Ilankai Tamil Sangam30th Year on the Web Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA |

|||

Home Home Archives Archives |

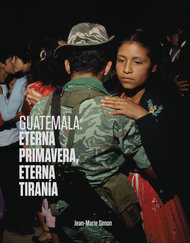

A Testament From Guatemala’s War Yearsby David Gonzalez, Lens, a New York Times photography blog, February 2, 2012

Efrain Rios Montt, a former Guatemalan general who is now bespectacled and gray-haired, now insists – through his lawyers – that he never issued orders that left thousands of his countrymen dead or disappeared in the 1980s. But Jean-Marie Simon remembers how on March 23, 1982 – the day he seized power in a coup – he looked every bit in control. Indeed, his rule would be marked by some of the worst atrocities that befell that Central American nation, where he now faces charges of genocide and war crimes. “I wish this trial would have happened 30 years ago, when he had a long life ahead of him in prison,” said Ms. Simon, who spent most of the 1980s photographing in Guatemala. “It is so disingenuous to say, ‘I didn’t know’ or ‘I wasn’t in control of the army.’ He was the commander in chief, he had command responsibility for the troops below him. Like a commander in the field once told us, there’s a very short leash between us and the National Palace.” This week, while Mr. Ríos Montt is under house arrest, Ms. Simon is reprinting her book “Guatemala: Eterna Primavera, Eterna Tirania,” a chronicle of the worst of the war years that builds upon her 1988 volume “Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny.” This time, she has raised $20,000 through Kickstarter to help produce 4,000 copies on glossy stock and with sewn bindings that will be sold for about $10 each. More important, she has set aside some 1,000 copies to be given away to schools and teachers in Guatemala. Guatemala endured a 36-year civil war that ended in 1996, but it still suffers from organized criminal violence and impunity. At a time when the country is confronting its past, Ms. Simon wants to make sure that young people there will be able to learn what their nation endured under military regimes. “I had been there in 2008 and was talking to people who said, ‘Oh, I have your book under my bed,’ ” she recalled. “Then I realized some people did not want to forget about the war. There was a new generation who wanted someone to tell them about it.” Few were telling Guatemala’s story when Ms. Simon first traveled to the country. She had been living in New York in the late 1970s, working as a waitress on the Upper West Side while pursuing her budding photography career. She had been offering to take pictures for nonprofits, and had mounted an exhibition of images of homeless women when she decided to go overseas. She said she approached Amnesty International about going to El Salvador, but it suggested that she travel to Guatemala, where violence against union members was increasing, as were abductions in the capital city. They wanted her to take pictures showing antennas and towers near the National Palace, to illustrate a coming report on the government’s role in the disappearances. When she got there in December of 1980, she arrived with an assignment from Geo magazine to photograph the ongoing conflict between the government and various guerrilla groups. But few people would talk to her, out of either fear or suspicion. Those emotions were not unfamiliar to her – she changed hotels every week. “I got worried I was going to go back with no pictures,” she recalled. “So I started taking pictures of daily life, and those are some of the pictures I like best. They depict this way of life that does not exist anymore.” Some of her contacts introduced her to others who helped her gain access to people caught up in the conflict. During this time, for example, workers at the Coca-Cola plant had been singled out for assassination. An official with their union gave her a written introduction to one of the guerrilla groups, the Guatemalan Workers Party, whose members took her out with them for a day. “You stand on the corner with a carnation, and a car comes by,” she recalled doing on that day. “Somebody asks,‘Do you have a copy of Time?’ You say, ‘No, I have a copy of Newsweek.’ Then you get in a car with black windows; then you get in a another car, blindfolded, and spend 45 minutes on a bumpy road. They took me to this room, they take off my blindfold. There are seven guys with hoods and big machine guns and a huge Claymore mine on the table.” Their first question? “Do you want a Coke?” Geo never ran her pictures – the story was spiked when Architectural Digest acquired the magazine. But Ms. Simon returned to Guatemala and was there when General Ríos Montt rose to power. Her luck at being one of the few international photographers at his palace press conference gave her the resources and recognition to continue documenting the country. “That coup saved my life photographically,” she said. “I had the money to stay put, and it became one of the most productive periods for me.”

On one trip, she joined with Allan Nairn and a documentary crew as they traveled to Nebaj and interviewed commanders and troops. In a nearby town, soldiers – who thought they had the blessing of their commander – described how they tortured prisoners. In other places, she and the film crew saw how the military was forcibly moving indigenous people into “model villages” while pressing the men into civil patrols. “What we saw was the intense beginning of this resettlement, where they razed villages and rebuilt them in uniform, symmetrical huts,” she said. “And the civil patrols? That was Ríos Montt’s big thing. It’s the most lasting thing a president of the 20th century gave Guatemala, because the effects are still being felt today.” In later years, she prepared reports for international human rights groups and connected visitors with local advocates who were demanding answers from the military regime. It was a sinister time, when activists would be murdered alongside their infant children. She recalls meeting one woman who told her that she had been raped by soldiers every night for a month – sometimes in front of her father. When the commander decided that she was not a guerrilla, he gave her a bar of soap, five pounds of beans and advice to start a new life. By the time her book was first published, she had decided to go to law school. She practiced for 10 years, then switched to teaching high school Spanish. Now living in Washington, she has returned often to Guatemala in recent years. Her book’s new edition has reconnected her with friends and colleagues, who helped her choose images for it (a chance reunion with a former picture editor led her to dozens of new images that she had not seen in decades). She speaks warmly about how she was able to produce it in Guatemala, with a level of quality that is equal to that found anywhere else. It is a point of pride born from a deep respect for those she saw take the greatest risks. Years ago, she used to visit Nebaj, where a group of nuns lived next door to soldiers (who had also set up a machine gun nest in the church bell tower). Separated from the soldiers by a wall, the nuns could hear the screams of suspected guerrillas being tortured. “The nuns turned on a tape recorder and you could hear people screaming,” she recalled. “Then they took us to the market. They were setting up an orphanage for children who lost their parents in the war. They went to the market to buy plastic bowls. They bought every color except one.” She asked them why. “We’ll buy any color except green,” a nun told her. “It’s our little protest against the army.” She laughed at the thought. “Everything is in the details,” Ms. Simon said. “That always stuck with me. It’s so easy to lose sight of who the heroes were in these circumstances. It was the locals who had everything to lose and nothing to gain.”

Jean-Marie Simon Dawn in the Ixil Indian town of Nebaj during the army occupation. 1984.

|

||

|

|||

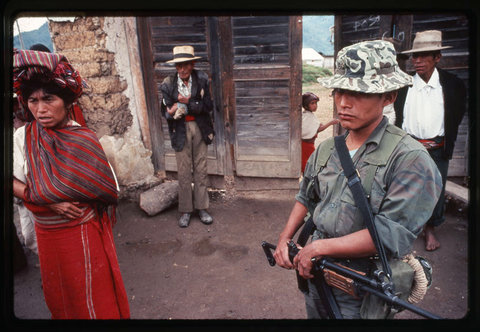

Jean-Marie Simon A soldier guarding captured peasants in a holding area near the army garrison in Nebaj.1982.

Jean-Marie Simon A soldier guarding captured peasants in a holding area near the army garrison in Nebaj.1982.