Peoples and Cultures of Early Sri Lanka

by Dr. Siva Thiagarajah, Tamil Information Centre, released March 31, 2012

|

The megalithic period also showed bones of birds, fish and animals including dogs and cattle suggesting they were domesticated. The large number of cattle bones implied its use for agricultural purposes. The presence of paddy husks indicated that rice was one of the cereals cultivated. Some bones of cattle showed clean-cut-ends using a sharp instrument indicating that they were consumed for food as well. Although no burials for this period has been identified at this site to-date, the presence of Black and Red Ware, iron, evidence of cultivation, and the presence of a large number of fields and tanks in this area taken together signify a prevailing Megalithic Culture (Sitrampalam, S.K. 1993: 11-13). |

TAMIL INFORMATION CENTRE

Seminar and Book Launch

PEOPLES AND CULTURES OF EARLY SRI LANKA:

A study based on Genetics and Archaeology

SOAS, Thornhaugh Street, London WC1H OXG

Saturday, 31 March 2012

PROGRAMME

12.25pm Registration

1.30pm Welcome

Mr Gurunathan, Director Tamil Information Centre

1.45pm Chair’s Introduction

Dr Dorian Fuller

2.05pm Book Launch: Peoples and Cultures of Early Sri Lanka

Professor John Carswell

2.20pm Book Review by Professor Suchartha Gamlath

(A DVD Presentation)

2.30pm Book Review by Dr Raveendran

2.50pm Book Review by Mr A Thevarajan

(A DVD Presentation)

3.00pm How important is this book? by Uvindu Kurukulasuriya

3.400pm Coffee Break

4.10pm Author’s commentary – Dr Siva Thiagarajah

4.25pm Discussion

Facilitator: Dr Dorian Fuller

5.30pm Close

SEMINAR CONTRIBUTORS

DR. DORIAN FULLER BA, MPhil, PhD, is a reader in Archaeobotany at the Institute of Archaeology, University College, London. He has been involved in prehistoric and proto-historic research in South India for several years. He is a joint director of the Bellary Archaeological Research Project and has produced a considerable number of research papers on the Archaeobotany of the South Indian Neolithic period. As a part of the Early Rice Project and Sealinks Project he has studied the Archaeobotany of Mantai, Sri Lanka, one of the earliest ports in South Asia.

PROFESSOR JOHN CARSWELL is a Visiting Professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He was the curator of the Oriental Institute Museum and Director of the University of Chicago’s Museum of Fine Arts for about ten years. As early as 1951 he was involved in the archaeological dig at Jericho by Kathleen Kenyon. Between 1980 and 1984 he headed the team from the University of Chicago which conducted archaeological excavations at Mantai in Sri Lanka. His new book on Mantai is due to be published shortly.

Mr. RAMA GURUNATHAN is a Director of the Tamil Information Centre (TIC) and a Member of the Executive Committee of the charity the Centre for Community Development. He has been involved in voluntary services in the areas affected by tsunami and worked with medical professionals assisting internally displaced people held in camps after the end of war in Sri Lanka. He also has authored two books, one in Tamil – a travelogue titled ‘From Istanbul to Cairo – An overland journey’, and another in English - ‘Temples of Tamil Nadu’.

Dr. M. RAVEENDRAN MBBS, MRCOG, MSc, is a Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist working for the NHS at the Newham University Hospital. He has a Masters degree in Genetics. He is an honorary senior lecturer at the Queen Mary University of London.

PROFESSOR SUCHARITA GAMLATH PhD is an experienced academic proficient in classical Indian languages and the Sinhala language. In 1975 he began working as a Professor of Sinhala language and literature at the Jaffna Campus of the University of Sri Lanka as well as Dean of the Faculty of Humanities. In 1977 he was appointed as the Vice Chancellor of the Colombo Unit of the Jaffna Campus. He became the Dean of the University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka in 1979. He is now retired.

DR. SIVA THIAGARAJAH BSc, MBBS, PhD, is now retired after working as a medical doctor for 40 years in Sri Lanka and in the UK. His long time interest in history and archaeology, and his specialised training in genetically inherited disorders have provided the background to produce this book. Apart from archaeological and historical research, he has researched the early religious history of South Asia to produce the work Tamils and their Religions. He also has produced a Tamil translation of the Sumerian epic, The Epic of Gilgamesh, discovered through archaeology.

