Ilankai Tamil Sangam

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Published by Sangam.org

by Lewis M. Simons, National Geographic, January 2006, pp. 28-35

|

"Only human beings can move me to despair," he said. "But only human beings can remove me from despair." |

A Critical Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

The National Geographic magazine published an 8-page article in its January 2006 issue on Genocide. It was authored by Lewis M. Simons. The ‘usual suspects’ were tagged in the first paragraph. “In mid-century the Nazis liquidated six million Jews, three million Soviet POWs, two million Poles, and 400,000 other ‘undesirables.’ Mao Zedong killed 30 million Chinese, and the Soviet government murdered 20 million of its own people. In the 1970s the communist Khmer Rouge killed 1.7 million of their fellow Cambodians. In the 1980s and early ‘90s Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party killed 100,000 Kurds…”

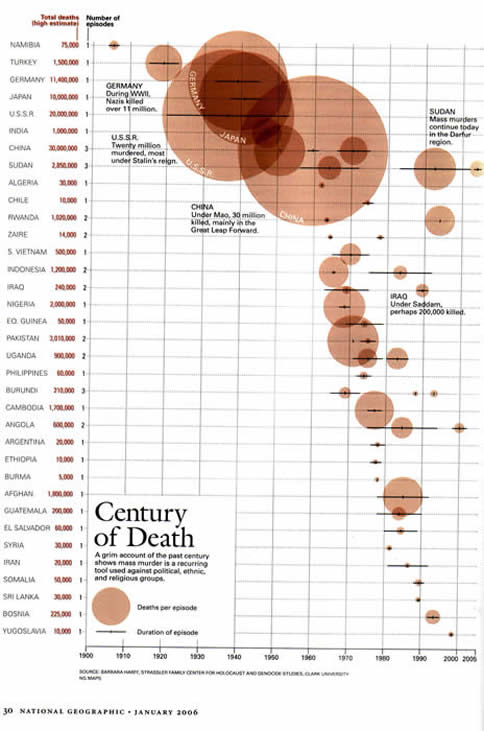

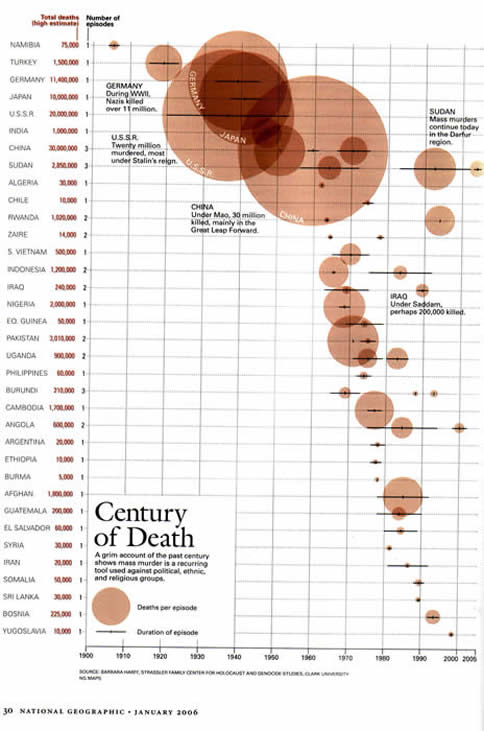

As ‘Defeating terrorism-Sri Lankan experience’, a special three-day seminar (May 31 and June 1 and 2nd), is being conducted in Colombo, I presume that delegates from the ‘usual suspects’ such as the Russians, Chinese and Cambodians will share notes among themselves about their experiences in how to conduct genocide under the garb of ‘terrorism eradication’ without creating too much ruckus. As for the Genocide of ethnic Tamils conducted by the Sri Lankan state (which has a 55 year history, beginning from 1956), the details provided by Lewis Simons in January 2006, leaves much to be desired. Nothing was mentioned in the text, which I reproduce below in entirety. The article also provides a comparative genocide scale map, which also I reproduce here. Sri Lanka appears as a data point (third entry, counting from the bottom). The ‘high estimate total deaths’ amount to only 30,000, and the period of occurrence was noted as “1989-90”. The data source cited is, “Barbara Harff, Strassler Family Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Clark University”. I presume that the ‘1989-90’ period refers to the 2nd JVP insurrection. It is acceptable that data collection errors do occur in the field. But, it is also unbelievable that a National Geographic article (known for its reliability!) should carry such a blatantly distorted number relating to genocide deaths in Sri Lanka.

