Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home Home Archives Archives |

Gaza's Food Heritageby Laila El-Haddad & Maggie Schmitt, Aramco World Magazine, Nov/Dec 2011

"I always watched my mother cook," says Um Ramadan, as she peels purple garlic cloves by her kitchen window, which looks out on a Gaza City street teeming with early-evening activity. "But I didn't really learn to cook until I married and my mother-in-law taught me." Her husband's family, like her own, were fishing-people from the Palestinian port of Yaffa, exiled before either he or she was born. Yaffa—now part of the Tel Aviv—Yafo conurbation—is no longer what it was, but we can still taste it. From generation to generation, its sophisticated style of seafood cookery has been passed along, a thread of memory preserved in the deft gestures of hands, the precision of palate.

As home to the largest concentration of refugees within historic Palestine, Gaza is an extraordinary place to encounter culinary traditions, not only from hundreds of towns and villages that now exist only in memory—depopulated and destroyed during the Palestinian exodus of 1948—but also from the rest of Gaza's long history. Through decades of conflict, families in Gaza have held to recipes and foodways as sources of comfort, pleasure and pride. Unable to control much else in their lives, Gazans are renowned for lavishing care and attention on food and family. Visiting kitchens up and down the Gaza Strip, talking to women about cooking and about life, offers lessons in the vital art of getting by with grace. Indeed, it seems that, in Gaza, everyone is delighted to talk about food. Approached for an interview, most Gazans brace themselves to explain one more time—gently, patiently—the impossible political situation of the Strip. When they discover that the subject is not politics but peppers and lentils and the way grandmother made maqluba, there is a moment of astonished delight before they rip into the topic. Passers-by crowd around, each proffering a hometown recipe: "No, no—it's much better if you add the onions at the end!" We went to Gaza to seek these conversations, because cuisine always lies somewhere at the intersection of geography, history and economy. It is a cultural record of daily life for ordinary people. Where recipes come from and how people learn to cook them reveal much about family histories and places of origin. Where food comes from, what it costs and what can and cannot be obtained reveal much about Gaza's labyrinthine economy. And the recipes themselves are a glimpse into history. A sliver of green between the desert and the sea, Gaza and its environs have prospered since antiquity as a hub along essential transit routes—on the one hand, between the Levant and Egypt and, on the other, between Arabia and Europe. While it is part of the greater Mediterranean food-universe of olives, fish, rice, chickpeas and garden vegetables, it is also a bridge to the desert culinary worlds of Arabia, the Red Sea and the Nile Valley.

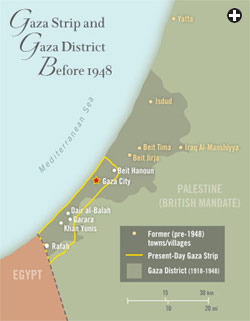

When we speak of modern Gaza, we are referring to the present-day Gaza Strip, which is some 40 kilometers (25 mi) long and four to eight kilometers (2-1/2 - 5 mi) wide, within the borders set in 1967. Historically, however, the greater Gaza District—one of the administrative districts of British Mandate Palestine and, before that, the Ottoman Empire—comprised a much larger region to the north and east. In culinary terms, the Gaza region was both a coastal one of seafood and an interior farming one, rich in vegetables and legumes. This division between coastal and interior cuisines persists today. The founding of Israel in 1948 divided the historic Gaza District and separated today's Gaza Strip from the rest of historic Palestine, and the 1967 Israeli occupation cut it off from both Egypt and the West Bank. This geopolitical fact, combined with the frequent closure of Gaza's borders over the past two decades, has resulted in isolation and uncertain political and economic circumstances, within which Gazans have had to adapt their cuisine as much as all the other aspects of their lives. "They make something like this in the rest of Palestine," cooks we interviewed would say, showing us a favorite dish, "but we add hot chiles and dill." Hot chile and dill: This is the quintessential modern Gazan spice combination. Whereas Lebanese cooks have no tolerance for spicy heat, and cooks from other parts of Palestine use it in moderation, Gazans take pride in making you sweat, whether using fresh green chile peppers crushed in a mortar with lemon and salt or else filfil mat'houn, ground red chile peppers preserved in oil and sold as a condiment and ingredient, resembling North Africa's popular harissa. The ubiquitous tabikh bamia, okra stew with oxtail, andmolukhiyya, mallow soup, are both served with green chile and dill seeds crushed with lemon, cutting their dark tastes with a blaze of brightness. Chiles are ground with meat to make kofta kebab and they are mashed, in the uniquely Gazan clay bowls called zibdiya, to make Gaza's signature tomato salad, dagga. Sun-dried, the same peppers are used in winter dishes such as maftul, the Palestinian version of couscous, in which the chile is called "the bride of the maftul" (arusit al-maftul) for the modest and delicate way it perfumes the grains as they steam.