MR. A.THEVARAJAN, a native of Jaffna in Sri Lanka was one of the first to study the Brahmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka and bringing the Tamil names and other Dravidian elements in them to the attention of scholars in India and Sri Lanka. During the early 1970s he was associated with the Jaffna Archaeological Society and brought to light a megalithic urn burial at Vallipuram. He migrated to New Zealand in 1997 where he founded the New Zealand Tamil Studies and Humanitarian Trust. He was honoured at the Queen Elizabeth II New Year’s awards in 2011 for his services to the community.

UVINDU KURUKULASURIYA is an award winning journalist and freedom of expression activist with more than twenty years experience. He won an award for investigative journalism from the Editors Guild Sri Lanka and became the finalist on two occasions for the South Asian Tolerance Prize, awarded by the International Federation of Journalists. He was also the Convenor of the Free Media Movement, Co- convenor of the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence, Director of the Sri Lanka Press Institute and the Press Complaints Commission Sri Lanka. He now lives in exile in the UK from where he acts as the Editor-in-Chief of the online Colombo Telegraph. He is also weekly columnist for the Sunday Leader, Colombo. He is a visiting fellow of London School of Economics and Political Science.

2010 article series from Sri Lanka Guardian

The people and cultures of prehistoric Sri Lanka

Part 1 ---

THE KANTARODAI PERIOD OF ANCIENT JAFFNA 1000 BCE – 500 CE

by Dr. Siva Thiagarajah

“It stands to reason that a country which is only thirty miles from India and which would have been seen by the Indian fishermen every morning as they sailed out to catch their fish would have been occupied by men who understood how to sail. I suggest that the North of Ceylon was a flourishing settlement centuries before Vijaya was born.” - Sir Paul E.Pieris, 1919

Nagadipa and the Buddhist Remains in Jaffna, Part II p।65.

KANTARODAI

“ Whether it is Podiyil, or whether it is Himalayas

The wise and the learned always stated

That Puhar is the port of illustrious people

Of splendour and grandeur like in heaven

Its riches, wealth and longevity

Rivalled that of Naka Nadu.”- Silappadikaram I:2.

(August 07, Colombo, Sri Lanka Guardian) The twin epics of ancient Tamil Nadu Silappadikaram (2nd century CE) and Manimekalai (3rd century CE) speaks of Naka Nadu across the sea, and their civilization which was far superior to that of the Cheras, the Cholas and the Pandyas. Manimekalai speaks of the great Naka king Valai Vanan who ruled the prosperous Naka Nadu with great splendour and a rich Tamil Buddhist tradition (Manimekalai Ch.14, 24).

Kantarodai has long been identified as the most ancient capital of Jaffna, when it was known as Naka Nadu or Nagadipa and ruled by the Naga kings. Several ancient coins unearthed in this region almost every year with Naga names and Naga emblems attests to this fact. During the monsoon rains such coins are simply washed out of the ground, to be picked by children and sold to the coin-collectors for their pocket money.

Some historians have identified the Naga stronghold of Nagadipa during the sixth century BCE Kannavaddhamana mentioned in the Mahavamsa (Mahavamsa Ch I:49) and the city Maninagadipa mentioned in some Sinhalese chronicles with the present Kantarodai (Godakumbura,C: 1968: 71). The Yalpana Vaipava Malai refers to Kathiramalai as an ancient kingdom in this region; and simply because no other ancient kingdom in this region has been identified, Kathiramalai is equated with Kantarodai. Kadurugoda is a direct Sinhala translation of Kathiramalai. These nomenclatures seem to be conjectures rather than evidence-based inferences. Kantarodai appears to be the conflation of an earlier name which is lost to us and yet to be identified. Until this happens, Kantarodai should be the proper name used to refer to this ancient capital.

THE KANTARODAI MEGALITHIC STUPA COMPLEX

The stupas seen above were reconstructed by the Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka over the original bases found at this site. These stupas built over burials demonstrate the integration of Buddhism with Megalithsm, which has been described as a hallmark of Dravidian Buddhism. Outside Andhra Pradesh in India, Kanterodai is perhaps the only site where such burials are seen.

The Mahavamsa also describes a conflict between two Naga kings Mahodhara and Chulodhara over a gem-set throne, and how Gautama Buddha during the sixth century BCE came over to settle the dispute and convert many of the Nagas to the Buddhist faith (Mahavamsa Ch I: ). Although the coming of the Buddha to Nagadipa could be a myth, the fact that this region was ruled by Naga kings could not be dismissed lightly.