The details I gathered from the website of Lewis M. Simons (www.lewismsimons.com) state that he had reported from Vietnam and throughout Southeast Asia, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, China, Japan, North and South Korea, and the former Soviet Union. He had received the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for exposing the Marcos family's hidden billions. I guess, he had never visited Sri Lanka. If so, he would have included it in his promotional website. But, I hesitate to place the blame entirely on the National Geographic or Lewis M. Simons. I’d assert that those Tamils living in the diaspora (especially in the USA and Canada) have failed in their duty to correct the National Geographic’s data source banks such as that of Barabara Harff of Clark University.

Article Proper that appeared in the National Geographic of January 2006

More than 50 million people were systematically murdered in the past 100 years—the century of mass murder: From 1915 to 1923 Ottoman Turks slaughtered up to 1.5 million Armenians. In mid-century the Nazis liquidated six million Jews, three million Soviet POWs, two million Poles, and 400,000 other "undesirables." Mao Zedong killed 30 million Chinese, and the Soviet government murdered 20 million of its own people. In the 1970s the communist Khmer Rouge killed 1.7 million of their fellow Cambodians. In the 1980s and early '90s Saddam Hussein's Baath Party killed 100,000 Kurds. Rwanda's Hutu-led military wiped out 800,000 members of the Tutsi minority in the 1990s. Now there is genocide in Sudan's Darfur region.

In sheer numbers, these and other killings make the 20th century the bloodiest period in human history. In 1944 Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish scholar who lost almost all of his family in the Nazi Holocaust, coined the word "genocide," from genos, Greek for tribe or family, and -cide, from the Latin for kill. Four years later, after the Nuremberg trials, the crime of genocide was recognized by the United Nations as the deliberate destruction of a racial, religious, or ethnic group. Today most societies add mass political killings to that definition.

Paul Rubenstein lost much of his family in the Holocaust. "Afterwards people said, 'Never again,'" he told me quietly as we drove through a U.S. military base near Baghdad. "Now I'm helping to develop the science to continue studying this kind of thing." He paused. "It's hard to imagine that I'm in the vanguard of the science of mass murders and mass burials. This wasn't supposed to happen today."

Paul Rubenstein lost much of his family in the Holocaust. "Afterwards people said, 'Never again,'" he told me quietly as we drove through a U.S. military base near Baghdad. "Now I'm helping to develop the science to continue studying this kind of thing." He paused. "It's hard to imagine that I'm in the vanguard of the science of mass murders and mass burials. This wasn't supposed to happen today."

Rubenstein is an anthropologist and a civilian employee of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He's also the deputy director of the forensics lab at Camp Slayer near Baghdad. For two years, even as Iraq's insurgency has grown deadlier, Rubenstein and a small team of scientists, most from the U.S. but also a few from other coalition countries, have been exhuming remains from mass graves. Using forensic techniques—linking bones, clothing remnants, identity cards, jewelry, photographs with names on captured government death warrants—they're coaxing secrets out of the death pits to determine who the victims were, where they came from, who killed them, and how, when, and why. Since 2004, U.S. officials say, hundreds of skeletons have been exhumed and turned over to the forensics team.

Although that number is tiny compared with the total number of Iraqis murdered, the effort is an impressive marshaling of the forces of science, all aimed at building airtight legal cases.

