Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi RevisitedSivarasan Cover-Upby Sachi Sri Kantha, May 10, 2011

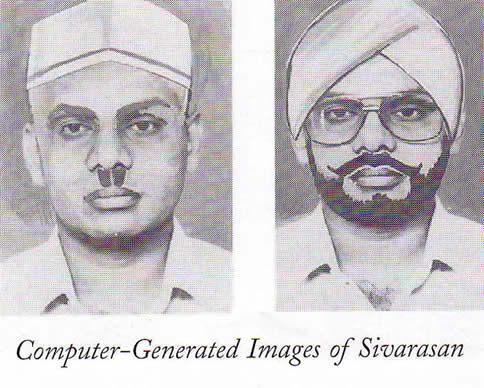

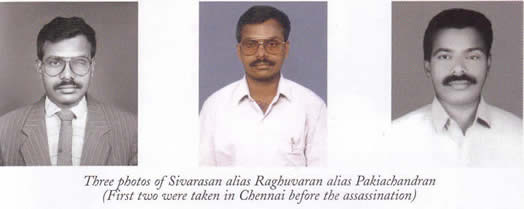

Consider this equivalent. In President Kennedy assassination on November 22, 1963, the assassin was Lee Harvey Oswald, who himself was assassinated by Jack Ruby, two days later on November 24, 1963. In Rajiv Gandhi's assassination that happened on May 21, 1991, the assassin was ‘Dhanu’ (who instantly died during the assassination), who was handled by Sivarasan. As the links of Jack Ruby to various sinister characters have been traced by many Americans, Sivarasan’s links to similar sinister characters have only been partially hinted, but still remain hidden. I provide the pro and con views relating to the LTTE’s involvement in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination. The 'Pro' view as it appeared in the India Today magazine, before Sivarasan’s death, was authored by Anirudhya Mitra; but, one can easily assume that it received the full endorsement of the Special Investigation Team (SIT), then headed by D.R. Kartigeyan. What I find intriguing is that the article mentions that, “Shivarasan then selected his human bombs – Dhanu alias Gayatri and Shubha alias Shalini, two women members of the LTTE’s shadow squad. Incidentally, both the girls happened to be his cousins.” This contradicts with the ‘confessions’ extricated by the SIT team from other accused that when it came to decision-making on who should be the assassin (in other occasions), Prabhakaran made the final decision. If Sivarasan was in charge of selecting the human bombs for the Rajiv Gandhi assassination, the responsibility of Prabhakaran for this job was marginal at best. Also, make a note that according to this account, three times Sivarasan had crossed the Palk Strait cavalierly, before the assassination. He left for Madras from Jaffna in the first week of March 1991. Then, returned to Jaffna. Then, within a week, returned again to Madras on May 2, 1991 with Dhanu (the assassin) and Subha (substitute assassin), according to D.R. Kartikeyan and Radhavinod Raju. If this was the pattern, how come he opted not to return to Jaffna immediately after the assassination, during the 8 days of ‘window period’, before his photo was splashed in the Indian print media? Kartigeyan and Raju, in their 2004 book on the Rajiv Gandhi assassination, state that “On May 29, Sivarasan’s photograph was published for the first time in the media.” (page 67). After all, Sivarasan had successfully completed the ‘mission’ for which he was chosen. That he was hopping around for three months (June, July and August 1991) in South India, before being cornered in Bangalore, tells us that his non-LTTE sponsors wanted him to be in India! The 'Con' view presented by Dr. Norman Baker, which appeared in the Illustrated Weekly of India one year after Sivarasan’s death, offered some serious questions relating to the activity and movements of Sivarasan. To supplement these portrayals of Sivarasan, I also include two interesting features, in which the ‘know-all Tamil journalist’ D.B.S.Jeyaraj played a lead role. The first item, provides background information on Sivarasan written after his death by D.B.S.Jeyaraj in 1991. This item first appeared in the Frontline (Madras) magazine, and was republished in the Lanka Guardian (Colombo) in Sept.15, 1991. To the best of my knowledge, this remains as the one of the good published treatments about Sivarasan’s career upto May 1991. Before reading this item, please read my comment relating to Jeyaraj’s description of the caste group to which Sivarasan belonged. However, I’m unable to confirm the veracity of some of the details presented by Jeyaraj, relating to when Sivarasan joined the LTTE, and the reasons why the LTTE accommodated him, how he “became a senior member of the LTTE” and got “promoted” as the “acting Vadamarachchi commander”. The second item also was linked to the first item penned by D.B.S.Jeyaraj in 1991. This unsigned item appeared in the Tamil Times of April 1999, just before the Supreme Court verdict on the appeal of the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case was delivered. It cryptically mentions that the 1991 item by Jeyaraj “had been written on the request of Sivarasan’s relatives in Canada who wanted something written about him in the papers so that he would not be ‘forgotten’. Much of the information was supplied by them. The articles had nothing whatsoever about Sivarasan’s involvement in Rajiv’s killing and in any case was published only after his death.”

THE PRO-VIEW: Rajiv Assassination: The Inside Story by Anirudhya Mitra [source: India Today, July 15, 1991, pp. 22-29]