Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Sri Lanka's WarTwo years onby Banyan, The Economist, London, May 19, 2011

MAY 19TH is the second anniversary of the Sri Lankan government’s announcement that its forces had killed Velupillai Prabhakaran, leader of the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. It marked the government’s definitive victory in a bloody 26-year civil war—one, moreover, that analysts, including this newspaper, had for years argued could never be won. Yet in the end victory was so complete that peace already seems permanent.

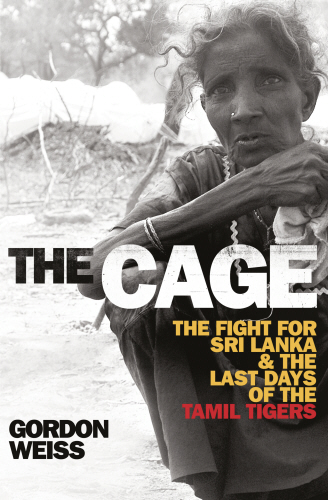

Despite all the horrors around the world since then, many will recall the sense of outraged helplessness felt internationally in the final months of the war. Their beleaguered forces, having in effect taken hundreds of thousands of civilians hostage in a dwindling patch of northern Sri Lanka (“the cage”), were pounded relentlessly. So were the civilians. The book’s outline of Sri Lankan history suggests that this brutality was not an aberration for the country. Not only had the war with the Tigers always been savage. So had been the violence of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, or JVP, a group espousing a strange hybrid ideology of Marxism and Sinhalese chauvinism, which staged two bloody uprisings in 1971 and from 1987-1989, both suppressed with enormous loss of life. The real value of “The Cage”, however, is its detailed account of the war’s denouement. It supplements and adds context to the findings of a report published in April by a panel of experts for the United Nations. Mr Weiss has done an excellent job of piecing together as accurate a picture as possible of what went on in the cage, which, at the time, the government sealed off almost entirely from outside observers. In the process, he recounts, as do the UN’s experts, compelling evidence of inexcusable disregard for human life on both sides of the conflict. If some of the massacres and murders described do not constitute war crimes, it is hard to know what would. Three factors helped the government get away with its ruthless approach. One was the sheer awfulness of the Tigers—as vicious and totalitarian a bunch of thugs as ever adopted terrorism as a national-liberation strategy. Whatever the government did, it could never be worse. It seems to have come close however, helped by the second factor: tight information management and censorship, including the intimidation of the local press, and a willingness to tell bald lies to foreign leaders. Third, unlike, say, Libya, it had the backing of both India and a veto-wielding member of the United Nations Security Council, China. It is not an encouraging precedent for a new multipolar world order. Sri Lanka’s government insists its forces pursued a policy of “zero civilian casualties”. It is now going on the propaganda offensive, organising an international counter-terrorism conference in Colombo at the end of this month, to advertise the success of its methods. The government will doubtless rubbish this book, and point to it, like the experts’ report, as evidence of the UN’s prejudices against it. In fact the book, which also tells stories of individual Sri Lankan soldiers’ heroic efforts to save civilian lives, is scrupulously fair. But it will make little difference to Mahinda Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s president, and his family, who, in the words of a Sri Lankan analyst quoted in the book, are “transforming Sri Lanka from a flawed democracy to a dynastic oligarchy”. That description is true enough. But a troubling aspect which the book rather skates over is that the Rajapaksa clan seems, among the Sinhalese majority, to enjoy genuine popular support. And foreign criticism, such as the UN experts’ report and this book, only enhances its popularity. That makes it still seem unlikely that there will be any true accountability for atrocities committed in Sri Lanka’s war. In that sense the book reads as a lament, not just for those slaughtered, but for what the author calls a “co-operative view of international relations”, which maintains that “the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians do count, and that the way you fight a war does matter, even when your cause is just.” *The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka & the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers. By Gordon Weiss. Bodley Head; 384 pages; £14.99 ------------------------------------- Gordon Weiss- On conflicts and counterpoints"Random Reads" by Random House India, in Authors, History, Opinion, Politics on May 4, 2011 at 4:18 pm One lovely day in India, as a young man, I was robbed of everything I then possessed. It was in the mid-1980s. I had just crossed the border by bus from Nepal, where I had been walking in the mountains. The authorities had opened the high passes too early and my hiking party had been caught in an avalanche. An unusually early spring sun had melted the snow and one young German had been killed by the tons of rock and ice that cascaded down like a hand sweeping salt from a table. A few days later I fell over a small cliff during a snowstorm and injured my leg. I left the Annapurna mountains, and made for the capital. In Kathmandu I collapsed in the street with dysentery. I slowly recovered in a small hotel room over many days and nights, drinking