After shopping with her at the Gaza fishing port, we learn a few other memorable uses of chile-and-dill from Um Ramadan. Gaza used to be famous for fish: Nine nautical miles off its shores, there is a deep channel used by great schools of fish as they migrate between the Nile Delta and the Aegean Sea. But the Israeli navy limits Gaza's fishing fleet to just three nautical miles from the coast. Though inland fish-farms attempt to compensate by producing tilapia, Gazans still prefer what they've been eating for centuries: red mullet and sea bream, sardines and sea bass, as well as an exuberant diversity of crabs, shrimp and other shellfish. Having carefully selected several medium-sized red mullet and some tiny shrimp, Um Ramadan leads us home. Her plan is to prepare a Yaffan recipe for spicy fried fish stuffed with dill, along withzibdiyit gambari, the typically Gazan dish of shrimp with tomatoes, spices and peppers stewed in a zibdiya, which functions as mortar, cooking pot and serving bowl in one. Soft-spoken, precise and unflappable, Um Ramadan effortlessly navigates her kitchen as she tells her family's history, interspersed with an encyclopedia of recipes. These recipes Um Ramadan shares belong to the grand repertoire of Gazan seafood cuisine, the culinary heritage of the coastal cities. Most are elaborate and urbane, requiring several stages of preparation. They also make much use of protein, a clear sign of the prosperity and sophistication of the community from which they emerged. Other dishes in this repertoire include caramelized rice with calamari rings; small squid stuffed with rice and spices; oven-roasted crabs stuffed with ground red chiles; stingray soup (a lemony delicacy beloved in Yaffa winters); andsayadiyya, "fishermen's delight," with layers of spiced rice, caramelized onions and marinated sea bass. In general, larger fish are often grilled and smaller fish are fried. Sardines—once wildly abundant during their migrations in spring and fall—are often baked on a tray with a spicy tomato sauce or ground to make fish kofta.Even in so small a territory as the Gaza Strip, food customs vary greatly from one region to another. Almost a world away from the urbane heritage of the coast, people with roots in southern Palestine's agrarian interior enjoy ingredients and tastes that are completely different—but no less charged with memory. Especially in the damp chill of Gaza's winters, rural people and their descendants crave the hearty, one-dish stews unique to Gaza, often made with original combinations of humble, inexpensive ingredients. These, too, are often regional: A native of southern Gaza is unlikely to know how to prepare sumagiyya, a slow-simmered stew of chard and meat flavored with red tahini and an infusion of sumac berries that is a traditional holiday dish in Gaza City.