Unfortunately, while the British academics and the Sri Lankan historians who followed them built up an Anuradhapura centred history for Sri Lanka from the Pali texts, the northern region of the country was totally neglected. After the country gained independence, ethnic passions clouded the judgment of even the foremost academics. For example, Senarat Paranavitana, the doyen of Sri Lankan historians who gave a list of Naga kings who ruled from Anuradhapura in his prestigious ‘History of Ceylon’ published by the University of Ceylon (Paranavitana, S. 1959), when it came to writing the history of Jaffna, dismissed the Nagas as non-human beings who could not have ruled a country (Paranavitana,S. 1961).

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF KANTARODAI

The village of Kantarodai in Jaffna, about 3.2 sq.km in extent is in itself an archaeological mound situated at a higher elevation than the surrounding areas, with a heavy concentration of artefacts. The most ancient city is identified as a 2m high mound in the middle of the village covering some 25 hectares. It is located in the belt of fertile paddy land and is near a major tank, the Kantarodai Kulam, of some 40 acres, and an ancient canal called Valukkai Aru which winds its way up to Kallundai near Navanturai, a port in the west coast of Jaffna.

This site was first surveyed and excavated by Sir Paul E. Pieris in 1918-1919. He obtained 35 punch-marked silver coins which he referred to as ‘puranas’ belonging to the time of Lord Buddha, 18 early copper coins either square or oblong in shape from the pre-Christian centuries, several Roman coins, Pandyan coins, copper ‘kohl’ sticks which he said were similar to those used by the Egyptians in 2000 B.C., and several other Buddhist artefacts of significance.(Pieris, Paul, E. 1917, 1919).

The Sri Lankan Department of Archaeology has been engaged in horizontal excavations during the 1960s without any stratification, and brought to light a cluster of Buddhist monuments. However the motives and the measures taken by the Department of Archaeology in excavating Kanterodai were neither scientific nor academic. They were interested only in highlighting the Buddhist monuments, reconstructing them and presenting it to the world as evidence of a Sinhalese settlement of Jaffna. But Kanterodai is far ancient, unique in significance and wider in perspective than conceived by the government department.

The first systematic excavation and scientific examination of the site was undertaken by the University of Pennsylvania Museum team in 1970 headed by Vimala Begley. A ceramic sequence remarkably similar to that of Arikamedu was identified, with a pre-rouletted ware period, subdivided into an earlier (1a). Megalithic, and later (1b).Pre-rouletted ware phase, followed by a (2). Rouletted ware period. In 1973, before the results of the Radio-carbon dates from this excavation were known Dr.Begley assigned a tentative date for the beginnings of the Megalithic Culture at Kantarodai to the fourth century BCE (Begley,V. 1973).

The Radio-carbon dates were released by the Pensylvannia University Museum in 1977, but it took another five years for the Archaeological Commissioner of Sri Lanka to obtain these results from Bennet Bronson who was a member of the excavation team. These results were first published in Sri Lanka in the Sun group newspaper ‘Weekend’ dated 8/2/1982. The dates provided were a revelation, as two out of a total of sixteen artefacts analysed gave outer dates of 1300 BCE, implying the possibility of a Megalithic Culture commencement at this site during the second millennium BCE.

Further surveys, surface explorations and an excavation at the adjacent site at Anaikoddai were conducted by the University of Jaffna team in 1980-81 (Ragupathy,P.,1987; Indrapala,K,, 2006: 337) and in 1994-1995 by Krishnarajah of the University of Jaffna (Krishnarajah,S.,1998, 2004).

CLASSIFICATION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDINGS

During the months of June–August 1970 excavations were conducted at Kantarodai by the University of Pennsylvania Museum team. Academic staff from the Department of History; University of Jaffna were part of this excavation group. Two trenches marked ‘A’ and ‘B’ were dug up to depth of 4m. at the Woodapple site not far from the Buddhist stupa complex. The artefacts collected were analysed and some of them were taken to U.S.A for radiometric analysis. Unfortunately the official report of this excavation was never published. Dr. Indrapala and Dr. Sitrampalam from the University of Jaffna team who were present at these excavations were able to record some of their observations during this excavation in their own publications. (Indrapala,K 1973: 18-19; Sitrampalam,S.K. 1993: 11-13).

During 1980-81 Dr. Ragupathy from the University of Jaffna was able to collect some artefacts and record his observations while a well was dug up at Kantarodai, which appeared in his comprehensive dissertation ‘Early settlements in Jaffna’. During 1994-1995 Krishnarajah and his team from the University of Jaffna, after obtaining permission from the Sri Lanka Archaeological Department conducted surveys and excavations at this site (Krishnarajah, S., 1998, 2004). These findings are also utilised here to complement the picture.

