) since translation does not do merit to the beauty and cadence of the poet’s choice of Tamil words in expressing sibling love. Kannadasan also made an elegant use of the very intimate suffix (da for boy) to express intimacy and love, in this lullaby. In original (undoubtedly, a vintage Kannadasan), the cited duet reads as presented adjacently.

Well, how can I sum up my thoughts on this book? The author states in one page, ‘The assertions I make about Tamil love would be considered by most Tamils to be banalities – too obvious to be worth writing a book about’. I, for one, disagree with this modest sentiment of the author. I believe Maragret Trawick had written a worthy book on a worthy topic about Tamils.”

Home

Home Archives

Archives Currently, quite a few among the Tamils (in Eelam and Tamil Nadu) pride themselves as leaders. Among the living, R. Sampanthan, Douglas Devananda, V. Anandasangaree, V. Muralitharan (aka Karuna), D. Siddharthan, and S.C. Chandrahasan posture as ‘political’ leaders. The last two have some name recognition as the sons of revered Federal Party leaders. They all share one commonality. With the marginal exception of Sampanthan (who for some years was on V. Prabhakaran’s side), the rest openly expressed anti-Prabhakaran sentiments to curry petty favors with the Sinhalese. How many among these can boast that they are loved equally by the Tamils as Prabhakaran and his band of heroic Tamil Tigers were admired for the pride they delivered?

Currently, quite a few among the Tamils (in Eelam and Tamil Nadu) pride themselves as leaders. Among the living, R. Sampanthan, Douglas Devananda, V. Anandasangaree, V. Muralitharan (aka Karuna), D. Siddharthan, and S.C. Chandrahasan posture as ‘political’ leaders. The last two have some name recognition as the sons of revered Federal Party leaders. They all share one commonality. With the marginal exception of Sampanthan (who for some years was on V. Prabhakaran’s side), the rest openly expressed anti-Prabhakaran sentiments to curry petty favors with the Sinhalese. How many among these can boast that they are loved equally by the Tamils as Prabhakaran and his band of heroic Tamil Tigers were admired for the pride they delivered?

mass appeal among the Tamils, for extolling the sentiments of sibling love. Of course, this lullaby duet of Kannadasan should be enjoyed in the original (not presented in the book!) since translation does not do merit to the beauty and cadence of the poet’s choice of Tamil words in expressing sibling love. Kannadasan also made an elegant use of the very intimate suffix (da for boy) to express intimacy and love, in this lullaby. In original (undoubtedly, a vintage Kannadasan), the cited duet reads as presented adjacently.

mass appeal among the Tamils, for extolling the sentiments of sibling love. Of course, this lullaby duet of Kannadasan should be enjoyed in the original (not presented in the book!) since translation does not do merit to the beauty and cadence of the poet’s choice of Tamil words in expressing sibling love. Kannadasan also made an elegant use of the very intimate suffix (da for boy) to express intimacy and love, in this lullaby. In original (undoubtedly, a vintage Kannadasan), the cited duet reads as presented adjacently.