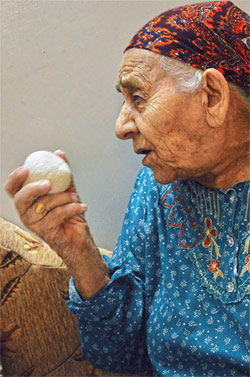

Other popular stews include fogaiyya, made with small chunks of beef or lamb, chard, rice and chickpeas and generously doused with lemon juice and fried garlic, and rumaniyya, a late-summer dish of eggplants and lentils cooked with sour pomegranate juice and thickened with tahini. Rural areas also make broad and original use of wild greens in dishes such as hamasees, in which sour greens are stewed with lentils, andkhobayza, which is mallow cooked with tiny dumplings. Rijla (or baqla)—purslane—is found all around the Mediterranean growing in the urban wild, through cracks in sidewalks and in abandoned lots. This small-leafed succulent is a favorite of peasants from the Gaza District, either raw or stewed with tomatoes and chickpeas. Um Ibrahim, 86, remembers eating rijla during the exodus of 1948: "We would find it growing between the bushes where we hid, and for a long while, it's all we survived on," she recalls. In her home in the Deir al-Balah refugee camp in the central Gaza Strip, she is one of the few who remember pre-1948 life—and as for many of her generation, it is for her often more vital than the present.

"I am telling you about how we would cook and eat in the past, but here everything is unwholesome. It is bad food. In the past, we ate very heartily and were very healthy." Her eyes gleam as she describes the wild greens and handsome squashes of Beit Tima, her home village, where her father had been mayor before they were driven out in 1948. It's clear from how she talks that, since that day, everything else has been a shadow, a long wait. If she is to talk about food, she will talk about food before the exile. Since then it has all been un-provided rations: flour, beans, sugar, salt, powdered milk. While Palestinians have adapted to this reality, creating innovative dishes with what ingredients are available, for Um Ibrahim, as for many elders, food—real food—is always in the past tense.

Many who have grown up in Gaza's refugee camps and towns, she explains, have never had full access to the foods of their parents and grandparents, because of the general unavailability or high prices of fruit, vegetables, dairy and meat. As a result, they don't know or don't appreciate some of the traditional preparations. For example, she says, her children don't like kishik. Says Um Ibrahim: "Ah! Kishik! It was one of our most favorite foods. It was cooked with chickpeas and meat. Beautiful!" Before refrigeration, throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, kishik was a way to conserve the nutritional value of dairy products by fermenting and drying a paste of milk and grain. In her native Beit Tima, Um Ibrahim learned to make kishik from wheat kernels, which she ground coarsely in a heavy mortar and left to ferment with yoghurt or buttermilk. She then would shape disks that were dried in the sun, which allowed their long-term storage. When winter came, the disks were reconstituted with water, blended until smooth, and then cooked with mutton, chickpeas and rice. Just south of Deir al-Balah in Garara, however, women prepare kishik today with plain flour, and they flavor it in characteristically Gazan style with crushed dill seeds and flakes of red chiles. When dried, this kishik is crumbled over skewered grilled tomatoes and dressed with mashed garlic and minced dill. A few kilometers still further south in Khan Yunis, kishik is ground to a powder and mixed with olive oil, lemon juice and crushed dill seeds, and the moist paste is eaten with flatbread or crumbled on top of salads.