During the excavations, the deepest layer of human occupation was identified as the Megalithic, hence I have classed it as Period I. Although Allchin mentions of finding microliths at a site near Jaffna under four feet of earth (Allchin, B.&R. 1993: 96), presence of microliths were not reported at Kanterodai. Evidence of occupation by a prehistoric Mesolithic people in the Jaffna peninsula has not come to light in these excavations to-date. Perhaps future excavations may change this picture, in which case this classification has to be revised.

Part 2 ------

PERIOD I: Megalithic Period : 1300-300 BCE

(August 11, Colombo, Sri Lanka Guardian)The Megalithic Period is datable between c.1300-130 BCE, and included finds of Black and Red Ware and other types of pottery, copper, bronze and iron. Earthenware Pots and pans were used in every day life, and the variations and the changes in shape, form, texture and format over the years is an indication of a peoples’ cultural progression. Because of the presence of undeciphered graffiti in the potsherds, some investigators assign this to a proto-historic period.

The Pennsylvania team has classified the pottery into three types. Type A pottery – the Early Red Ware, had smooth rims of a reddish colour (Roman red). Type B are the traditional Black and Red ware associated with the Megalithic Culture, similar to Mortimer Wheeler’s finds at Brahmagiri and Arikamedu. Type C were thick rimmed, thick bodied and shaped like large jars. These were smooth and devoid of any decorative patterns. The Early Red Ware as well as Black and Red Ware had graffiti marks on their necks (Orton,N. 1995). The structural form of the pottery and the nature of graffiti, a characteristic of the Megalithic Culture, closely resemble the pottery structure and its graffiti from Anuradhapura, Pomparippu, Divulwewa, and Makevitta (Sitrampalam, S.K. 1993:12).

Commenting on the Black and Red Ware, Vimala Begley stated that these resemble the pottery of South Indian Iron Age, and the people of Kantarodai have either descended from the same cultural milieu as the South Indians or had very close cultural contacts with them (Begley,V। 1973).

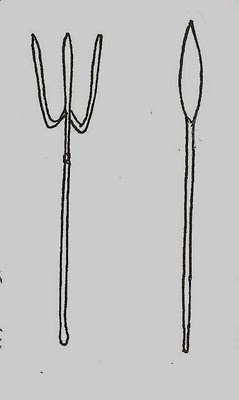

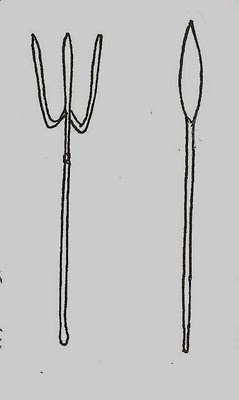

MEGALITHIC BRASS ARTEFACTS OF RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE.

Early forms of iron nails and iron tools, as well as some copper and brass tools were found in this layer. Most notable among the brass artefacts were tridents, and a lance (Vel) with its head shaped like a leaf. Such artefacts are commonly found among the Megalithic burials of South India and indicate Megalithic religious practices, the fore-runner to latter-day Saivism. There were also kohl sticks made of brass as well as copper. It is of note that one of the Kohl sticks had the impression of a rice husk. (Sitrampalam, S.K. 1993: 11-12). It may be that rice husks were used as fuel during the smelting of copper.

The megalithic period also showed bones of birds, fish and animals including dogs and cattle suggesting they were domesticated. The large number of cattle bones implied its use for agricultural purposes. The presence of paddy husks indicated that rice was one of the cereals cultivated. Some bones of cattle showed clean-cut-ends using a sharp instrument indicating that they were consumed for food as well. Although no burials for this period has been identified at this site to-date, the presence of Black and Red Ware, iron, evidence of cultivation, and the presence of a large number of fields and tanks in this area taken together signify a prevailing Megalithic Culture (Sitrampalam, S.K. 1993: 11-13).