The forensic work at Camp Slayer is sponsored and choreographed by the U.S. Department of Justice, whose vested interest in proving Saddam Hussein a mass murderer has evolved as the Bush Administration's stated reasons for invading Iraq (weapons of mass destruction, links to 9/11) have proved false. Still, even as the death count mounts by the day—an esti-mated 26,000 Iraqis and 2,000 Americans and allies killed by late 2005—the investigation could bring value that surpasses the warfare and politics of the moment. If the forensics specialists demonstrate that Saddam Hussein and other mass murderers can be successfully brought to justice, they may help build a potent preventive against genocides of the future. This, at least, is the idealistic hope.

|

Lewis M. Simons, Pulitzer-prize winner in 1986 for international reporting |

The forensics facility occupies part of the grounds of a former palace compound of Saddam Hussein's, a onetime pleasure court with swimming pools and boating ponds that now bristles with antennas and satellite dishes servicing CIA, FBI, and U.S. military intelligence operations. Rubenstein walked me through a quaintly incongruous white picket fence to a cluster of well-lit, air-conditioned tents, where I met specialists examining, x-raying, and photographing skeletons and studying clothing and artifacts such as jewelry, wallets, and government identity cards. Patterns of neat bullet holes peppered skulls and garments, many of them the baggy trousers peculiar to Kurdish men. Staring at cardboard boxes filled with skulls in plastic bags and skeletons precisely arrayed on steel gurneys, inhaling the oddly metallic death smells, I flashed on America's current fascination with TV forensics programs like CSI and Crossing Jordan. The real thing is not entertaining.

Rubenstein was for the most part all business. I reasoned that this was his way of protecting himself, not just from an inquisitive journalist but also from the nightmare he lived each day. Once, though, he let down his guard. "As you work with the victims, especially the children—their clothing, the baby bottles, the little shoes, just like the ones we bought for our daughters years ago, the little hands, so expressive in death —you have to try not to get into the heads of the monsters who did this, or it becomes overwhelming. You look at a perfectly knitted baby bonnet with two bullet holes in it, and you think, These could be your own kids."

The killers sometimes treated men, women, and children differently. "The men show signs of torture, of being tied and handcuffed," Rubenstein said. "The women often had children with them and received, perhaps, the blessing of being shot once at close range. All of this is based on clear evidence, not speculation."

An early step in the forensic analysis is to remove clothing and personal possessions from skeletons before the specialists start examining the remains. This, explained Joan Bytheway, a forensic anthropologist from the University of Pittsburgh, is to ensure that experts don't form biases about the victims. Bytheway pointed out an entry hole at the top of a skull that she cradled, an exit hole near the left eye socket, and a radiating crack in the left cheek. Only after she and the other anthropologists incorporate findings like this into biographical profiles—"female, mid-30s, five foot four to five foot six"—do they reunite bones and possessions.

A few feet away from where Bytheway was working, Tim Anson, an Australian anthropologist from the University of Adelaide, showed me a partial skeleton on a gurney. It had been recovered from a grave near Al Hadr, about 55 miles southwest of Mosul. The most obvious thing about it was that only the back of the skull remained. "The entire face was blown away," said Anson. He also noted leathery, mummified tissue in the forearms and explained that this was because the person had been buried in the middle layer of a grave 12 to 14 feet deep. Even after as long as 20 years in the earth, bodies farther underground often contain fat and other soft tissue, while those closer to the top are reduced to bare bones.

In an adjacent tent radiographer Jim Kister demonstrated his work with a Faxitron, used to x-ray bones to identify the source of trauma. He clamped a large transparency of a man's rib cage to a light box and pointed to a bullet. "This guy took 11 bullets," he said. "He was shot to hell." Kister said he anticipated that defendants in the Baghdad trials would try to claim that shattered bones were postmortem and therefore inadmissable evidence. "These pictures tell a different story."

So far the forensics team has only identified about 15 percent of the skeletons examined. The results will be collected in a massive report by the Army Corps of Engineers. It won't be made public for many years, not until after the trials—decades after Iraq's mass killings began in 1987. The eight-year war with neighboring Iran was ratcheting down, and Saddam Hussein had ordered his bedraggled army to punish the minority Kurdish community, many of whom had supported Iran. Saddam Hussein used this involvement as an excuse to attempt to eradicate the Kurdish population, which had long been a thorn in his side. (See "The Kurds in Control," page 2.) By the time the campaign ended more than a year later, an estimated 100,000 Kurds were dead (though some Iraqi interest groups put the number as high as 182,000), including thousands poisoned by chemical weapons. Most were buried in secret mass graves.