Gaza's everyday inland foods tend to favor spicy-sour one-dish meals based on vegetables and legumes, but its celebratory festival foods are heavier on meat and richly spiced rice. There is history to this: Throughout Palestine, meat-based meals have historically been reserved for special occasions: holidays, family visits and important life events. Some of these dishes, such as fattah or mansaf, are based on the old peninsular Arab custom of dousing bread with broth and eating it with roasted meat. Other dishes trace their ancestry to the spiced rice dishes of the courts of Persia and Baghdad: notably qidra, spiced rice with meat and whole cloves of unpeeled garlic cooked slowly in a sealed clay pot, andmaqluba, in which meat and vegetables are layered with spiced rice, then turned upside-down before serving; the resulting vegetable-studded dome is adorned with almonds or pine nuts. These dishes, which require elaborate preparation and spices from all over the world, for centuries showcased both a host's generosity and a cook's acumen. In Gaza, there is a standard mixture of spices used for them, known simply as "qidra spices," that includes cinnamon, turmeric, nutmeg, dried lemon, ground red chiles and allspice. Cooks vary both the ingredients and the proportions, of course. As these are demanding recipes, many urban families today have them prepared by professionals, some to save time, others to save on cooking fuel. This is where Um Hamada and the women of the Zeitun Women's Cooperative step in. Tired of the helplessness many Gazan homemakers feel in an economic situation of nearly universal male under- and unemployment, caused by the closure of borders and subsequent collapse of industry in Gaza, Um Hamada and her neighbors in Gaza City's historic Zeitun neighborhood decided to put their cooking skills to work to support their families. They take orders for festive foods and—in a tiny but astonishingly efficient kitchen—prepare great vats of stuffed vegetables called mahshi, towering mounds of maqluba and all manner of pastries and sweets for all kinds of special events. All the women learned slightly different family versions of the dishes, so debates flourish in the kitchen, but without slowing the six or seven pairs of hands that deftly chop, slice, measure and stir in harmony.

Gazans from all backgrounds generally finish ordinary meals with sweet sage tea, followed by seasonal fruits and crisp summer vegetables like cucumbers and peeled carrots. Special occasions, however, call for dessert pastries. Of the many made in Gaza, none is as splendid—nor as uniquely Gazan—as knafa arabiya. While knafa is a broad category of dessert made throughout the region, knafa arabiya is the jewel of Gaza and only Gaza: a rich, buttery sheet of layered walnuts and toasted semolina breadcrumbs perfumed generously with cinnamon and nutmeg, soaked in warm syrup. Rougher and more rustic than other knafas, it is also richer, and its flavors run deeper—a metaphor perhaps for the women like Um Ramadan, Um Ibrahim and Um Hamada, whose daily creativity in the resilient kitchens of the Gaza Strip give Gazan cuisine its true heart.

450 grams (1 lb.) lean stewing beef or lamb, trimmed of fat, cut into Wash chard well, chop finely and set aside. Place meat and water in a stockpot and bring to a boil, skimming any froth. Lower heat to medium. Tie spices in a piece of gauze or disposable tea filter and add with onions. Cover and let simmer on medium-low heat for 1-1/2 to 2 hours, or until meat is tender. Stir in rice, 1-1/2 tsp. of the salt and canned chickpeas. (If using dried chickpeas, add them to the meat halfway through cooking.) Cook until rice is soft, approximately 10 minutes. Add chard by handfuls, stirring after each addition. Decrease heat to low. Meanwhile, in a zibdiyaor mortar and pestle, mash the garlic and remaining 1/2 tsp. salt. Fry the garlic in olive oil until lightly browned, 1-2 minutes. Add to stew and mix well. Just before serving, stir in lemon juice. Pour into bowls, garnish with thinly sliced lemon wedges, and serve with flatbread.

1/2 tsp. salt

In a Gazan clay bowl or zibdiya (though any mortar or curved-bottomed bowl will do), mash garlic and salt into a paste using a pestle. Add chiles and continue to crush. Add tomatoes and mash until the salad reaches a thick, salsa-like consistency. Mix in dill. Top generously with olive oil. Serve with flatbread on the side for dipping VARIATIONS:

Cook peeled shrimp in a dry pan for about three minutes, until the liquid they release has evaporated and shrimp are pink. Skim off any foam. Set shrimp aside. Coarsely chop the green pepper, and crush it with 1/2 tsp. of the salt. Chop dill and garlic finely and rub together by hand. In the same pan the shrimp were cooked in, sauté onions in olive oil. When onions are transparent, add tomato paste, and stir well. Mix in tomatoes, spices, crushed chiles, water and the dill and garlic mixture. Stir well. Simmer for 10 minutes on low heat, and then stir in shrimp. Meanwhile, toast the nuts and sesame seeds, or fry them until golden in 1 Tbs. olive oil and set aside. Pour the shrimp mixture from the pan into the zibdiya. (An ovenproof earthenware dish or individual ramekins will also do.) Cover with sesame seeds, nuts and parsley. Bake for 10 minutes covered with aluminum foil, then remove the foil and bake another few minutes until the top is crusty. Serve with bread.