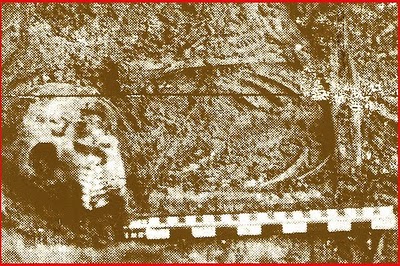

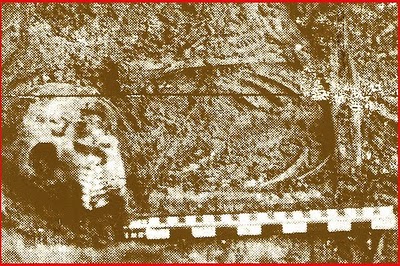

Anaikoddai is an important area near Kantarodai, where the prehistoric site covers an area of more than two square kilometres. The actual Megalithic burial mound occupies an area of two acres in the paddy field stretch at Anaikoddai. Earth scooped out from about half of this mound was used to fill a low lying land for the Navanturai housing scheme; the other half remains undisturbed. The state did not bother to protect this area.

Explorations of the mound showed evidence of a Megalithic Culture Complex with extended and urn burials associated with a large number of Early Carinated Black and Red Ware and iron artefacts. Near an urn a copper kohl stick was found. Conch-shells, crab-shells, animal bones, and heaps of grooved tiles were found in the vicinity. A Rouletted Ware sherd had two evolved Brahmi scripts stamped on it. The other surface finds included a number of iron slags, tools, oystershells, bones, polished and unpolished vertebra bones, fish bones and rubbing stones (Ragupathy, P. 1987: 66-67; Indrapala, K. 2006: 86)

A MEGALITHIC BURIAL AT ANAIKODDAI. COURTESY: DR.P.RAGUPATHY

Part 3 -------

PERIOD II: Early Historic Period 1: 300-200 BCE.

(August 21, Colombo, Sri Lanka Guardian) The Early Historic period is marked by the appearance of an epigraph with decipherable script indicating the presence of a ruler or chieftain. Pottery continues to be of the Black and Red Ware as well as the Early Red ware types. Brahmi alphabets are making their appearance in potsherds, the most commonly found symbol being the Tamil Brahmi letter ‘ma’.

There were also various kinds of beads made of glass, ivory, chank, carnelian and marble. These were blue, dark blue, green, light yellow and white in colour. Beads were found in all the layers, being most abundant in the superficial layer. In1919 Sir Paul Pieris collected more than 26,000 beads and a variety of copper Kohl sticks from this site.

Baked bricks were making their appearance at this level, as well as post holes for the erection of pillars or posts for the building of houses. There were also grinding stones, as well as rolling pestles made of stone and smoothened on the surfaces. An interesting find was a carnelian stone showing the picture of a chariot and driver (Sitrampalam,S.K. 1993: 11) believed to be of Roman origin.

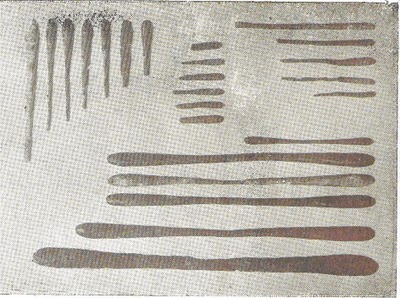

COPPER KOHL STICKS FROM KANTARODAI, 1918. COURTESY: PAUL E.PIERIS.

There were early Pandyan coins, as well as Indian punch marked coins which Paul Pieris dated to 500 BCE (time of Buddha), suggesting maritime trade relations with India were under way during this period. It was on the strength of this finding Sir Paul Pieris wrote: It stands to reason that a country which is only thirty miles from India and which would have been seen by the Indian fishermen every morning as they sailed to catch their fish would have been occupied as soon as the continent was peopled by men who understood how to sail. I suggest that the North of Ceylon was a flourishing settlement centuries before Vijaya was born (Paul E.Pieris 1917, 1919: 65).

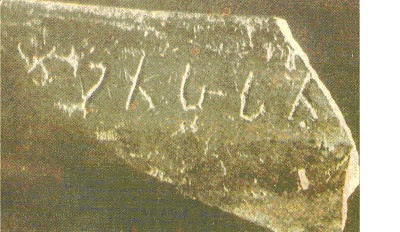

KANTERODAI SCRIPTS

During the excavations conducted for the University of Jaffna by S.Krishnarajah and his team in 1995 at Ucchapanai in Kanterodai several BRW potsherds with Brahmi writing were brought to light. Three of these potsherds had complete legends written in Tamil Brahmi datable to 300-200 BCE (Krishnarjah, S. 2004).

The three legends are as follows:

1. Chadarasan: This resembles the legend Chadanakarasan found in a coin discovered at Akurugoda by Osmund Bopearachchi and colleagues, which related to a Naga king.

2. Apisithan: The term ‘Api/Abi’ is usually taken as the female form of ‘Ay’. Here, as the word ends in –an, it is taken for a male. In Indian literature Abiram and Abimanyu were names given to heroes.