Although reports of the killings became public almost immediately, President Ronald Reagan's administration and the State Department chose to ignore them. Because the administration had actively backed Iraq against Iran, the U.S. government was determined not to offend Saddam Hussein. He may have been a mass murderer, but at least he was, to paraphrase President Lyndon Johnson's reference to a South Vietnamese ally, our murderer.

Rubenstein acknowledged that with his mission narrowly focused on supplying evidence for the trials, recovering thousands of corpses from mass graves and returning them to families was not the administration's first priority (though some of the team may remain behind to help). "That will have to be left to the Iraqis," he said. "We're part of the litigation process. We're here to provide the same level of evidence that would be used in courts in the United States."

On the south coast of England, a world away from Iraq but joined to it by death, I visited Margaret Cox on the leafy, modern campus of Bournemouth University. Cox, an anthropologist and archaeologist, operates the International Forensics Centre of Excellence for the Investigation of Genocide (INFORCE). In 2004 Cox and her colleagues trained 33 Iraqis in the science of exhuming mass graves and identifying remains. (Under Saddam Hussein's government, Iraq had only a handful of forensic scientists to serve a population of 26 million.) After a five-month course that included exhuming a mock mass grave seeded with plastic skeletons, the group returned to Iraq where they began working on real graves and passing on their new knowledge to other Iraqis. During my visit, 12 of the most promising trainees were back in Bournemouth, polishing their skills.

Cox holds out hope that the investigative science she's teaching here, and that forensic scientists are developing in the field, carries promise for the new century. "If collected properly, forensic evidence speaks for itself," she said. "And the realization that forensics can expose the perpetrators may be sufficient to stop a genocide before it happens." That remains to be seen, but if it ever happens, it will be a powerful example of science functioning in the interest of humanity.

A few miles across town from the campus is a nondescript strip of brown unmarked warehouses and storage spaces. There, in a brightly lit, white-walled room set up like a small morgue, Cox introduced me to one of the Iraqis who'd volunteered to give up their varied careers in Baghdad and come to Britain to learn this grisly science. The individual I spoke with, whom I'll call X, was extremely enthusiastic and hopeful about the central role group members would play in helping millions of Iraqis finally determine the fate of family members and achieve at least a small measure of psychological peace.

Initially, X gladly agreed to be identified in this story. But shortly before it went to press he got word to me of death threats against him and his family and that because of these threats he was delaying his return home. Based on what I'd learned from investigators while I was in Iraq, the threats most likely were made by Sunni supporters of Saddam Hussein, who are striving to diminish evidence against the former dictator.

While I was visiting the little morgue, the Iraqis were working alongside British instructors, sifting soil for bone fragments and studying x-rays for gunshot evidence. X told me what he believed lay ahead when he returned home and how he planned to shift the focus of the task the Americans were carrying out. "Civil society is a new concept in Iraq," he said. "For us, the suf-fering of the dead is not over. The dead have rights, yes; they must have justice, yes; but the American approach, gathering evidence for the trial, is just the beginning. What we're doing is for the living."

No one can seriously question X's will and the nobility of his goals. But with the Bush Administration likely intending to pull out U.S. experts after the trials in Baghdad, coupled with the threats against X's life, the odds of X and his small number of Iraqi colleagues finding 100,000 or more murder victims and providing comfort to their families in the midst of seemingly endless warfare must be considered poor at best.

The Americans, with all their funds, expertise, equipment, and security, have set themselves a very limited goal. In Iraq, I'd flown in a U.S. Army Blackhawk helicopter to a gravesite in the Muthanna desert, near the border of Saudi Arabia, about 200 miles south of Baghdad. Because of their extreme sensitivity about protecting information related to Saddam's trial, the U.S. officials accompanying me would be no more specific about the location. As the Blackhawk made a tight circle, I looked out over a pale brown ocean of sand disturbed only by a misshapen doughnut of military tents, vehicles, and trailers. Called Camp Yankee, it was protected by concentric rings of private security contractors, courteous young men in mirrored glasses and military-style haircuts, carrying automatic weapons.