1 kg. (35 oz.) soft wheat berries or fine bulgur With a mortar and pestle or a food processor, coarsely grind wheat kernels. Knead softened kernels with sour yoghurt or buttermilk. Leave to ferment for three days, preferably outdoors or by a window indoors, kneading the mixture daily. Once fermented, add salt, dill seeds and red pepper flakes, if desired. Divide into patties, dust with wheat bran or all-purpose flour, and then leave to sun-dry thoroughly on clean cheesecloth. 1 kg. (35 oz.) soft wheat berries, fine bulgur or all-purpose flour Grind and mix bulgur, buttermilk and spices as above. Mixture should be loose and liquid. Adjust buttermilk to achieve this consistency. Cover and leave to ferment in a large bowl for several days. When well fermented, divide into sealable storage bags and freeze. Defrost for use as needed.

Use the freshest spices available. Mix well and store in an air-tight container:

1/2 Tbs. ground nutmeg

Brown the meat or chicken in olive oil. Add water and bring to a boil, removing any froth. Reduce heat to medium and stir in all the items under "Flavoring for Broth." Simmer for an hour or so (more if using beef or lamb) until tender. Cool, drain, and reserve the broth and the meat separately. (While the broth is simmering, prepare the eggplant or cauliflower.) In a separate bowl, add salt, cinnamon and qidra spices to the rice and mix well. Set aside. Fry the onions and garlic in a separate pan in 2 Tbs. of the olive oil until caramelized. Remove from heat. In a large non-stick pot, add remaining olive oil and arrange potato slices in a circular, overlapping pattern, followed by tomato slices, sautéed onions and garlic, red pepper, carrots, reserved meat, roasted eggplant or cauliflower, and chickpeas. Add the rice mixed with spices on top of the arrangement in the pot. Ladle the broth over the rice until just covered, using approximately 2 cups of broth for every cup of rice. Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce heat to low and cover tightly for approximately 40 minutes or until rice is cooked. If necessary, ladle a little bit more of reserved broth, half a cup at a time, and leave to simmer until rice is cooked. Remove pot from heat and let rest, covered, for 30 minutes. Remove the lid and place a large round tray, serving side down, on the pot. Hold on carefully and flip the pot and tray upside-down. Gently lift off the pot, allowing the maqluba to slide out, as out of a mold. Adorn it with toasted pine nuts or almonds and parsley. Serve immediately with salad and yoghurt. Grilled eggplant or cauliflower for maqluba:

1/2 kg. (17 oz.) boneless mutton or beef, cut small Place meat and water in a pan and bring to a boil, skimming any foam. Reduce heat. Add chopped onion and whole-spice in bag. Cover partially and cook until tender. Meanwhile, mix kishik with its soaking water in a blender until smooth. Strain to remove any remaining lumps. Set aside. When meat is tender, strain and reserve the broth. Discard spices. Cook rice. When it is cooked, add broth, chickpeas, meat and the strained kishik. Bring to a boil, stirring continuously. Serve. Khan Yunis kishik: Grind soft kishik in a food processer or with a mortar and pestle, and mix with olive oil, lemon juice and 1 Tbs. crushed dill seeds to form a paste. Serve with flatbread. Garara kishik: Crumble kishik over oven-roasted or grilled tomatoes. Top with mashed garlic and chopped fresh dill.

The writers are coauthors of the forthcoming book The Gaza Kitchen, to be published in 2012 by Just World Books. This article appeared on pages 2-11 of the November/December 2011 print edition of Saudi Aramco World. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||