3. Palur: In Tamil literary sources ‘Palur’ is the name given for Dandapura in Kalinga. Ptolemy too mentions Balur as a port in Kalinga. This may indicate the trade relations Kantarodai had with Kalinga.

ESTAMPAGE FROM POTSHERD WITH LEGEND PALUR IN TAMIL BRAHMI CHARACTERS. COURTESY: S.KRISHNARAJAH.

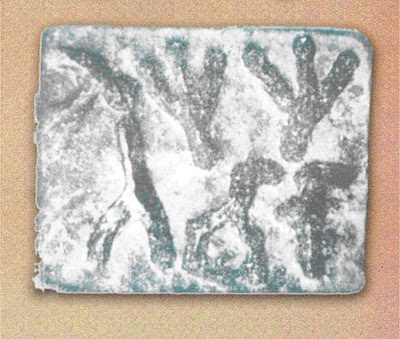

A stealite seal inscription was among the artefacts excavated at Anaikoddai by the University of Jaffna team in December 1980. The legend on the seal has two lines. The first line consists of three non-Brahmi symbols. The second line has three Brahmi letters and read as Koveta. The name Koveta is not Prakrit. It is comparable to the names KoAtan and KoPutivira occurring in the contemporary Tamil Brahmi inscriptions of South India. The script is taken as Early Tamil similar to the South Indian inscriptions of 300 BCE.

Ko in Tamil and Malayalam means ‘king’ and no doubt refers to a chieftain here. (Indrapala,K. 2006: 337). The first line of non-Brahmi letters may represent royalty or a form of early writing known to these people.

The Anaikoddai seal and Kanterodai potsherd scripts helps to establish two significant facts: (1): By 300 BCE there was a king or chieftain Ko Veta, was ruling this region. The name Chadarasan too may refer to a king. (2). Tamil language and Tamil Brahmi writing was known to the people of this region during this period.

THE ANAIKODDAI SEAL. THE SYMBOLS ON TOP MAY DENOTE ROYALTY OR MAY BE A PREVIOUS SYSTEM OF WRITING. THE BOTTOM LINE IN TAMIL BRAHMI CHARACTERS READS KO VETA.

PERIOD III: Early Historic Period 2: 200 – 10 BCE (Rouletted ware Period)

The succeeding period dated between c.200-10 BCE, yielded in addition to the BRW and fine grey wares, rouletted ware, Arikamedu type pottery, Eastern Hellenistic wares, semi-precious bead stones and Laksmi plaques. This period appears to be contemporary with the adjacent Buddhist complex of Kantarodai.

A rouletted ware potsherd with Brahmi inscription was discovered in this layer. This find was given the number KTD A14. Dr.Indrapala opined that the potsherd presumably formed part of the begging bowl of a mendicant monk. The reading is Dataha pata. The language is the same as the pre-Christian Prakrit Inscriptions of Sri Lanka. Dataha pata means the bowl of Datta. The Prakrit script is dated to the second centuty BCE (Indrapala,K. 1973: 18-19).

A ROULETTED WARE POTSHERD WITH BRAHMI SCRIPT IN PRAKRIT DATAHA PATA

There is nothing in the above script to suggest that Datta was the name of a monk. It is incorrect to assume that all pottery found with names were begging bowls of monks. In the past the traders, the owners, the makers and every ordinary person had the habit of incising their name on the pottery. As the name suggests, Datta was probably a person of the merchant class from Bengal. In several stanzas Manimekalai mentions a merchant-trader from Vanga called Chandra Datta who frequently visited Naka Nadu (Manimekalai Ch.XVI); Datta seems to be a common name among the Bengal merchants.

Details of coins recovered in the 1970 excavations have not been fully published, but they include silver and copper punchmarked coins, Buddhist chakrams, coins with elephant and swastika emblems, Roman coins, maneless lion and Laksmi plaques (Orton, N. 1993). The large amount of Roman coins from this period obtained by Paul Pieris in 1917-18, and by the Pennsylvania team in 1970; as well as the presence of rouletted ware and Roman artefacts indicate that there was an established Roman trade by this time. South Indian Pandyan coins and the Buddhist chakrams suggest an active trade with South India from 300 BCE. The carnelian stone depicting a chariot and driver mentioned under Period II, is presumed to be of Roman origin.