only ginger tea brought to me by the kind owners. They put me on a bus to Gorakhpur, driven by a Shrek-like creature who seemed possessed by the devil himself. I was scared but decided that if I were to die I would rather it be with an uninterrupted view, so I climbed out of the bus window and onto the roof. I dozed on a cushion of traders’ bundles in the warm sunshine, lurching from side to side with the peaks of the Himalayas poking the sky around me. On the train at Gorakhpur station, I loaded my luggage into a compartment, and turned my back briefly to look for a better place to stow my backpack. When I went to sit down, to my astonishment my pack, and the bag containing my passport, money, camera, and diary were all gone. It was as if they had never existed. None of the passengers appeared to have noticed. For a young traveller, it was the end of the road. I had saved for years to travel in India, a childhood dream that evaporated in a moment of misfortune. My first reaction was disbelief, followed quickly by distress, and then hot anger. I wanted to lay my hands on the thief. I searched around the compartment. As the train pulled out without me, I stalked up and down the platform. Futility, however, and my feverish condition quickly overcame me. I sat on a railway bench. The sun shone. The sounds of life all around filled the sweetly fetid air. There were friendly and inquisitive faces watching me with long stares. India lulled me to surrender, and I did. Cast so suddenly adrift, I was not only not alone, but a part of all. Without money, I wandered for days, begging for food and drink, and slept by a tea stall. I felt no shame, and nor did the people from whom I begged inflict shame upon me. What could a rock feel, or a leaf, a beggar, or a thief? I was no more, nor anything less than anything I could touch, breathe, see, or hear. I floated on the current I had encountered, until eventually I was washed onto a shore of sorts again. My dacoit had been my saviour. Without him or her, I might have climbed mountains, wandered through temples, and crossed deserts without ever seeing. I record this naïve encounter to which I still cling to in middle age as a counterpoint to the hard-edged subject of my book. The Cage is about many things, but it begins with the complex conflict between the minority Tamils and the majority Sinhalese of Sri Lanka. It uses their thirty-year civil war and the history of Sri Lanka as a cipher with which to examine national liberty, the global war on terror, Indian Ocean geopolitics, colonialism, and political hypocrisy. Mostly though, it is about the miniature tragic opera of Sri Lanka, ostensibly a land blessed more than most but heavily burdened by strains of the ugliness of humankind. To write about the conflict between two peoples, as an outsider, is to steal upon the space of a very private affair. It is, after all, a relationship carefully built over many years. Details are important to them, and they hoard them in a store. They have their familiar arguments, and even if discussing a piece of fruit, it quickly descends into who did what to who first. Everything is backed by evidence drawn from the store. Like an old married couple, they hate each other, but they hate even more those who judge their endless quarrel. They assert their right to fight in peace, without exposure. As individuals, they believe that only they suffer, and that nobody else could possibly comprehend their pain. They are as blind to their own faults as they are to the suffering of their adversary, and triumphant at each discovery of fault in the other. When they are violent, it is easily justified. During the eleven months it took me to research and write The Cage, I often felt like a dacoit, stealing onto territory that strictly speaking was not mine. I do not have a dog in the Sri Lankan fight, and hold to no particular prejudice. I wrote as only an outsider can, with commonplace observations that perhaps some Sri Lankans will feel misses the point. I have stolen their story, and have tried to hold it up to the light to expose it, much as the dacoit who stole my possessions inadvertently exposed me. They will critique details, scream that I am biased, and hate me for my interference. But I have written it largely for those who cannot, because they are dead, and for those of my friends who remain in Sri Lanka, and who hope and work for something different. After a few days I woke from my reverie. I learned that the torn ticket stub in my waistcoat was redeemable. The trance broken, I caught a long train to New Delhi. After a visit to my embassy, I settled down at the Sunny Guesthouse to wait two weeks for my new passport. I read Tagore, and reveled in his all-too-human exhortation to be mad and drunk and go to the dogs. Tagore was another dacoit, stealing beautifully onto forbidden territory to reveal ourselves to ourselves. He scoured even the most private spaces of our universality. Gordon Weiss was the United Nations Spokesman in Sri Lanka for two years during the recent civil war. For two decades, he worked as a journalist and for international organisations in numerous conflict and natural disaster zones. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the University of Sydney, Australia. The Cage will be published in May 2011. |

||

|

|||

A book, published this week, by

A book, published this week, by