Off to one side a dark canopy shaded a fresh cut in the talcum-soft sand. The previous day American excavators had uncovered a tangle of skeletons about a shin's length beneath the surface. I could discern about 35 individuals, knee joints bent the wrong way, arms flung crazily over and under neighboring skeletons. Other layers were hidden beneath them.

The dry climate made for extraordinary preservation—complete skeletons, most dressed in the brilliant blues, reds, yellows, and oranges Kurdish women love. Some of the skulls were still draped with long hair. One contained a full set of pink and white dentures clamped in a mad grin. Another, near the center of the jumble, was hung with a waist-length beadwork necklace, eye sockets staring back at me, jaws stretched past the breaking point. Among the bones were scattered some of the simple things of daily life: white plastic yogurt tubs used to carry purchases home from the market, string bags of children's garments, earrings, government identity cards, plastic watches, baby shoes and bonnets.

Michael "Sonny" Trimble of the Army Corps of Engineers is in charge of the forensics team. Back home, he is curator of the famed Kennewick Man, the 9,200-year-old skeleton found in 1996 on the bank of the Columbia River, near Kennewick, Washington. Trimble is well-known in his field, having overseen the exhumation of bodies in Southeast Asia and Bosnia.

"These people were killed here 15 to 17 years ago," he said. "The graves were dug with a single pass of a front loader blade—each one around 10 or 11 feet wide and 35 feet long—the same way their army dug tank berms. There are 10 to 13 graves at this site. About 1,500 bodies—Kurds, judging by their dress. They were sprayed with AK-47s. We found the shell casings along the edges of the pits. The killing process was methodical."

When Trimble and the other American experts leave the country, Iraqis will inherit a massive problem: How to bring about national reconciliation and settle decades of ethnic hatred. Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi author and professor of Middle Eastern studies at Brandeis University, is taking the first step. He heads a foundation that has amassed millions of government documents related to mass murders. Many were recovered from secret police headquarters in the days immediately after the fall of Saddam. Some evidence was inadvertently destroyed when Iraqis used backhoes to dig into the graves in their rush to find the remains of missing loved ones.

"Evidence for the trials is just the smallest part of what must be done," said Makiya. "The main goal is to put on trial not just the 10 or 12 top individuals but an entire system of government. You must keep in mind that almost all Iraqis were caught up in the system, spying and reporting on each other. All of us—Kurds, Shia, Sunni—must come to terms with what I call the factional narratives that have replaced individual responsibility and acknowledge our own involvement. Otherwise we won't have healing."

With Iraq's future very much unknown as insurgency whipsaws the country, no one can seriously address these deeper issues of peace and reconciliation. So, whether Iraqis will face them, as South Africans did in the 1990s, remains an open question.

On my helicopter flight from Muthanna back to Baghdad, we carried 42 plastic footlockers, each containing a set of remains removed from the grave. We were delivering them to the team at Camp Slayer. I wrestled with a question: What is the human flaw that allows genocide to erupt again and again? More genocide has taken place within our lifetimes than at any other time. And much of it has happened while we in the so-called civilized world looked on or refused to look. Such was the case with Iraq.

To Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel, those who are indifferent are as guilty as the murderers. "The tragedy I know best, because I was personally involved in it, the Holocaust, made no distinction between the murderers and the bystanders," he told me. "How can you be a bystander? We Jews suffered not just from what was inflicted on us by the perpetrators but also by the indifference of our friends. If those of us in the camps had known at the time that our friends were not ignorant, but indifferent, we'd have gone beyond despair."

Yet Wiesel, who is probably the world's best known authority on the subject of man's inhumanity to man, says there is some reason to believe that the work being done with Iraq's mass graves victims could help ensure that the 21st century is less violent than the one before it. "The moment you give a face and a name, not just to the victim but to the killer, people respond with greater comprehension," he said. "It somehow puts limits on the phenomenon, which otherwise is incomprehensible because of the numbers and the magnitude."

Wiesel's ability to discuss life at its darkest with the apparent ease that most of us bring to everyday conversation can be daunting. But he was perhaps the most optimistic—at least the most hopeful—person I spoke to.

"Only human beings can move me to despair," he said. "But only human beings can remove me from despair."

*****

© 1996-2024 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.