PERIOD IV: Historic Period 1: 10 BCE – 500 CE

This is the period of an established Naga kingdom, when Naka Nadu became a rich nation with a ruling dynasty, its control extending up to Mantai in the North-East, Gokarnam in the North-west and Mahavillachi in the middle. The socio-economic structure of this nation was built around its oceanic trade and agriculture, the trade with Rome being the mainstay of its economy.

There is a reference to Naka Nakar in the early Brahmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka (Epigaphia Zeylanica VII, No. 82) belonging to 200 BCE, which is believed to be denoting Kanterodai. An early copper coin discovered at Uduththurai carries the name Nakabumi in Tamil, referring to the Naka Dynasty of the North (Pushparatnam, P. 2002: 11, 30). Ptolemy in his first century map of Taprobane also mentions Nagadiboi.

The urbanization of Kantarodai paralleled that of Anuradhapura and Mahagama. But while Anuradhapura and Mahagama were essentially Hydraulic Civilizations relying on agriculture to produce surplus wealth, Kantarodai relied heavily on its trade. Two reasons could be attributed to the decline of this civilization. (1). By the fifth century Anuradhapura became a powerful kingdom and took over the port of Mantai which was generating tremendous wealth. The expanding Chinese and Arabian trade was by-passing Jaffna and concentrating on Mantai, (2).The Roman empire was disintegrating and the decline of the Roman trade in the fifth century rang the death-knoll of this civilization. However Kanterodai continued to be a capital in Jaffna until it was replaced by Singai Nakar during the ninth century, thereafter remaining as a modest village.

The mature historic phase of this civilization is outside the scope of this work; hence only a brief outline is given here. Its origins and evolution as a powerful force in this region, which determined its future history is briefly discussed below.

Part 4 ------

THE KANTARODAI CIVILIZATION

Previous Parts: Part One | Part Two | Part Three

by Dr. Siva Thiagarajah

EARLY SETTLEMENTS AROUND THE JAFFNA LAGOON

(August 23, Colombo, Sri Lanka Guardian) In their archaeological surveys of the Northern province of Ceylon, J.P.Lewis in 1916 and Paul E. Pieris in 1917-1919 identified Kantarodai and Vallipuram in Jaffna as two pre-historic sites. In a major archaeological survey of the entire Jaffna peninsula undertaken during the years 1980-1983, Dr.Ragupathy of the University of Jaffna has identified three sites namely Kantarodai, Anaikoddai and Karainagar which showed evidence of a Megalithic Culture; and three more sites Vallipuram, Velanai and Mannithalai an early historic phase of settled civilized life. In 1993 Dr. Pushparatnam, also from the University of Jaffna added Poonakari as the seventh early historic site to the above list. Among these settlements Kanterodai emerged as the centre of political, religious and cultural power, while the others remained as satellite settlements with strong links to the centre.

As evidence of a Mesolithic population occupying the Jaffna peninsula has not come to light, it is assumed that the Megalithic people were the first humans to arrive in this region. They could have either migrated from South India or from the North-west of Sri Lanka which had a Megalithic population from the second millennium BCE. It is of significance to note that all the early settlements were dispersed around the Jaffna lagoon, suggesting the oceanic origins of this culture, and how the sea played a dominant role in sustaining and developing these settlements.

During later times, the medieval city of Jaffna too emerged at this site because of its strategic location along the Jaffna lagoon. It could be approached through the lagoon sea routes from the north, south and west; and boasts no less than three ancient ports Pannaiturai, Kolumputturai and Navanturai.

ECONOMY: TRANS OCEANIC TRADE AND AGRICULTURE

The satellite settlements were self-sufficient communities with multi faceted subsistence patterns. A combination of farming, pasturing and lagoon fishing provided the basic subsistence of this population. But, it was the Maritime Mercantile Culture that laid the foundations for the advancement of this civilization. Because of its geographic location and the prevailing conditions of that period, Jaffna was able to participate actively in the transoceanic Roman trade and in the trade between India and Sri Lanka. During the early periods trade was the basis of the development of the socio-economic structure of Jaffna.

An active maritime trade between Sri Lanka and India was present during the first millennium BCE, and the trans-oceanic trade between Rome and South Asia emerged just before the Common Era. The early trade routes were mostly coastal passages. These ancient small Arabian and Roman vessels coming from the Arabian Sea towards the Bay of Bengal, went through the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait to reach the east coast of India and East Asia. The strategic location of Jaffna in this trade network was a significant factor in its emergence as a city state in early times.

Four major ports- Jambukolam and Kayaturai (Kanterodai), Navanturai (Anaikoddai) and Pallavaturai (Vallipuram) during early historic times provided the impetus for the establishment of a trans-oceanic trade. Apart from Jambukolam and Kayaturai, Navanturai too acted as a port of the capital. Some believe that Valukkai aru was a sea-canal which ran from Navanturai to Kantarodai and beyond; and this acted as a passage to carry small boats from the harbour to the capital, but realistically this appears to be a major flood outlet.

After the fifth century BCE, the Roman trade gave way to the Arab-Chinese trade shared by the Pallavas, Cholas, Pandyas and the Sinhalese. With the advent of larger ships and new steamers, the Palk Strait Passage was abandoned and these ships started circumnavigating Sri Lanka in their new passage. Colombo and Galle became major harbours of this new trade route, and as a result the importance of Jaffna in this later trans-oceanic trade diminished.

WATER SOURCES AND SUSISTENCE PATTERNS

Except for a few tanks, notably the Kantarodai kulam and Nandavil kulam the Jaffna peninsula has no rivers or reservoirs. The entire peninsula rests on a bed of limestone and the limestone ground water is the main source of fresh water. To obtain this water the limestone bed has to be dug up to a depth of 20-30 feet. But in the limestone terrain there are naturally formed sink water holes, tidal wells and springs that may have been used by the early settlers. Apart from this dune-sand ground water and coral layer groundwater forms the sources of fresh water.

In Jaffna, while a portion of the rainwater percolates to the limestone rocks, the remaining surface run-off flows towards the lagoon of the peninsula. As the coast facing the deep sea is higher in elevation than the lagoon coast, most of the flood outlets flow towards the lagoon. This process almost submerges the coastal alkaline plains for 2-3 months, and would have provided ideal paddy fields for the early subsistence farmers (Ragupathy, P. 1987: 140-141).

Paddy cultivation in the alkaline stretch along the lagoon coast happened only once a year, during the returning monsoon rains. Almost all the early sites located in the peninsula had a stretch of paddy-field hinterland. After the harvest in January, leguminous plants, sesame, ragi, melons and vegetables were cultivated. They would be ready for harvest before their traditional new year in April. The capital Kantarodai had a major tank, and it remains one of the primary centres of rice irrigation in the peninsula to this day.

The beginnings of cattle and sheep breeding could be dated to the times of early settlers as cattle and sheep bones and teeth remnants were found in the stratified layers along with the Megalithic pottery. Primitive type of goat and sheep breeding could be still noticed at Parutitivu, a small island off the coast. The Jaffna lagoon also offered easy access to sea-food. The presence of shark vertebrae, other fish bones, crab shells, turtle shells, oyster shells, conch shells, and snail shells were seen in plenty in the Megalithic burials ( Ragupathy, P. 1987: 144, 164).

IRON TECHNOLOGY

Smelting/melting of iron was evident right from the Megalithic times as testified by the presence of a large number of iron slags found at the sites and in the excavation trenches. The local iron-containing laterite found in the Peninsula and in the Vanni region could have been used as the raw material. The early settlers could have evolved a primitive technology to extract iron from this raw materal, which may not be commercially profitable in modern times. A.Mootathamby Pillai (History of Jaffna, 1912: 105) refers to Ilam Iron, the indigenous production of iron in Jaffna (Ragupathy,P. 1987: 165).

TRAVEL AND TRANSIT

The mode of travel was through Sea-routes, Lagoon routes and by Overland routes. Jambukolam (Jambukola), identified with the present Sambuturai, as well as Kayaturai catered to the needs of the capital Kantarodai. Apart from the trade carried out through these ports, they remained important ports of embarkation for passengers and pilgrims to India. It was through the Jambukolam port that Buddhism arrived in Sri Lanka, and Kayaturai (later Kankesanturai) was so named because it was a port of embarkation for pilgrims to Buddha Gaya.

The Jaffna lagoon had two northern entrances one between the island of Karainagar and Ponnalai which is now blocked by a causeway, and another between Karainagar and Kayts. Ships were able to enter the Jaffna lagoon to reach Navanturai from the north as well as the south. Small ships and boats would have been plying regularly between the peninsula and the islands.

There were ancient trunk roads and smaller cart-tracts connecting the villages, which were tarred up in recent times. The explorations and excavations conducted by Dr. Ragupathy indicate that an ancient trunk road connected Valikamam with the sand bar settlements of Vallipuram. The remnants of wayside madams situated along the highways served as rest houses for pedestrians, carts and caravans.

|

Home

Home Archives

Archives